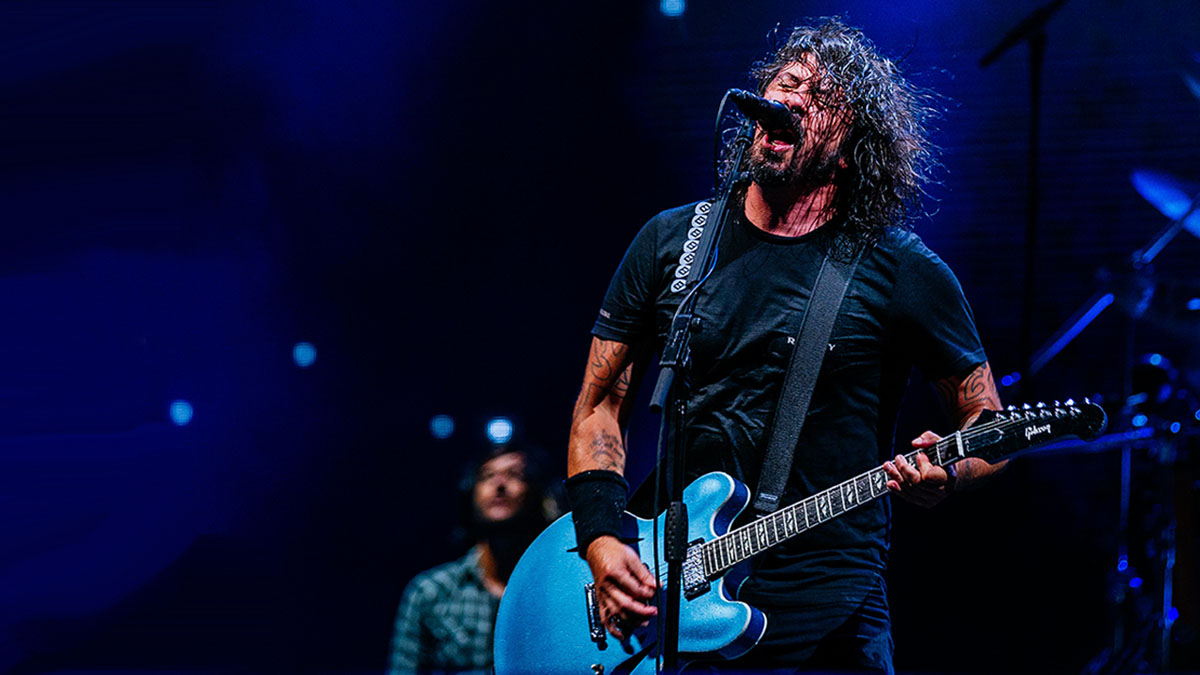

A brief history of the Foo Fighters' remarkable quarter-century career

Okay, it's been 26 years, but who's counting? Dave Grohl unpacks the unlikely mega-stardom of the drummer turned frontman

“There's a famous old joke: what was the last thing the drummer said before they kicked him out of the band? ‘Hey guys, I got a new song I just wrote!’”

Dave Grohl told this oldie-but-goodie to Guitar World back in 1997 to describe his mindset during the Nirvana days, when he was not only, yes, the drummer, but also the drummer in a band that had already been through six of ’em previously (“and when you’re the seventh drummer, it would be pretty big-headed of you to imagine yourself being the final drummer,” he acknowledged).

What’s more, Kurt Cobain, the guy who was up front singing and playing guitar and writing Nirvana’s songs? He also happened to be one of the greatest – if not the greatest, in many people’s eyes – songwriters of his generation.

All of which meant that Grohl was happily resigned to bashing away behind the kit with Nirvana, which he did – rather excellently, we might add – from 1990 to 1994. Of course, we all know what happened next – even if, at the time, the future wasn’t very clear for Grohl.

Following Cobain’s death in April 1994 from a self-inflicted gunshot wound, Grohl initially dropped out of the public eye, traveling, spending time with his family and friends and generally just staying away from music.

Eventually he picked up the drums again, recording the soundtrack to the fictionalized Beatles movie Backbeat as part of an all-star band, and also playing with Tom Petty, who went so far as to offer Grohl the drumming gig in the Heartbreakers. “It was such an honor,” Grohl told Rolling Stone in 1995. “But I figured that I was 26 years old and didn’t want to become a drummer for hire at the age of 26.”

There was also another factor in his decision to pass on Petty. Beyond not wanting to be a mere hired gun, Grohl, musty old drummer jokes aside, also had songs.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Some of these dated back to the Nirvana days – one of them, a gentle tune titled Color Pictures of a Marigold (aka Marigold), with Grohl on vocals, drums and guitar, was even released as a B-side on Nirvana’s Heart-Shaped Box single (a version also appeared on a 1992 album, Pocketwatch, that Grohl released under the pseudonym Late!).

Another song, a grunge-pop rager titled Alone + Easy Target, Grohl has played in demo form for Cobain during a break between Nevermind tours in 1991.

Cobain, he recalled to Mojo, “was sitting in the bathtub with a Walkman on, listening to the song, and when the tape ended he took the headphones off and kissed me and said, ‘Oh, finally, now I don’t have to be the only songwriter in the band!’ I said, ‘No, no, no, I think we’re doing just fine with your songs.’”

Which was truly how he felt. And which was also why, when Grohl, now band-less, entered Robert Lang Studios in Seattle in October 1994 to record some of his own songs – playing all the instruments himself, no less – he wasn’t thinking much beyond making a demo mostly to hand out to friends.

“I kind of just pulled myself up and thought, ‘Okay, I’ve always loved playing music and I’ve always loved writing and recording songs for myself, so I feel like I need to do that just for myself,” he told Apple Music earlier this year.

As for why he credited the collection, recorded in under a week, to the “band” Foo Fighters? “I wanted people to think that it was a group,” he explained, adding, “Had I actually considered this to be a career, I probably would have called it something else, because it’s the stupidest fucking band name in the world.” Stupid or not, the name stuck.

The demo, which featured now-classic Foo Fighters songs like This Is a Call, the aforementioned Alone + Easy Target and the buoyant, sticky-sweet Big Me, demonstrated that, like Cobain, Grohl’s songwriting managed to wrangle all the disparate music he loved – punk and hardcore like Bad Brains and Hüsker Dü; sludgy art-damaged metal like the Melvins; power-pop like Cheap Trick and the Bay City Rollers; as well as a healthy dose of '80s alt and indie sounds and straight-ahead '70s riff-rock – into insanely catchy and often uniquely arranged modern aggro-rock anthems.

I loved the Beatles when I was a kid, but I loved the Bad Brains too. And there were a lot of bands in the early to mid-'80s that were a perfect blend of those things

“I loved the Beatles when I was a kid, but I loved the Bad Brains too,” Grohl told Guitar World. “And there were a lot of bands in the early to mid-'80s that were a perfect blend of those things.

“Hüsker Dü had a searing guitar sound and breakneck speeds, but they’d do that as they were covering the Byrds’ Eight Miles High. It was just beautiful and powerful. I think that’s probably where it all comes from. It’s not necessarily blueprinted or calculated.”

Not surprisingly, Grohl’s modest demo wound up making its way around the industry; before he knew it, he had plenty of label interest. What he didn’t have was a band. While Grohl had spoken with former Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic about coming on board, they eventually determined it would have loaded down the nascent project with too much baggage and expectation.

Instead, Grohl recruited bassist Nate Mendel and drummer William Goldsmith, both of recently defunct Seattle emo act Sunny Day Real Estate, as well as In Utero-era Nirvana touring guitarist Pat Smear, and hit the road. With Grohl still press-shy in the wake of Cobain’s tragic death, the Foo Fighters had a deliberately low-key launch.

They played a few intimate club dates, and then piled into a van to tour small clubs as the support act (and also backing band) for one of Grohl’s heroes, former Minuteman Mike Watt; it is the routing for this series of spring 1995 shows that the Foos had planned to reenact for their 2020 “van tour” celebrating their 25th anniversary.

“That was a fun tour,” Smear tells Guitar World today. “It was a real adventure. Plus we got to play twice every night!”

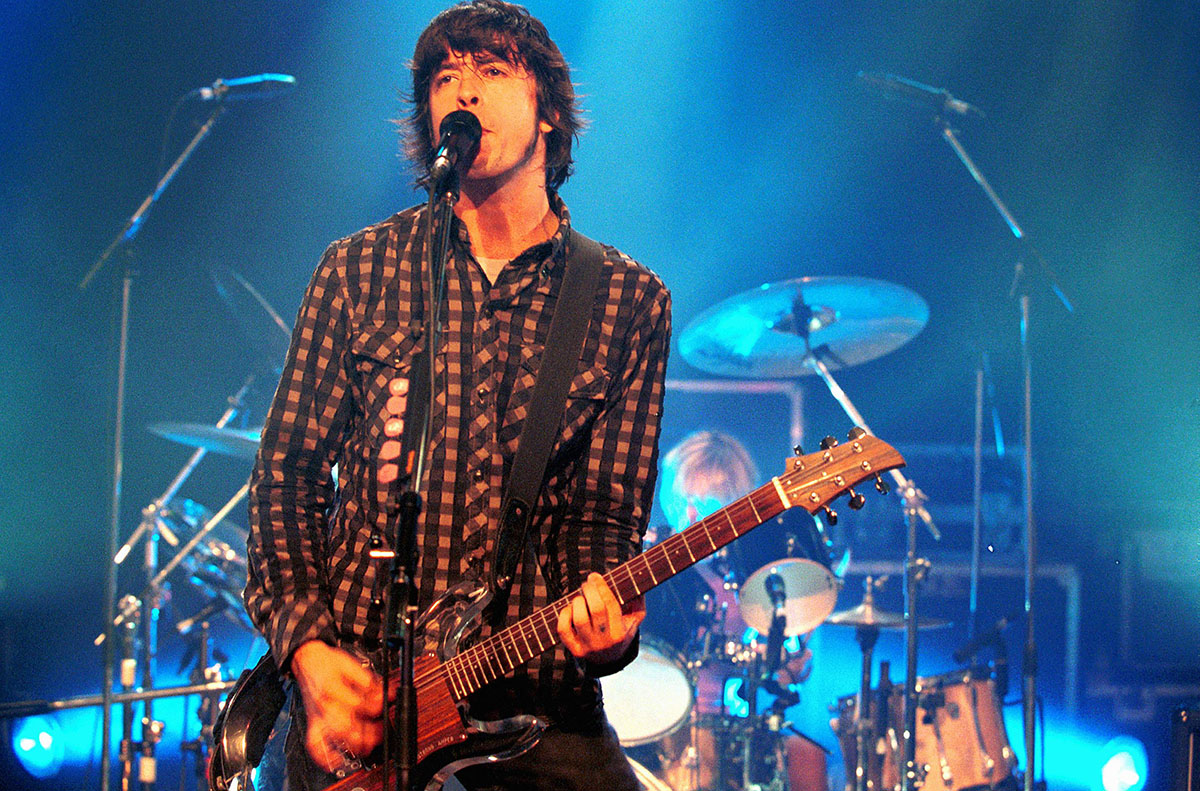

Of course, things didn’t stay low key in the Foos world for long: In the spring of 1995 Capitol Records (via Grohl’s own Roswell Records imprint) released Foo Fighters, and the album hit big. By the summer the band was playing the Reading Festival to tens of thousands of fans, and in less than a year Foo Fighters went platinum, with the videos for I’ll Stick Around and Big Me in constant rotation on MTV.

The Foos’ early years, however, weren’t all smooth sailing. Their next album, 1997’s The Colour and the Shape, was the first recorded as a full band, but during its recording drummer Goldsmith exited acrimoniously, after Grohl replaced the majority of his drum tracks with his own playing (later on, during the tour in support of the album, Smear, citing exhaustion, left the band as well, replaced for a short period by Grohl’s childhood friend Franz Stahl).

The album’s subject matter, meanwhile, dealt largely with Grohl’s recent divorce from his first wife, photographer Jennifer Youngblood.

At the same time, The Colour and the Shape signaled several landmark moments in the Foos’ career. For starters, Goldsmith’s exit opened the door for former Alanis Morrisette touring drummer Taylor Hawkins, a monster musician who not only remains a key Foo to this day, but also serves as Grohl’s onstage foil and, often, comedic counterpart in interviews and music videos.

Furthermore, The Colour and the Shape, which saw Grohl move from the lo-fi grunge of the debut album toward a more hard-hitting and direct rock sound, was a massive success, launching three hit singles – the raging Monkey Wrench, the swelling My Hero and the indelible Everlong – and selling more than two million copies in the process.

With the success of The Colour and the Shape, the Foo Fighters were firmly established as one of the major rock acts of the late Nineties, with Grohl now recognized as much for his singing, songwriting and guitar playing with his own band as for his previous drumming work with Nirvana.

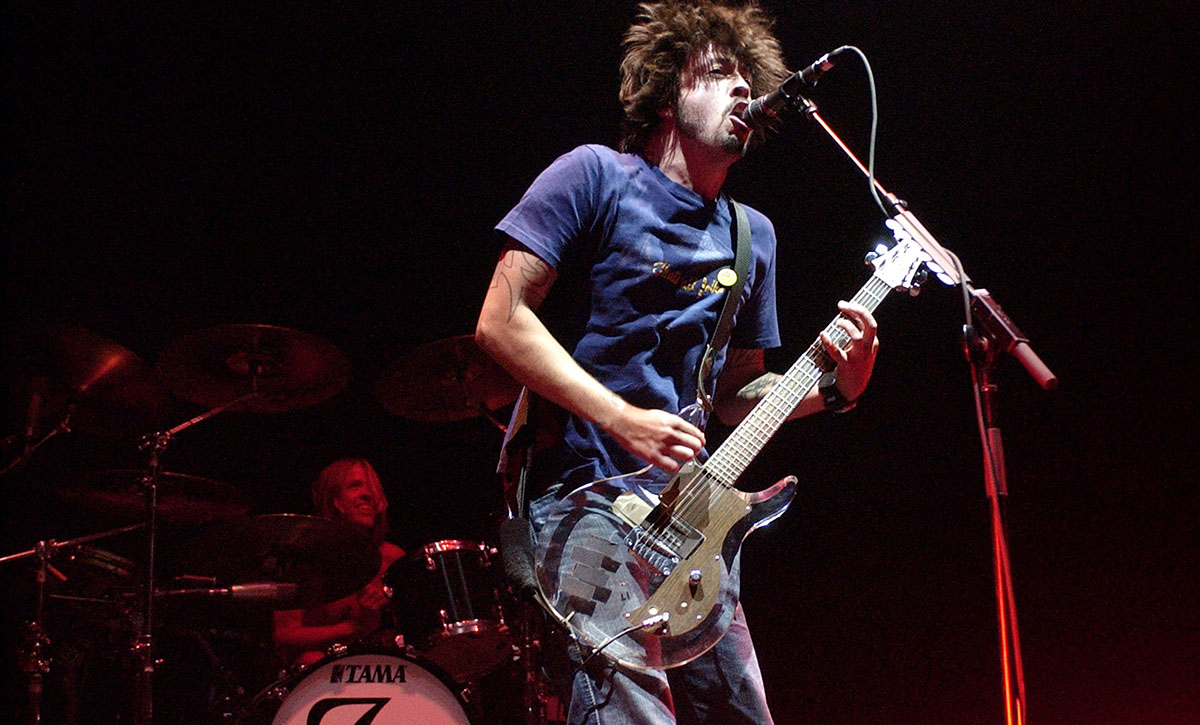

And while the Foos would remain incredibly consistent both in the studio and on the road, they didn’t rest on their laurels. Their next album, 1999’s There Is Nothing Left to Lose, saw the trio of Grohl, Mendel and Hawkins (Stahl had by this time departed) exploring a softer, more melodic sound.

“At the time, music was going through this nü-metal shift, and it was all screaming choruses with distortion pedals and creepy, quiet verses,” Grohl told Guitar World. “It was all really in-your-face and brash. So we made that third album intentionally mellow by our standards, because it had become boring and all too easy to scream and step on your distortion pedal.”

The effort launched the band’s then highest-charting single to date, the textured and chiming Learn to Fly, and also nabbed a Grammy award – their first, but hardly their last – for Best Rock Album.

From there, the Foos continued to explore. Their next record, One by One, was the first to feature current guitarist Chris Shiflett, who brought a harsher, punkier edge to tracks like lead single All My Life.

Following that came the double album In Your Honor, which hosted one record of electric rockers (including the anthemic Best of You, which Prince famously covered during his 2007 rain-soaked Super Bowl halftime performance – “my proudest musical achievement,” Grohl has said) and one of mellower acoustic songs (among them Friend of a Friend, a re-recording of a track from Grohl’s 1992 Pocketwatch album).

Regarding the acoustic side of the double album, Grohl told Guitar World, “One of my favorite albums of all time is Ry Cooder’s Paris, Texas. So I envisioned finding a project that I could turn into my own version of Paris, Texas. After about a month of writing I thought, wait a second, this could be a killer Foo Fighters record.”

2007’s Echoes, Silence, Patience & Grace, meanwhile, brought the electric and acoustic personalities of the band into more direct contrast, alternating lighter fare like Long Road to Ruin and the pastoral Stranger Things Have Happened with angular and abrasive tracks like Erase/Replace and the crushing The Pretender, and imbuing the whole thing with an adventurous, at times almost proggy approach to structure and arrangements.

“There’s four-piece rock band shit,” Grohl told Billboard about the album, “but then there are songs where the middle sections turn into this mass orchestrated swarm and ridiculous time signatures.”

By the time of 2010’s Wasting Light (which also saw the return of Smear as a full-time member), the band had shifted focus once again, opting to record a back-to-basics rock record on fully analog equipment… in Grohl’s garage. Also along for the ride was producer Butch Vig, who had famously produced Nirvana’s Nevermind almost 20 years earlier.

“Our last few records were really focused on exploring new musical ground,” Grohl told Guitar World. “As you keep making records, you want to excite yourself. You want to prove the band’s musicality, diversify and not make the same album every time.

But inevitably you start to crave that feeling that you had when you made the first or second record. You go so far away from that to explore new and different things that, after a while, you miss the simplicity of plugging in, turning up to ten and screaming your balls off.”

Not surprisingly, the Foos did a complete 180 for their next record, 2014’s Sonic Highways, trading in simplicity in favor of crafting what is arguably their most ambitious outing to date.

As you keep making records, you want to excite yourself. You want to prove the band’s musicality, diversify and not make the same album every time

For the album (which was also paired with an HBO documentary miniseries of the same name), the band recorded each song in a different U.S. studio, joined each time by guests – ranging from Gary Clark, Jr. and Joe Walsh to Zac Brown and Cheap Trick’s Rick Nielsen – with ties to the particular city they were in. “The scope of this thing,” Grohl said to Britain’s NME, “was fucking crazy.”

By that point, however, Grohl, both with and without the Foos, had been on a crazy run of his own, from teaming up with Queens of the Stone Age’s Josh Homme and Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones in the side project Them Crooked Vultures, to producing the 2013 documentary Sound City, chronicling the history of the fabled L.A. studio where artists like Fleetwood Mac, Tom Petty, Neil Young and, yes, Nirvana, had recorded landmark albums.

He also put together the Sound City Players supergroup – featuring his Foo Fighters band mates and others alongside revolving guests like Paul McCartney, Stevie Nicks and Trent Reznor – to perform select live shows around the release of the film.

As for the Foo Fighters, there’s been little down time ever since, with more tours and recordings, including 2015’s Saint Cecilia EP and 2017’s Concrete and Gold full-length, as well as the brand-new Medicine at Midnight. And while Grohl tells us that “if this were the last record, we would be happy with what we’ve done,” it’s clear that, a solid quarter-century in, he has no intention of Medicine at Midnight being the final Foo Fighters statement.

We all decided that we’d get together and have a band and use these songs to jump in the van and go have fun. It was that way for maybe the first 12 years, and then it turned into something else where we were like, ‘Okay, well, we can’t stop now!’

“The foundation of the band is funny because originally it was just a demo tape I made,” Grohl says. “And then we all decided that we’d get together and have a band and use these songs to jump in the van and go have fun. We did that, and then we looked at each other and said, ‘Okay…do you want to do it again?’

“Some of us did and some of us didn’t, but we kept the band going and we did it one more time. And then we looked at each other after that and said, ‘Again?’ So we did it again. And again. It was that way for maybe the first 12 years, and then it sort of turned into something else where we were like, ‘Okay, well, we can’t stop now!’”

Grohl laughs. “So I always say that the idea of this band ending is like the idea of seeing your grandparents get a divorce – it’s just not going to fucking happen!”

- Foo Fighters' new album, Medicine at Midnight, is out now via RCA.

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.

“The main acoustic is a $100 Fender – the strings were super-old and dusty. We hate new strings!” Meet Great Grandpa, the unpredictable indie rockers making epic anthems with cheap acoustics – and recording guitars like a Queens of the Stone Age drummer

“You can almost hear the music in your head when looking at these photos”: How legendary photographer Jim Marshall captured the essence of the Grateful Dead and documented the rise of the ultimate jam band