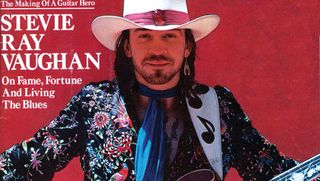

Stevie Ray Vaughan Discusses Fame, Hendrix and His New Album, 'Soul To Soul,' in 1985 Guitar World Interview

Here's Guitar World's second interview with Stevie Ray Vaughan, from the November 1985 issue. The original story by Bruce Nixon started on page 28 and ran with the headline, "It's Star Time: Stevie's been in the spotlight so long now, he's just beginning to realize — with the help of Clapton, Townshend and Albert King — that everybody's eyes are on him."

Something was up. Stevie Ray Vaughan looked like the cat that swallowed the canary.

He had plenty of reason to be pleased, of course: A few weeks earlier, Vaughan and his band, Double Trouble, had received their first Grammy (in the ethnic music category, for some tunes on a Montreux Jazz Festival blues anthology), capping a year in which they'd won a number of other industry awards.

After seeing their first two albums climb into the upper reaches of the charts, they'd toured widely at home and abroad and were, at that moment, in the midst of finishing up work on their third record, Soul To Soul.

But something more than a year of new triumphs and successes was on Stevie Ray's mind, and he was being deliberately and playfully vague. Nothing arouses your curiosity faster than that. He positively seemed to glow.

Was he born again?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"Something like that." There was the faint wisp of a knowing smile under the broad-brimmed hat. It was a white hat, too-not the black Man With No Name hat that's become a trademark of sorts.

Quit drinking and smoking?

He held up his glass. "No."

Make up with his wife and family over something?

"That's part of it."

Vaughan grinned mischievously, and talk moved in other directions. He was sitting in the dim corner of a lounge in a pleasant North Dallas hotel, waiting to leave for the studio where Soul To Soul was coming down the home stretch. A little later, the rest of the band came down — drummer Chris Layton and bassist Tommy Shannon, an alumnus of the old Johnny Winter band of the sixties — and they clearly possessed something of the same glow. Was this contagious?

"Yeah, some big changes have taken place. I haven't resolved all my problems," Vaughan finally explained, "but I'm working on it. I can see the problems, at least, and that takes a lot of the pressure off. I've been running from myself too long, and now I feel like I'm walking with myself."

During the course of a long conversation, there had been hints of friction in his organization, a sense of the many unpredictable pressures that had been placed on the band, but Vaughan was referring to something else entirely. There's sometimes been a feeling, yes, that Stevie Ray Vaughan was uncomfortable with his success, perhaps a bit bewildered by it — why should fate tap him, a humble blues guitarist? — or, at least, he was not totally prepared for its accompanying responsibilities. He was confused by the people who were drawn to him because of his success and not because of him or what is in his music.

Despite all that's happened to him during the past two years or so, Vaughan possesses not so much as the slightest aura of rock stardom. He seems very much the hard-working club player he used to be, friendly, modest, down-to- earth.

He chuckled at the memory of playing Austin clubs years ago, making a few dollars for the night and then borrowing money from the bartender to cover the bar tab — he laughed remembering it that $1.36 was the least he'd ever earned on a paying gig. But now, the success is there just the same, and at some point, he finally began to reach an understanding of it all. He's getting used to the attention, the star-gazers and the paparazzi.

Vaughan remained vague about some of the particulars — it was an element of privacy he seemed to be reserving for himself — although he was quite amiable, and talked at great length about his current album and about some of his plans for the immediate future. He was very excited about the new Lonnie Mack album just about to hit the streets at the time of the interview, an album he co-produced in Austin last year, and on which he played.

He'd picked up a few important life lessons from the veteran guitarist: Mack, of course, has seen it all and done it all in his long career, and lived with success and without it, and he still plays up a storm.

"He's getting younger all the time, too," Stevie Ray chuckled. "I swear he is.' Look at him reeeal close." He smiled: "I sat down and talked to the man, and he's one of the men who will sit down and talk to you, too. And thank God for that. He's a wonderful cat. He opened my eyes to a lot of things."

While Double Trouble was touring in Australia recently, the band crossed paths with Eric Clapton, another player whose work reflects very personal, quest-like grapplings with the accouterments of success.

"He didn't tell me what to do," Vaughan said. "He told me how it'd been for him." Afterwards, Clapton and Vaughan had holed up in a hotel room for a few hours, talking about success and its pit falls. Vaughan didn't want to elaborate on exactly what was said, but it was clear that Clapton's wisdom involved star qualities Stevie had to acknowledge in order to deal with them.

"Then we were working with Albert King, and he came up to me, and he said, 'Man, we got to sit down and have a little heart-to-heart. You sit down like that with Albert King and you grow.'"

And Vaughan remembered something that came from Johnny Winter, who'd preceded him down the long path, the first white Texas blues guitar hero.

"He said something to me when the first record was doing so well," he recalled. "It made me feel a lot of respect for what we did, for the music. He said that he wanted me to know that people like Muddy Waters and the cats who started it all really had respect for what we're doing because it made people respect them. We're not taking credit for the music. We're trying to give it back."

A few weeks later, when I talked to Vaughan again, he elaborated on his relationship with Albert King. It was almost midnight, a warm Dallas spring night, and we were driving across the northwest part of the city looking for hamburgers while rough mixes of the new album played on the tape deck.

"Albert calls me his godson," Vaughan said. "He'll look at you and talk to you, that's the thing. He's pleased with what we've done, and he explained some simple things-don't get high when you're working 'cause you're having too much fun and you don't see the people fuckin' you around. Have fun — that's great-but pay attention. That happened when things were happening so fast, and it was real important to hear that kind of stuff. He knows. He's been through it. You wake up one day back in the clubs without a whole lot to show for what you've been through.”

Sitting in the car, while a waitress brought trays of burgers and beer — an old Texas all-night drive-in, the only thing left open — Vaughan added that he planned to produce a new album for Albert King on the recently reactivated Blue Note label, and that they hoped to cut it in Austin. Talk turned back to Lonnie Mack.

"He's something between a daddy and a brother," Vaughan explained. "When he sees something that needs to be talked about, he'll talk. He understands. He's deep, real deep, and a warm kind of deep. He wanted to produce us a couple, three years ago, but it didn't happen then, of course, and things just worked out like they have. The way I look at it, we're just giving back to him what he did for all of us. It wasn't a case of me doing something for him-it was me getting a chance to work with him.

"You know," he added, "the way people come into your life when you need them, it's wonderful and it happens in so many ways. It's like having an angel. Somebody comes along and helps you get right."

So things are coming together. Vaughan, Shannon and Layton together, talking about the new record, could scarcely contain their excitement. A lot of people have wondered how far yet another Texas guitarslinger could carry the blues thing, and Vaughan has attempted to formulate an answer. He wanted to make a happy record, he said, full of buoyant moods. Shorter songs, less heavy breathing from the guitar, some new instrumental combinations. On Soul To Soul, you hear a lot of the Stevie Ray Vaughan trademarks, but it still has a good-time, uptown feel — a strong trace of R&B — that separates it from Vaughan's first two albums. The guitar showpieces are there, but it's clear that Vaughan set out to accomplish something different with this record.

"I'm real close to it, and so it's hard to get a good perspective on it," he said, "but there're a lot of rockin' songs and then some like we've never played before. There's definitely blues in it — not less blues than before — but it's a type of music we haven't really tried before, some different kinds of changes. There are a few other players here and there that people won't expect, some keyboards [ex-Delbert McClinton ivories-tinkler Reese Wynans has been added to Double Trouble. -ed.] some horns. But the moods are happier."

At that particular time, the band was working nightly at Dallas Sound Lab, a 48-track digitally capable facility in the Dallas Communications Complex at Las Colinas, just northwest of the city. They'd booked the studio in great 24-hour chunks of time, and had even recorded rehearsals, and Vaughan was finding those sorts of conditions pretty luxurious — one of the benefits of having two successful albums under his belt. It helped shape the character of the music on the new record.

"It's helping a lot," Vaughan explained, "because we've gotten to work on individual technique and things, so that we've come down to playing more like we wanted to play in the first place. To do that, we had to cut in the studio and sit down and listen to it. We've always been forced to work a lot faster than this before, and we play so many gigs on the road that we don't have the time to listen to ourselves as closely as we should all the time. You go and play for an hour and a half and then go to the next place, and you don't get a chance to catch what's changing in your music, what's working and what's not working. We love to play shows — don't misunderstand me on that-but it's hard to ask how did we improve, or did we? We have fun when we play, but the studio is a blessing that a lot of people forget about, maybe.”

He said that they were recording the album the "old way," live, in the same room together and without headphones. "I've got every amp I own in the studio and all going all out at once," Vaughan laughed. "They had to build a new monitor system for us." The studio, he explained, was set up like a stage, but with the amps aimed in such a way that the other players could hear what was coming out of them. Vaughan even played drums on one cut, but it was too slow, so the song was speeded up to raise its pitch a half-step.

"We're recording the old way and using the best modern equipment we can find, and it's a good combination," Vaughan said. "We go in and cut a song a few times if we need to, or just do a set. At this point, we're pretty fine-tuned, and we're watching it grow as it goes. We're all looking at it, and we have a lot of ideas, things we've wanted to have a chance to work with."

Double Trouble had toured for 18 1/2 months prior to the release of Couldn't Stand The Weather in 1984, and then they took two months off before starting a new project. "We didn’t realize how hard it was to just go cold, without playing in front of people again. I'd never thought about that before. We'd rehearse — try to play this and that but we didn't play in front of people. You 'd be amazed how hard it is not to play in front of people."

In any case, you don't get the sense that a lot of career planning goes into a Double Trouble album — no big calculations about how it should sound or how many units it should sell. It mainly charts the natural growth of Vaughan and the band. "We're trying for feeling. We try to accomplish something with the music, which is to feel through things. I've been trying to grow up some myself, in my heart, and it's happening quick and I feel good about it, and I want that to come out in the music."

Meanwhile, Vaughan remains — like a lot of Texas guitarists — a die-hard Stratocaster player who uses a minimum of effects. Working on the album, he's stuck mostly with a white Strat-style guitar with Danelectro pickups and custom wiring that was made for him in 1983 by the late Charley Wirz, a Dallas guitar dealer, builder and repairman who was a close friend of Vaughan's for many years. It's the instrument Vaughan's holding on the cover of Couldn't Stand The Weather, and a perfect example of its sound is the light, quickly strummed break in "Tin Pan Alley," which was recorded with only a low Leslie effect.

On the back of the guitar, a simple message is engraved on the metal plate where the neck joins the body: "To Stevie From Charley. More In '84." It's rather characteristic of the generous spirit that Vaughan's early success inspired in many of his old Texas fans — and, indeed, Soul To Soul is dedicated to Wirz.

"I've been going between that guitar, the beat-up '59 Strat and this other guitar that Charley found for me, a '61 Strat. It's brutal. They all have that neck, and I associate them with Charley — I didn't get the '59 from him, but he worked on it so many times that it feels like I did, I guess. I like the white ones. It sounds like my old beat-up one, but it's cleaner, not quite as full-sounding. And Charley never told anybody but me what he did when he wired it.

"But that's the sound," he added, "that Leslie and that guitar, if the amp's working clean. You have 'to use the right amp, like a Super, that with the Leslie and a Vibraverb head — it's really a steel guitar head-if you set 'em all up in a live room, it sounds great. I don't use a chorus — I like to get that sound with a Leslie, too. It's old-fashioned, but I'm trying to bring it up-to-date."

Vaughan 's pretty vague about his amp set-up, although he admits to keeping two Vibraverbs, two Super Reverbs, a Dumble 150-watt Steel String Singer (which he had stopped using for a while, but brought back into service recently) and the Leslie all hooked together. The actual combination, he explained, was determined over a period of time by which amp worked when, until he accidentally evolved a combination that he liked. Other amps seem to come and go-indeed, in the several weeks between interviews, he'd acquired another Fender.

"They're hooked up pretty straight, I guess," he grinned. "I have a Tube Screamer, a wah and the Leslie on my pedal board, and an on-off switch for everything, so that when I switch it off, between the guitar and amp there ain 't nothin'. When I do a song like 'Third Stone From The Sun,' I can't control the feedback with the effects on. It goes crazy, so I switch 'em all off and then kick it back when I'm done. It's mostly straight, though — a weird set-up — but pretty straight."

In addition to that, he continues to play with his guitar tuned a half-step low-"E-flat tuning" he calls it — and he said that before Wirz died, earlier this year, they had discussed building a custom-scale neck that would allow Vaughan to play the tuning without transposing with concert-pitch instruments.

It sounds like an impossible idea, but who knows? When two stone guitar fools like Stevie and Charley got together, anything was possible.

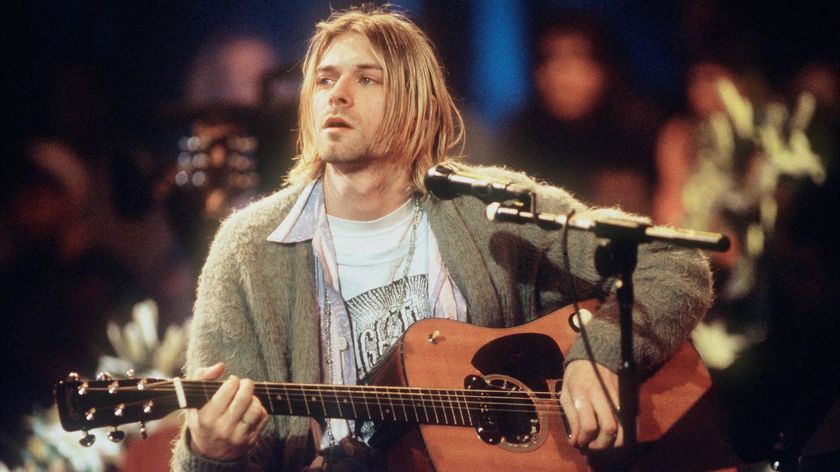

The use of the low-pitch tuning was Hendrix-inspired, in any case. "He did it a lot," Vaughan said, "and it gives you different overtones. It's an interesting sound, and I find it a lot easier to sing to." He's also acquired the wah-wah pedal that Hendrix used to record "Up From The Sky."

Vaughan talks without any self-consciousness about Hendrix, but comparisons between the two players have been made often enough. In May, Vaughan opened the Houston Astros' season with a solo version of "The Star-Spangled Banner" and, immediately, people remembered the world-weary, apocalyptic version that Hendrix played on the final day of Woodstock in 1969.

Vaughan flashed a look that clearly regarded the issue as unbelievably dumb and unnecessary. "I heard they even wrote about it in one of the music magazines," he said, "and they tried to put the two versions side by side. I hate that stuff. His version was great." Vaughan's was the first time that someone had played electric guitar to open a baseball game.

"Why do people want to make it out to be more than it is? I can't stand these comparisons." He wasn't speaking angrily, either. He hadn't even raised his voice. This seemed to be the musician in him talking, matter-of-factly, making an obvious point.

And yet, the comparison exists — if only because Vaughan includes at least one or two (and sometimes three) Hendrix songs in each live show, because he featured a well-known Hendrix song ("Voodoo Chile") on his second album, and, perhaps most of all, because he captures the spirit of the improvisational Hendrix on stage more accurately than any other contemporary guitarist.

An affinity obviously exists. In Texas, Vaughan's regarded by his old crowd as a hot blues player with a tight band and a lot of rock and roll in his sound: the blues variations are still common in Texas clubs. His music has been refined and expanded by all the work and the opportunities that've come his way in the past two or three years, but at its core, it's still the steamy, torrid blues he was playing in the late seventies. The people outside Texas, really — the ones less familiar with his story and the ones who know his work only from records and the hype of the last few years — have turned Vaughan's long-standing love for Hendrix' work into a point of comparison. Vaughan himself feels it's all been overplayed.

According to one person in his organization, Vaughan labored long and hard over the decision to add "Voodoo Chile" to Couldn't Stand The Weather, and that he finally decided to include the song because he felt that the younger audience that was listening to his records hadn't heard Hendrix, and he wanted to spread the word.

"I loved his music and I feel like it's important to hear what he was doing, just like anybody else, like Albert of B.B. or any of that stuff," Vaughan remarked. "I wanted to do the song, but I didn’t 't want to mistreat it. I feel like, I try to take care of his music and it takes care of me. Treat it with respect, not as a burden- like you have to put a guy down 'cause he plays from it. That's crazy. I respect him for his life and his music."

Meanwhile, in a Dallas show in late April, Vaughan used the Wirz Strat and the '59, and a custom Hamilton occasionally when a string broke on the '59 Strat. On slow blues like "Tin Pan Alley," the white guitar had a thin, edgy, cutting sound, sweet but hard: the '59 Strat is a fuller, chunkier-sounding guitar, more of a rocker, more typical of the thick tones on Couldn't Stand The Weather, and, of course, the instrument of choice when Vaughan does his Hendrix covers.

While they weren't airing a lot of new tunes that night -- it was a free concert with Lonnie Mack in front of a hometown crowd — Double Trouble was debuting a new keyboard player, Reese Wynans. Wynans, of course, appears also on Soul To Soul. Vaughan himself played beautifully that night: his slow blues remain gorgeous displays of phrasing and tone, and, of course, he has a growing arsenal of tricks and techniques, from his flowing, syncopated strum ("Pride And Joy") to funky, overstated string-snapping effects. In the past two years, he's learned a lot about working an audience, as well. In the clubs he often was a straightforward, stand-up player, but he's become a good showman, too.

"When we started making the album," Vaughan said, "we thought about what kids do during the summer. I was remembering the good times, how things were when we were growing up, and the good songs would come on the radio and go boom inside your head. Getting that passion- that's what I try to do."

In late April, within days of the Dallas date, the new Lonnie Mack album on the Chicago-based Alligator label, Strike Like Lightning, finally hit the stores, the first record from the legendary guitarist in some seven years. While Vaughan downplays his role as co-producer — it's his first production effort outside Double Trouble — it's clear enough from the handful of guitar duels included on the album that Vaughan and Mack were having a grand time, and Vaughan mostly helped contribute the spirit and enthusiasm that ultimately made for a heck of a guitar album. Vaughan, of course, has always acknowledged Mack's influence on his own playing — "Wham!" was the first single he ever owned — and the two hit it off wonderfully when they finally began working together. The empathy and interplay is obvious.

Vaughan remembered the first time he met Mack. It was 1978 or '79, and an earlier version of Double Trouble (with Layton) was playing in a club in Austin when Mack walked in. "I was playing the second chord of 'Wham' that night when he came through the door," Vaughan said. "We did the shit outta 'Wham! It was cookin'. And there was Lonnie Mack. At first, I didn't even recognize him. Man, it was like magic."

At the time, Mack was assembling a new road band, and he approached Vaughan about joining it. That never came to pass, of course, but the two remained friends over the years: when Alligator signed Mack in mid-1984, Mack and Alligator president Bruce Iglauer talked to Vaughan about producing the record and he agreed instantly.

"They were his tunes and I just tried to help him by doing the best I could to do what he wanted to do with the record, and that's what I think producing is," Vaughan said. "A lot of producing is just being there, and, with Lonnie, just reminding him of his influence on myself and other guitar players Most of us got a lot from him. Nobody else can play with a whammy bar like him — he holds it while he plays and the sound sends chills up your spine. You can't do that with a Stratocaster. I just don't want to sound like I was trying to direct the record. We were having fun and it was a great experience. It makes you think, too. This whole thing was a blessing, and it's not over yet. "

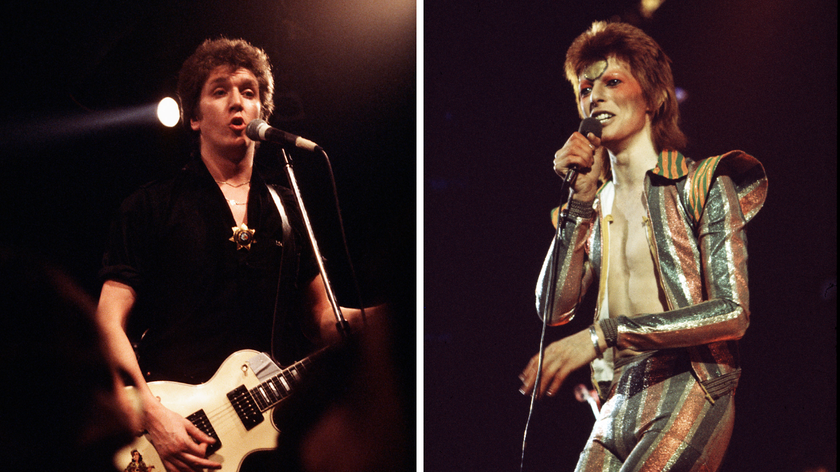

In any case, things are moving pretty fast, but there 's a feeling, at least on Vaughan 's part, that this is only the beginning. The beginning wasn't playing on David Bowie's Let's Dance, which helped showcase his work to the greater rock and roll public, or the first album, whose performance on the charts seemed to surprise just about everyone because it was atypical of the pop moods at the moment. The beginning is now — this new attitude, the self-sustenance and self-reliance, the sense of faith in the future. What Vaughan stands to accomplish, perhaps, is an important service to the blues — blues is widely enough recognized as the foundation of rock and roll, but Vaughan may have the opportunity to bring the blues back into the current mainstream of rock in new ways, at a new level. He may, in fact — as Albert King has suggested — take the color out of the blues.

"I do feel as though I have grown as a player through all this," Vaughan remarked at one point. "It's funny — I 'm trying to get back to how I used to play years and years ago, but, at the same time, make those ideas grow, tie them into what we're doing now. I guess I'm just remembering where all these things come from. It's all pretty regular music to me, what I've heard all my life, what I grew up with the Glory tunes, Johnny G. and the G-Men -- I used to hear some of those old bands in — Dallas, at the Heights Theater in Oak Cliff, in '62 and ‘63.

"Now, I use heavy strings, tune low, play hard, and floor it." He laughed. "Floor it." Another chuckle. "That's technical talk."