Five years ago, alternative-rock fans were ecstatic when the pioneering feminist punk trio Sleater-Kinney called off their nine-year hiatus and released their most raucous and diverse album to date, No Cities to Love.

Fast-forward to 2019, and the group has made even greater stylistic leaps on a brand-new disc, The Center Won’t Hold. Days before the album’s release, however, co-founding guitarists Corin Tucker and Carrie Brownstein were stung by the surprise news that longtime drummer Janet Weiss was packing it in.

We asked Janet to stay, but she said, ‘I'm definitely leaving.’ We're just kind of moving ahead in terms of how we're going to play this album for people so they can hear it

Corin Tucker

Both players are loath to discuss the reasons behind Weiss’ departure, but when pressed, Tucker says, “We asked Janet to stay, but she said, ‘I'm definitely leaving.’ We feel like her drumming on this record is great. We're really proud of the work we've done, and we're just kind of moving ahead in terms of how we're going to play this album for people so they can hear it. As for anything more on that, I think it’s for Janet to say.”

The famously political group doesn’t shy away from current events on the new album. Indeed, the harrowing title track explores what Brownstein calls “the fractious and tumultuous period we’re in leading up to the next election.”

But she’s also quick to point out that many of the tracks carry multiple meanings. “Some of them could be seen through a political lens,” she says, “but at the same time they spread out and deal with deeply personal issues, through various iterations of fragility. You can react to them how you want.”

While Tucker and Brownstein’s famed twin-guitar/no-bass approach is still evident throughout The Center Won’t Hold - sparky, fuzzed-out guitar riffs and snappy yet lyrical solos abound - songs such as Reach Out, Hurry on Home and Love gurgle with the sounds of synth and electronic underpinnings.

Brownstein credits producer St. Vincent (aka Annie Clark) with this radical change to the band’s sonic palette.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“One of the biggest reasons we wanted to work with Annie was because of her prodigious imagination and her desire to be innovative,” she says.

St. Vincent presented us with a new toolbox and showed us a way we could reconfigure our sound

Carrie Brownstein

“She challenged us on multiple levels, embracing our methodology while re-assessing our strengths. She presented us with a new toolbox and showed us a way we could reconfigure our sound. A lot of times, what you think are guitars are keyboards and vice-versa.”

Tucker also gives St. Vincent high marks (“she’s daring and amazingly talented”), but she stresses that the shift in Sleater-Kinney’s instrumental approach began in the early writing stages for the new album.

“We were making full demos and trading files back and forth,” she says, “and I think that process opened us up to exploring different instrumentation. When you write on a computer, it’s different than when you hold guitars in a rehearsal room. So we weren’t caught up in one sound; we were sort of un-married to how a song should take shape in the studio, and we were ready to try anything.”

There have been many great groups without a bassist - the White Stripes, the Black Keys, and of course, we can go back to the Doors. I’m curious, though - did you ever felt confined by the setup?

Carrie Brownstein: "No, I think limitations help create innovation. When your band has a lexicon, you sort of figure out how to expand that vocabulary.

"Corin and I forced ourselves to think about the guitar and its tones - the low-end vs high-end - and that was because we didn’t have a bass player or somebody playing keys to augment our two guitars. Our limitations allow us to go somewhere new, as in the case on this album where we said, 'Time to bring in new elements.'"

Carrie, you seem to be more of the lead guitarist, while Corin, you tend to hold down the rhythm. Did the two of you actually map out how you would play together and complement each other?

I do more of the rhythm thing and Carrie is a lead player. And she’s a great lead player, so I never wanted to compete there

Corin Tucker

Corin Tucker: "It wasn’t as predetermined as that. It was pretty organic, really, and it evolved over time.

"Like you said, I do more of the rhythm thing and Carrie is a lead player. And she’s a great lead player, so I never wanted to compete there. Our skills just seemed to fit, and we didn’t want to mess that up.

"We never really talked about it, though. It’s kind of like any relationship where things just work - you know things click, so you don’t question it."

Are the types of guitars you play important to your individual styles and sounds? Did you ever discuss that aspect of your music?

Brownstein: "Not really. I started with a lot of Gibson SGs. I had a 1972 SG that was my standard go-to guitar for many years. I like the playability of it. SGs are light guitars, and they’re very malleable - the necks, the fretboards.

"But lately I’ve been playing guitars made by Reuben Cox - he works out of a store called Old Style Guitar in LA. He made me a couple of guitars similar to Thinline Teles, but he made them sound like Gibsons; they’re thicker and more rubbery. And because they have almost hollow bodies, they sound very alive on stage."

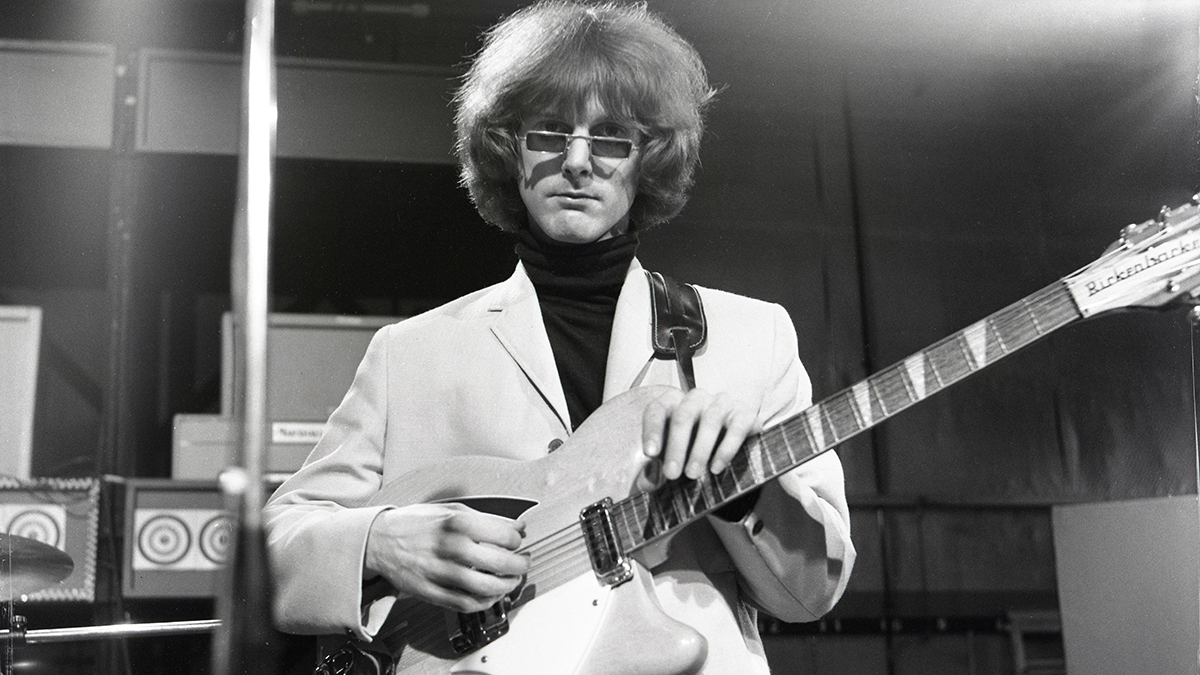

Tucker: "My main guitar is a Gibson Les Paul [Special], and I love it. I definitely play that on this album, but I also use one of the Rickenbacker 325 John Lennon reissues. It’s really cool because it has flat-wound strings on it, which are almost dead-sounding - very good for rhythm playing. Overall, the guitar is very bass-like. It’s a good match to the guitars that Carrie plays."

Do you two ever get into ruts with your guitar playing? Do you find that you tend to play the same patterns over and over, and if so, how do you break out of that?

On this record, I often transposed keyboard and synthesizer parts to guitar parts, and that just made them feel different

Carrie Brownstein

Brownstein: "I think one thing that's been helpful is writing guitar lines on other instruments. On this record, I often transposed keyboard and synthesizer parts to guitar parts, and that just made them feel different - even though you’re dealing with the same number of notes and the same scales.

"Different sounds always help. You try out a bunch of pedals and see what that does to you. Even if you don’t use the pedals on stage or on a record, they might force you to play in a new way."

Tucker: "Or you can put down the electric and play an acoustic."

Brownstein: "Right. I’ll pick up an acoustic, and it’ll sound so different and refreshing after playing the electric for so long. Just get a new perspective, however you do it. Whatever you do, don’t sit around playing the same thing the same way, because yeah, then you’ll get in a rut."

How do you two come up with riffs? On the song Hurry on Home, there’s a main riff, but there’s an answer riff underneath it that’s just as important.

Tucker: "We will trade off lines sometimes, but on that song I think I’m holding down the rhythm and Carrie is playing the guitar lines - our typical way of working.

"On this record, though, we tried not to get caught up in protocol; it’s a completely different methodology. I’m sometimes playing Carrie’s parts, or she’s playing some of mine. We didn’t want to be too attached to something we’d written and played a bunch of times. That keeps stuff sounding fresh."

Songs such as Reach Out and Love have guitar textures and production sounds that recall early-'80s new wave. Was that always the plan, or was that the result of Annie’s influence?

Brownstein: "That was always the plan. On Love, I had the riff that basically takes us through the entire song. When we figured out the chorus, I found it very reminiscent of the B-52s, so that’s when I said, 'OK, maybe the guitar line should be a little more '80s.'

"I think I was always headed in that direction, though. When I first played the main riff for everyone, we were kind of thinking Devo. And then on Reach Out, there was something so anthemic about that descending guitar line and how it reminded us of U2 from the '80s era, so we just went for it. We didn’t want to deny the essence of the song."

Restless is a wonderful ballad that’s built around minimalist guitar playing. It almost sounds out of place amid all of heavy production on the record.

Brownstein: "'Out of place'?"

Well, let’s say it stands out.

Brownstein: "Yeah, it stands out. I really like its stripped-down quality, and I think it fits well on the record because of how it sounds - we’re giving people’s ears a break.

When I picked up the guitar and wrote Restless, it was like I reconnected with the instrument

"Actually, that song started out as a reaction to everything else we were doing. Because we had so much going on with synths and keyboards, when I picked up the guitar and wrote Restless, it was like I reconnected with the instrument. It’s like what I was saying before about breaking out of ruts."

Annie, of course, is no slouch on the guitar. Did she play on the record?

Tucker: "She did. There’s some really cool Annie guitar bits in different places. We wouldn’t not have her on the record."

How are you going to re-create these songs live? Have you given any thought to that yet?

Tucker: "It’s going to be a process, and we’re just now starting to figure that out. We’re fortunate to be playing with [multi-instrumentalists] Toko Yasuda and Katie Harkin, and we’re going to add additional musicians to help us re-create the sound of the album. It should be fun."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“There’d been three-minute solos, which were just ridiculous – and knackering to play live!” Stoner-doom merchants Sergeant Thunderhoof may have toned down the self-indulgence, but their 10-minute epics still get medieval on your eardrums

“There’s a slight latency in there. You can’t be super-accurate”: Yngwie Malmsteen names the guitar picks that don’t work for shred