Venom's Cronos Reflects on the Band's Career and New Album, 'From the Very Depths'

There’s a toothy bite in the air, and the blustery wind makes it uncomfortable to be outside for more than a few minutes.

Once again, the temperature in Newcastle Upon Tyne, England, has dropped below freezing.

In other words, it’s another cold day in Hell for black metal pioneers Venom—the perfect weather for frontman Cronos to sit by a crackling fire at his home and talk about the turbulent history of his band and the creation of its eleventh album From the Very Depths.

“It feels good to be out there again,” says Cronos, who last worked with Venom on 2011’s Fallen Angels. “People ask why it took four years. Well, I don’t believe creativity can be forced and I will not have a record company getting a stick out and saying, ‘hurry up, hurry up.’ I’m too late in my career to be releasing stuff under pressure.”

Cronos has learned from experience that rushing albums is a bad idea, and, having established himself as one of the pioneers of both thrash and black metal, he has earned the right to his devil-may-care songwriting approach.

He wasn’t always so relaxed. When Venom surfaced in 1979 from Newcastle, England—about 250 miles north of London—they were the most aggressive, abrasive and confrontational metal band in England. Black Sabbath had sung about the devil; Venom’s entire first album, 1981’s Welcome to Hell, was a love letter to Satan. It was also one of the first releases to integrate the speed of punk with the steely tones of bands from the New Wave of British Heavy Metal.

“I used to listen to Sabbath, and Ozzy would be going off about all the fuckin’ witches or elves. And then all of a sudden he would cry, ‘Oh, God, help me!’ And I would think, Oh no! You’re supposed to be the evil bastard. Why are you asking God for help?” says Cronos in a strong working-class accent that’s not quite as hard to understand as Lemmy’s.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“So I decided I would be the evil bastard. But the music had to be evil, too. So, while all these other groups would get to their lead breaks and play these pretty little leads, I wanted to have divebomb solos and guitars crashing against amplifiers and all this madness.”

Extreme music fans took a shine to Venom, which, from the get-go, sounded like Motörhead with lyrics by Church of Satan founder Anton LaVey. But unlike many of their disciples, Venom, like Black Sabbath, were never goat-sacrificing devil worshippers. They found an image that matched their discordant music and pushed it to the hilt. “Since day one, we said, ‘We are horror movies to music,’ Cronos says. “If Black Sabbath were Frankenstein, Venom are the Evil Dead.”

Somehow, Venom still appeal to those who seek music outside of the norm. And that’s after numerous lineup shifts (Cronos is the only original member), several substandard albums, and a contagion of faster, more dissonant death and black metal bands.

For those in the know, there’s a wicked charm to Venom. Even Dave Grohl loves Cronos and handpicked him to guest on his 2004 side project Probot. And Venom’s legions continue to grow amongst fans that weren’t born until after the release of Slayer’s God Hates Us All. This summer, Venom will play numerous festivals across Europe that cater to fans of all ages. More recently, they were one of the highlights of January’s 70,000 Tons of Metal cruise, even though the airline they flew in on lost their gear and they had to borrow equipment from Arch Enemy for two shows, one of which was on the outdoor pool deck.

“The shows were great and the place went fucking mental,” says guitarist Rage, who joined Venom in 2007 and has played on three albums. “There were hot tubs in the middle of the crowd and all these people with pentagram and inverted cross tattoos were moshing in there. You’ve never played a proper gig until you’ve seen a circle pit inside a hot tub.”

The perennial interest in Venom stems in part from their theatrical and explosive live shows, but also because of the mystique they’ve built up since the release of 2011’s well-received Fallen Angels.

From the Very Depths, the third to feature the lineup of Cronos, Rage and drummer Dante, is truer to the band’s original sound than anything since 2000’s Resurrection, the band’s last album to feature original guitarist Mantas. Granted, the production is cleaner, the playing is tighter and the separation between instruments is more distinct than the band’s early output, but anyone who enjoys trebly, buzzing guitars, noisy solos, booming bass lines, double-bass drumbeats and growling Satanic vocals should cherish From the Very Depths like an old Crowley text.

“The record is so good because the guys I’m playing with now are so excited that, not only do they love playing this kind of music, they don’t want to stop,” says Cronos. “If I say to them in the studio, ‘Play it again,’ they’re already playing before I fucking finish my sentence. That never happened before. [Original drummer] Abaddon and Mantas were always looking for excuses not to have to play something again.”

In addition to bringing a new hunger into the group, Rage and Dante, having grown up listening to the band, are reverential of Venom’s storied history. “I’ll never forget when I first heard them,” Rage says. “Me and a group of my friends all had mullets and we used to go to each other’s houses and listen to albums. One day one of the lads brought in the 12-inch of Venom’s ’Nightmare’ single [from 1985]. We were blown away not just because the music was so insane but because we were from Newcastle as well and we all were making our first steps into learning how to play guitars and form bands. I never would have imagined that I would be playing with Venom 30 years later.”

Today, Cronos is one of the most notorious bassists in extreme metal, but in 1979 few could have imagined he had any future in music. He wasn’t even a bassist. When Venom formed out of the ashes of three other bands, Cronos played rhythm guitar. Then, a week before one of Venom’s early shows at the Meth in Wallsend, original bassist Alan Winston got cold feet and abruptly quit. Since Cronos was working as an assistant tape engineer at Impulse Studio in Newcastle, he was able to borrow a bass from a musician at the office.

“I figured we were never going to be able to get a bass player in five days and teach him the songs,” Cronos says. “So, I played the root note of the chords on the bass for the gig. The only equipment I had to plug into was my Marshall amp and all my pedals. And something magic happened. It sounded fucking amazing. So I said, ‘Fuck it, I’m the bass player now!’ ”

Venom’s early gigs were sloppy and chaotic. During a March 1980 show at Newcastle Westgate Road Church Hall, the band set off so many smoke pellets that the musicians were left literally gasping for breath. It wasn’t the last time Venom’s pyro endangered the band or crowd, but watching the band practically burn down venues was a part of their early appeal. With a solid, theatrical live show assembled, the next step was to make a decent demo. Since Cronos worked in a studio, he hoped he could make a quality recording of the band without much fuss. But Venom lacked the money to pay for a session and Cronos’ boss wasn’t interested in supporting a crazed Satanic metal band. At the time, the studio’s bread and butter came from U.K. folk music. Cronos basically had to sell his soul to get Venom in the Impulse recording room.

When Iron Maiden hit the charts with “Run to the Hills,” Cronos’ boss realized that he might be able to make some extra cash recording local metal bands. So he asked Cronos to comb the hills for fresh talent, and the bassist recruited Raven, White Spirit, Tygers of Pan Tang and Fist to record sessions for the company’s dusty imprint Neat Records, which had previously only released failed recordings by a band called Motorway and a child singer.

Since there was a sudden surplus of bands at the studio, the engineer needed more help. Cronos struck a deal with him. “I was working nine to five and sometimes these sessions went through the night, so by 5 P.M. the engineer was fucked because he had nobody to help him,” Cronos recalls. “I said to him, ‘Look, I’ll work as long as you want in these sessions if you will give me a day of your time for free to record my band,’ because I couldn’t afford studio time. He agreed and then I went to the guy who owned the place and said, ‘The engineer has agreed to work a day for my band for free. Can I have a day in the studio? I’ll do whatever you want.” I ended up washing cars, sweeping the stairs and cleaning the toilets just to get that day in the studio. But we got to go into the studio and put down the stuff we had.”

Cronos hoped to record a decent demo and then shop it around. Since he had experience in the studio, he felt comfortable. Mantas and Abaddon, however, were as nervous as unprepared students at final exams. “They were shitting their knickers,” Cronos says. “There were quite a few times I actually tricked the guys because every time we pressed the record button they would make mistakes, but when we did run-throughs they seemed to play okay. I told the engineer, ‘Look, when I give you a signal, press the record button,’ and then I would turn to the guys and say, “We’re not recording this. It’s just a run through.’ Little did they know the tape was on and were recording the whole time.”

By the end of the session, Venom had a usable demo. Granted, it wasn’t the highest quality recording since they were rushed, the instruments weren’t exactly in tune and there were moments when the rhythms were slightly off-time, but Cronos figured it was good enough to get Venom a deal. It was, but not in the way he had hoped.

“The guys at Neat thought we were going nowhere and didn’t have a chance, so when I asked them if we could go back in and record the songs proper they said, ‘Look, we’ll just release these demos as they are as an album. That’s it,’ ” Cronos recalls. “I said, “Hell no! We need to record it the right way so there are no mistakes.’ And the label said quite bluntly, ‘We’ll release it like this or we don’t release anything.’ So what do you do? You’ve just been offered an album release. Only an idiot would turn that down.”

When Welcome to Hell came out in 1981 it was a double-edged sword. As Cronos expected, Venom were accused of being poor musicians with ramshackle songs and the “no-talent” tag dangled from Cronos’ neck like a backstage laminate. “Nobody thought we could play just because they based everything on that crap recording,” Cronos laments.

In 1983, Megaforce Records founder and concert promoter Jonny Z flew Venom to New York to play two shows in Staten Island with Metallica. Cronos wanted to make sure the concerts went off with a bang, so he contacted Jonny three months before the concert and asked him to secure a box of explosives. Jonny refused, so Venom stuffed dangerous pyro inside their cabinets and shipped them by boat to New York, where they arrived three months later, just in time for the gig.

“When this big truck got to Jonny Z’s house, we took all the equipment out, got some screwdrivers and took these cabinets apart,” Cronos says. “We started pulling out all this titanium and fuses and blasting power. Jonnny was losing his mind.”

While they were hanging out with Metallica, James Hetfield turned Venom on to Exodus, Slayer and Testament, and for the first time since he discovered Discharge, GBH and Motörhead, Cronos was genuinely excited about another thriving musical movement. “I became really good friends with Kerry King and Slayer. When we took them on the road they were driving in a minivan and Kerry was traveling with his pet snakes. He had all these snakes under the front seat and we were going back and forth from the States up to Canada. Every time he had to get these snakes across the border without them being detected.”

Touring with American thrash bands was fun and inspiring for Venom, but between the drunken parties and debauchery the band was falling apart. “The rot really started to set in several years into our recording career,” Cronos says. “There was just a lack of devotion that built up. I was in the studio with Abaddon lots of times, and he would screw up a take. I’d say, ‘Okay, let’s do it again.’ And he would go, ‘C’mon, I’ll just put an echo on it and it’ll be okay.’ I could never understand why he didn’t want to do it again. Why wouldn’t you want to play your instrument? Things went downhill from there. A lot of resentment built up and we all went different ways musically.”

Mantas left Venom in 1985 after the band released Possessed and Cronos and Abaddon forged ahead with two hired gun guitarists, Mike Hickey (Mykus) and Jimmy Clare, and recorded The Calm Before the Storm. The album included keyboards, previously absent guitar hooks and semi-melodic vocals, and was largely viewed as a commercial cash-in; immediately, it flopped. Cronos left the band out of frustration and Mantas and Abaddon worked together with vocalist and bassist Tony Dolan (who still plays with Mantas in M-Pire of Evil) on three largely forgettable Venom albums. Cronos recorded two solo records, then returned to Venom for the shaky 1997 record Cast in Stone, which was hardly the reunion fans had hoped for.

“The thing is, those guys changed,” Cronos says. “Abaddon wanted to sound like Marilyn Manson. There are two songs on Cast in Stone, ‘Domus Mundi’ and ‘Swarm,’ where Abaddon used some weird techno fucking drumbeats. It’s not even a real drum kit. I let him do it because we were all equal members in Venom. Those are probably the two most hated songs in the history of the band.”

Cronos’ relationship with Mantas deteriorated more quickly once Abaddon quit. Cast in Stone’s follow-up, 2000’s Resurrection, had its moments, including the title track, “Loaded” and “Pandemonium,” but overall Mantas sounded like he’d rather have been playing for Prong or Pantera. “He went off on some kind of grungy, industrial type riff thing which I couldn’t understand,” Cronos says. “I was like, ‘Dude, why the fuck are you changing the style you helped make famous?’ ”

Mantas quit in 2002 due to irreconcilable differences, and Cronos scrambled to reconstruct Venom—again. He kept his younger brother Annton, who had played drums on Resurrection, and called back Mykus. The songs on 2008’s Metal Black felt forced and Mykus, who lived in the States, was unable to travel to England for tour rehearsals. It was a blessing in disguise. Cronos hired local LaVey lookalike Rage to practice with the band and tour for the record.

“It was great because there was no pressure,” Rage says. “I was just helping the guys out. The pressure came during the first few gigs because you don’t want to be the one who brings Venom down.”

Cronos had such a good time touring with Rage that he asked him to join the band and contribute to the roaring, blasphemous Hell. Having worked together on two albums, the current Venom lineup seems as stable as it is ambitious. So when the band members got together in Cronos’ home studio in March 2014 they felt comfortable, even if they weren’t fully prepared. On past albums, Cronos or his band mates came in with full songs and showed them to the other guys. This time, they jammed extensively and turned the best parts they came up with into songs.

“We’ve been going five years with this lineup and it just keeps getting stronger,” says Cronos. “I finally feel like I’ve gotten beyond all these years of hiring and firing people who fuckin’ joined the band for all the wrong reasons. These guys think like me and are in this industry for the right reasons—to create great music and put on fantastic shows.”

photo by Ester Segarra

Jon is an author, journalist, and podcaster who recently wrote and hosted the first 12-episode season of the acclaimed Backstaged: The Devil in Metal, an exclusive from Diversion Podcasts/iHeart. He is also the primary author of the popular Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal and the sole author of Raising Hell: Backstage Tales From the Lives of Metal Legends. In addition, he co-wrote I'm the Man: The Story of That Guy From Anthrax (with Scott Ian), Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen (with Al Jourgensen), and My Riot: Agnostic Front, Grit, Guts & Glory (with Roger Miret). Wiederhorn has worked on staff as an associate editor for Rolling Stone, Executive Editor of Guitar Magazine, and senior writer for MTV News. His work has also appeared in Spin, Entertainment Weekly, Yahoo.com, Revolver, Inked, Loudwire.com and other publications and websites.

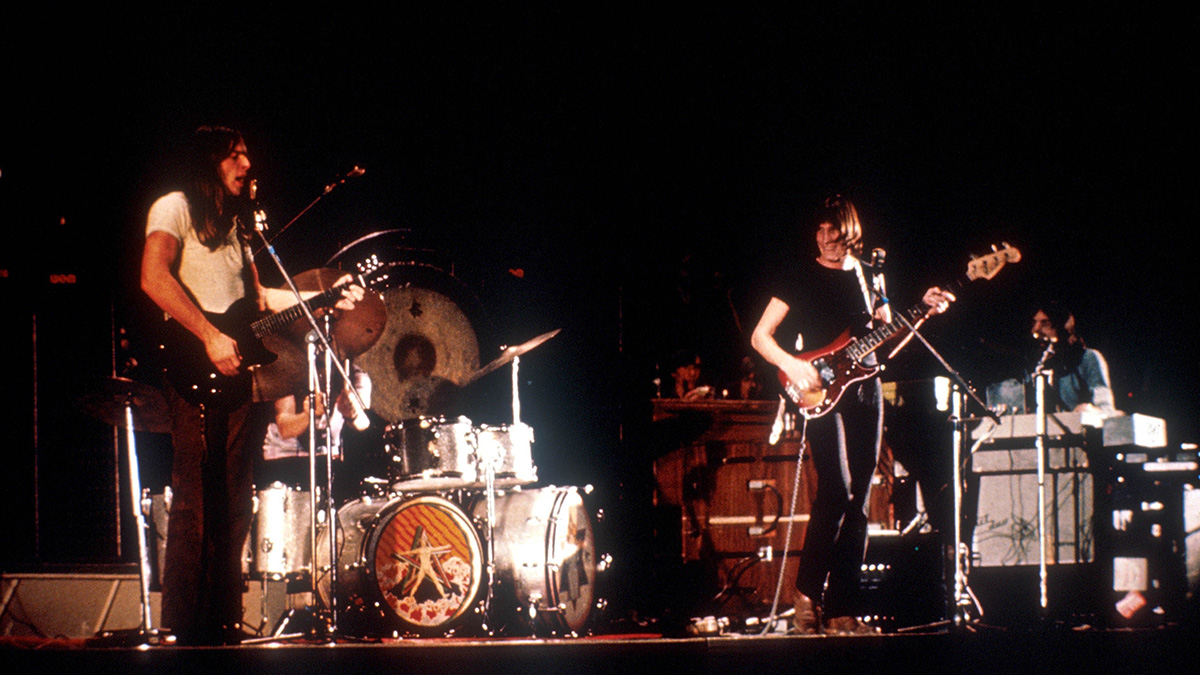

“We hadn’t really rehearsed. As we were walking to the stage, he said, ‘Hang on, boys!’ And he went in the corner and vomited”: Assembled on 24 hours' notice, this John Lennon-led, motley crew supergroup marked the beginning of the end of the Beatles

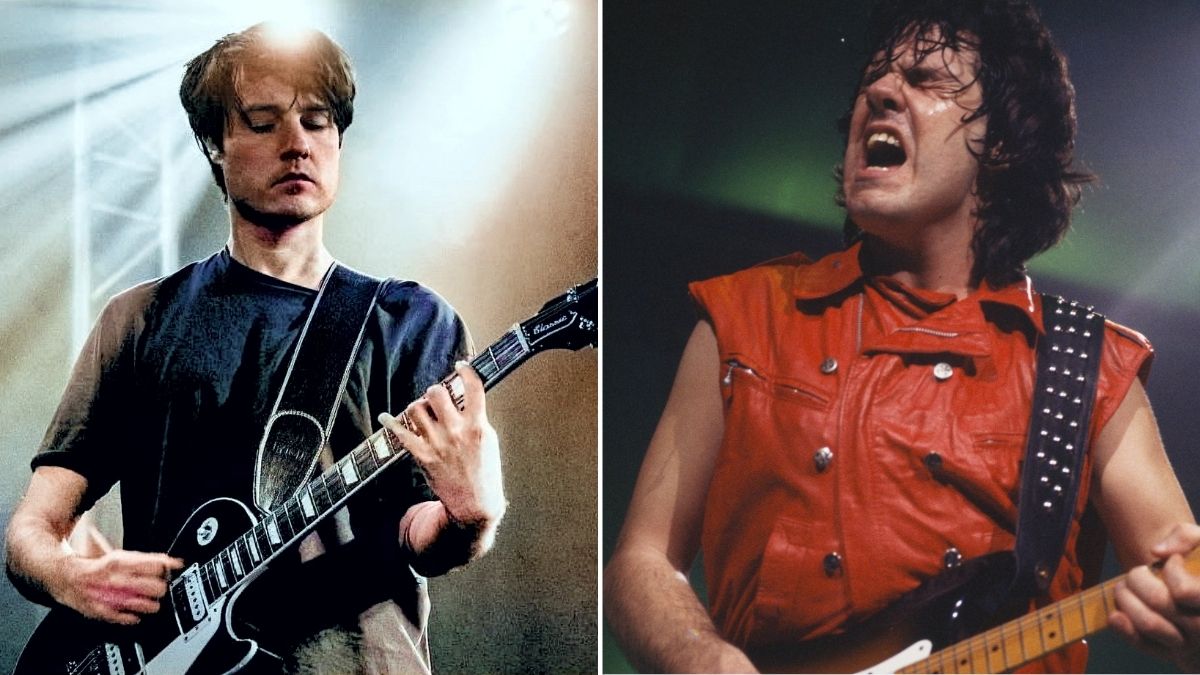

“I pushed myself to down-pick faster and make the riffs more aggressive. Maybe it’s the old man in me struggling to feel young and fighting back against aging”: How Killswitch Engage went to thrash metal bootcamp to deliver their face-ripping return