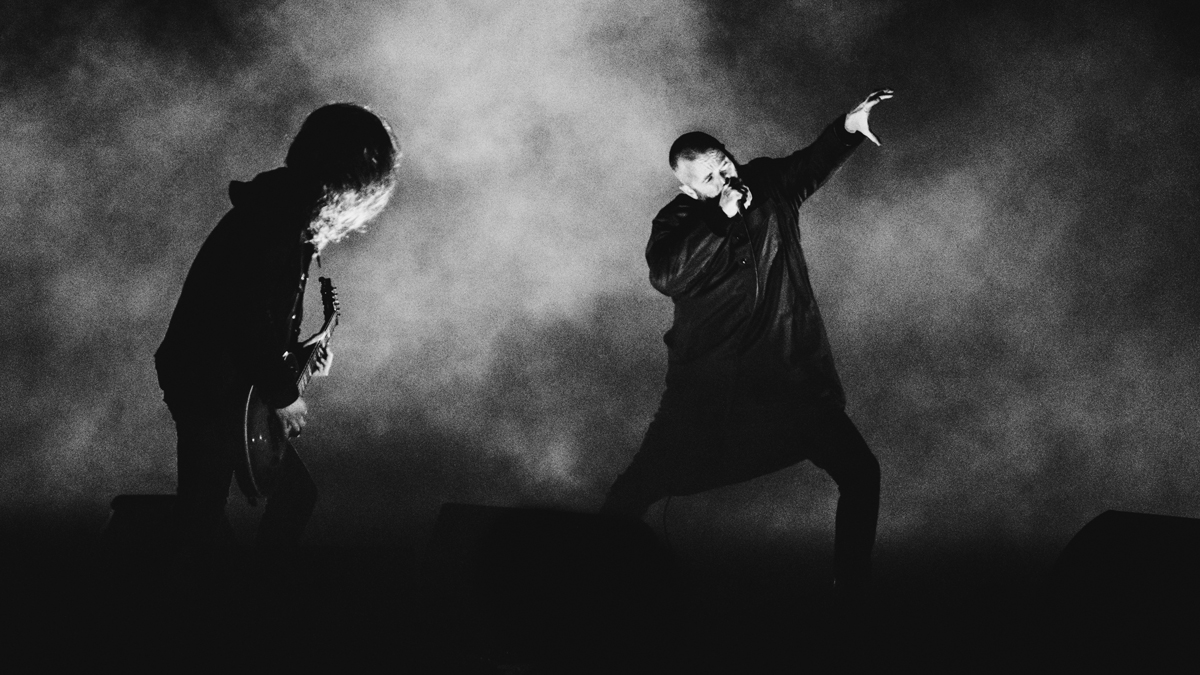

Amenra: “We try to limit how much we play. That's the essence of the band: when you’re playing the right notes, your impact is bigger”

Lennart Bossu and Mathieu Vandekerckhove on the playing and philosophy behind new album De Doorn, and what it's like to perform post-metal at a fire ritual

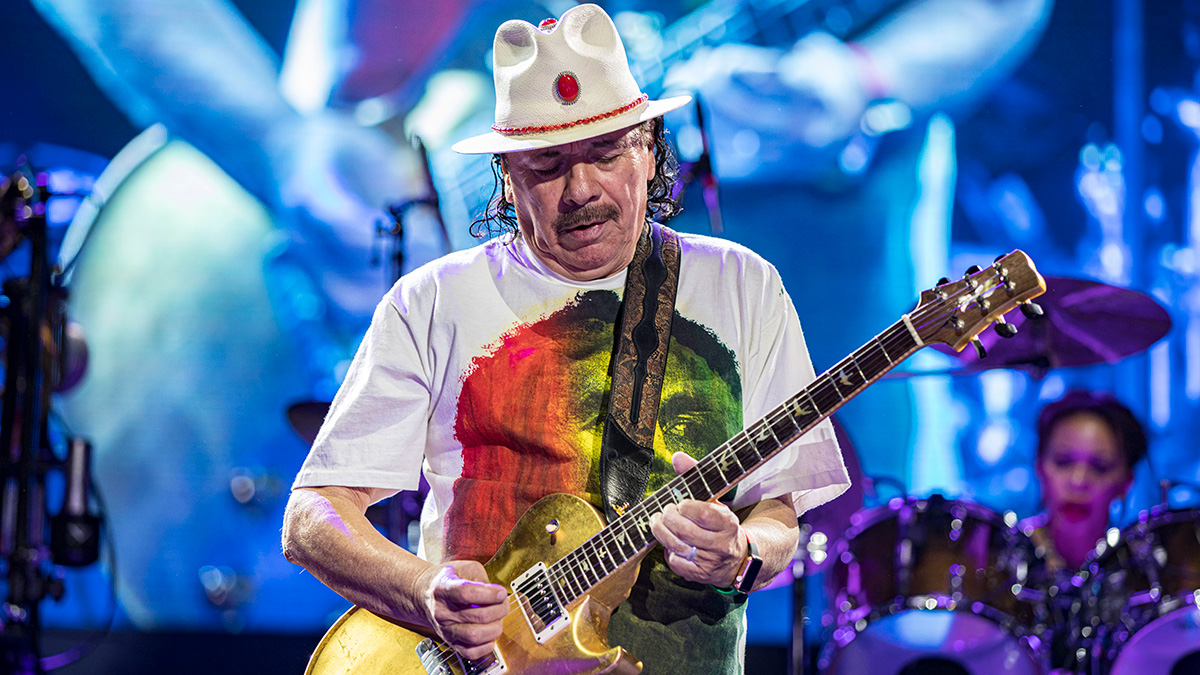

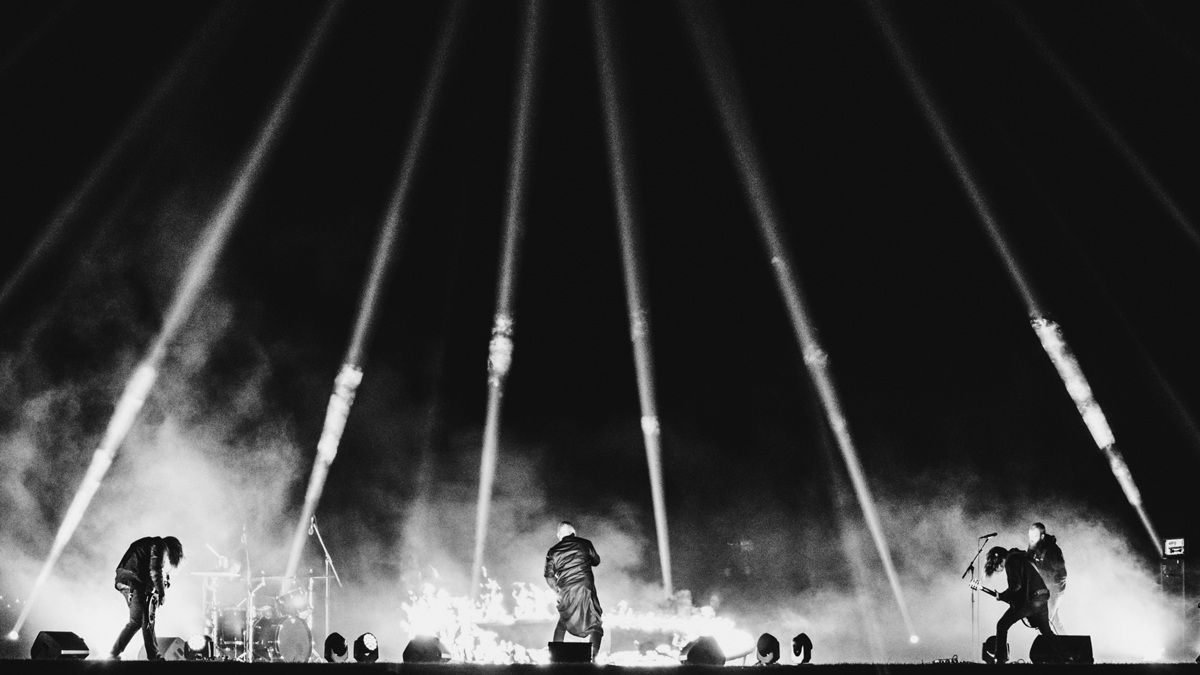

Belgian post-metal veterans Amenra fan the flames of inspiration with their latest release, De Doorn. Fittingly, the music had actually been written specifically for a pair of traditional fire rituals in their home country, with the band premiering these extended blazes of melancholy distortion in front of towering structures – one wooden, one bronze – that would be enshrouded by flame as each night went on.

“It was a special experience, being there and feeling the heat from the flames as you’re performing,” guitarist Lennart Bossu explains. “I guess we weren’t so much anticipating that while writing the songs, but it definitely intensified the performances.”

Though De Doorn continues Amenra’s melding of hardcore and gloom, it’s likewise a new chapter for the act. While the group’s long-running series of Mass albums were inward examinations of grief, De Doorn breaks from the mould as a more outwardly collective experience.

The fire rituals themselves, for instance, were a way for people to ceremoniously “burn their unacknowledged loss” while communing with Amenra’s music; the album grows the Amenra family as well, with guest vocalist Caro Tanghe – who Bossu also performs with in post-hardcore outfit Oathbreaker – providing cathartic cries throughout the release alongside primary vocalist Colin H. Van Eeckhout.

Across De Doorn, Bossu and co-guitarist Mathieu Vandekerckhove crest from simple, yet searing power chord damage (Ogentroost), towards elegiac tremolo-picking (Het Gloren), and smoldering, effects-driven ambiance (De Dood In Bloei). Speaking with Guitar World, the Amenra guitarists got into the controlled burn of their latest emotional wrecker.

The music from De Doorn had first been performed as part of a pair of fire rituals in Belgium. For those that may not be familiar with the practice, what exactly did that entail?

Lennart Bossu: “The fire rituals that we did were organized in the Flemish city of Ghent, and in Menen. During the fire ritual, people had a chance to burn their unacknowledged loss – things that you are grieving, but might seem trivial to other people. Like the loss of a person in your life, or it could be the loss of a pet, or whatever else you feel you are grieving. You had the chance to say goodbye, and have that unacknowledged loss [properly] acknowledged.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Mathieu Vandekerckhove: “The art piece we burnt in Ghent [was shown] two weeks before the event at the Vooruit Arts Centre. People could go there, write something personal on a piece of paper, grief, loss, anything and put it in the statue. Then we moved it to the site and burned it while we were performing. That was the ritual.”

Did you write anything down to put inside the structure?

Oathbreaker has become inactive. For me, writing De Doorn was a grieving process, to say goodbye to that

Lennart Bossu

Vandekerckhove: “I didn’t. For me the catharsis came from playing to the burning art piece. Performing is always a way for me to process the things that are happening around me and the feelings that I am having at that moment.”

Bossu: “I was in another band called Oathbreaker while we were writing these songs – still am, actually, but it’s become inactive. For me, writing [De Doorn] was a grieving process, to say goodbye to that.”

There must be something visceral to seeing these structures go up in flames during the rituals. Did that physical sensation change the properties of the songs as you were performing them?

Bossu: “It was a special experience, being there and feeling the heat from the flames as you’re performing. I guess we weren’t so much anticipating that while writing the songs, but it definitely intensified the performances. It made it this whole other experience, to be living in that moment with the crowd.”

Had the pieces gone through any changes by the time you laid them down in the studio?

Bossu: “We tweaked them here and there. Some parts were longer in their original form, because we were waiting for [specific moments] in the ritual to happen before we switched to another riff. [The recordings] are 90 per cent as we performed them, though.”

How did you go about writing your respective parts on the album? Pieces like the opening Ogentroost are full of these extended moments of chunky, unified riff-lording, but as the album moves on, it seems like you split apart from this approach towards a more atmospheric texturing.

Bossu: “I would say that Mathieu is the more atmospheric player. He will do more soundscapey, e-bow stuff. Everything you hear on the second track, De Dood In Bloei – the reverb-y, vibey stuff – that’s all Mathieu. I’m the more straightforward player of the two.”

Mathieu, has that generally been your approach in Amenra?

Vandekerckhove: “Maybe? I just play what comes out of me; I don’t put it in a box.”

Bossu: “I wouldn’t necessarily say that it’s always been like that. On previous records, [Mathieu] did a lot of the heavy riffing as well, but on this one it’s ended up that way.”

Was there much in the way of tone experimenting on this record?

The EarthQuaker Devices Levitation reverb was an important part of the clean sound on the album

Lennart Bossu

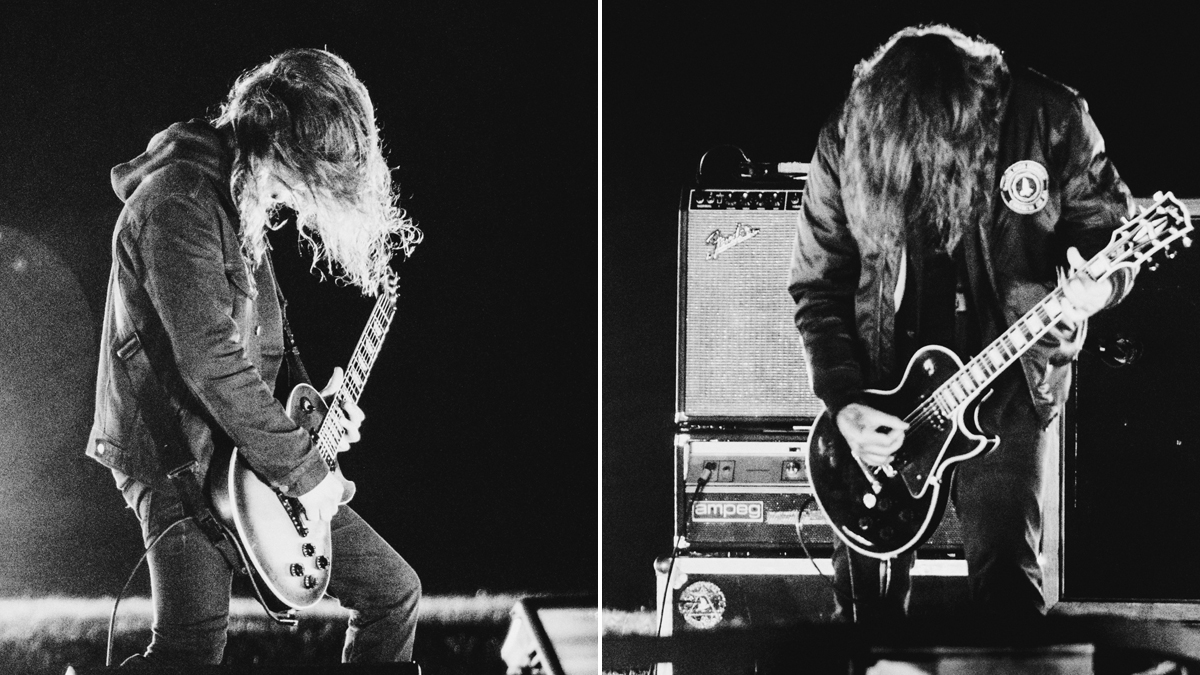

Bossu: “We stayed pretty close to what we use live. Live, we both use vintage Ampeg V4 amp heads – Mathieu used that on the album; I used my Marshall JMP just to have a bit more of a difference in tone. I guess you also used your Turbo Rat distortion, and a YGON cab – a small, custom cab builder from Belgium. With [my] Marshall, I used a Jimi Hendrix Marshall cab, a special anniversary edition.”

“We usually use Fender Twin Reverbs live for clean tones, but we had a problem with them in the studio. They were too noisy. Our bass player, Tim [De Gieter], recorded the album; he has a studio [Much Luv Studio in Lembecke, Belgium]. We started experimenting with clean amps and ended up with this weird amp that his father had made. I don’t know the specifics of it – I don’t even know if it was a tube or solid-state – but it was this brandless amp and it sounded fine. I also used the EarthQuaker Devices Levitation reverb; that’s an important part of the clean sound on the album.”

“90 per cent of the guitars [on the album] are our stage guitars. Mathieu has a Gibson Les Paul Custom, and for me it was a Les Paul Standard.”

Mathieu, how long has that Custom been your number one?

Vandekerckhove: “I got it three years ago, but before that I played a Gibson Studio. I’d bought [that] second-hand when I was 16 years old, and played it for 20 years. It was my only guitar at the time.”

Bossu: “Didn’t the headstock break?”

Vandekerckhove: “Yeah, and all the metal has corroded. I still have the guitar. It’s more like an art piece, now – I just moved to a new place, [and] that’s the idea, to hang it up.”

The album’s Het Gloren goes through an extreme ebb and flow – massive washes of distortion towards hyper-compressed moments of silence – it drops out like that a couple of times. How did you go about shaping the dynamics of the piece?

Bossu: “I don’t know if this is too philosophical, but I wanted the intro to have this hopeless, desolate feeling. That’s what I wanted to convey.”

Near the end of the piece, it rises towards this monumental juxtaposition of glacially paced drum hits and speedy, eighth-note trilling...

Bossu: “That’s both of us doing the tremolo picking – I think there’s actually three parts stacking on top of each other to create that big wash of sound. Also, [speaking on the transition from] the first heavy section and the section that begins with the clean part – that tonal shift – they don’t quite fit, but we liked how it shifted abruptly and uncomfortably.”

Later, you end the album’s Voor Immer with another crushing, melancholy riff. The higher melody playing has this crystalline, almost zither-like tone to it...

Bossu: “That’s also two guitars on top of each other. One person does the same three-note [melody] while the other one of us shifts a note each cycle. That’s that Levitation that I’d mentioned earlier – it gives it that crystalline quality. To be honest, though, Tim probably mixed it in a way to make it sound even nicer.

“Setup-wise, that’s the amp his father made, and if I’m remembering correctly, you [Mathieu] used a Telecaster for that. I also have this Nik Huber guitar that has a coil-split that I sometimes use when I need a thinner clean sound.”

There’s an older quote from [vocalist] Colin [H. Van Eeckhout] on performing with Amenra where he says that a “scream needs to hurt”. How does that thought resonate with either of yourselves, in terms of where you want to take your own performances and the emotions you hope to convey through the music of Amenra?

When you’re playing post-metal, it’s tempting to start filling up everything with melodies, but we try to limit ourselves in our choice of notes, and even how much we play

Lennart Bossu

Bossu: “When you’re playing post-metal, it’s tempting to start filling up everything with nice little melodies, [but] we try to limit ourselves in our choice of notes, and even how much we play. That takes it back to the essence [of Amenra]. When you’re playing the right notes, your impact is bigger.”

Since De Doorn sits outside of your six Mass albums, do you see this as a new beginning for Amenra or just part of the bigger picture?

Vandekerckhove: “We didn’t bill it as a Mass record because the basic concept was different – it all started by creating songs for the rituals.

Bossu: “It’s definitely its own thing, even just for the fact that it’s all sung in [Flemish] Dutch, for instance. I don’t know if that will ever happen again. On the other hand, it also has its place within the body of work of Amenra. It’s not [that] super-weird or different.”

- De Doorn is out on June 25, and available to preorder now via Relapse Records.

Gregory Adams is a Vancouver-based arts reporter. From metal legends to emerging pop icons to the best of the basement circuit, he’s interviewed musicians across countless genres for nearly two decades, most recently with Guitar World, Bass Player, Revolver, and more – as well as through his independent newsletter, Gut Feeling. This all still blows his mind. He’s a guitar player, generally bouncing hardcore riffs off his ’52 Tele reissue and a dinged-up SG.

“We hadn’t really rehearsed. As we were walking to the stage, he said, ‘Hang on, boys!’ And he went in the corner and vomited”: Assembled on 24 hours' notice, this John Lennon-led, motley crew supergroup marked the beginning of the end of the Beatles

“I pushed myself to down-pick faster and make the riffs more aggressive. Maybe it’s the old man in me struggling to feel young and fighting back against aging”: How Killswitch Engage went to thrash metal bootcamp to deliver their face-ripping return

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)