20 legendary players who shaped the sound of electric bass

The iconic bassists who developed the sound of low-end as we know it

Tone. Described with our woefully limited vocabulary - warm, nasty, mellow, searing, scooped - it’s one of the more esoteric ingredients in the making of a bass player. But the best chops played through the finest gear will fall on deaf ears if that crucial ingredient isn’t in place.

Here, we look at 20 players who have shaped our tone vocabulary. Read. Reflect. Discuss. There are countless others of course, but these are some of the most influential players who have forged the sound of the electric bass as we know it...

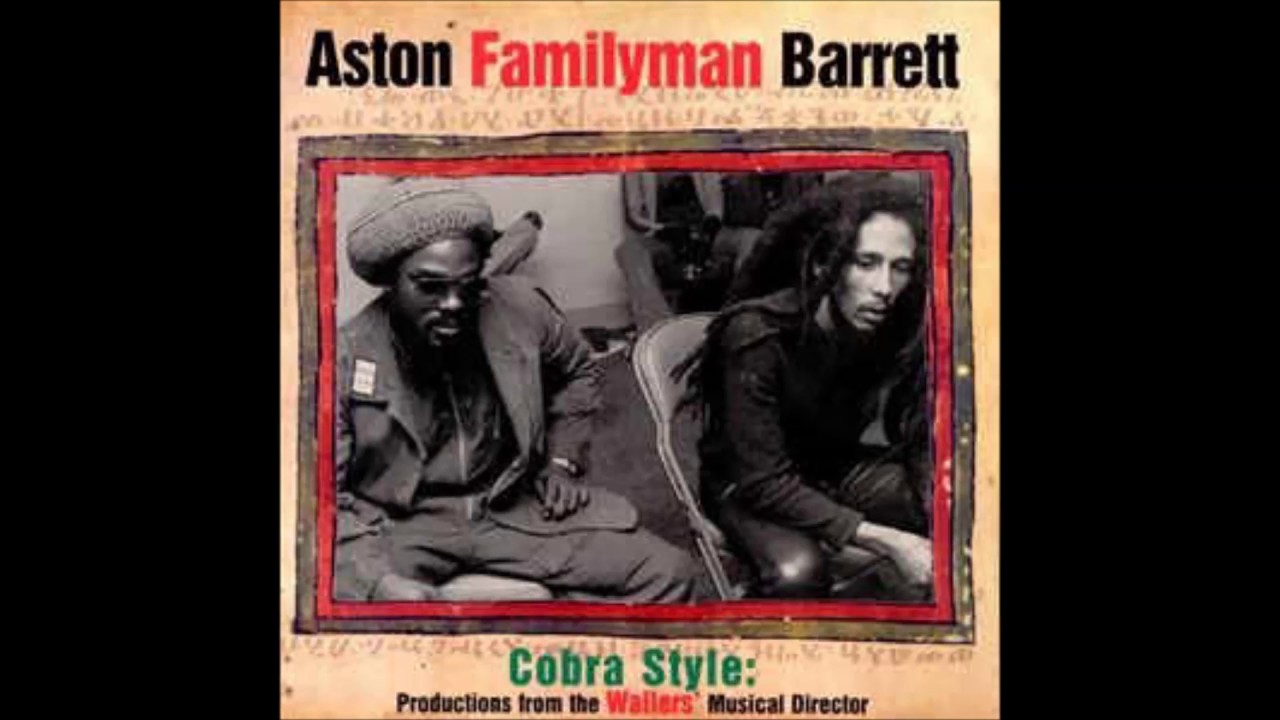

1. Aston “Family Man” Barrett

Perhaps no music evokes the notion of bass and bass tone like reggae and dub, and no two words are more synonymous with those plucking practices than “Family Man.”

The Bob Marley bassist invented the concept of a melodic line locked into the groove, the “one-drop” downbeat, and various other stylistic approaches to Island bottom. Barrett plucks with both index and middle fingers or thumb, with his left hand usually settling in the middle of the neck, around Eb on the A string.

Focused on presence over sheer volume onstage or in the studio, “Fams” possesses a warm, full-bodied sound that’s both the hypnotic heartbeat of the song and often the melodic or rhythmic subhook, as well—a knack also mastered by his plucking protégé, fellow reggae bass legend Robbie Shakespeare.

In his October 2007 BP cover story, Family Man summed up his tone. “I call it the ‘earth sound.’ When I was young, Lloyd Brevett was one of my favorite bass players from Jamaica, and he played upright bass. I always try to grab that sound when I’m playing the electric bass.”

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Bass Fender Jazz Bass

Rig Acoustic 360, Eden WT800

Strings Fender flatwounds

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Bob Marley & The Wailers, Natty Dread [Island, 1974]

Bob Marley & The Wailers, Exodus [Island, 1977]

Burning Spear, Social Living [Island, 1978]

2. Jack Bruce

If not for the limitations of gear in the early days of amplified music, the bass world would be a boring place. Take for example, the downright nasty midrange growl that characterizes the majority of blues-rock legend Jack Bruce’s recorded output with Cream.

Though Cream - arguably rock & roll’s original supergroup - had a tenure of just a few years, Bruce used his time on the world’s stage to codify an aggressive tone that would influence even the great Jaco Pastorius.

“In the original Cream we had Marshall stacks with only one or two speakers working; that’s what gave me my trademark, ‘farty,’ distorted tone,” Bruce told BP in December 2005. “On 90 percent of the gigs there was no proper PA or any monitoring, so the sound we got was the sound onstage.”

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses Gibson EB-3, Gibson EB-O, Fender Bass VI, Warwick Thumb Bass

Rig Marshall stacks, Hartke HA-5500 heads, Hartke VX810 and 115XL cabinets

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Cream, Disraeli Gears [Polydor, 1967]

Cream, Wheels of Fire [Polydor, 1967]

Jack Bruce, Songs for a Tailor [Polydor, 1969]

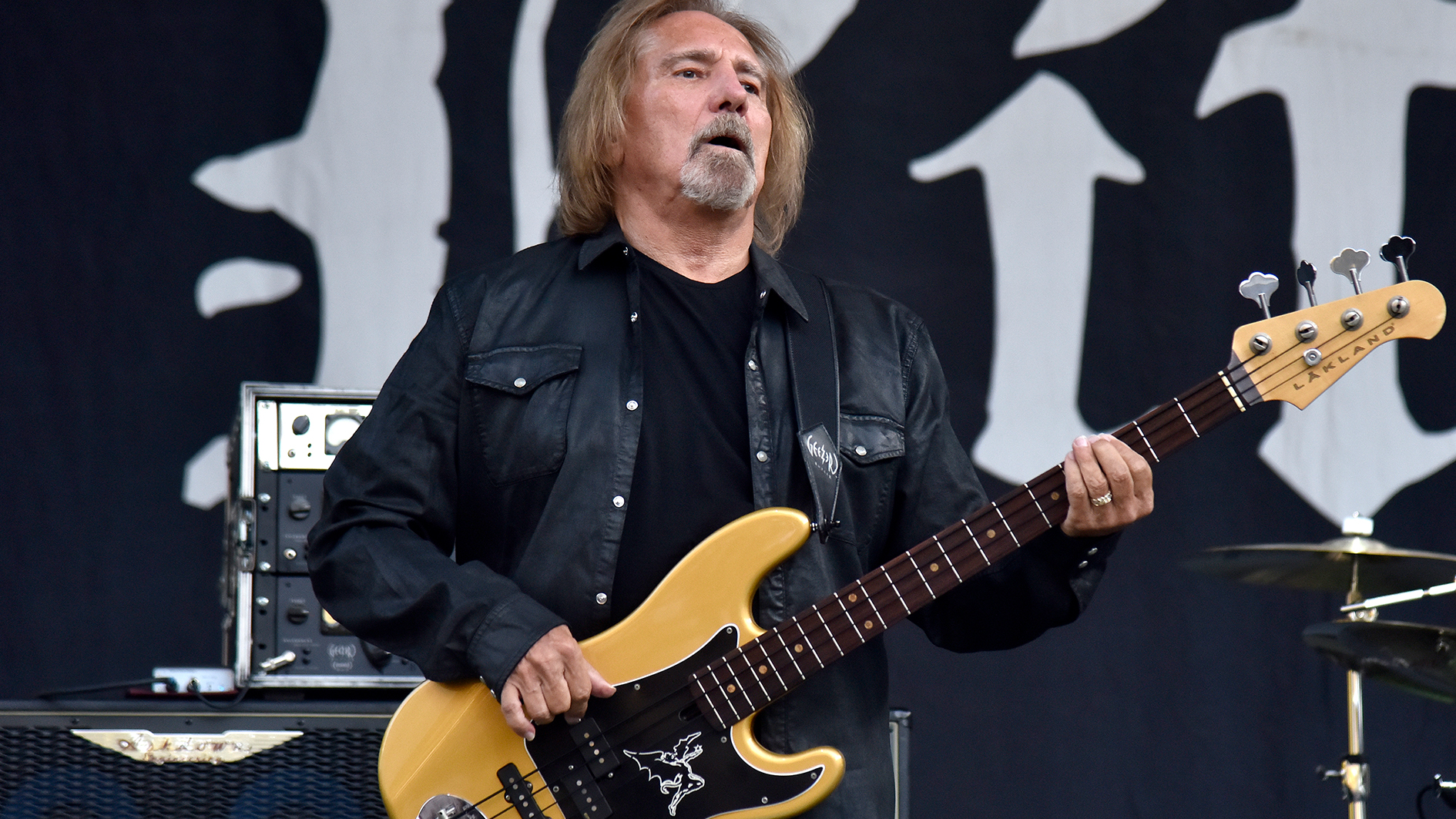

3. Geezer Butler

If Ozzy Osbourne is worthy of his title as the Godfather of Heavy Metal, Ozzy’s Black Sabbath bandmate Geezer Butler is certainly the Godfather of Heavy Metal Bass.

On the band’s early records, the Birmingham bass brawler’s brawny sound came courtesy of a detuned Fender Precision bass played through a stack of semi-blown speakers.

“So many people ask me how I got the bass tone on the first [Black Sabbath] record,” Geezer said in his July 2004 Bass Player cover story.

“It was by accident! I had a 70-watt Laney guitar amp and a Park 4x12 cabinet with only three speakers in it—and two of them were wrecked, That’s how I got that really distorted sound.

“At times I’ve hated my sound, and I’ve tried to dial in whatever sounded modern at the time. It never worked. I remember trying to sound like Chris Squire [of Yes]. Ozzy’s reaction was, ‘What the hell is that?’ I was attempting to get a sound I liked to listen to, but it didn’t fit my playing style.”

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses Fender Precision Bass, Vigier

Rig 70-watt Laney guitar amp, Park 4x12 cabinet

Effects Tycobrahe wah and flanger

Strings Rotosound

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Black Sabbath, Black Sabbath [Vertigo, 1970]

Black Sabbath, Paranoid [Vertigo, 1970]

Black Sabbath, Master of Reality [Vertigo, 1971]

4. Stanley Clarke

When you’re a low-end lord with the gift to forever change the face of bass, no standard brand of 4-string will do. Thus, in the early ’70s, while Stanley Clarke was innovating such concepts as slapping in jazz, horn-like solos (including screaming sheets-of-sound), piccolo and tenor instruments, and band-leading as a jazz bass guitartist, he did so with a tone all his own via Alembic basses.

From his liberating solo albums and landmark sides with Return to Forever to projects with George Duke, Keith Richards’ New Barbarians, Paul McCartney, Animal Logic, and SMV (with Victor Wooten and Marcus Miller), Clarke’s electric tone has remained consistent: percussive, taut, and with a clear high end.

Stanley’s sound is also shaped by his plucking the strings mainly over his neck pickup, and of course his experience developing and drawing a sound from his main axe, the acoustic bass.

Clarke spoke about the challenges of capturing his super sonics in the studio, in BP’s March 2003 issue.

“For years my ‘secret’ was to tape through a compressor/limiter like an old Fairchild or Manley or Trident, and then out again through a second compressor. A bass note’s wave form develops over time; the longer the note exists the bigger it is, and the faster it happens the smaller and tighter the wave is.

“Because I tend to play the bass very fast, there’s no time for the notes to sound fully—so I was able to capture more of each note by getting into various types of compression. I’ve also found that units like the Fairchild or the Summit can handle the sound of Alembics and other high-end basses without losing any of the excitement of the tone.”

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses Alembic standard and tenor 4-strings; Carl Thompson piccolo 4-string

Strings Rotosound

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Stanley Clarke, School Days [Epic, 1976]

Return to Forever, Romantic Warrior, [Sony, 1976]

Stanley Clarke, 1,2, To the Bass [Sony, 2003]

5. Bootsy Collins

B-B-B-Bootsy! Bootsy Collins first turned the bass world on its ear during his brief tenure with James Brown, but it was Bootzilla’s Mu-Tron-infused work with George Clinton and Parliament that had the most profound effect on the future sound of funk.

As Bootsy told BP in November 2010, the challenge of finding the right tone was itself a catalyst for creativity.

“The old Mu-Trons and Big Muff [pedals] were all slightly different, so you had to work with them. To me, that was the fun. It helped push your creativity. Pedals are so preset and consistent now that they all sound the same.

“At F.U. [Bootsy’s online Funk University], we’re trying to get away from the domestication of sound. I’m not knocking manufacturers, but I want musicians to avoid getting locked in on a particular sound that everybody’s using. Find your own.

“Comedians always say that timing is the key—you have to be on point. It’s the same thing with playing the bass and using pedals. You can’t just step on a pedal and expect people to react. It’s about making the pedals say something. That’s really a gig in itself, but I enjoy it. I’m sitting in front of some pedals I’m recording with right now.”

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses Fender Precision Bass, Larry Pletz Space Bass

Rig Alembic F2B preamp, Crown Micro 5000 and Micro 3600 power amps, Electro- Voice 4x18, 4x15, and 8x10 cabinets

Effects Mu-Tron III Envelope Follower, Electro-Harmonix Big Muff, Morley Power Wah Fuzz

ESSENTIAL SIDES

James Brown, Sex Machine [Polydor, 1970]

Parliament, Mothership Connection [1976]

Bootsy’s Rubber Band, Stretchin’ Out In Bootsy’s Rubber Band [Warner Bros., 1976]

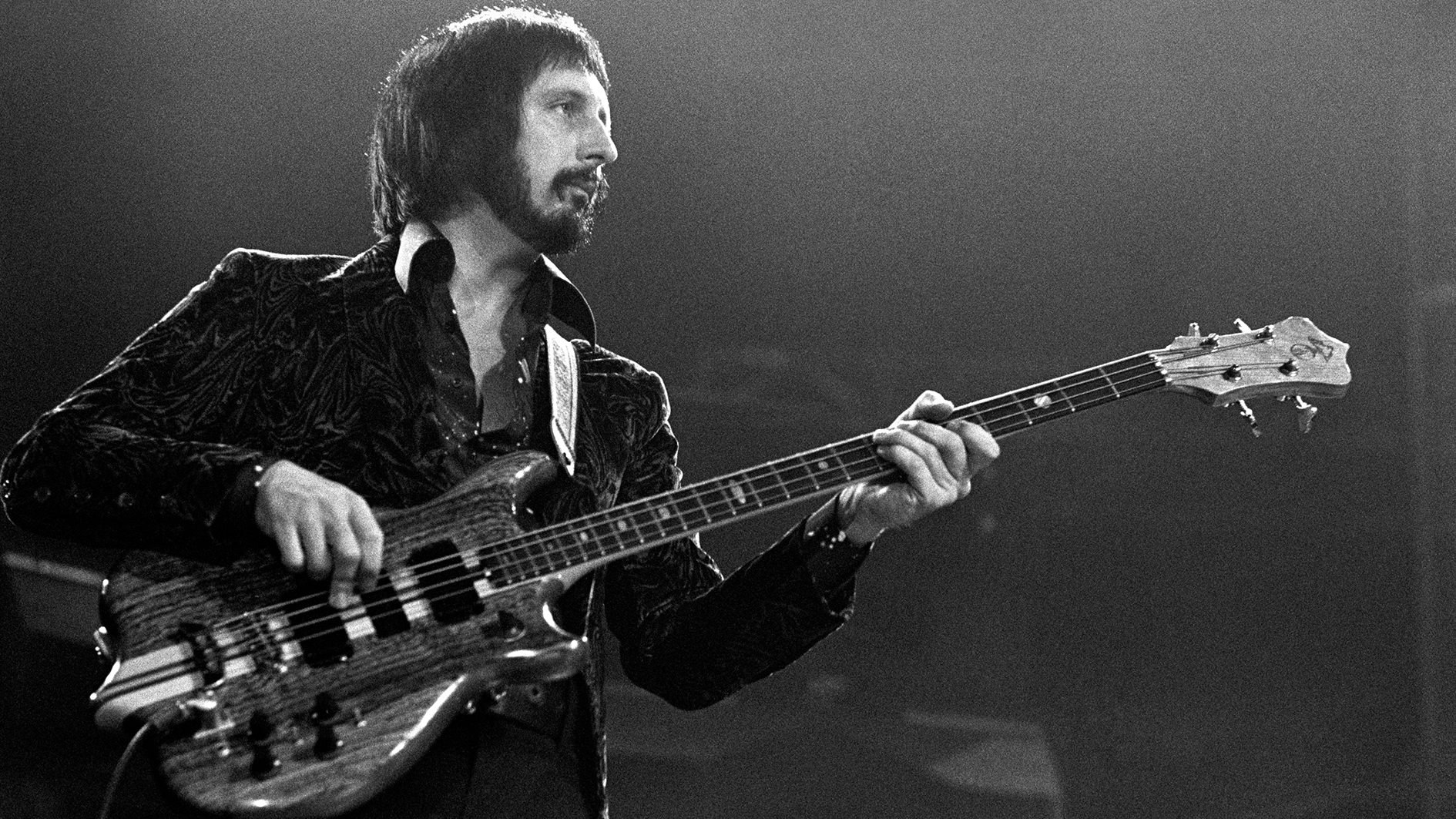

6. John Entwistle

How ahead of the curve was the Who’s John Entwistle, tone-wise? The Ox, who stands as rock’s first bass virtuoso and a cornerstone pioneer on the instrument, couldn’t get the sound he was hearing in his head until the band was well into its second decade and gear (and engineers) began to catch up to his ideal.

By then, Entwistle had taken the first bass solo on a major rock single (1965’s “My Generation”), developed roundwound strings with Rotosound, and introduced the concept of bi-amping. Finally, his revolutionary technique and tone concepts were heard in their full glory, thanks to a favorable mix on 1978’s Who Are You.

These included fingerstyle and pick playing, chord strums, stringpops and smacks, harmonics, “crab-claws” (octave grabs with thumb and index finger), and his tapping predecessor, “typewriting technique,” in which he struck the strings at the base of the neck with his four right-hand fingertips—all delivered with shimmering highs, crackling mids, and thunderous pianostring- like lows.

Chris Squire, Geddy Lee, and Billy Sheehan are among countless thumpers deeply influenced by the Ox’s sonic strides.

In BP’s September 2002 cover retrospective, the late Entwistle was recalled telling Guitar Player in 1989, “I’ve never considered myself to be a proper bass player. I’ve always been a bass guitarist, emulating guitar players. I played along with records by Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent, the Ventures, the Shadows, and especially Duane Eddy. His guitar had the sound I wanted my bass to have.”

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses Gibson “Fenderbird” (Thunderbird with a P-Bass neck), Alembic Explorer, Warwick Buzzard, Status Buzzard

Rigs Marshall, Vox, Sunn, bi-amped rigs by Ashdown and Trace-Elliot

Strings Rotosound; Maxima Gold

ESSENTIAL SIDES

The Who, Live At Leeds [MCA, 1970]

The Who, Who Are You [MCA, 1978]

John Entwistle, Whistle Rhymes [Sundazed, 1972]

7. Matthew Garrison

When you consider how much innovation and assimilation has occurred on the electric bass since it was accepted in jazz in the ’70s, via names like Jaco, Stanley, Marcus, Patitucci, and Wooten, it’s hard to believe a new voice with his own loyal legion could emerge so soon.

Enter Matt Garrison with his exploding collision of unrelated lydian major chords, memorable melodies, and world rhythms, centered around his 5-string (restrung with a high C), and delivered via ear-grabbing close-voiced chords and four-finger flurries.

The ensuing wave of high C 5-stringers plucking fingerstyle, with thumb, index middle, and ring finger can now be heard globally. The kicker? With Matt’s current MIDI/computer/ surround-sound explorations he’s likely the future of tone, as well.

In his February 2001 BP feature, Garrison revealed another tone secret; how he gets his Indian sitar sound. “I fret the target note and the next highest note with my left-hand index and middle fingers, and I position my right index finger above another note in the scale higher up the fingerboard. Then I tap that high note and pull off to the target note from the fret above in one quick motion.”

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Bass Fodera Matthew Garrison Imperial 5-string (33"-scale)

Rig Epifani heads and cabinets

Strings Fodera Matthew Garrison Nickel Roundwounds

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Matthew Garrison, Matthew Garrison [GJP, 2001]

Matthew Garrison, Shapeshifter [GJP, 2004]

Herbie Hancock, Future to Future: Live (DVD) [Sony, 2002]

8. Larry Graham

“I’m gonna add some bottom so that the dancer’s just won’t hide,” sang Graham on the title track to Sly & the Family Stone’s album Dance to the Music [1968].

Take that, Graham’s fuzzed-out breakdown on the Family Stone’s “I Want To Take You Higher,” and the “thumpin’ and pluckin’” Larry laid down on Graham Central Stations’s “Hair,” and you can bet bassists were coming out of the woodwork to take notice of Graham’s revolutionary approach to the bass.

“I started thumpin’ and pluckin’ from the first time I played bass,” Graham revealed to BP in May 2007. I would thump the strings with my thumb to make up for the bass drum, and pluck the strings with my fingers to make up for the backbeat snare drum.

“It made sense to me because I had been a drummer in the school band. I wasn’t interested in learning the so-called “correct” overhand style of playing bass, because in my head I was going back o guitar, anyway. Then I realized, Hey—this is pretty cool.” You don’t say, Mr. Graham...

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses 1960 Fender Jazz Bass, Moon bass

Rig Acoustic 360

Strings Rotosound (light gauge black nylon)

Other Roland Jet Phaser, Morley Power Fuzz Wah, Maestro Fuzz Phaser, Mu-Tron Octave Divider

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Sly & the Family Stone, Dance to the Music [Sony, 1968]

Sly & the Family Stone, Stand! [Sony, 1969]

Graham Central Station, Graham Central Station [Warner Bros., 1973]

9. Anthony Jackson

As the inventor of the 6-string contrabass guitar, Anthony Jackson certainly knows about bass tone. Jackson has always maintained the electric bass guitar is part of the guitar and not the viol family—with his ideal sound being that of a guitar dropped an octave or more.

The two key bass influences on Jackson’s sonic approach are the fat fundamental of Motown master James Jamerson and the rich, metallic sound of Jack Casady with the Jefferson Airplane. To that end, Jackson disciples recognize that Anthony has innovated several tone concepts.

There’s his penetrating “pick ’n’ flanger” sound, famously first heard on the O’Jays’ 1973 hit, “For the Love of Money.” There’s the powerful punch of his palm-muted plucks (with thumb, fingers, or pick), initally from his attempt to duplicate the sound of the Ampeg Baby Bass in Latin music. There’s his volume pedal-controlled melody readings, inspired by the French ondes Martenot.

But mostly, bassists relate to Jackson’s massive, full-range sound, which always sits below or even with the kick drum, frequency-wise, while retaining the overtone brilliance of grand piano bass notes and the new-string edge to cut through the ensemble.

In his December 2008 BP cover story, Anthony spoke about his initial reaction to having six strings, “Basically, I felt like the concept had worked. I focused on exploring the low B initially, and being conscious of not overusing it. The higher range seemed akin to the overlapping ranges of, say tenor and baritone saxophones, or viola and violin, where there are many notes in common, yet they sound different respective to the instrument. I could play into the guitar range, but with a throatier voice.”

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Bass Fodera Anthony Jackson Presentation Contrabass Guitar

Amp Millennia Media preamps; Meyer Sound cabinets

Strings Fodera Anthony Jackson bare-core roundwounds

Other Ernie Ball Stereo Volume Pedal; Waves “MetaFlanger” plug-in; Fender heavy picks

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Chaka Khan, What Cha’ Gonna Do For Me [Warner Bros, 1981]

Michel Camilo, Triangulo [Telarc, 2002]

Anthony Jackson/Yiorgos Fakanas, Interspirit [ANA Music, 2010]

10. James Jamerson

In the mighty hands of Motown’s James Jamerson, the benchmark for early, old-school, and eternal electric bass tone was established through an exotic list of components.

This includes Jamerson’s high aptitude on upright bass, his affinity for the electric bass, the musicians and atmosphere in the sweaty “snake pit” at Motown’s Hitsville Studios, and James’s dominant role as Funk Brother #1 on those sessions.

More specifically, Jamerson’s ’62 P-Bass featured high action (with open E, open A, and Bb on the A string being especially choice), foam under the bridge cover, and never-changed, heavygauge flatwounds. He plugged it direct into Motown’s tube console, boosting the volume on the input to get the VU meter slightly in the red, to provide a touch of warm overdrive.

A Fairchild limiter and Pultec EQ where also key in the mix, and while occassional miking of an Ampeg B-15 occurred later on, it served as Jamerson’s live sound throughout his rumble king reign.

Hearing his living, breathing tone up close on the original master tapes of such gems as The Four Tops’ “Bernadette,” Steve Wonder’s “I Was Made to Love Her,” and Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” in the Motown vault, as BP got to do for the Dec. ’09 issue, is nothing short of a revelation.

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Bass ’62 Fender Precision “Funk Machine”

Rig Ampeg B-15

Strings LaBella flatwounds (.052–.110)

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Marvin Gaye, What’s Going On [Motown, 1971]

*The Complete Motown #1s Box [Motown, 2008]

Standing in the Shadows of Motown: Deluxe Edition [Hip-O, 2004]

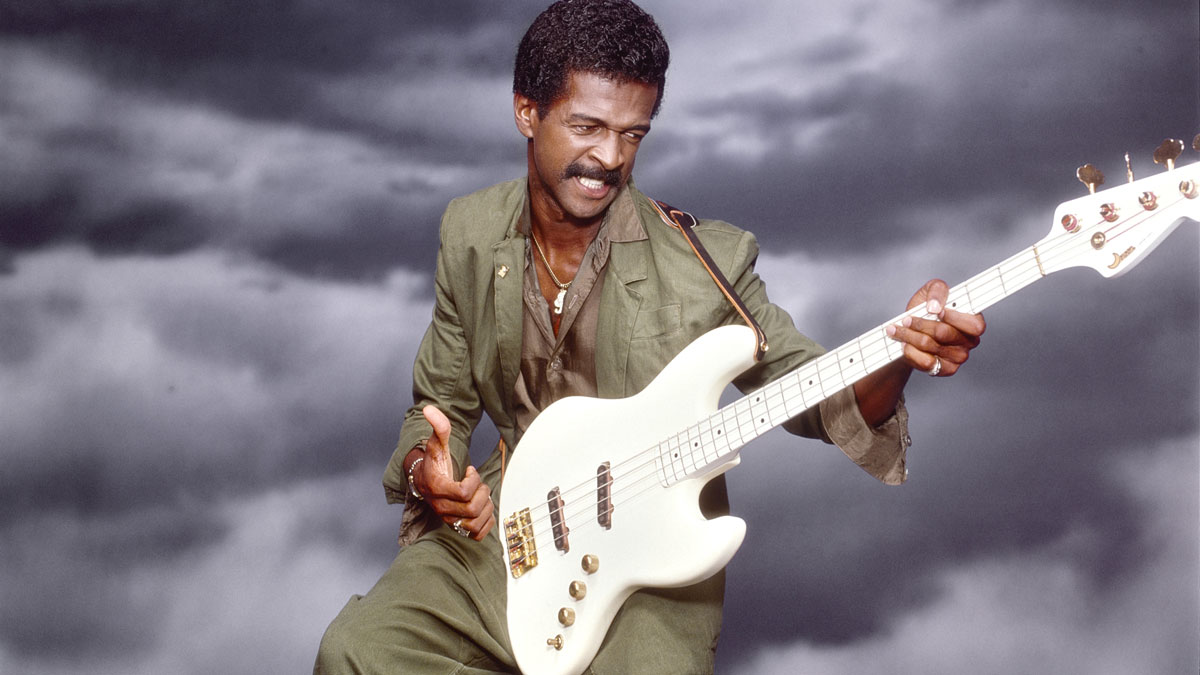

11. Louis Johnson

Slappers can argue until they’re blue in the face about the origin of the now near ubiquitous funk playing style, but in fact it seems to be a case of convergent evolution: Louis Johnson had never heard of fellow slap pioneer Graham when he began to develop his signature style, inspired by the mariachi guitarrón players in his native Los Angeles.

One thing is for certain: “Thunder Thumbs” Johnson’s scooped tone and killer chops are in full effect on tracks as varied as Michael McDonald’s “I Keep Forgettin’,” Michael Jackson’s “Don’t Stop ‘Till You Get Enough,” and any number of tracks with the Brothers Johnson.

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Bass MusicMan StingRay

Rig Fender Bassman

Strings D’Addario roundwounds

ESSENTIAL SIDES

The Brothers Johnson, Right On Time [A&M, 1977]

The Brothers Johnson, Light Up The Night [A&M, 1980]

Michael Jackson, Thriller [Epic, 1982]

12. John Paul Jones

From the woolen Fender P-Bass tones of his early days in Led Zeppelin to later experiments with hi-fi 8- and 10-string basses, John Paul Jones established himself early on as an intrepid tone explorer with a knack for finding the sweet spot between old-school and new-fangled.

An early adopter of roundwound Rotosound strings, Jones didn’t go quite so far down the bright path as his peers John Entwistle and Chris Squire, opting rather for a more mellow, supportive sound.

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses 1963 Fender Jazz Bass, ’52 Fender Precision Bass, 8- and 10-string Alembic, Hagstrom, and Manson basses

Rig Acoustic 360, Teddy Wallace 30-watt 2x12 combo

Strings Rotosound

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Led Zeppelin, Led Zeppelin II [Atlantic, 1969]

Led Zeppelin, Houses of the Holy [Atlantic, 1973]

Led Zeppelin, Physical Graffiti [Swan Song, 1975]

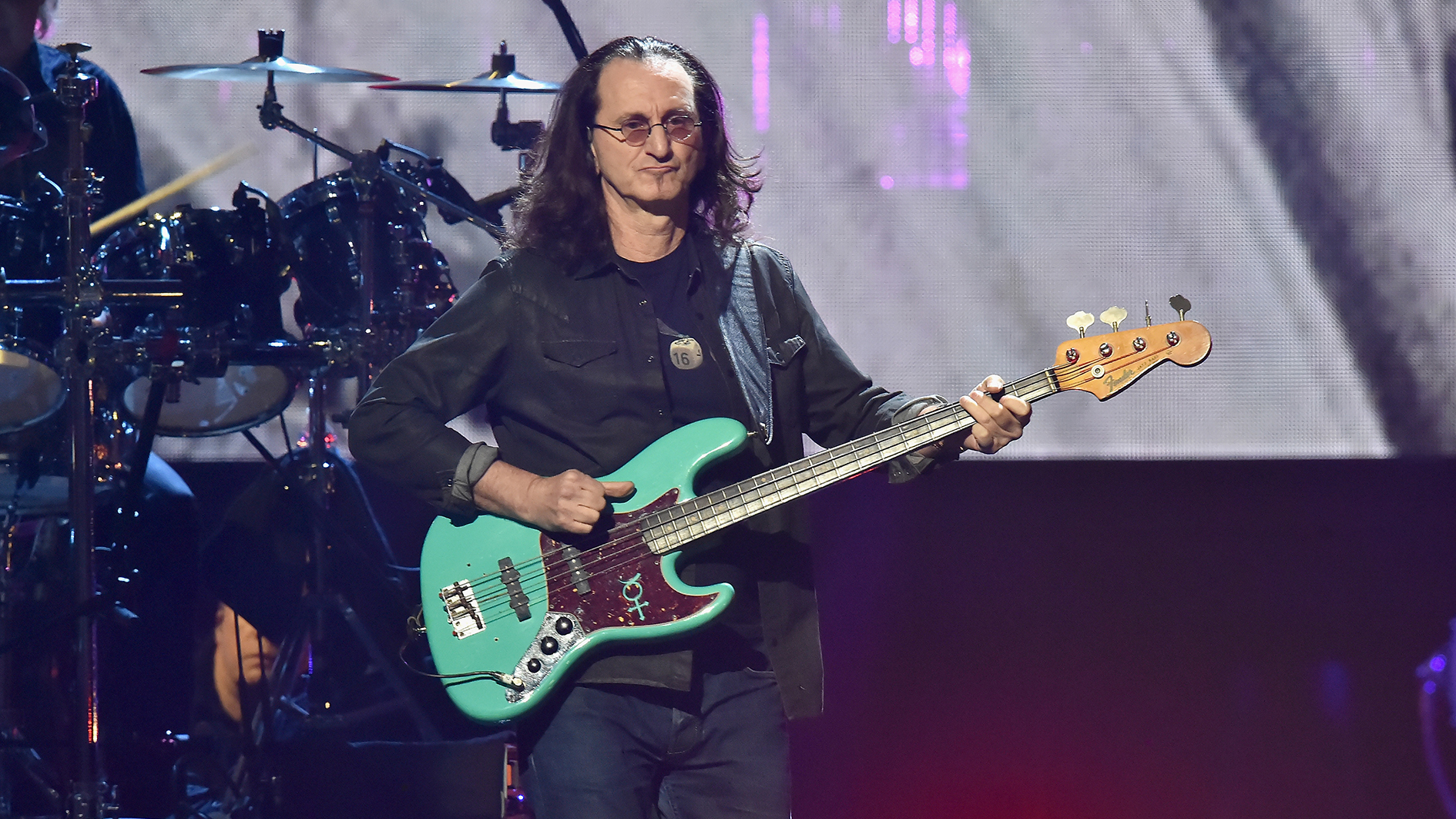

13. Geddy Lee

“I’m a fairly obnoxious bass player,” the Rush frontman flatly told Bass Player in August 2007.

Though fans might be taken aback by such a frank assessment, we’re inclined to trust Geddy’s judgement—he’s crafted an instantly identifiable tone over the years (on record, mostly courtesy a 1972 Fender Jazz Bass), and whether he’s clanging away on his Fender, a Rickenbacker, a Wal, or a Steinberg, the biting attack and acerbic grit of his tone always cuts through.

“In the early days, [my tone] was clangy top end first, with a round but not overly aggressive bottom end.” Geddy explained to BP in March 2006. “In the mid ’80s I started crunching it up a bit more with distortion and compression. It’s continued to change with every record.”

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses 1972 Fender Jazz Bass, Rickenbacker 4001

Rig Palmer PDI-05 Speaker Simulator, Orange AD200 heads and OBC410 cabinets

Strings Rotosound Swing Bass

Other Tech 21 SansAmp RBI

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Rush, 2112 [Mercury, 1976]

Rush, Permanent Waves [Mercury, 1980]

Rush, Moving Pictures [Mercury, 1981]

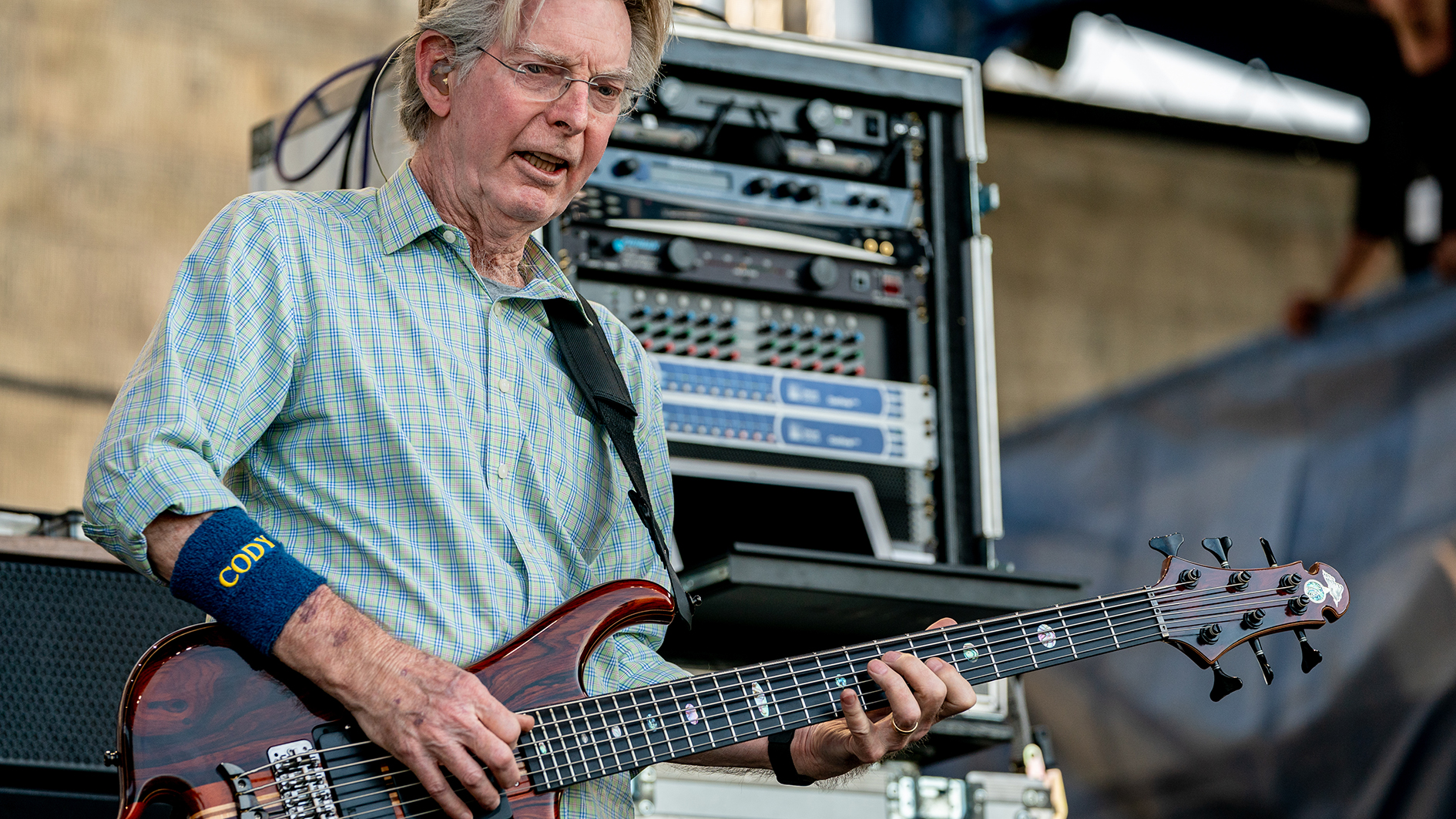

14. Phil Lesh

From his early experimentation with active electronics and the Grateful Dead’s colossal “Wall of Sound” PA system to his pioneering work on 6-string bass, Phil Lesh has left a mark on the technology of tone as deep and broad as his band’s headiest jams.

After teaming up with electronics wiz Ron Wickersham in 1968, Phil—along with Jefferson Airplane bassist Jack Casady—was one of the first players to wield an electric bass with active electronics. “I wanted to be able to boost any area of the frequency spectrum,” Phil told Bass Player in July 2000. “But most of all, I wanted the tone to be consistent across the instrument’s whole range.”

The Dead’s fabled Wall of Sound, a massive vertical array of speakers the band began to tour with in 1972, was a revolutionary approach to live sound reproduction in which Lesh was allotted no fewer than 32 speakers.

“I had two bass speaker columns, each 30 feet high.” Phil recalled. “I think there were 16 speakers in each column, so I had eight speakers for the E string, eight for the A, and so on.”

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses Guild Starfire with Alembic electronics, Modulus Quantum 6

Rig 32x10 custom Wall of Sound

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Grateful Dead, American Beauty [Warner Bros., 1970]

Grateful Dead, Grateful Dead [Warner Bros., 1971]

Grateful Dead, Europe ’72 [Warner Bros., 1972]

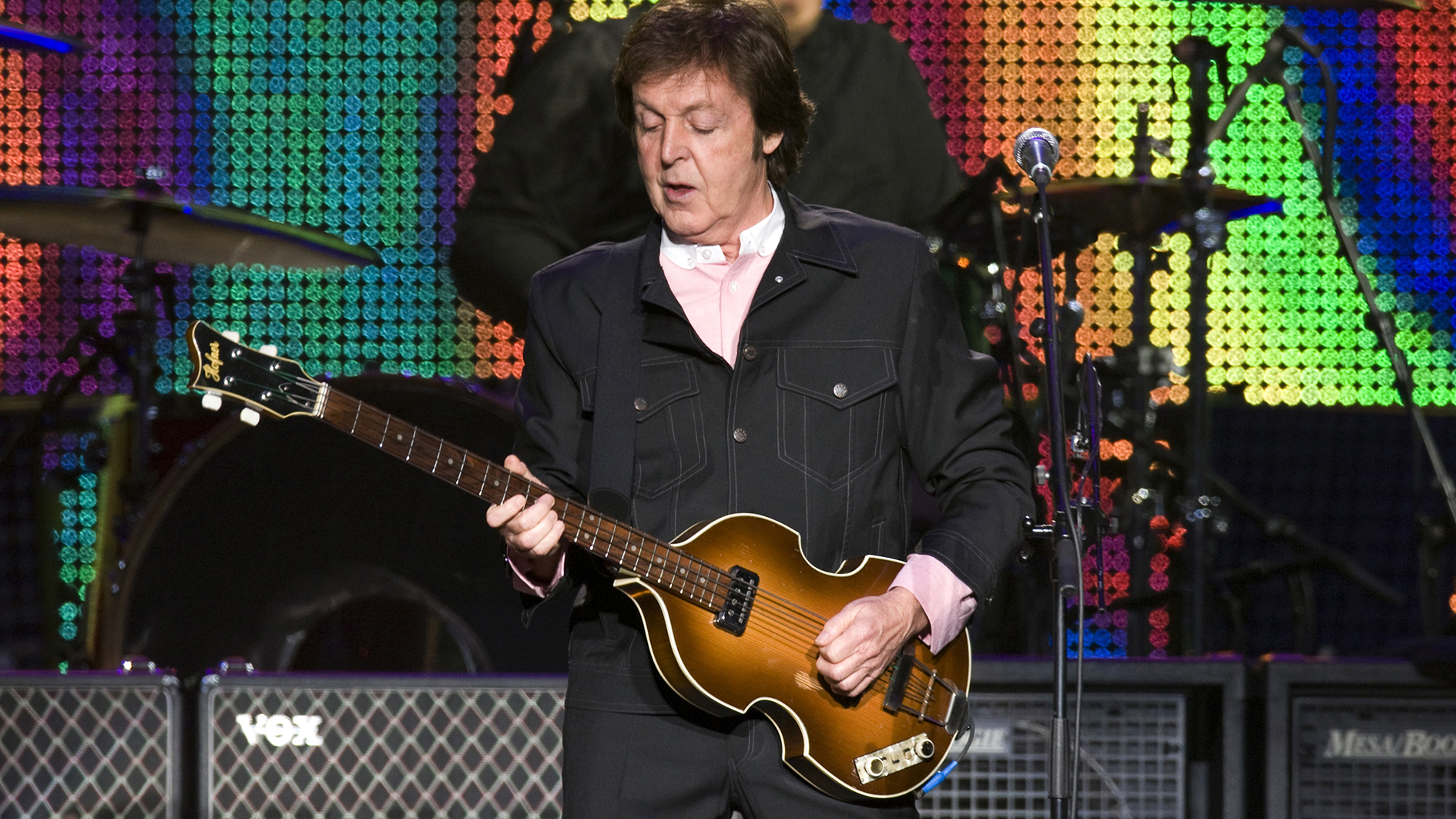

15. Paul McCartney

While the Beatles bass man’s low-end legacy will be forever tied to his melodic approach to the instrument, that very approach was informed by the plunky sounds he coaxed from his hollowbody Hofner 500/2 and the clarion tones he goaded from his Rickenbacker 4001S.

Though Sir Paul and the band were utterly overpowered by crowd noise during the heydey of the Beatles’ brief touring career—a major factor in the band’s decision to stop touring—McCartney’s bass presence on record was massive.

From wonderfully woofy and muted (“Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds”) to dark and edgy (“Hey Bulldog”), McCartney did for pop bass what James Jamerson did for R&B and Jaco Pastorius did for jazz fusion.

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses 1963 Hofner 500/1, ’65 Rickenbacker 4001S

Rig Mesa Boogie Bass 400+ head and Mesa Super 15 and 1516 cabinets

Strings La Bella flatwounds (.039–.096)

ESSENTIAL SIDES

The Beatles, Rubber Soul [Capitol, 1969]

The Beatles, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band [Capitol, 1967]

Paul McCartney & Wings, Band on the Run [Apple, 1973]

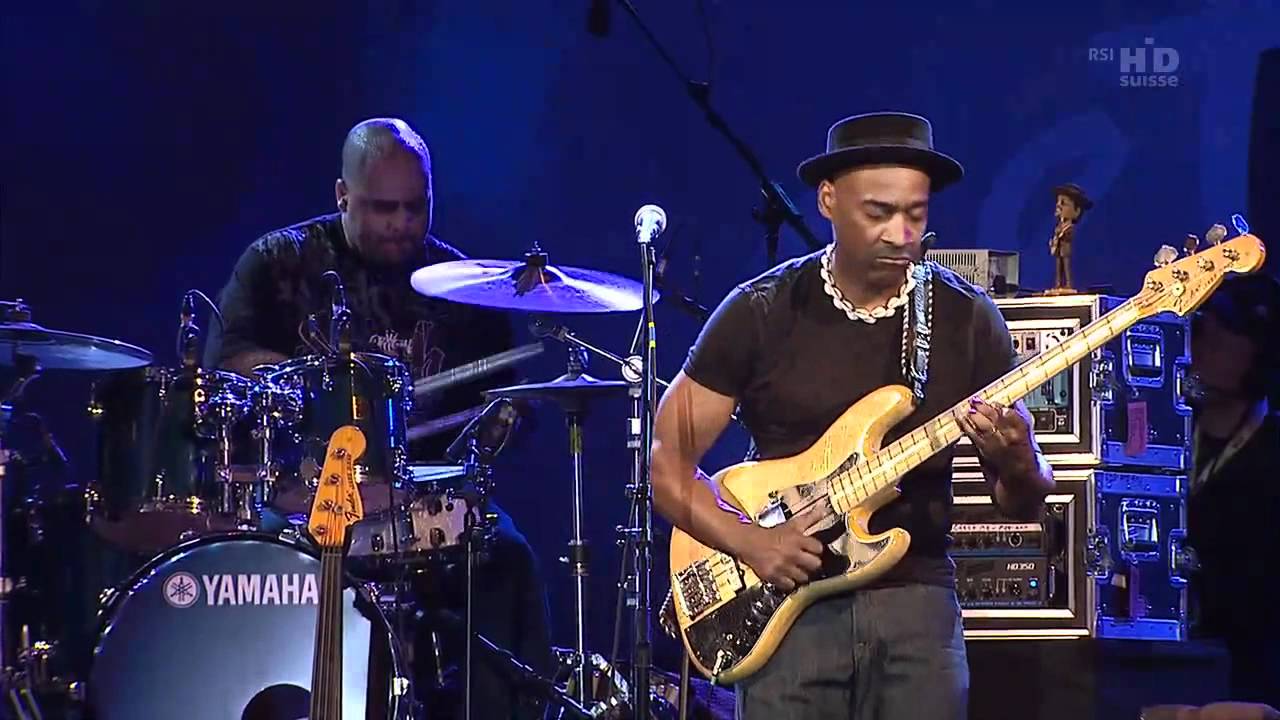

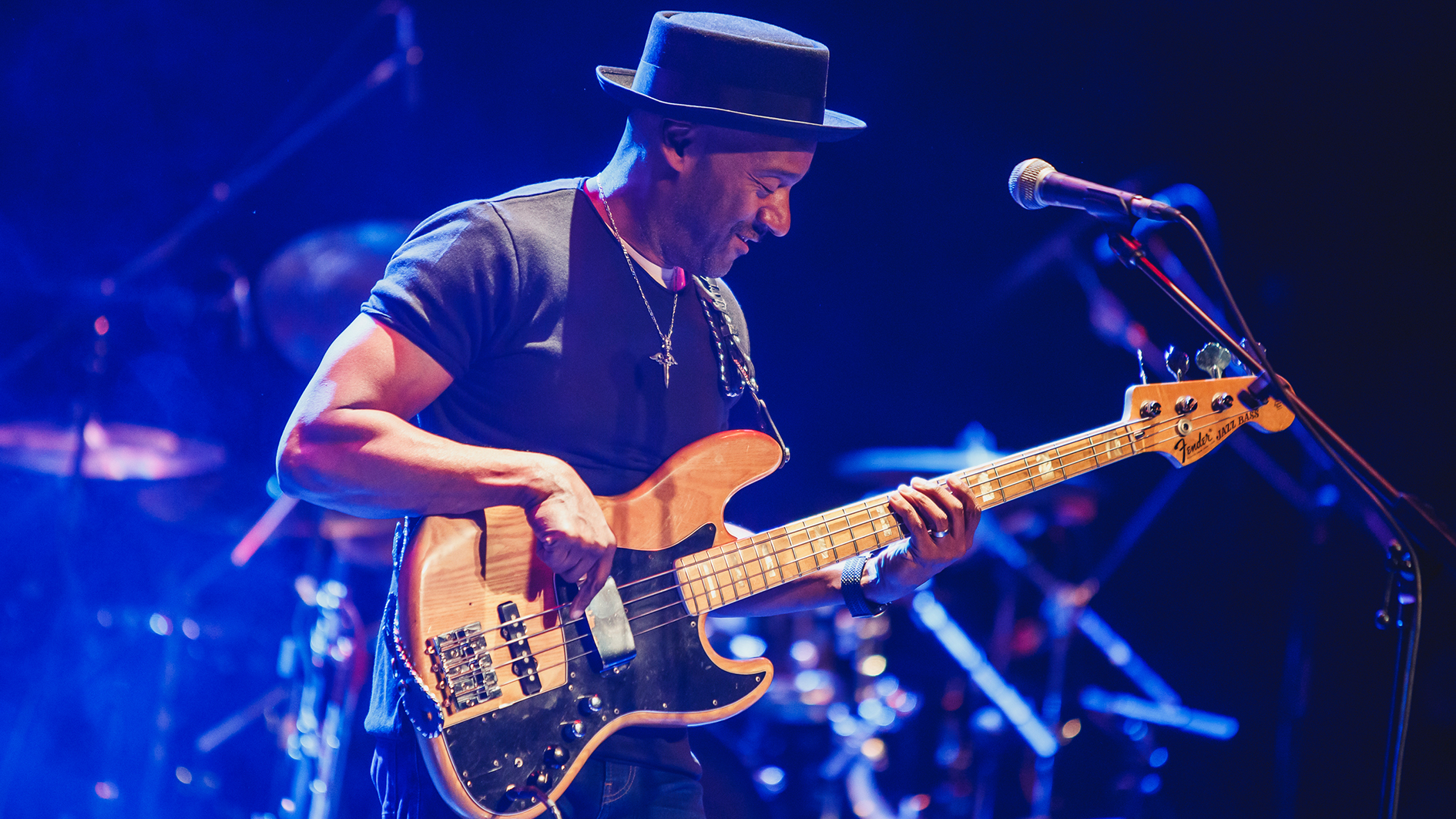

16. Marcus Miller

In the late-’70s, the Fender Jazz Bass, slapping, and the ability to boost highs and lows already existed. But when Marcus Miller combined those ingredients with his profound musical gifts he forged one of the most admired, desired, and imitated electric bass sounds in the 60-year history of the instrument.

Miller’s famed ’77 J-Bass wasn’t a highly regarded vintage when he got it as a teen; it was thought to be too heavy, with too much finish, a three-bolt neck, and a new back pickup position.

Within a few years and via the added help of a Sadowsky-installed preamp, Miller’s tone was carving out considerable space on jazz sides by Miles Davis and David Sanborn and pop hits by Luther Vandross and Grover Washington, Jr. (“Just the Two of Us”).

By the time he began his string of acclaimed instrumental albums in the ’90s, the “Marcus Miller sound” was as familiar as the “Jaco sound.” Miller generally kept his bass wide open, while his preamp provided a “steroid” boost to the lows and highs without sounding too electronic—thereby allowing the true tone of the Jazz Bass to remain.

The result was a round, clear, full-range sound marked by thick, punchy lows, defined mids, and bright, glassy high end. Of course, like Jaco, there were other essential elements—namely Miller’s unrivaled pocket depth and freefl owing phrasing borrowed heavily from vocalists and horn players.

Much of Miller’s sound was forged under headphones as a N.Y. studio ace, which he recalled in his BP October ’92 cover story.

“I was pretty young when I started doing sessions, so when the engineers would plug me into a direct box and ask for full volume, I’d turn the knobs on my Jazz Bass all the way up, and that became a key to my sound.”

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses ’77 Fender Jazz Bass; Fender Marcus Miller Jazz Bass

Rig SWR Marcus Miller Preamp and Golight 4x10 cabinets

Strings DR Marcus Miller Signature Fat Beams

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Miles Davis, Tutu [Warner Bros., 1986]

Marcus Miller, The Sun Don’t Lie [PRA, 1993]

Marcus Miller, M2 [Telarc, 2001]

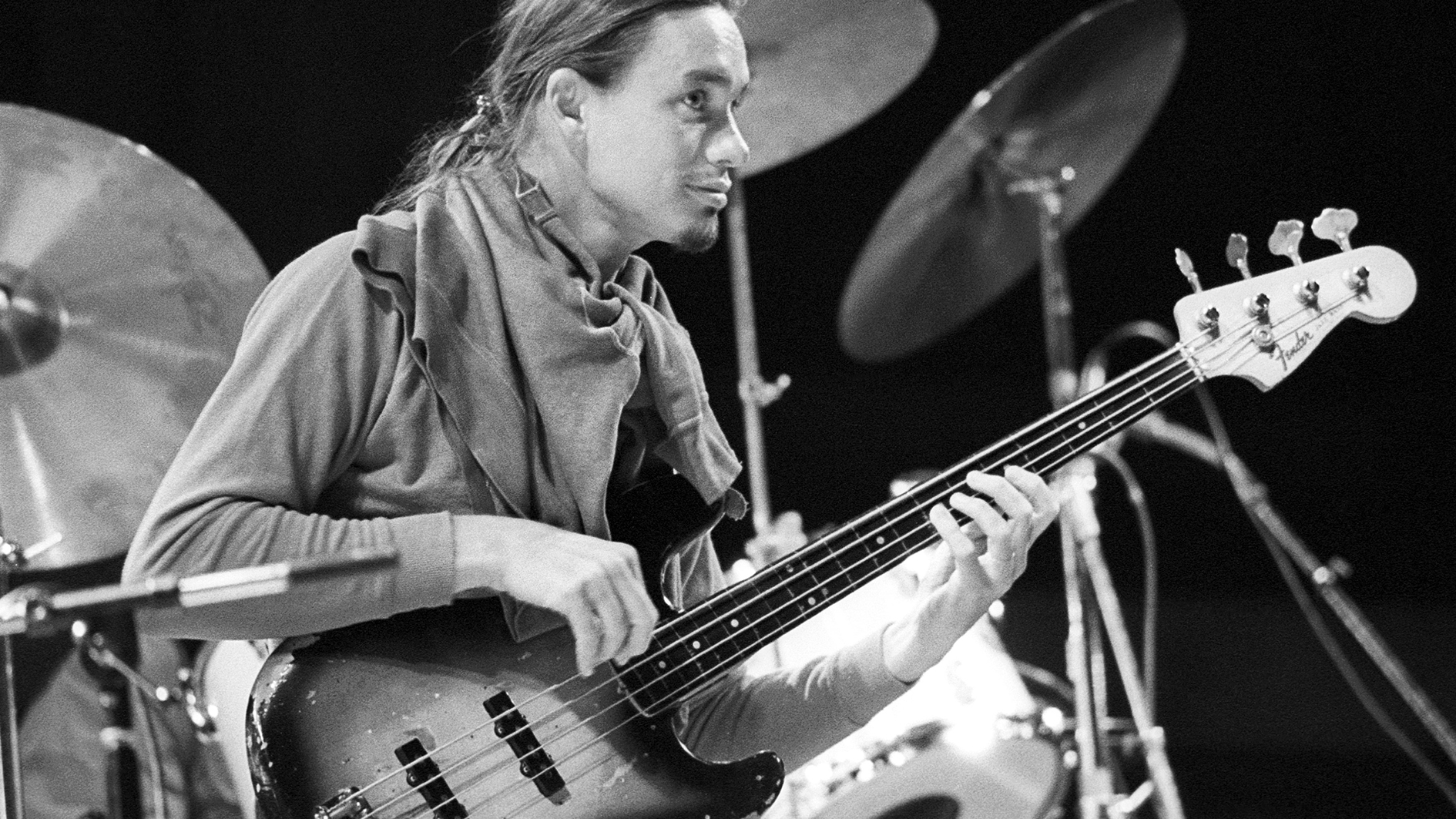

17. Jaco Pastorius

It’s impossible to spell the words “bass tone” without the letters J-A-C-O. Who knew that a fretless ’62 Fender Jazz Bass could yield cello-like sustain and vibrato, bell-clear natural and false harmonics, lush chords, percussive woops, deep, penetrating grooves, and poignant melodies? Jaco Pastorius knew.

After all, the sound, as he said, was “in his hands.” It has also been in the ears of the all of the rest of us, as Pastorius remains the all-pervasive infl uence on the instrument, especially when it comes to tone and thinking outside the fingerboard box.

The formula is pretty simple for such landscape-changing results: extra coats of Petite’s Poly-Poxy on his fretless board, for his trademark “mwah” sound; the neck pickup backed off to varying degrees, while plucking back near the bridge, where the strings are taut, for his signature cutting growl; and practice, practice, practice—okay, it also helps to be a musical genius with an unbelievable feel.

Whether he was helping to trailblaze jazz with Weather Report or pop with Joni Mitchell, or fronting a big band on his own epic discs, Jaco’s tone and touch were front and center and bass was never the same again.

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses ’62 fretless Fender Jazz “Bass of Doom”; ’60 fretted Fender Jazz Bass

Rig Two Acoustic 360’s (the second one for his chorus/flange signal)

Strings Rotosound Effects Fuzz tone from his Acoustic 360; MXR Digital Delay; Electro-Harmonix 16-second Digital Delay

Other Double-tracking or rack effects for chorusing in the studio

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Jaco Pastorius, Jaco Pastorius [Columbia, 1976]

Weather Report, Heavy Weather [Columbia, 1977]

Jaco Pastorius, Word of Mouth [Warner Bros., 1981]

18. Francis “Rocco” Prestia

He possesses perhaps the most individual, inimitable tone in the bass spectrum, but if you want to play finger-funk with that much precision and propulsion you better shorten your notes like the Tower Of Power groove legend.

Prestia accomplishes his muting mastery primarily with his left hand (although staccato plucking with his alternating right index and middle fingers is a key part of the formula). He lays his left hand in one four-fret position on the fingerboard, fingering the notes mostly with his index and middle fingers, while his ring finger and pinky dampen the strings.

What follows is an instinctually hip, alternating stream of pitches (fretted notes), deadened notes (in which he frets the note but only a thud sounds) and ghosted notes (in which he lightly mutes a string, without pressing it down on a fret). The reverse P-Bass pickup on all of his instruments and the warmth and depth of an amp also figure into his pop and punch.

In his December ’97 BP cover story, Rocco explained how he first arrived at his signature throb thanks to instant chemistry with T.O.P. drummer David Garibaldi.

“Dave was really busy, and I came from a more simple, laidback R&B bag. We met in the middle and refined our concept from there. At some point I realized that more staccato and percussive playing seemed to lock better with the drums. Short notes are still the way I hear the groove.”

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses Signature Conklin Groove Tools GTRP-4, Fender Precision Bass

Rig T.C. Electronics Staccato ’51 head, RS410 and RS212 cabinets

Strings Dean Markley Rocco Prestia NPS Roundcore Bass

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Tower Of Power, Tower of Power [Warner Bros., 1973]

Tower Of Power, Back to Oakland [Warner Bros., 1974]

Rocco Prestia, Everybody on the Bus [Lightyear, 1999]

19. Chris Squire

“When I became famous with tunes like “Roundabout” [Yes, Fragile] lots of guys ran out to buy Rickenbackers to sound like me,” Chris Squire told BP in January 2009.”But they didn’t always get rewarded with the same kind of sound.”

With its gritty, clacky attack, that signature Squire sound comes courtesy of Chris’s aggressive pickstyle approach, roundwound Rotosound strings, and a Rickenbacker wired in stereo, with separate outputs for each pickup.

“I loved the fuzz tone I could get from the bass [neck] pickup,” says Chris. “But with the bridge pickup, the fuzz was horribly nasal sounding. All of my guitars have stereo outputs for that reason. With new innovations through the years, these little nuances have come into play and been part of my development.”

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses 1964 Rickenbacker 4001

Rig Marshall Super Bass head

Strings Rotosound

Other Dutron and Moog Taurus bass pedals

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Yes, Fragile [Atlantic, 1972]

Yes, Yessongs [Atlantic, 1973]

Chris Squire, Fish Out of Water [Atlantic, 1975]

20. Victor Wooten

Given the game-changing impact Victor Wooten has had on the musical and technical sides of bassdom, one might overlook the tonal implications. But Victa’s tight, focused, Fodera-borne neck-through-body sound is as much a part of his sonic signature as his double-thumb slaps, terrifying taps, and deep pocket apps. It’s also one of the most sought after by Wooten wanna-bes.

Developed from a wide array of influences, including his brothers, Stanley Clarke, the Gap Band’s Robert Wilson, and the cello, Victor’s tone comes in various shades: bright and overtone-rich for his chordal, slapping and tapping work, darker and pointed for his plucked and muted support side, and always with a clarity to best capture each and every note, from furious flourishes to fundamental.

In his BP October 2003 cover story, Wooten revealed a simple little tip that helped tame his tone.

“I put a ponytail holder around the neck of my bass, just in front of the nut, to clean up some of the ringing. I’ve also been experimenting with it. If you slide it halfway up the fingerboard, like a capo, you can still play normal notes above it—but behind it you get these weird dead notes that bring out a different timbre of the instrument.”

ESSENTIAL GEAR

Basses ’83 Fodera Monarch, Monarch tenor, and signature Yin Yang basses, Compito fretless 5

Rig Hartke LH1000 head, Hydrive HX410 and Hx115 cabinets

Strings Fodera Victor Wooten Nickel Roundwounds

Other Boss GT-6B Bass Effects Processor

ESSENTIAL SIDES

Bela Fleck & the Flecktones, Bela Fleck & the Flecktones [Warner Bros., 1990]

Victor Wooten, A Show of Hands [Compass, 1996/2011]

Victor Wooten, Soul Circus, [Vanguard, 2005]

Bass Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful bass publication for passionate bassists and active musicians of all ages. Whatever your ability, BP has the interviews, reviews and lessons that will make you a better bass player. We go behind the scenes with bass manufacturers, ask a stellar crew of bass players for their advice, and bring you insights into pretty much every style of bass playing that exists, from reggae to jazz to metal and beyond. The gear we review ranges from the affordable to the upmarket and we maximise the opportunity to evolve our playing with the best teachers on the planet.

“When I first heard his voice in my headphones, there was that moment of, ‘My God! I’m recording with David Bowie!’” Bassist Tim Lefebvre on the making of David Bowie's Lazarus

“One of the guys said, ‘Joni, there’s this weird bass player in Florida, you’d probably like him’”: How Joni Mitchell formed an unlikely partnership with Jaco Pastorius