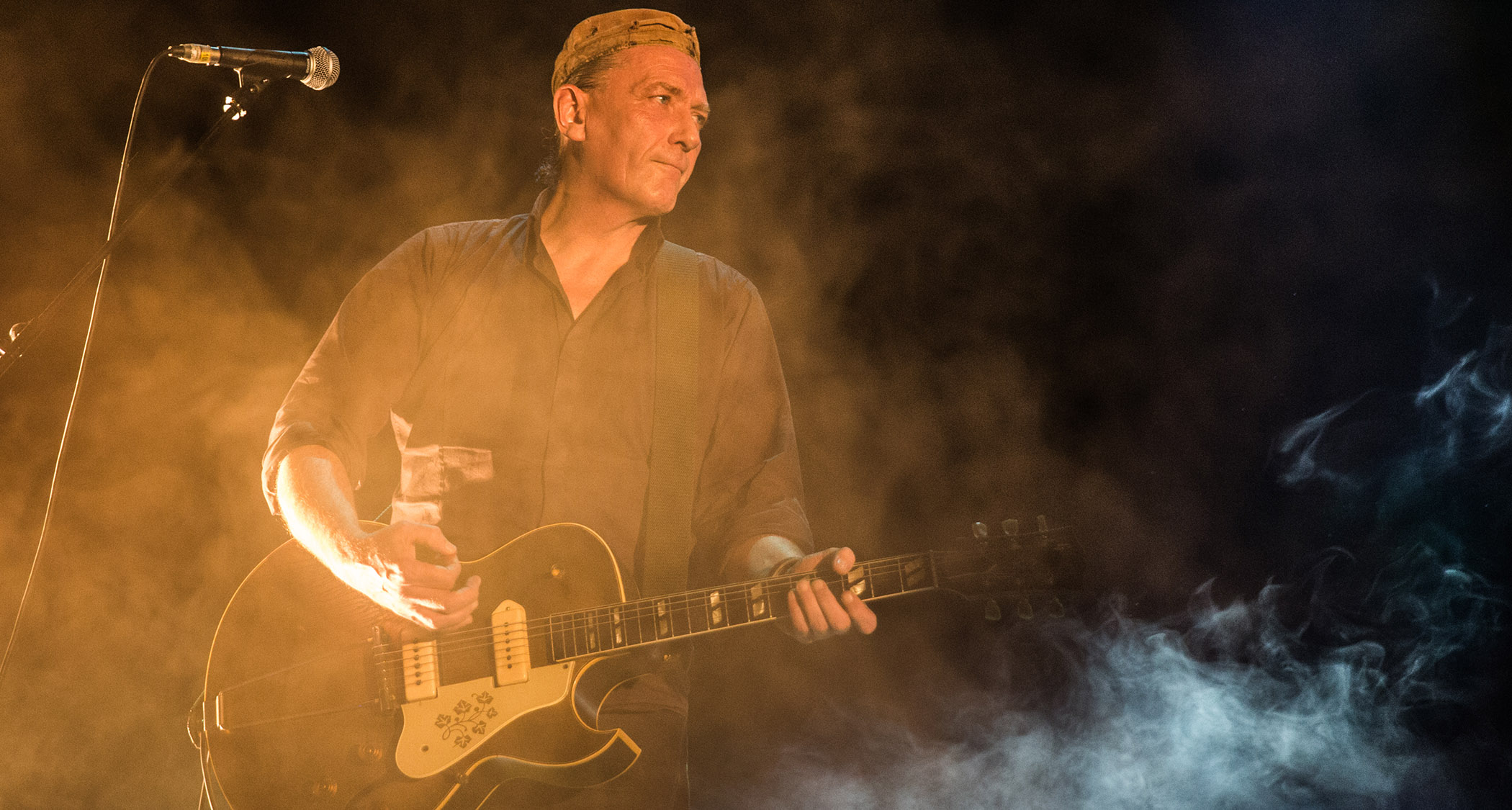

Tyler Bryant: "If I don’t have a guitar on me, I don’t want to be in public... ever!"

Shakedown guitarists Bryant and Graham Whitford break down the riff-rocking but heartfelt Truth and Lies

You’d forgive a little weathered cynicism in Tyler Bryant’s voice. After all, the guitarist/vocalist is at home after a few tour dates with his hard-rocking band, Tyler Bryant & The Shakedown, but the break is brief and he’ll soon be back out on the road. The band is just weeks away from the release of their third album, Truth And Lies, and once that drops, touring in earnest will begin.

All this for a 28-year-old who has played hundreds of road dates over the past few years, with some of them in support of legendary hard-rock acts like AC/DC and Guns N’ Roses (and still others playing house band for the sorely missed Chris Cornell).

Before forming the Shakedown, Bryant had already put together an impressive resume, gigging with veteran bluesman Roosevelt Twitty and touring with Jeff Beck.

It would just seem reasonable to find a grizzled road dog on the other end of the line for our interview. Instead, I found an exuberant guitar nerd, still eager to get down into the essential details of his rig.

“If I don’t have a guitar on me, I don’t want to be in public... ever!” he jokes about his guitar-hermit tendencies.

Bryant’s excitement for guitars can be heard all over Truth and Lies, which is chockablock with the kind of raunchy riffs that used to dominate commercial radio in the '70s and '80s. Throughout the record, Bryant solos with abandon over a swaggering rhythm anchored by co-guitarist Graham Whitford.

From the Sabbath-y doom of the verses on album opener Shock and Awe to the '90s grunge ballad sounds on closer Couldn’t See the Fire, Bryant and Whitford coax a wide array of clean, distorted, slide and acoustic tones from their rigs.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

To that end, the pair shook things up in the studio a bit this time around. While Bryant relied primarily on his trusty stable of Fender Strats on Truth and Lies, he came to the recording sessions with just one amp.

I realized the Les Paul is so punchy; it just seemed to my ear to complement the Strat. It just fills out the other side of the tonal spectrum

Graham Whitford

Onstage, he relies on cranked Orange amplifiers, but the notoriously loud amps can be impractical in a recording studio. For the album, he brought in an Austin-built Square amp made out of old tube radio parts. It ended up forming a huge part of his tone - at a much more reasonable volume.

“It’s like a four-watt Champ, essentially,” Bryant says. “It’s just an old radio, and I used that on most of the record along with Fender Champs and Princetons, essentially. The Princeton would stay a little bit cleaner than the Champ and the Square, but I think in the studio it helps sometimes to use low-Wattage amps that sound like they’re on the verge of exploding. I really love the way that sounds.”

For his part, Whitford relied on his own army of Gibsons. While the Strat-Les Paul tandem is a time-tested tradition, it’s one the band stumbled on accidentally.

“I grew up being a Strat guy - that’s what I learned to play on; it’s Stevie Ray Vaughan and Jimi Hendrix,” Whitford says.

“When I picked up a Les Paul, it always felt cool but foreign. It never felt like home. I got a Les Paul when I was 17, and one day, I thought to myself, I should dust off this Les Paul and bring it to rehearsal. I did and literally from that moment I realized the Les Paul is so punchy; it just seemed to my ear to complement the Strat. It just fills out the other side of the tonal spectrum.”

With both guitarists playing through low-wattage combo amps, the gear played an important role not just in the tones, but in the approach the band took. The songs were recorded live on the floor in Brooklyn’s Studio G, a task made easier without having cranked Oranges and Marshalls blaring.

The live feel is evident in the loose (or “janky,” as Bryant puts it) timing of the rhythms, making for an album of old-fashioned, not-entirely-error-free rock and roll.

We’d all sit around and listen to it and realize, ‘Hey, what if we tried this one more like Alice in Chains and less like Bonnie Raitt?”

Graham Whitford

“That’s what gives us the danger that rock and roll is supposed to have because it’s so easy to just overthink music these days, especially when you’re looking at it and not just listening to it,” Bryant says. “You can look at it in Pro Tools and line it up with your eyes, but then you’re sucking the humanity out of it.”

That go-by-your-gut way of doing things inspired some pretty unexpected directions once the band was in the studio.

“There were certain songs I kinda had on the bottom of my list as far as songs I thought should make the cut, but when we would get in the studio and Joel [Hamilton], our producer, would say, ‘All right, let’s try this one.’

“We’d all sit around and listen to it and realize, ‘Hey, what if we tried this one more like Alice in Chains and less like Bonnie Raitt?” Whitford says.

The guitar interplay on the record shows just how in sympatico the pair have become over the course of three albums.

“When it comes to filling out the rhythm, kind of providing the backbone of songs, that is Graham’s specialty,” Bryant says. “He has this way of completely staying in the pocket and playing just sloppy enough that it has the right attitude. He has just the right amount of ‘F you’ in his playing.”

Of course, when it comes to writing complimentary guitar parts, the band doesn’t have to look far for inspiration. Whitford admits to looking to his dad Brad’s band for examples of what to do.

“A lot of times I’ll honestly think about Aerosmith and how interesting both Joe [Perry] and my dad’s parts are, separate from each other,” he says. “They compliment each other so well, which is something I feel I’m always striving for. How can I make this more interesting? That’s the most fun, figuring out that stuff.”

I get so anxious and have panic attacks. That’s something I just deal with, and music has always been medicine for me

Tyler Bryant

While the sonics of Truth and Lies brings to mind the free and easy attitudes of the hedonistic rock bands of yesteryear, the lyrical content is decidedly more modern. A sense of anxiety and unease hangs over tunes such as Shape I’m In, Panic Button and Judgment Day.

“Don’t judge me by the shape I’m in,” Bryant mournfully howls on Shape I’m In, and there might not be a more succinct way of summarizing the United States in 2019. These days, every day feels like a panic attack ready to happen and Bryant said he’s hardly been immune.

“I get so anxious and have panic attacks. That’s something I just deal with, and music has always been medicine for me,” he says.

“The artists I’m drawn to are the artists I feel are speaking their truth and aren’t trying to come off cooler than they are. A song like Panic Button is virtually just me trying to empower myself and use music to do so. Same thing for Shape I’m In. I think it was important for me to write these songs lyrically because I need the medicine, man. This is what I’ve got.”

If music is proving to be good medicine, then so is what passes for stability in the rock and roll life. After years of tumultuous relationships with their labels, Tyler Bryant & the Shakedown now seem to have found a somewhat permanent home. The new album is their second on Snakeskin Records, and Bryant says what didn’t kill the band only made it stronger.

All told, Truth and Lies is a hard-rocking album that, in the grand tradition of rock and roll, combines hooks with danceable grooves and just the right amount of guitar pyrotechnics.

It’s a formula that on paper seems destined for record sales and likely to put the kibosh on the latest round of 'Are guitar solos dead?' think pieces that circulate every decade. The movement seems to have some loose geographic associations too, with Nashville, traditionally known as being a country capitol, producing a few stellar acts alongside the Shakedown.

Real rock and roll, and roots music has always been there, but I think we’re moving back toward the mainstream with it

Tyler Bryant

“I think there’s a lot of people here, even that aren’t musicians that appreciate rock,” Whitford says.

“The Struts came to Nashville a few months ago and Tyler and I got up and jammed with them, but they did three ‘sold-out’ nights at the Basement East, which is a 600-people cap room. To see that was cool; people in Nashville know what’s up.

“Halestorm’s out of here and they’re good friends of ours. There’s this cool community of bands and people that kind of hang out together. It sort of, to me, has a family-oriented vibe to it.”

The only problem is that rock music has been here before. A decade ago, it was the Strokes and the White Stripes putting rock music temporarily back on the map. Now, pop, hip-hop and EDM seem even more firmly entrenched as the music of the current generation.

But Bryant is confident that his band and contemporaries, like the Temperance Movement, Greta Van Fleet and Rival Sons, can keep the spirit of their rock ancestors (and, in Whitford’s case, his literal ancestors) alive.

“Real rock and roll, and roots music has always been there, but I think we’re moving back toward the mainstream with it,” Bryant explains.

“We’re not changing anything we’re doing. We’ve been doing this since we started the band and we’ve been doing it regardless of what anybody tells us to do. The truth is, we just love real rock and roll.”

Adam is a freelance writer whose work has appeared, aside from Guitar World, in Rolling Stone, Playboy, Esquire and VICE. He spent many years in bands you've never heard of before deciding to leave behind the financial uncertainty of rock'n roll for the lucrative life of journalism. He still finds time to recreate his dreams of stardom in his pop-punk tribute band, Finding Emo.

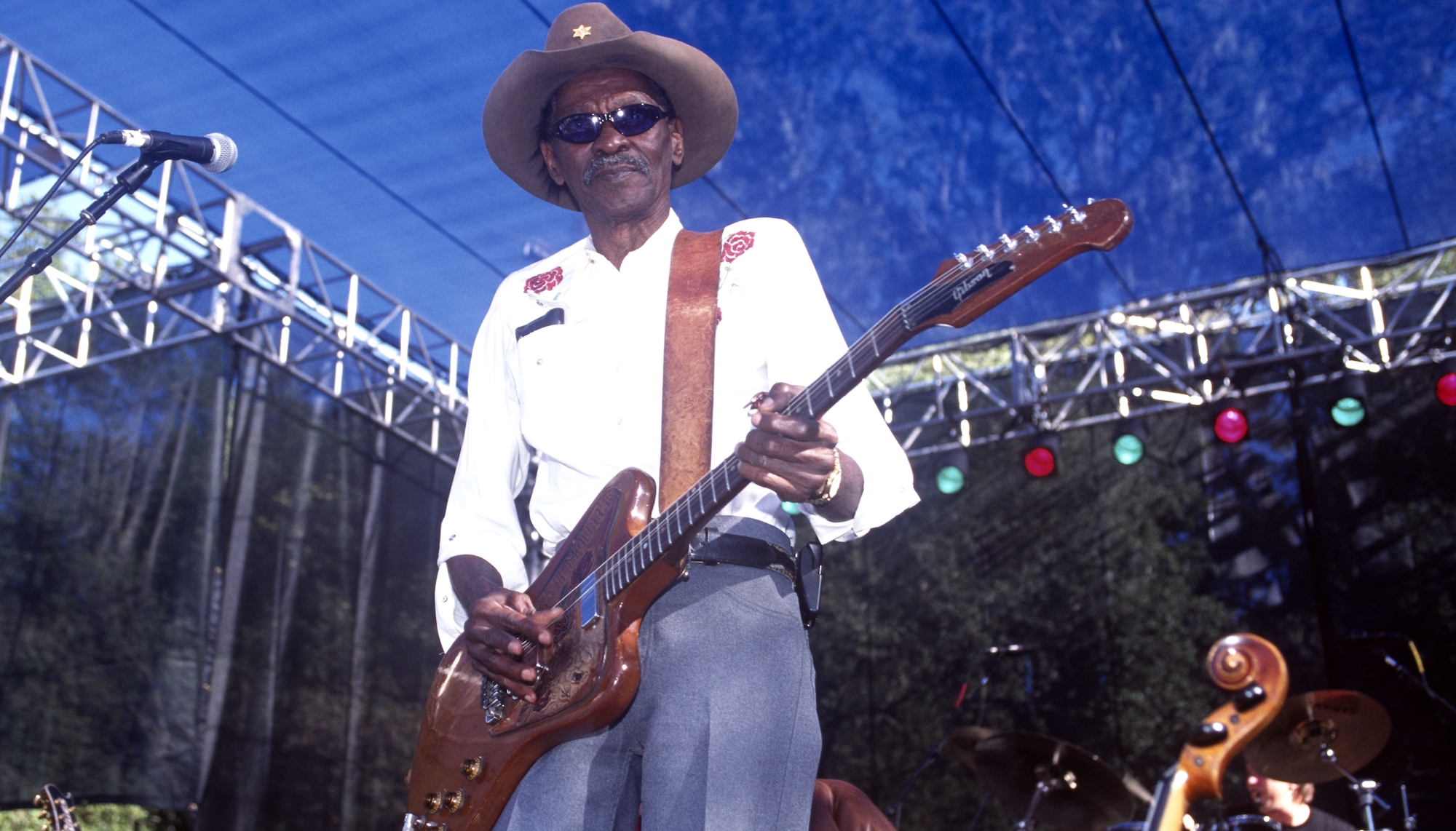

“Chuck Berry's not a very good guitar player. He's a clown. He runs all over the guitar, just like any one of these old rock players would do, and makes no sense”: Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown pulled no punches when speaking about his fellow guitar heroes

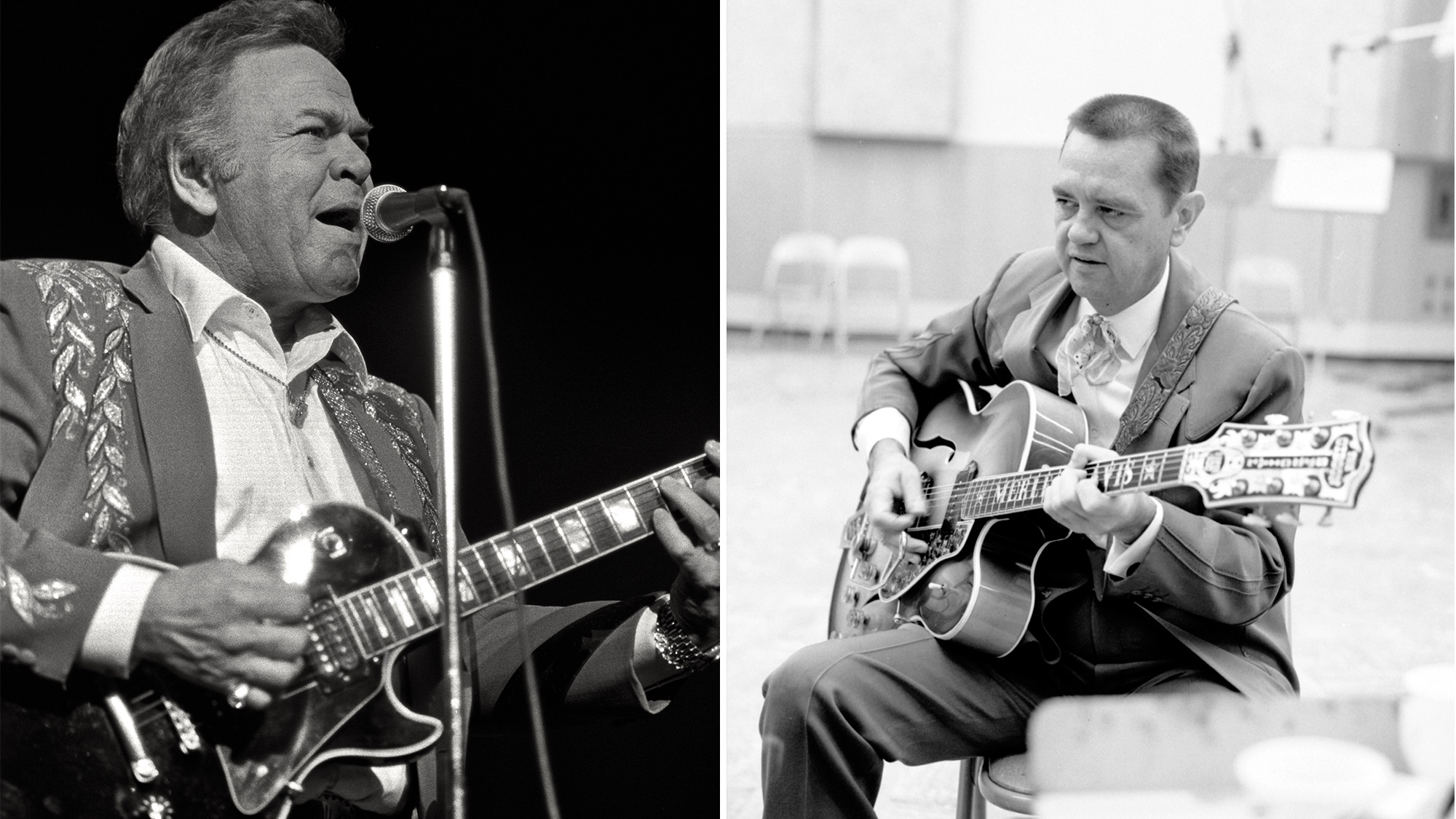

“I said, ‘Merle, do you remember this?’ and I played him his song Sweet Bunch of Daisies. He said, ‘I remember it. I've never heard it played that good’”: When Roy Clark met his guitar hero