Gov’t Mule was an idea before it was a band and a side project before it was a full-time affair.

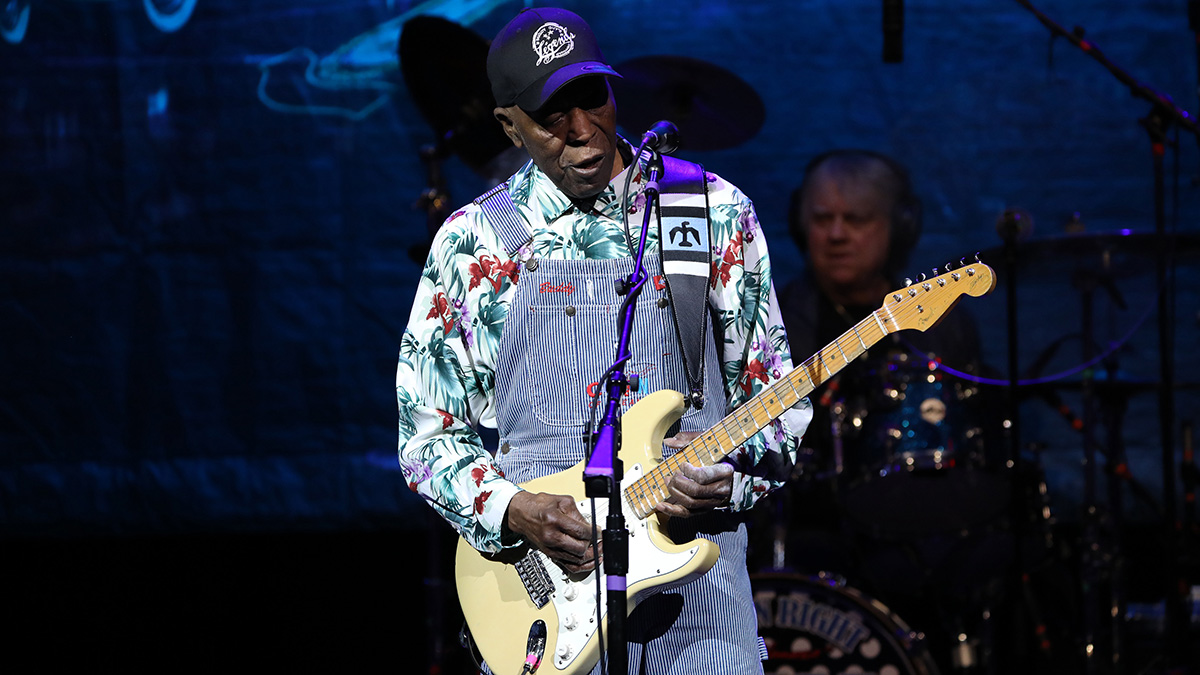

Now, 22 years after its debut, the Mule is an essential, iconic American band, a fact reiterated from the very first note of the group’s new album, Revolution Come… Revolution Go. The album is as diverse and wide-ranging as anything Warren Haynes has recorded in his prolific career, making a strong statement that he is one of his generation’s best and most important guitarists.

“Warren is playing in rarified air,” says Don Was, who produced two tracks on Revolution Come…Revolution Go. “There are very few people in his class.”

After touring for several months with Haynes as part of the Last Waltz 40 celebration of The Band, Was had a good handle on Haynes’ playing ability. Entering the studio together for the first time helped him more fully appreciate Haynes’ talents as a leader, organizer and craftsman—and of Gov’t Mule’s greatness as a band.

“They have the kind of telepathic communication and understanding of one another’s ideas and instincts that mark all great bands,” says Was, who has worked with the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, the Black Crowes, Van Morrison and many other iconic artists. “The musical conversations happening in Gov’t Mule are vivid and highly cooperative and really intense. It’s the kind of thing you can’t just rehearse your way into. It’s chemistry and it comes from great players who really listen—and from years of playing gigs together.”

Haynes and bassist Allen Woody hatched the idea for Gov’t Mule in the early Nineties on late night bus rides in the years after the pair had helped resurrect the Allman Brothers Band and return them to glory. Their vision was an experimental, improvisatory, rock trio in the mold of Cream, Led Zeppelin and Mountain, a heavy but free-range musical form they felt had vanished. They teamed up with drummer Matt Abts and began fulfilling the vision with a 1994 jam at the Palomino Club in Los Angeles.

In October 1995, Gov’t Mule released their self-titled debut and began touring hard around Allman Brothers runs. Their shows were high volume, high intensity musical conversations that could roam from acoustic Delta blues to covers of Black Sabbath, with original tunes that reflected this breadth. In March ’97, as they finished work on their excellent, ambitious second album Dose, Haynes and Woody left the Brothers to focus on the Mule.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

When Woody died in August 2000, Haynes and Abts didn’t know if they could or should continue with the Mule. After recording two albums with guest bassists ranging from Phish’s Mike Gordon and the Grateful Dead’s Phil Lesh to Cream’s Jack Bruce and Deep Purple’s Roger Glover, the Mule toured with a rotating cast of bassists. They decided they would no longer be a trio, adding keyboardist Danny Louis and bassist Andy Hess. Jorgen Carlsson replaced Hess in 2009 and has helped the band return to its aggressive roots even while continuously expanding its scope.

While all that was going on, Haynes also returned to the Allman Brothers band in 2000 and spent years juggling gigs and tours between them, Mule, the Dead, Phil Lesh and Friends and others. Haynes recorded and released a country and folk-tinged solo album Ashes and Dust; his previous solo effort, 2011’s Man in Motion, was an r&b based album.

The Allman Brothers played their final show in October 2014, and with Revolution Come…Revolution Go, Haynes seems to have pushed all his chips onto the Gov’t Mule table. The album, recorded mostly at Willie Nelson’s Arlyn Studios in Austin, includes songs that would have been at home on Ashes and Dust and Man in Motion, as well as a couple that could have been on an Allman Brothers album and several classic Mule rockers.

“You never know where an album is going to head until you get into it,” says Haynes. “I just found myself writing in a lot of different directions and all of them seemed to work together especially when interpreted by the band and our collective personality. You have to work up the songs and see which ones feel like they want to go together because the album concept is still very important to me and I don’t think I’ll ever change my view on that no matter how popular single tracks become. I’ll keep assuming or hoping that most people will agree with that approach.”

“Stone Cold Rage,” the first song on the album, sets a tone, both musically—with a hard edge and some cool alternate sections—and lyrically, where you get very topical. You put your finger on what was happening in the country last fall as clearly as anyone has: “There’s a stone cold rage in the hinterlands.”

It’s something I’ve been noticing for four or five years touring the country. We started recording on Election Day, which became a very important part of this record. Obviously, I was writing the songs before we knew who was going to win, but I was just observing that regardless of who won, the country was going to be more divided than I had ever seen it, and I was feeling that very profoundly and I wanted to address it. A lot of the songs had already taken political connotations and then we were thrown for a loop on the day we were going to record and I’m sure that impacted everything that happened.

But they weren’t written about a [possible] President Trump but about what I saw happening. I think we’re reaching a point where if we don’t start working together it’s going to get worse and worse and worse. It’s up to people to make that happen, regardless of which side you’re on: inform yourself, vote, get involved. That’s what [2013’s] Shout was about, too: the megaphone on the cover was saying, “It’s time to use your voice. Be heard.”

“Stone Cold Rage” opens with a great riff that is really reminiscent of classic early Gov’t Mule, but the album also takes a lot of different directions. More influences pop up than we are used to hearing in the Mule.

I think that’s correct and that’s kind of how we approached this. Obviously, there are some old-school influences that have been around since the beginning of Mule and there are other things that have popped up live but never on an album and we’re just opening it up and bringing them onto a record for the first time.

One of those approaches is having two guitars on a track. The first song where that’s really featured is Drawn That Way. Are they both you?

No. That’s me and Danny, who’s been playing a lot more guitar. We set it up very old-school, with everyone playing together so the parts are nice and raw and me on the left and him on right. I’m playing a Charles Whitfill Tele and he’s playing an SG and the outro solo is just me panned back and forth on my ’59 Les Paul.

I was happy with the way this came out and I think that song has several obvious influences and a few not so obvious ones; I think it has that Beatles-going-heavy vibe you hear on Abbey Road and Let It Be. I really wanted to have some songs on this album with two guitars and no keys.

Why?

Because there are more and more songs that we approach onstage that way and it’s just a different way of exploring what we do, a different way to approach the four-piece thing. There are probably 20 songs in the repertoire now where Danny just plays guitars and this will add to that.

I think it’s cool not to have keyboards on every song and to have the bona fide two-guitar concept played out. And we also used acoustic piano on a few songs, which we’ve very rarely done. Willie has an old standup piano in the studio that was in such disrepair that we had to go through a lot just to get it in recordable shape, but it was totally worth it.

You mentioned that you played the Tele, which I don’t recall you ever doing. Did you use a lot of different guitars on the album?

Yes, I used a lot more than I usually do. I just wanted more sounds, more palettes. In addition to the Whitfill Tele and my ’59 Les Paul, I played my blonde Gibson 335, a 12-string Firebird, my “Dead Bird,” a non-reverse headstock Firebird Gibson built for me when I toured with the Dead, a Strat, a ’58 Gretsch, which a very generous fan gave me, a Firebird, an SG tuned down, and a 12-string Les Paul. I also did more overdubbing than usual, though it was mostly additional rhythm parts. Most of the solos were still cut live.

“Traveling Tune” is another change of pace, with a steel guitar and harmony guitars, which gives it a very Allman Brothers feel—probably more than any other Mule track.

I think so, too, and it was definitely intended that way. It’s not me on steel—what makes the best overall album. We’ve always done that.

I made Man in Motion and Ashes and Dust because I had written so many songs in one direction that it felt like it was time to make a solo record with a distinct approach. But Mule has also had more diversity and balance than people tend to remember—every album has had songs that could have been interpreted on a solo record and we all feel that tempering in a few songs that take it somewhere else have always been a part of what Mule is. Dose had “I Shall Return” and “Raven Black Night” and Life Before Insanity had “In My Life” and “Tastes Like Wine.”

And the title song “Revolution Come… Revolution Go” fits in the history of doing ambitious, multi-part songs.

Yeah. We’ve also had tunes with elaborate arrangements. For instance, “Left Coast Groovies” and “Blind Man in the Dark” are not normal verse/chorus songs. “Revolution Come…Revolution Go” went through a lot of changes. It has a lot of different sections and at one point we were debating whether to make it two different songs or even to include it or not. We went back and forth and in the end we opted for an even longer version with the jazzy section extended and then it felt right and we became very excited about it.

You produced the album, with Gordie Johnson co-producing much of it, and Don Was co-producing two songs. You have done great production work with yourself and others. What does that extra person offer you?

Perspective. It’s really nice to get the thoughts of someone not in the band that you trust enough to mess with your songs. Jorgen and Danny both have really great engineering and producing skills and are doing more of it on their own, as am I, so we have the skills to produce a record. But it’s just nice to have someone to bounce things off, and they’re always going to come up with something we wouldn’t think of; Don and Gordie both have great arrangement ideas. As a band we do a lot of communicating and tossing around ideas and having an impartial voice weigh in can be really valuable.

Don sits in the room with the band while you’re recording rather than in the control room, so he’s feeling the vibe on the floor as the band is playing. The two songs we did together, one was first take, the other was a fourth take and in both cases he said right away, “That sounds like a record to me.” Musicians can feel that as well but they are also thinking about making sure that his performance is right and listening in a different way. Don has a very positive vibe that reminds me of old-school producers like Tom Dowd, who considered part of the job to make everyone feel good and bring out the best in everybody.

Jorgen also shows other sides of his playing. It seems like he has taken a lot of old songs back toward the original, hard-hitting versions. Did you give him any guidance about stepping into a role established by someone else? Woody played some pretty distinct bass lines.

Jorgen does what comes naturally to him and it’s uncanny how similar his instincts are to Woody’s. Prior to joining Mule he wasn’t influenced by Woody but he was influenced by a lot of the same people and their birthdays are a day apart, which must count for something.

Once he discovered Woody he was enamored of his playing. Other than giving him license to be as crazy as he is—most bands don’t accommodate bass playing that’s that aggressive—it just fits with what he wants to do anyhow. It takes a certain type of band to require that aggressive approach to not only the playing but the sound as well and that’s another thing that Jorgen and Woody shared: the love of big nasty bass sound.

We started as a trio, so the bass had to take up a lot of space and kind of be constant counterpoint to the guitar. That’s what makes the whole trio thing work and that carried over to us as a quartet as well. We didn’t back off the aggressive nature of the bass when we added Danny to the picture; we just added keyboards.

You’ve certainly put in your time on the road and “Traveling Tune” is a great song about the life of a band. The line that really struck me was, “Here’s one for the fallen ones that didn’t make it through this life’s challenges and pressures.” Did you write that for Butch [Trucks, Allman Brothers Band drummer who died in January 2017]?

No. It was written before he passed away. But of course I was thinking about him too. I was thinking about a lot of people: Woody, Brian Farmer [longtime guitar tech who died in 2014]. Unfortunately, I had several people in mind.

Once the shock of Butch’s death wore off, a deep sadness for him set in. For fans there was a second sadness: this meant there really would never be an Allman Brothers reunion. Did you feel that at all?

Oh yeah. I didn’t see a reason for the Allman Brothers to reunite any time soon. If it were to ever happen—and I was doubtful it ever would—there would have to be a reason like Dickey [Betts] coming back or making a new record, or the 50th anniversary in 2019. That’s something Butch and I talked about at length and when I got the news of his passing I realized that’s completely gone.

After he died, you eulogized Butch by calling him “a dying breed of musicians who served with honor like soldiers,” which really struck me.

I always felt that way about him and the longer I played with him the more strongly I felt it. I can remember times when he was in physical pain and would just get up there and give 110 percent, which is what he felt the music deserved. He never took even a song off. He was part of a dying breed of people who took the music that seriously and sunk themselves that deeply into it. Even what musicians went through in his day to achieve what they achieved is hard to fully grasp.

The Allman Brothers became very successful but they were out there doing thousands of miles in a van and then in a Winnebago doing 300 gigs a year. That’s being a soldier. I don’t know how many bands these days would do that and are capable or driven enough to do that and it all paid off: they improved by leaps and bounds each year, from 1969 to 1970 to 1971. That’s due to individually and collectively being in the trenches and being completely immersed in the music and also doing hundreds of gigs that get you to that point. Butch maintained that drive all the way to the end; I don’t think he ever backed off or away from anything. No one worked harder than him.

Well, you’ve often been called the hardest working man in rock for all the gigs you’ve juggled and the length of your shows.

Yeah, but I’m not a drummer! I play enough drums to realize that I’m wiped out in 15 minutes. People like Butch and Matt get up there and play for three hours and that’s just some unique sort of energy and stamina that the rest of us don’t have.

You played a tribute to Little Feat’s Waiting for Columbus in New Orleans. Was Lowell George a big slide influence?

Yes. I discovered the Allman Brothers’ music before I discovered Little Feat’s music but once I became a Little Feat and Lowell George fan I definitely was very influenced by his approach to slide guitar. There are only a handful of people I studied a lot: Lowell, Duane, Johnny Winter, David Lindley, Ry Cooder and Bonnie Raitt. They all seeped into my vocabulary.

I was a big fan of Duane and the Allman Brothers early on and started playing slide guitar when I was about 14. When I started working with Dickey I had been focusing on slide for a few years and playing with him gave me a reason to really hone in on it and to play a lot of slide guitar onstage.

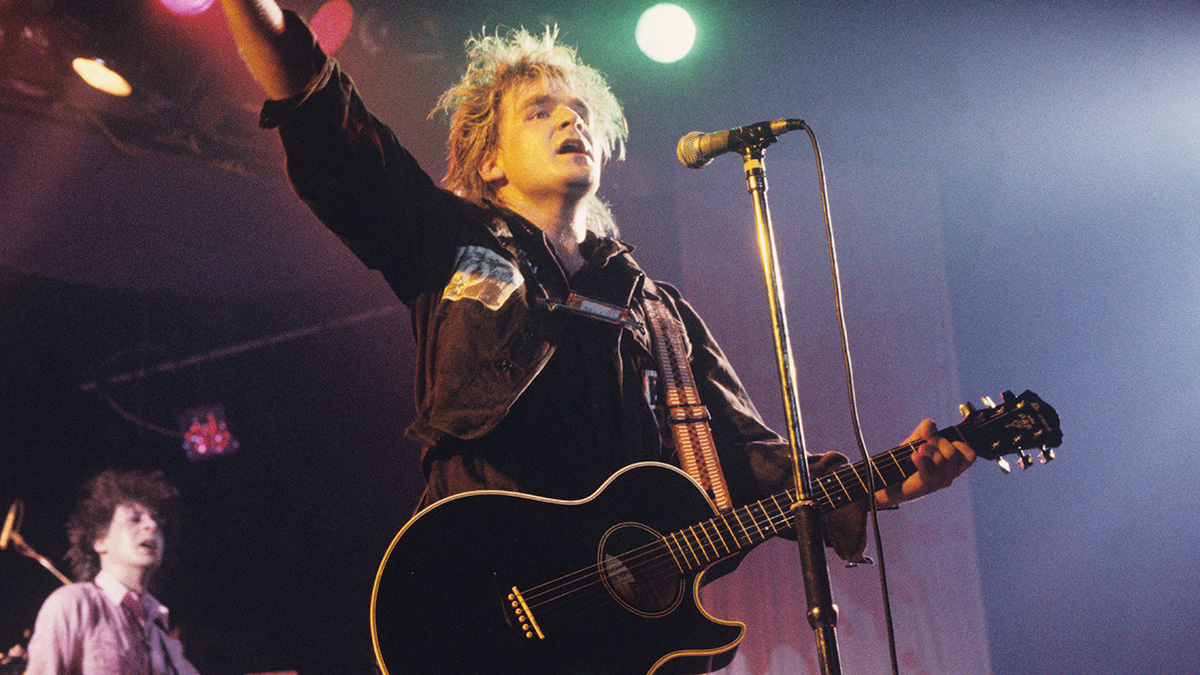

The Last Waltz 40 tour began as a one-off concert in New Orleans with the same people. Will you take this one on the road as well?

No, I don’t think so. I see it as one-off. I think it’s going to be full-tilt, 100 percent Mule for at least a year. This is the most important thing and I don’t see any reason to take on anything else.

Your management is working with Marcus King and you produced his last record. Congratulations on the success. Will you keep working together?

Thanks. I’m really confident that he’s going to have an extremely bright future. He’s a great singer, a great guitar player, a great songwriter and people are responding positively on every level. I’m proud to be part of this record and we’re talking about the next one and I’d be happy to do anything that they want me to do. I love them and really believe in him.

It’s impressive that you were so productive the week after the election because everything was sort of upside down. Half the country went into a depression while the other celebrated—and no one felt much like proceeding with normal life.

I normally stay on top of the news day to day and I didn’t do any of that for about two weeks. I buried my head in the music and didn’t pay attention to anything that was going on. It was a bizarre way to start a project, but it was the best thing for me to be doing for my own mental health!

Do you feel any apprehension about sharing your political beliefs and feelings in such a polarized world? Any concern that it could cost you fans?

My political opinion is public record. It’s been there on every record I’ve written and recorded since [1993’s] Tales of Ordinary Madness, so if you’re really paying attention you get a grasp of where I stand. Of course, some people are just listening for an overall music perspective and not paying much attention to the words, but the Allman Brothers and the Dead raised $1 million for Obama. We were big supporters so it’s not a secret. I would like to think kindness wins over fear and hatred but it’s a sine wave that goes up and down.

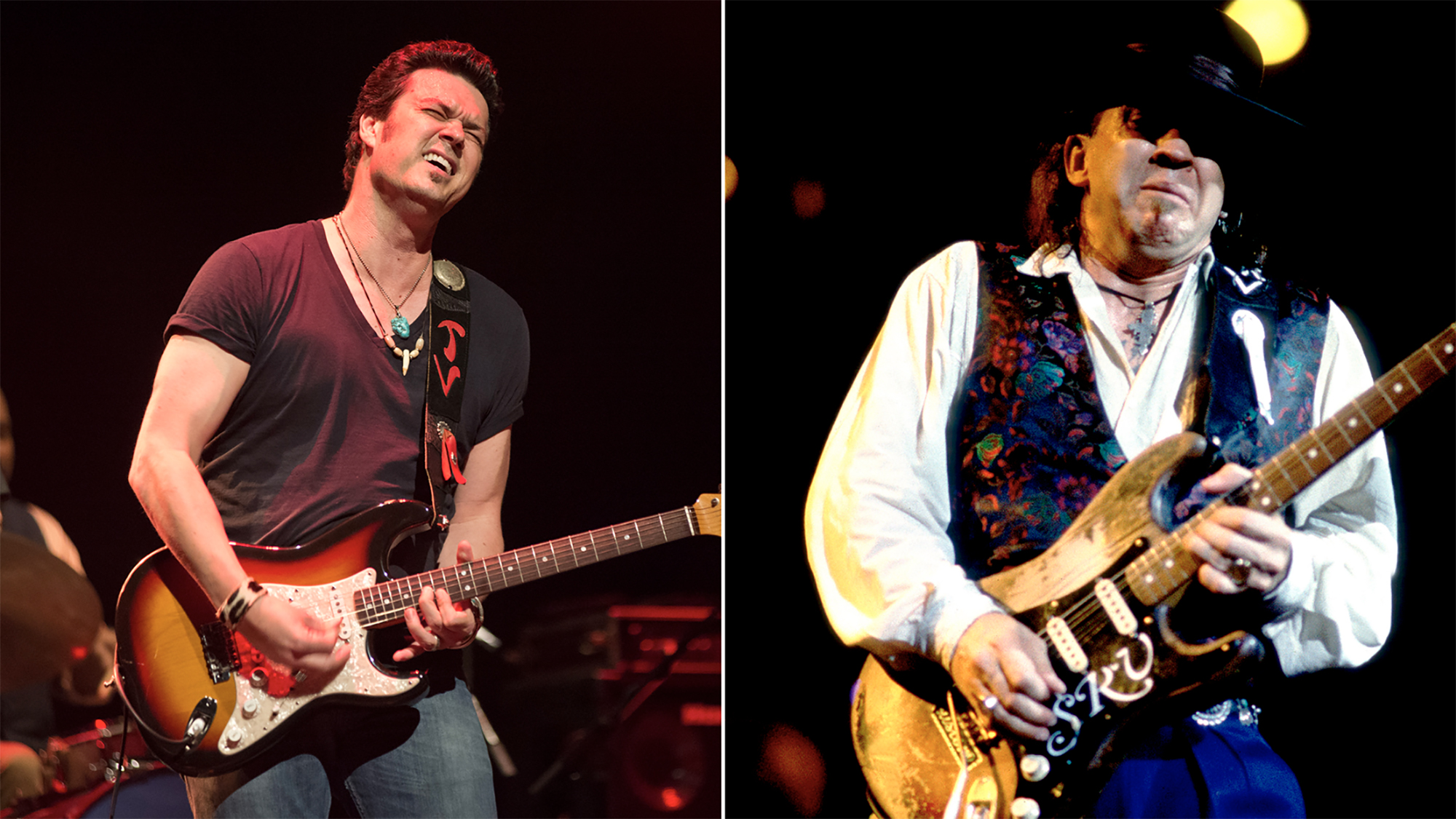

Alan Paul is the author of three books, Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan, One Way Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as Managing Editor from 1991-96. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort.