Thomas Gabriel Fischer Looks Back on Celtic Frost's Triumphs and Tragedies

“We were too young and too involved to see the greater context of anything,” reflects Triptykon frontman Thomas Gabriel Fischer, looking back on his days with Swiss metal legends Celtic Frost. “We didn’t really think of creating anything pioneering or modern.”

And yet, pioneering they were. Under the name Tom G. Warrior, the guitarist and singer left a lasting scar on the metal landscape, leading Celtic Frost through five albums between 1984 and 1990 before the band finally crashed and burned. (A reunion album, Monotheist, would be released in 2006.)

Despite the indifference—or in some cases, outright antipathy—of the mainstream music biz, Celtic Frost won a devoted worldwide following with their dark, experimental and extremely personal aesthetic. Their music continues to influence extreme metal practitioners to this day, even though Fischer happily admits that he’s not a shredder in the classic sense.

“My entire career is based on expressing my personality through my guitar, but certainly not on being a technically proficient guitar player,” he says.

“It is a completely different approach to guitar playing. I stood there as the young Tom Warrior, with these raging feelings inside of me, of having been an outcast, having experienced violence, having experienced a difficult youth, being completely ignored by the Swiss scene at the time, all of these things—I stood there in our stinky rehearsal room in front of my Marshall, trying to express these feelings.

"I was standing there on my own, trying to figure it out, learning step by step how to do this feedback, how to do this tone, how to express what was inside of me. So that’s a completely different approach than if I’d paid somebody 50 bucks to teach me for two hours where to find these notes, you know?”

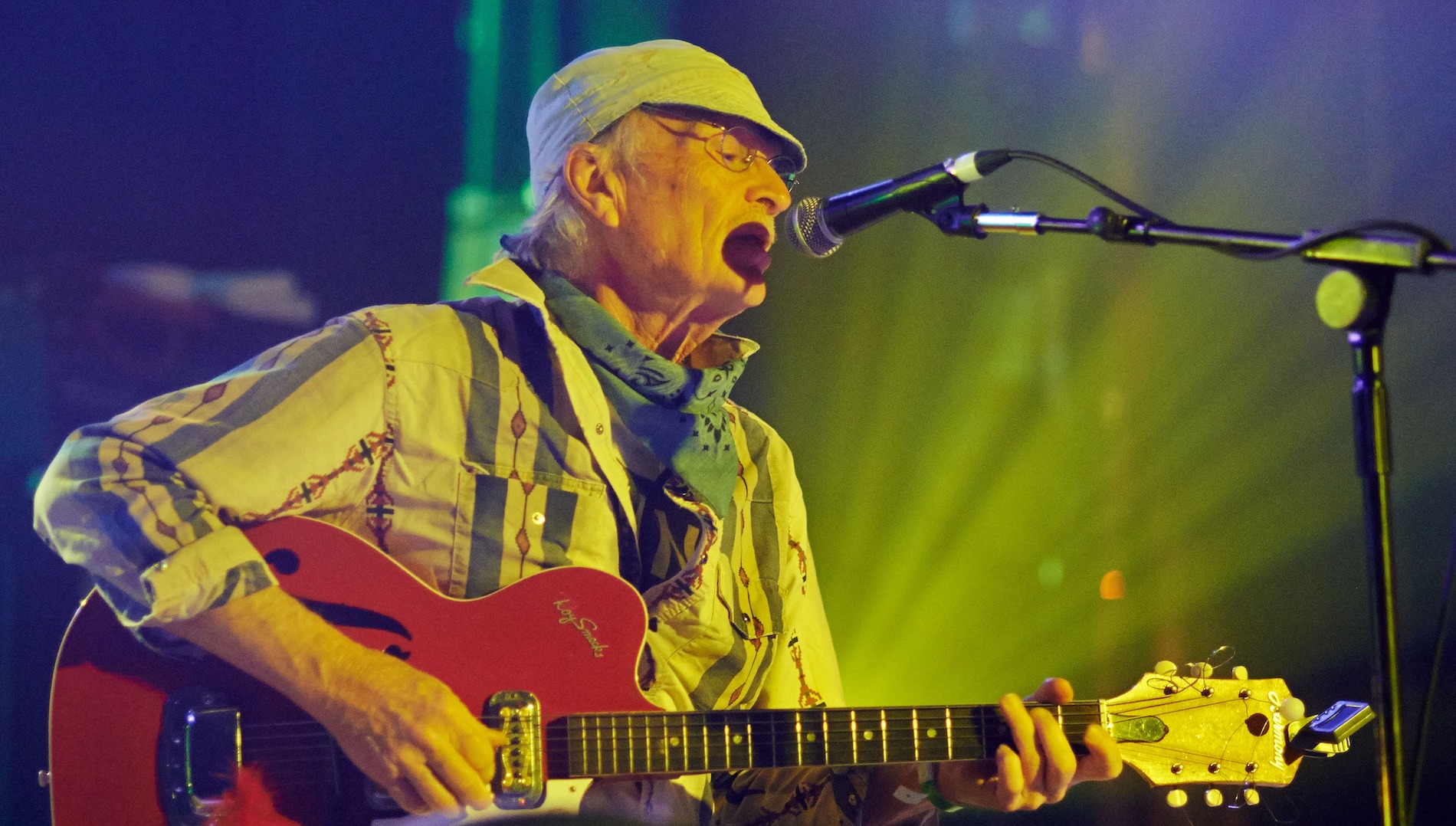

Celtic Frost in the Eighties (from left): Tom G. Warrior, Reed St. Mark and Martin Eric Ain

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Now in the midst of working on the follow-up to 2014’s Melana Chasmata, Triptykon’s acclaimed second album. Fischer graciously took some time out to talk with Guitar World about four of Celtic Frost’s original albums—1984’s Morbid Tales, 1985’s To Mega Therion, 1987’s Into the Pandemonium and 1990’s Vanity/Nemesis—which have recently been reissued in deluxe CD and vinyl editions by BMG/Noise. (1988’s Cold Lake, the band’s notorious glam-metal misstep, was pointedly excluded from the reissue campaign.)

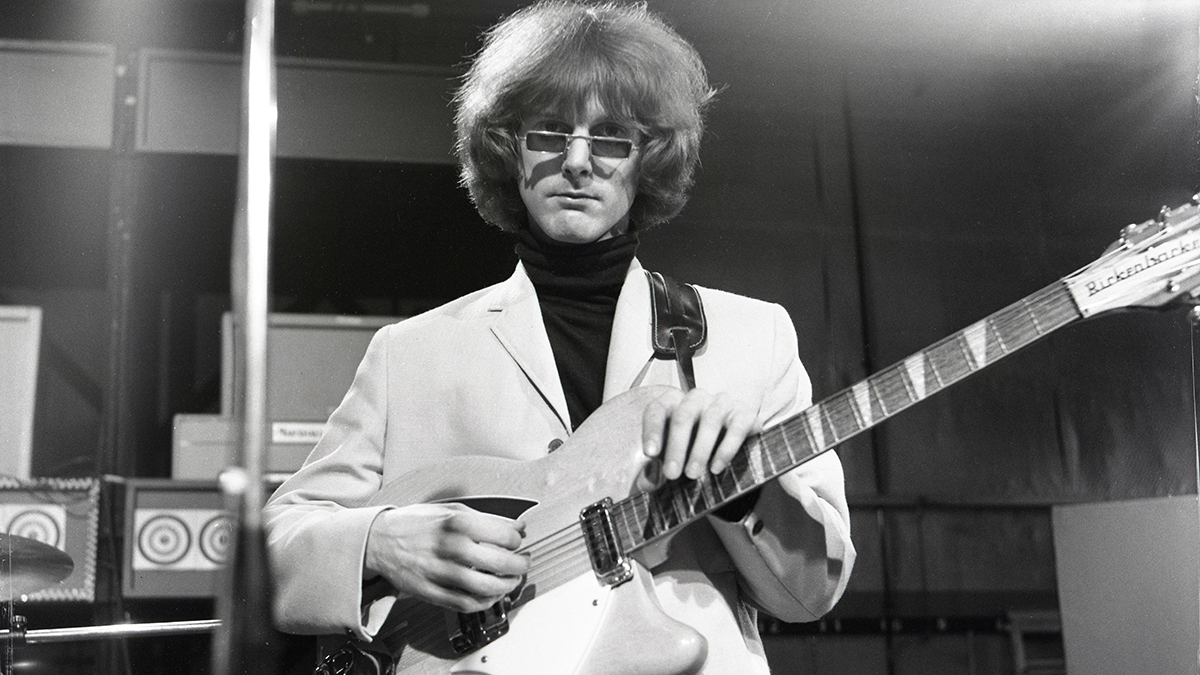

Warrior during the To Mega Therion photo shoot in Zurich, Switzerland, in September 1985

“These albums are all deeply flawed,” says Fischer. “But looking back at them now, I think that’s exactly what makes them so unique. They’re not perfect, run-of-the-mill products…they are experimental albums, and in many aspects they fail; but in a way, that’s a part of it. We were exploring things, and if you explore things, you sometimes have to take the risk of failing. And of course, Celtic Frost failed many times, but I wouldn’t change a thing. I think I learned as much from the failures as I learned from the successes, and it would be way too simplistic and too pretentious for me to just look at the good sides.”

Morbid Tales (1984)

Though it’s now hailed as one of the most important and groundbreaking extreme metal albums of the Eighties, Fischer says that Morbid Tales was primarily driven by a desire to survive the failure of Hellhammer, he and bassist Martin Ain’s previous band. While you can hear the influence of Motörhead, Discharge and Venom on thrashy tracks like “Into the Crypts of Rays” and “Procreation (of the Wicked),” the female vocals of “Return to the Eve” and the eerie noise collage “Danse Macabre” pointed to broader musical aspirations.

“Our only official record at the time, the Hellhammer EP, was criticized heavily by the record company and by the press of the day as being a muddy production, limited technical capabilities, and so on,” Fischer recalls.

“With the ears of the time, at a time when bands strove to have vocalists like Ronnie James Dio, we agreed with these criticisms—we could see where they were coming from. So we abandoned Hellhammer, and we created a new band and recorded Morbid Tales in an attempt to not be dropped by the record company. The album was deeply, deeply personal, and actually a very desperate undertaking, where we put every ounce of our energy into something, because we could only see up to that album; we didn’t have a horizon beyond that. Because we really didn’t know whether we could pull it off…

“We had spent years in a mildewed, wet, stinky, underground rehearsal room—an old bunker—dreaming of attaining a record deal, being fanatical metal fans, literally playing every single day, much more than any other Swiss band that we knew. And then we had attained a record deal, which was the fulfillment of our teenage dreams, and of course we wanted to keep that. We knew our first record with Hellhammer was flawed, and we wanted to show that we were not blind, and that we could actually progress as musicians. And we were desperate not to end back up in that rehearsal room without a record deal. And I think you can hear that fervent energy, that desperation, that determination, that energy in Morbid Tales.”

To Mega Therion (1985)

Recorded less than a year after Morbid Tales, To Mega Therion was a tremendously ambitious leap forward for Celtic Frost. The intense dynamics of tracks like “Innocence and Wrath,” “Dawn of Megiddo” and “Necromantical Screams” not only benefitted from the addition of American drummer Reed St. Mark, but they also took the then-unusual (and controversial) step of adding orchestral instruments—in this case, French horn—to the mix.

“We refused to limit ourselves, to be censored,” says Fischer.

“We left the ordinary society, grew our hair, dressed differently and played music that everybody hated exactly because we didn’t want to be limited. We hated these mechanisms in society where idiots tell you what to do—and then, as soon as you are in a metal band, you are being told what to do? No, not Celtic Frost. I had listened to Emerson, Lake and Palmer or Deep Purple in concert, or early Roxy Music, and I loved the combination of classical instruments with rock music. And I was wondering if we could combine that with extreme metal, and that’s why we did this—even though some people said, ‘You cannot do that, you should not do that, it’s wimpy, blah blah blah.’ Even back then, we simply refused to be contained…

“When you look at it nowadays, I myself am shocked about the timeline—the brief intervals between these individual releases. When we were really young, time seemed to pass much more slowly, and we thought there was an eternity between these recording sessions and albums. But in reality, this all happened incredibly quickly, considering that the very first Hellhammer demo was recorded in June ’83, and a little more than two years later we did To Mega Therion. It’s incomprehensible to me now. But the only explanation that I have is that we were truly extreme; we didn’t just talk about being extreme, or try to appear extreme in photos—we really were extreme. We were absolutely fantatical, and we lived and breathed this music and lifestyle. There was nothing fake about it.”

Into the Pandemonium (1987)

On their first self-produced album, Celtic Frost pushed further into symphonic metal territory, while also cementing their avant-garde reputation by adding industrial and gothic elements to the mix—and making the ballsy and completely unexpected move of opening the album with a cover of Wall of Voodoo’s “Mexican Radio.”

“Martin and I were fanatical metalheads” Fischer explains. “But at the same time, we loved music. Martin came as a huge fan of what was then called new wave—bands such as Bauhaus, Sisters of Mercy, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Joy Division, what have you. I loved that music, too, and in addition I loved jazz music, I loved classical music, I loved experimental rock music, and so on. And when the two of us combined all this, and then we found a drummer like Reed St. Mark, who also came from a jazz background, a Latino background, and so on—the creativity in the band was limitless. And we wanted to use that!

“But when it came to the Into the Pandemonium album, the record company actively tried to prevent us from doing this. They threatened to shut down the production, and they told us literally to record an album like Slayer or Exodus. They said, ‘That’s what’s selling. What you’re doing will not sell a single copy!’ Nowadays, every metal band has worked with classical instruments, with female singers; there’s tons of gothic metal bands, it’s a household thing. Back then, it was completely unheard of, and everybody tried to stop us. Nobody could see the merit in it. And also, we didn’t only have to fight objections; we also had to fight inexperience.

"The engineers had only recorded thrash metal, bands like Sodom or Destruction; they didn’t have any experience in how to record a horn or cello. So it was experimentation every step of the way, and it was the overcoming of all kinds of obstacles every step of the way. It wasn’t very easy to create these albums, but I think that, too, adds to the reality, the desperation, and the emotions you hear on the albums.”

Vanity/Nemesis (1990)

Celtic Frost’s final album before their breakup, Vanity/Nemesis was an attempt to pick up the creative thread that they’d dropped following Into the Pandemonium. Produced by electronic/industrial whiz Roli Mosimann, the album contains some deeply affecting moments, like “Wings of Solitude” and a cover of Bryan Ferry’s “This Island Earth,” though it lacks the overall sense of vision and drive that had powered the first three Celtic Frost LPs.

“It was too little, too late,” Fischer reflects. “To be honest, in my opinion nowadays, I think the band was shot. Vanity/Nemesis, it’s just a generic metal album. I guess after Cold Lake, we were scared of doing any more experiments. We had done four albums of sometimes radical experiments; three times it had worked, and one time we fell flat on our faces—and rightly so, of course. But that left us basically impotent; the essence of Celtic Frost—namely, being daring—was completely gone, and the band chemistry was gone. We still tried to record an album, and at the end we thought we had done a commendable job.

"Now I think it’s a failure of an album. It’s better than Cold Lake, but then so is a toilet at a music festival! [laughs] “The first three Celtic Frost albums sound according to their time—they’re mid-Eighties extreme metal albums—but you don’t listen to them and think, Oh, they sound old.

"For some reason, they’ve aged very well. But you listen to Vanity/Nemesis, and you can hear that it is also a product of its time, but to me it sounds outdated and tired. To me, that’s the huge difference. And that, to me, shows that the band had completely lost the plot, as it had on the album before it, of course. If I had been the person that I am now, I would have ended things one and a half years earlier. But live and learn, I guess.”

“There’d been three-minute solos, which were just ridiculous – and knackering to play live!” Stoner-doom merchants Sergeant Thunderhoof may have toned down the self-indulgence, but their 10-minute epics still get medieval on your eardrums

“There’s a slight latency in there. You can’t be super-accurate”: Yngwie Malmsteen names the guitar picks that don’t work for shred