Zakk Wylde and Ozzy Osbourne Revisit 1988's 'No Rest for the Wicked'

This story originally appeared in the February 2014 issue of Guitar World.

In the pantheon of Ozzy Osbourne solo albums, 1988’s No Rest for the Wicked is neither trailblazing like the Randy Rhoads-assisted Blizzard of Ozz and Diary of a Madman nor a high-water mark like the four-times-Platinum-selling No More Tears.

It hasn’t even stood the test of time all that well: although No Rest for the Wicked moved more than a million copies in its first six months of release and was Osbourne’s second-highest charting solo effort up to that point, its songs—including hit singles like “Crazy Babies” and “Miracle Man”—are rarely, if ever, played live by the man today (though in recent years he has resurrected the power ballad “Fire in the Sky” at select shows).

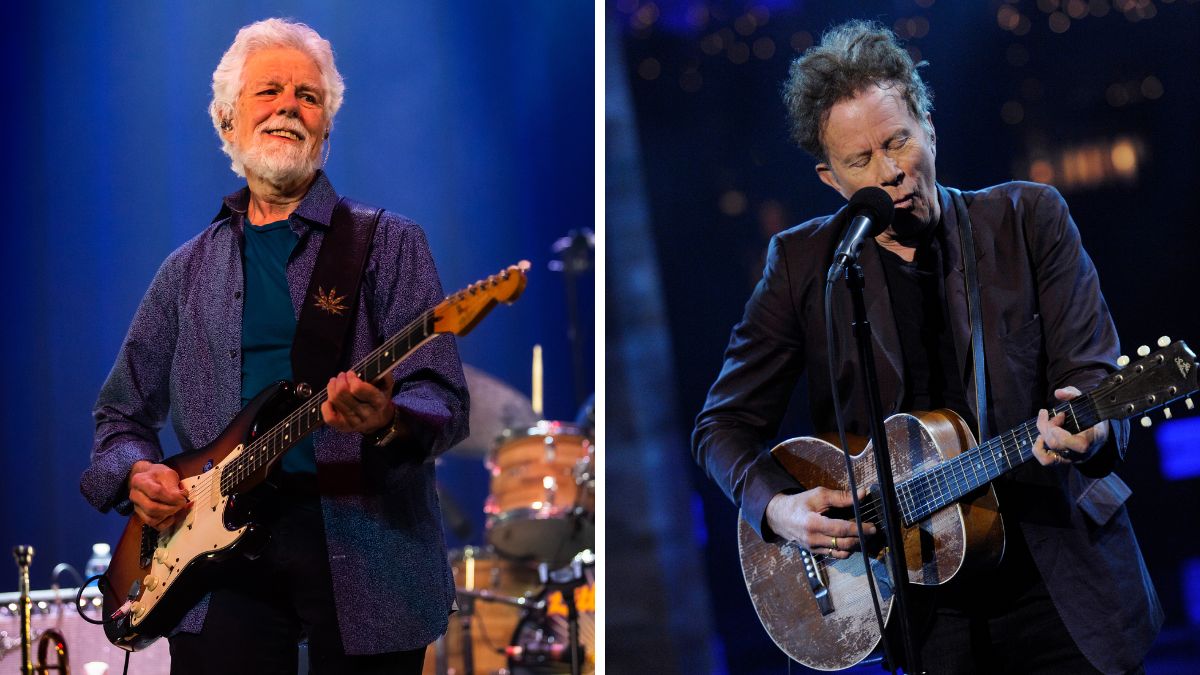

But No Rest for the Wicked will forever stand as an essential entry in the Ozzy Osbourne catalog for one very significant reason: it presented to the metal world the debut of a young guitar phenom by the name of Zakk Wylde.

Just 21 years old at the time of the album’s release, Wylde would go on to serve as Osbourne’s right-hand man for many years to come and grow into one of the most dynamic, influential and respected guitar players in modern hard rock and metal.

“He’s a fucking absolutely amazing guitar player,” Osbourne says of Wylde today, speaking to Guitar World from his home in Los Angeles. “And from the word go, he was great. He don’t fuck around. He hits it right in the fucking gut.”

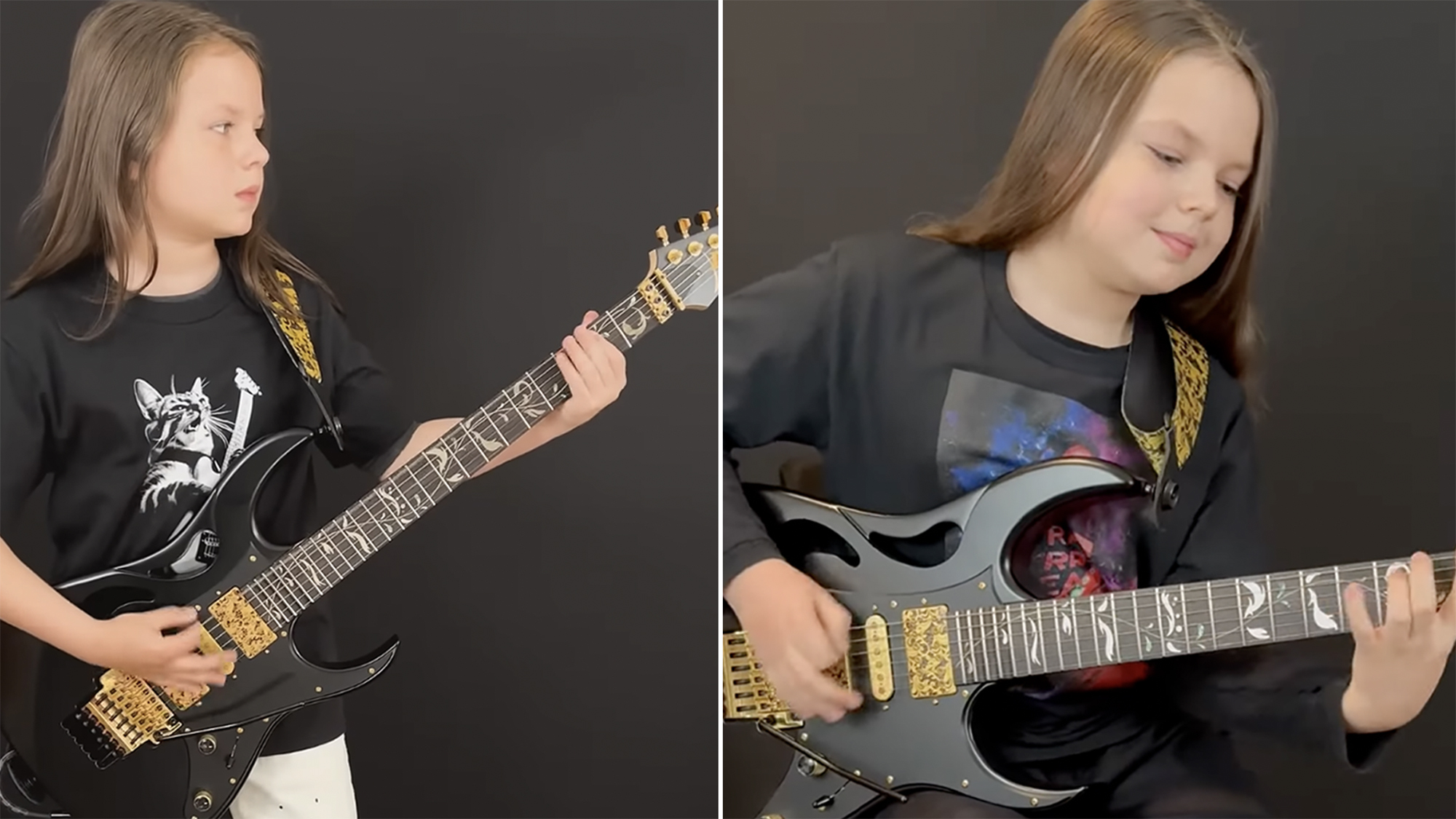

And yet, back in 1987, Wylde—or, make that, Jeffrey Wielandt—was merely one among thousands of big-haired, big-riffing metal guitarists honing their craft in small-town bars and clubs across the U.S. At the time, the New Jersey native spent his days pumping gas at a service station and giving guitar lessons, and his nights playing in a local act named Zyris that had built up a strong area following. Wylde was also, as he has attested often over the years, a huge Ozzy and Black Sabbath fan. “I loved Sabbath, loved Randy, and I thought Jake [E. Lee] was great, too,” the guitarist, now 46, recalls.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“And I remember around that time [in 1987] hearing Ozz on The Howard Stern Show. Jake was gone and he was looking for a new guy. And Barb [Wylde’s then-girlfriend, and now wife, Barbaranne] said to me, ‘If you could just get a tape to him…’ And it was like, ‘Yeah, sure. How am I gonna do that?’ ” The answer to that question came just a few weeks later, after a Zyris performance at Close Encounters, a club in Sayreville, New Jersey.

“It was a Saturday night gig, in front of, I don’t know, maybe 108 people,” Wylde says with a laugh. “Nothing too spectacular. And afterward, I’m loading up my gear and this guy named Dave Feld comes up to me and says, ‘Have you ever thought about auditioning for Ozzy?’ And I’m like, ‘Sure, whatever dude. You know the guys from Zeppelin, too?’ But he told me if I put together a demo tape and took some pictures he could get it to a friend of his, [photographer] Mark Weiss, who had just finished doing a shoot with Ozzy.” Though Feld would later work for Atlantic Records—according to Wylde, he was responsible for pairing another New Jersey band, Skid Row, with singer Sebastian Bach—at the time he was merely a local acquaintance of the guitarist’s.

“Dave said, ‘I can’t promise you anything, but it’s a shot,’ ” Wylde continues.

“So I figured, Why the hell not?” For his audition tape, which over the years has cropped up in various configurations online, Wylde compiled a few original riffs and solos, as well as some acoustic classical performances and his interpretations of Rhoads’ leads from the Blizzard of Ozz classic “Mr. Crowley” and Diary of a Madman’s “Flying High Again.”

Even at this young age, Wylde’s playing, despite some era-appropriate pop-metal and neoclassical moments in the original material, sounds remarkably similar to his style today, full of incredibly speedy and precise alternate-picked passages and wide, vocal-like note vibrato. The quality of the recording, however, did not match that of the playing.

“I think I had two boomboxes going,” Wylde recalls. “I recorded myself doing the rhythms on one, then played that back and soloed along with it and recorded that on the other one. It was early multitracking.” But Feld did in fact make good on getting the tape, via Mark Weiss, to Ozzy’s camp. In time, Wylde received a call at his parents’ house from Osbourne’s wife and manager, Sharon, asking him to come out to L.A.

“The running joke was that it was one of my jackoff friends putting his mom on the phone to fuck with me,” Wylde says. “But then they sent me a plane ticket.” Wylde was one of several hopefuls, out of a pool of what has been reported to have been more than 400, to receive an invite to audition. He recalls arriving at an old rehearsal space off of Lankershim Boulevard in Los Angeles. “I walk into the room, and here I am, first time ever in L.A., and I’m meeting Ozzy Osbourne. And Ozz comes in and—I’ll never forget it—he goes, ‘Have I met you before?’ ” Osbourne, of course, had not, though he had in fact seen Wylde.

“You can only imagine how many fucking tapes and photos we got when I was looking for a guitar player,” Osbourne says. “And the only one I remember even picking up, oddly enough, was Zakk’s. And he had this picture on it, and I said, ‘Oh, a Randy Rhoads clone! And I tossed it aside. You see him now and he looks like a member of the fucking Taliban! But then he was very clean cut, with big, blonde hair. A boy.”

A boy, perhaps, but certainly not one of Rhoads’ diminutive stature. Says Wylde, “I remember one time early on Ozz just looking at me, and I’m a good six feet tall, and he just goes, ‘Well, fuck that. There’s no way I’m gonna try to pick you up like Randy!’ ” He continues.

“But people always ask me, ‘What did Ozzy say to you before you actually played? What was that like? And this is the truth. He said, ‘Zakk, all I want you to do is play from your fucking heart.’ Then, afterward: ‘Change your trousers. ’Cause you stink. Also, make me a ham sandwich. And go light on the mustard!’ ” According to Wylde, his audition also included drummer Randy Castillo and bassist Phil Soussan, both of whom had performed, along with Jake E. Lee, on 1986’s The Ultimate Sin. Among the songs he played were “Suicide Solution,” “Bark at the Moon” and “Crazy Train.”

“The mandatory tunes,” he says. In the end it came down to Wylde and one other candidate, a guitarist named Jimi Bell who had worked previously with Joan Jett (Bell would go on to play with Geezer Butler’s solo band and, more recently, design the Shredneck guitar practice tool). And though Wylde says he didn’t have much contact with the other players vying for the spot, he also knew it was his to lose.

“I remember when I was out there auditioning, they put everyone up at the Hyatt on Sunset. And some of the guys there were talking about how well the gig pays, this and that. They weren’t really Ozzy or Sabbath fans. They could give a shit. The analogy I always use is they just wanted to play for the Yankees, you know? Because that’s where the money was. Whereas I had every picture of every Yankee up on my wall, and knew everybody’s batting average.

To me, the pinstripes were a sacred fucking thing. So I thought, Fuck these clowns. I’m gonna get this fucking gig.” Wylde did get the gig and soon enough was shipped off to England with the rest of the band to begin writing the songs that would become No Rest for the Wicked.. The group holed up at what Wylde recalls as an “old horse stable near Brighton that had been converted into living quarters and a rehearsal space.” The best thing about it? “The pub was walking distance, just down the road,” he says. “Ten in the morning, Ozz would be there having cocktails, and then, after jamming all day, we’d all close it out at night.”

From England, the band relocated to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where writing sessions continued. By this time, bassist Soussan had exited the group, and longtime Osbourne associate Bob Daisley, who performed on Blizzard of Ozz, Diary of a Madman and Bark at the Moon, returned to the fold. On record, the new music that they were composing—evidenced on stomping, groove-heavy songs like “Crazy Babies” and “Breaking All the Rules,” and the rampaging “Miracle Man” (which also featured the first riff Wylde wrote as a member of the band)—proved to be thicker and heavier than anything Ozzy had done in recent years.

This change was partly a result of Wylde’s aggressive playing style and ballsy, Les Paul–led attack. But it also had something to do with what Ozzy saw as deficiencies in the sound of his previous album. “The reason why No Rest for the Wicked. became a heavier album for me is because when we did The Ultimate Sin with [producer] Ron Nevison, I got the impression he didn’t really put anything into it,” Osbourne says. “Every track to me sounded very similar. And it was not my favorite kind of sound.” And yet, the initial No Rest sessions, which took place with legendary Queen producer Roy Thomas Baker at Enterprise Studios in Burbank, California, offered up similarly underwhelming results.

“I had a lot of problems with Roy, too,” Osbourne says. “Somebody else had to repair the album, because he had done a bad fucking job.” Says Wylde, “When we first went into the studio, I remember being so excited, like, ‘Wow, we’re working with Roy Thomas Baker! He worked with Brian May!’ I was thinking that this was where all the magic was gonna happen. But pretty early on, I knew that wasn’t going to be the case. There was one time I was listening back to some guitar tracks, and I said to Roy, ‘Dude, we need more meat on my guitar tone.’ And I remember he turns to me and goes, ‘Well, Zakk, hit the “meat” knob.’ That was it! So, needless to say, it didn’t pan out with Roy.”

From there, things only went from bad to worse. “At the end, we got the tapes back, and it didn’t sound like a record,” Wylde continues. “It didn’t sound like the real deal. And I remember saying to Mom [Wylde’s nickname for Sharon Osbourne], ‘It just doesn’t sound good. Do you think Roy would let me redo the guitars?’ And she said, ‘Ask him.’ And I go in there and I’m shitting my pants because I’m all of 20, 21 years old. But I say, ‘Um, Roy could I ask you ask a question? Do you think we could redo my guitars?’ And he says, ‘Yeah. On what song?’ And I go, ‘All of them.’ And there was a pause. Roy was tapping a pencil on the console. And all of a sudden he throws it up and it sticks into the ceiling. He gets up, grabs his briefcase and just storms the fuck off. And the engineer is sitting there shaking his head, and he goes, ‘You shouldn’t have said that…’ ”

Needless to say, Osbourne eventually severed ties with Baker. The band then hooked up with producer Keith Olsen, best known for his work with Fleetwood Mac, and reconvened at his studio, Goodnight L.A. Says Zakk, “When Keith came in, he saved the fucking day.”

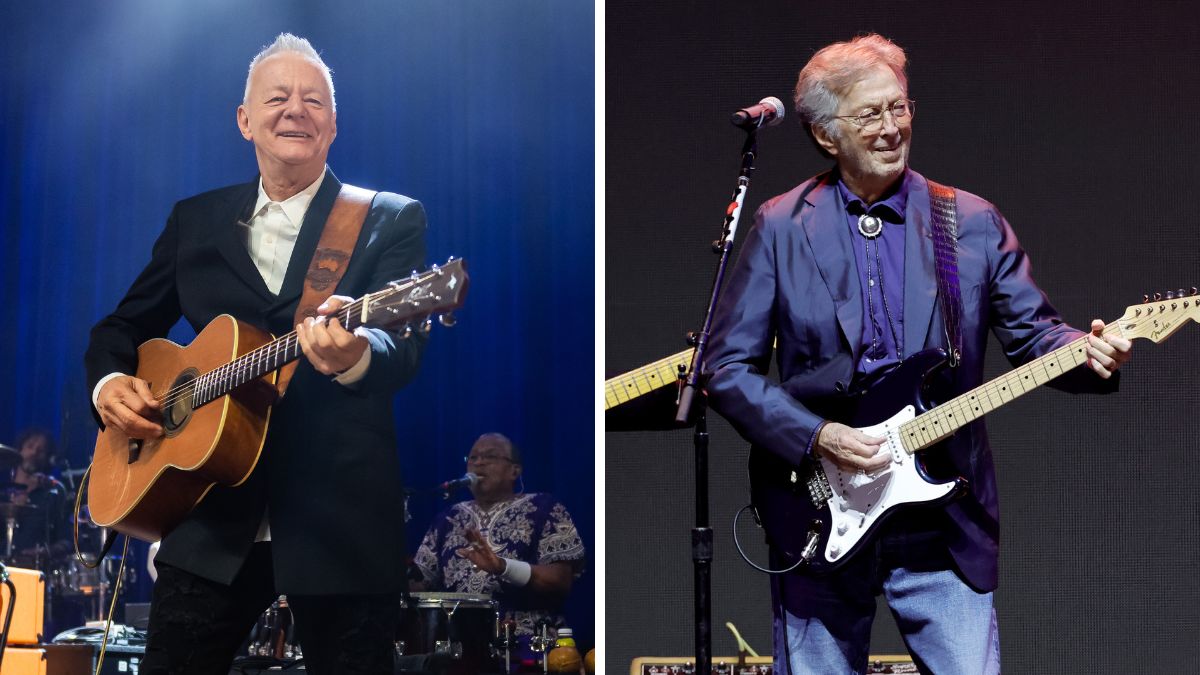

Olsen also saved Wylde’s guitar tone. At Enterprise Studios, Wylde, who had tracked his parts using Lee Jackson Metaltronix amps, had been frustrated with his overall sound. At Goodnight L.A., he recalls, “I was talking to Keith about what I wanted from my tone, and I played him TNT’s ‘10,000 Lovers (In One).’ I was like, ‘Listen to Ronni Le Tekro’s fucking guitar!’ I had the Grail [Wylde’s 1981 original bull’s-eye Les Paul, with EMG 81 and 85 pickups], and Keith said to me, ‘All right, Zakk, plug into this.’ And it was a [Marshall] JCM 800 combo amp—the same one John Sykes used on the Whitesnake record [which Olsen co-produced]. We ran a line out to a Marshall 4x12 cab, I threw in my Boss SD-1 [Super OverDrive] and double-tracked everything. It sounded huge, and that was it.” For Wylde, distinguishing himself from the heavy metal pack on what would be his recorded debut meant not only nailing the perfect tone but also finding his own voice when it came to the actual playing. He achieved this on his solos through a process of elimination.

“Guys like Yngwie were really big at that time, but I wanted to make sure I sounded like me,” Wylde says. “So I had my grocery list of shit I wasn’t going to do: Sweep picking—cross that off. Harmonic minor scales—cross those off. Diminished scales—off. Tapping—off. And then I said, ‘What’s left?’ And basically it was pentatonic scales. So I started there, and then I heard some of the country stuff, like chicken pickin’, and I thought, That’s bad ass. So I incorporated some of that shit into my playing, which you can hear on songs like ‘Crazy Babies’ and ‘Devil’s Daughter.’ ”

Adds Osbourne, “Zakk on that album did some fucking great solos. And what I admired about him was that he had worked the solos out. He didn’t just fill the gaps with a little fingertapping and fucking bullshit. I remember when he did the ‘Devil’s Daughter’ solo, I just thought it was awesome.

“But you know, I have a knack for finding great guitarists. Jake E. Lee, he was and still is a great guitar player. But it was just one of those things that happened. And Zakk would ask me questions about the previous guys, about Randy, about Jake, about Tony [Iommi]. He wanted to learn. And he only got better. People used to say to me, ‘Why don’t you go for the best soccer player?’ And I’d say, ‘No. I have more fun watching a guy who wants to be the best soccer player develop into him.’ Zakk was that guy.”

No Rest for the Wicked. was officially released as Osbourne’s fifth solo album on September 28, 1988, and a little less than two months later he and the band kicked off a U.S. arena tour, with openers Anthrax, in support of the effort. By this time, there had been some changes to the lineup. Bob Daisley had been replaced with Geezer Butler (meaning that Wylde now found himself playing songs like “Paranoid” and “Iron Man” alongside half of the original Black Sabbath). Furthermore, Zakk Wylde was now, well, Zakk Wylde. According to the guitarist, the development of his name had begun even before the Ozzy gig. “Back when I was still playing in bands in Jersey I had changed the spelling of my last name from Wielandt to Wylant, because no one could ever pronounce it,” he says.

“And then at one point, Barb had said to me, ‘If we have a kid someday, it’d be cool to name him Zack.’ So I just started using the name for myself! Then after I got the gig with Ozz, we were sitting around one time and he says to me, [adopts Ozzy voice] ‘Well, you gotta change your name. We can’t be playing Madison Square Garden and have it fucking say Ozzy Osbourne and Zack Wylant.’ So one night we’re hanging out, getting hammered, and a song by Kim Wilde, that hot British pop singer, comes on. And I said, ‘Fuck it, Ozz, what about Zakk Wylde?’ And he goes, ‘I like that. We’ll use that.’ ” Wylde laughs.

“Not only did I take my name from her, but if you look at some of my early photos, I probably stole her look, too!” As for the No Rest for the Wicked. tour, Wylde’s first full-scale outing, he recalls, “We were getting blasted and having a blast. Onstage, my pants would split and my balls would be hanging out as I played, or Ozzy would be hauling ass to the back during Randy’s drum solo because he had to take a huge shit. Afterward at the bars, we’d be pissing into pint glasses, seeing who could drink them the fastest. There’d be the goofiest shit going on all the time.” He laughs. “But at least no farm animals got hurt in the process.”

To this last statement, however, Wylde may not be entirely correct. At one point, the band headed to England to shoot a video for the album’s leadoff track, “Miracle Man.” In keeping with the lyrics of the song, which taunted the then-recently disgraced televangelist Jimmy Swaggart, a longtime outspoken critic of Osbourne’s, the group was filmed performing in an old church, with Ozzy surrounded by his own personal flock—dozens and dozens of pigs. A great concept, but one that produced an unexpected result.

“When the music went on, the pigs all took a massive shit at the same time,” Osbourne recalls. “Because it was so fucking loud in there. My wife went, ‘Oh, fuck!’ The playback started and they all went pfffffftttt! Sixty pigs shitting! I had a pair of brand-new suede boots on, and I never wore them again. I couldn’t get the fucking smell of pig shit out of them.” It should also be noted that playing to a roomful of pigs was not even Wylde’s first performance with Ozzy to take place in front of a less than traditional audience. His debut gig with Osbourne, just months after he joined the band, happened not in front of an arena full of rabid metal heads but rather at Wormwood Scrubs prison in West London, where they played a short, one-off set for inmates in July 1987.

“People always ask me, ‘Zakk, were you nervous for the first show?’ ” Wylde says. “Put it this way: I was clean shaven, 20 years old, weighed about a buck-fifty. I was the closest thing those guys were gonna see to Farrah Fawcett. So I was just thinking I best not fuck up. Because Ozzy might have left me in that jail.” By the time the No Rest for the Wicked. tour wrapped in August 1989—at a gig before more than 100,000 fans at the Moscow Music and Peace Festival in Russia—Wylde’s place in the band was firmly cemented. From there, the newly minted outfit took some time off before regrouping, once again with Daisley back in the fold, to write and record what would become 1991’s No More Tears. Featuring some of Ozzy’s most beloved songs, including the title track and the power ballad “Mama, I’m Coming Home,” Tears remains a creative and commercial high point for Osbourne in his solo career.

“It’s one of my favorites,” Osbourne says. “And the way I see it, No Rest for the Wicked. was kind of the developing album to get us to No More Tears. Every time I put a new band together, it gets to a certain point where you know each other and you’re sure of each other. After recording and touring together for a few years, Zakk and I were at that point. And everything fell into its right place.”

Wylde went on to record and tour with Ozzy throughout much of the Nineties and early 2000s, with a break during which he was replaced with Joe Holmes. And while he is currently fully devoted to leading his own unit, Black Label Society, and Osbourne is committed to his guitarist Gus G., in 2012 Wylde also joined his former boss as a guest on the Ozzy & Friends European tour. As for the possibility, 25 years after No Rest for the Wicked., of the two recording new music together, both men are open to it.

“Gus is a slamming guitar player, and it’s his gig,” Wylde says.

“But Ozzy knows I’m just a phone call away. If he needed anything I’d always be there for him.” Adds Osbourne, “I never say never anymore. Look, I thought I was never going to do another Black Sabbath album because it was getting on to a ridiculous time. But we did it, and it was Number One all over the place. So with Zakk, I’m not putting it out of the picture, and I’m sure he’s not either. If it’s meant to happen, it’ll happen. And we’re great friends. Our wives talk, the kids come over, he’s like a family member.”

“Our relationship is bigger than music,” Wylde concludes. “I mean, Ozzy’s the godfather of our oldest boy. If he called me up and said, ‘Zakk, can you bring over some milk and eggs and feed the dogs?’ I’d say, ‘Yeah Ozz, of course.’ ” And if he wanted a ham sandwich with that? “No problem,” Wylde says, then laughs. “And I’d go light on the mustard!”

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.