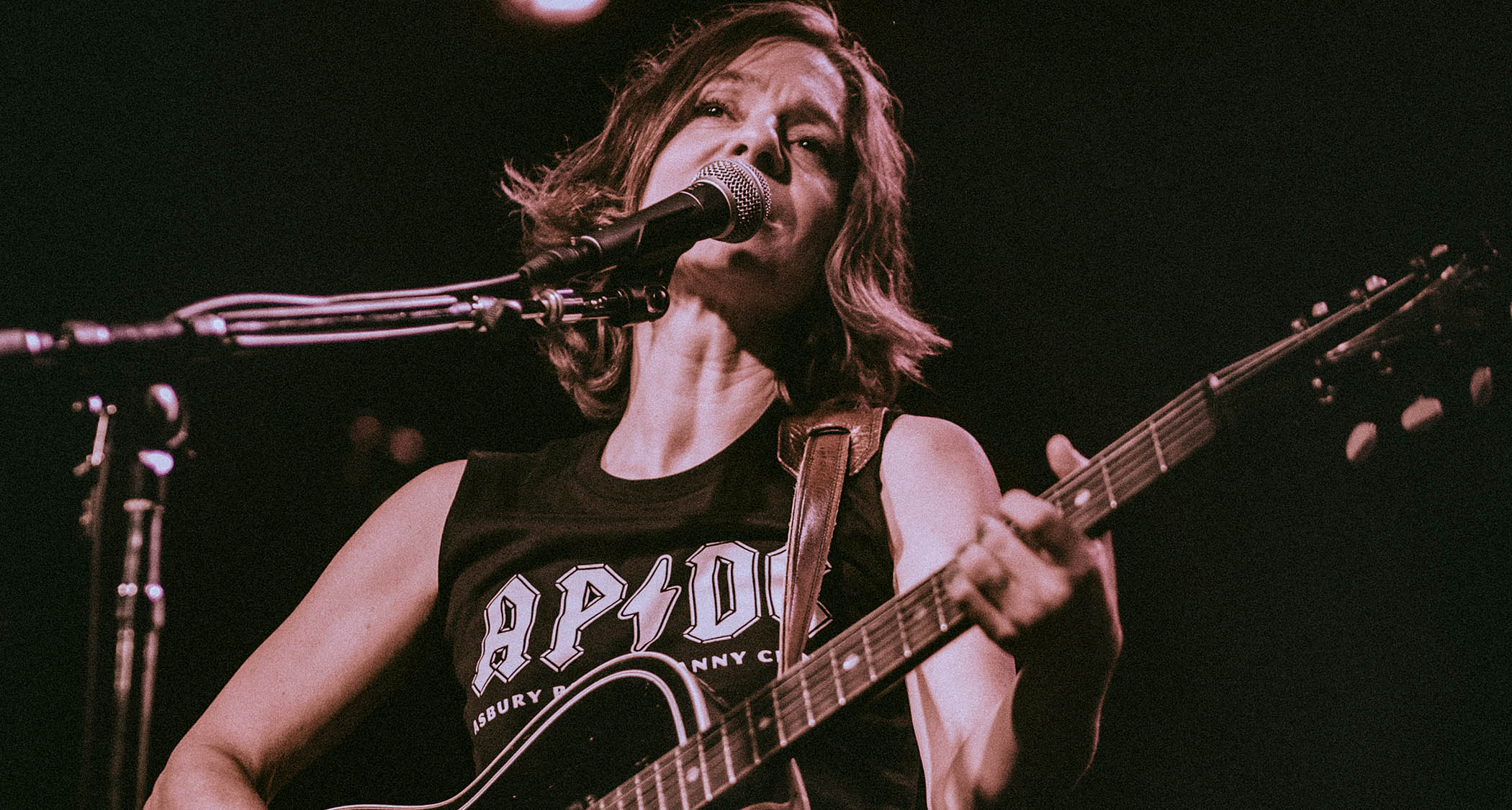

“I developed my playing style from being in bars, playing solo. People are shouting over your music... silences make them notice themselves – and then they notice you”: Ani DiFranco on the dark arts of acoustic – and why she’s over online ‘performers’

Percussive and heavily processed, the US troubadour’s new album, Unprecedented Sh!t, burns the playbook of acoustic folk

By her own description, Ani DiFranco set out on her career in the early ’80s as “this little chick in the corner with an acoustic guitar, trying to get the attention of people who were not naturally predisposed to pay attention to her little heartfelt numbers”.

Four decades later, in almost every respect, the 53-year-old New Yorker is unrecognisable. Since finding major-league success with mid-90s albums such as Dilate, DiFranco has commanded a global fanbase who hang on every socially charged lyric.

And while the acoustic is still this alt-folkie’s instrument of choice – and her rippling, percussive fingerstyle remains a potent weapon – latest album, Unprecedented Sh!t, finds those wood-and-wire tones cloaked in studio trickery by producer BJ Burton.

Your partnership with BJ Burton seems to have led your music – and guitar sound – in a radically new direction.

“For a long time, I’ve been wanting to harness the power of machines, in a way that I haven’t been able to on record, because I’m always just recording and mixing and producing my own shit. So I asked my management, ‘Who out there is young and knowledgeable about what the gear is and how to do something more than just set up microphones in front of my band and document what we do live?’”

“My managers sorta sniffed around and made a list of 20 names, and BJ Burton – I guess because his name starts with ‘B’ – was top of the list. And I looked at his album credits, which include Bon Iver and Low, and these things that were exactly what I’m talking about when I put out into the ether that I wanted to employ the world of machines, not just musicians playing instruments. So I didn’t even read any further, I just called BJ and he said, ‘Yes, send me some shit.’

“So that’s how we did it. We were barely in the same room together. We did it all at a distance. I would record the songs and send them to him and he’d mess with them. We were really in our own little worlds, just lobbing shit at each other.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

How did it feel to hand over an element of control after so many years as a self-reliant artist?

“Creatively, it was awesome to have BJ, and his incredible mastery of the world of gizmos, come in and realise exactly what I had hoped for – y’know, soundscapes that are a little more vast and varied than conventional instruments.

“It was hard for me in terms of waiting on him. I could put the songs down myself as fast and furious as I wanted, but then I would send them to him and just be in limbo. The process did kind of drag on for a long time because he’s busy and he would disappear for weeks and months at a time.

“So that took patience on my part to just say, ‘This is what I signed up for, this is gonna be worth it, I have to have faith.’ But yeah, it was frustrating to not be able to drive at whatever speed I was feeling.”

There’s a real contrast between the intimacy, simplicity and expansiveness on this new album. Was that by design or something that emerged?

“Well, I love contrast. From the beginning of making songs and playing them for people, it was all about that hairline between a whisper and a scream. I love to live right there. And BJ is just the same way. We really relate to each other in that.

“At one point, he was teasing me about something I was doing in one of the songs, and he was like, ‘What, are you trying to scare people?’ I knew what that joke meant – it’s because we both like scaring people. It was the pot calling the kettle black. We both like to be surprised and put out of the conventional or comfort zone with art.”

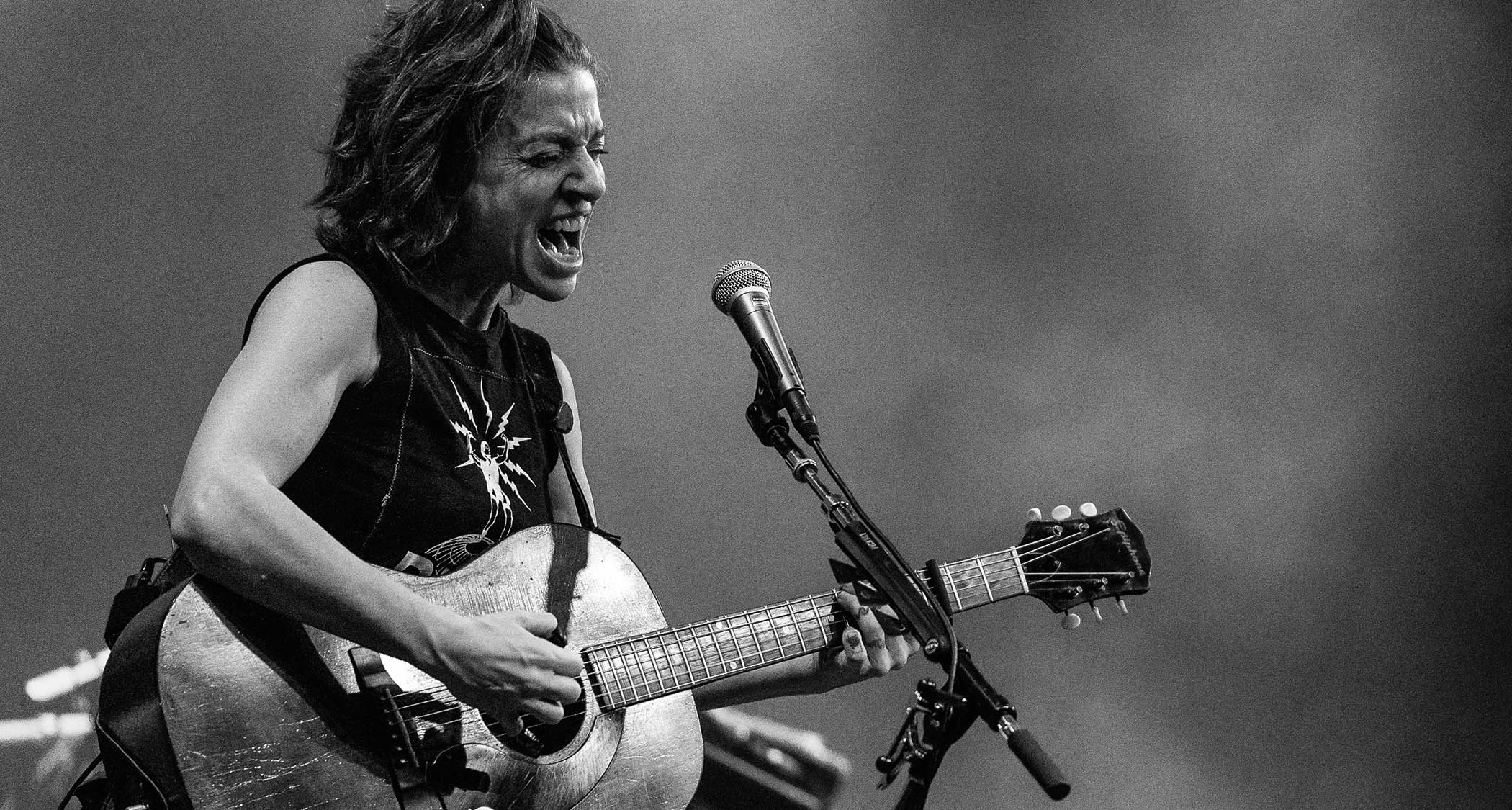

The rhythm of your right hand is so important for driving these songs. Where did that percussive style come from?

“I developed my playing style from being in bars and public spaces from the time I was a teenager, playing solo. It was all about leaning into dynamics and turning the guitar into a band with those percussive elements that I work with. And I learned very early on, if you play really loud – then stop suddenly – everybody’s words are hanging in the air.

“They’re shouting over your music and that makes them notice themselves and then they notice you – and then you have an opportunity to actually get their attention. And those were all devices that I learnt from playing live.”

Silence can be a really powerful dynamic.

`“Yeah, totally, and that’s why I am mostly a fingerpicker, not a strummer. Because strumming sort of erases all those silences, and fingerpicking is about making patterns out of silence. And I love it.”

What guitars do you find yourself gravitating towards today?

“I’ve grown up to be a Gibson girl. I mean, for many of my early years I played Alvarez because they were good workhorses on the road, and they were very kind to me as a company and would give me guitars. I still have some Alvarez guitars I employ, but my fella at some point was like, ‘You should play better instruments.’

“I should maybe not say that in public. Thank you, Alvarez. I love you, Alvarez. But he told me, ‘You should explore the world of vintage instruments.’ So I went to stores and played all the guitars from the ’50s and ’60s, and I found my ear favoured Gibson. So my workhorses now are, like, LG-1 type Gibsons. I also play four-string tenor guitars. Like, the song Baby Roe is a tenor guitar.”

What do you like about tenor guitars?

“My general game with an acoustic guitar is to crank the low-end. Especially when I’m playing solo. I have to move over and make room for a bass player and a drummer when I’m with the band, but generally I like a real beefy sound and I roll off the top of the acoustic kinda radically compared with how many people approach it and the place they put it in the mix.

My general game with an acoustic guitar is to crank the low-end. Especially when I’m playing solo

“But with a tenor guitar, it’s not really about that bottom. It sorta slots into the middle of the mix – it has this middy, midrange sorta sound. I don’t know, I think it’s cool how much room it leaves, for a change. And it makes me do different things, play differently. There’s also a song on this record called New Bible that I play ukulele on. It’s the only ukulele song I ever wrote.”

What you’ve done on this new record with Burton really goes against the grain. So many artists are so reverential about the sound of the acoustic guitar.

“BJ was absolutely non-reverential. On a lot of songs that have more expansive production, he turned my guitar into so many different sounds, and he built that out of just my voice and guitar. I was talking to somebody recently and they were saying how the record opens with this very meditative, murky keyboard part on Spinning Room, and I was thinking, ‘Yeah, that’s my guitar.’ BJ would just do whatever the hell to it.”

There’s a song called The Knowing where the guitar sounds really pitched down.

“The Knowing is a regular acoustic guitar and BJ just messed with it. That song is an interesting example because I released a version of it prior to this record coming out. I made a children’s book called The Knowing – so a version of the song that I made and mixed already came out with the book.

“So for anyone curious to discern the BJ effect, probably somewhere on the internet is the version of The Knowing that entered the world before this record. And then BJ got his hands on it and it has that really soupy, pitched-down, almost dissonant sound now.”

What are your intentions for performing Unprecedented Sh!t live?

“I don’t know. I’ve been in New York for six months doing a Broadway show [Hadestown], so I’m going to go home in the fall and revisit my life. So I won’t go out touring behind this record until the New Year. And how are we going to do it? How are we going to bring these songs to life on stage? I don’t know. I’m gonna see how that unfolds.

“I think this will be a little bit different in that I haven’t played with my band in a long time. We’re going to get together and rehearse these new songs from an album that has certain vibes and sounds going on – and I guess just see what happens, how we want to incorporate all that into how we’re gonna present these songs live.”

Before the internet, artists like Neil Young would put forward a viewpoint about the world and hoped it would change things. Now, we shout our opinions at each other on social media. Where do you feel that leaves the role of the songwriter?

“I’m not really a critic or a social theorist. I see my role as a songwriter as a type of storytelling. Songs don’t need to be direct instructions or lessons to change people or awaken something inside them.

“I try not to be too calculating or strategic about what effect I’m trying to have on the listener because that seems one or two steps removed from what I think my purpose should be, which is to just free myself and heal myself by getting the thing out of me.”

“And then, whatever somebody makes of it, or doesn’t, or if it helps them or bores them or whatever, that’s not my problem. And that shouldn’t be my focus, I think. So I think in that sense, the role of the songwriter is the same as it’s always been, which is to do something necessary for their own wellbeing and evolution and healing and liberation. And if people get off on that and they go with you, that’s awesome. And if not, keep doing it anyway.

“What I’m so over is people doing things for an effect. I’m so over people performing something for the world. On the internet, everybody is just creating these elaborate identities and performing them all day long.

“The focus is so much on, ‘How am I seen? I want you to see me in a certain way.’ I want to escape from that as much as I can. I don’t care how you see me. That’s not what it’s about.”

- Unprecedented Sh!t is out now on Righteous Babe.

Henry Yates is a freelance journalist who has written about music for titles including The Guardian, Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a talking head on Times Radio and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl and many more. As a guitarist with three decades' experience, he mostly plays a Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul.