Scary Good: Ghost's Tobias Forge Breaks Down the Brilliant New 'Prequelle'

It’s been an eventful past year, to say the least, for singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Tobias Forge.

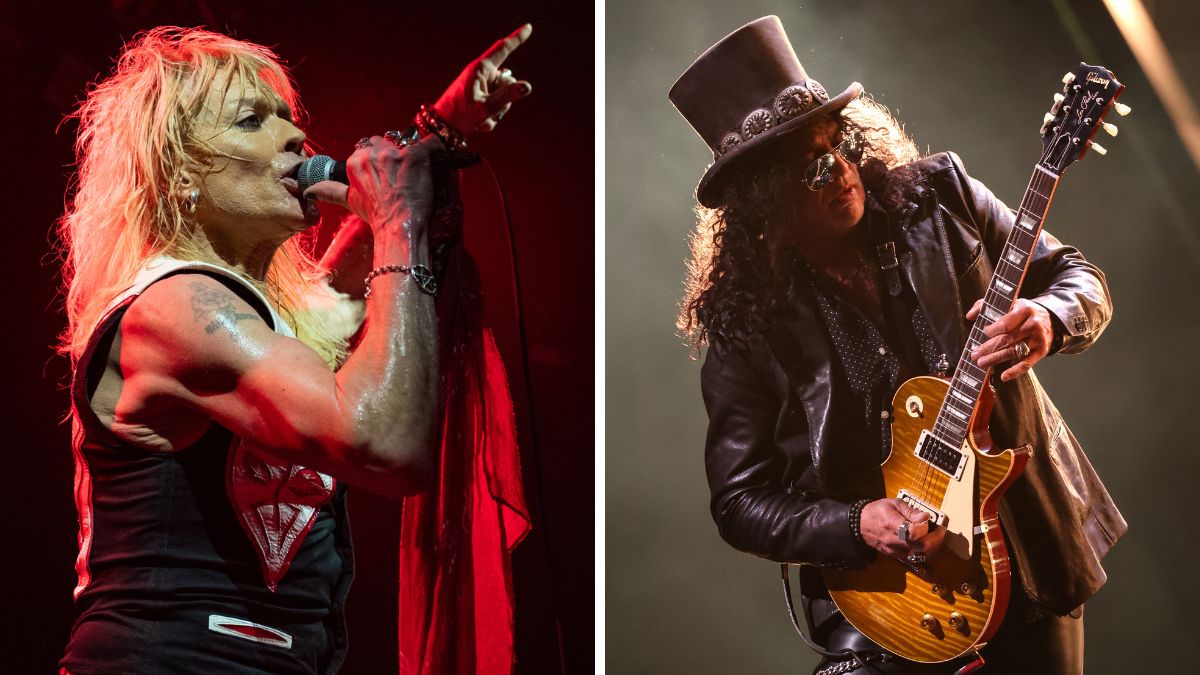

Up until recently, his band, Swedish occult-rockers Ghost, had been operating under a shroud of secrecy, with the multiple masked instrumentalists referred to only as Nameless Ghouls, while Forge, as frontman, assumed the role of Papa Emeritus (and Papa II…and Papa III), a sort of anti-Pope.

Over the course of three albums, Ghost rose to become one of metal’s hottest bands, with successful records (2016’s Meliora hit the Top Ten on the Billboard 200) and sold-out tours, multiple awards (including a 2016 Grammy for the Meliora track “Cirice”) and a worldwide fanbase that includes the likes of Dave Grohl, Phil Anselmo and the members of Metallica.

But in early 2017, the anonymity that seemed so vital to their story and music got stripped away when four former Ghouls filed a lawsuit accusing Forge of financial misconduct. As the suit became public knowledge, so did the identities of the parties involved, revealing Forge as the mastermind of the operation.

But rather than harming the band, this public unmasking seems to have only made Forge stronger. In addition to a new Ghost album, the excellent Prequelle, Forge (now in the guise of new frontman Cardinal Copia) and a new group of Ghouls are back out on the road, and the stages and theatrics have only grown bigger. Rather than pulling back, Forge has regrouped and redoubled his efforts.

“That was the point all along,” Forge says, speaking to Guitar World the morning after a show in Chattanooga, Tennessee, on Ghost’s U.S. headline tour—their first ever in arenas. “I mean, I am following my plan that I’ve had years before any of those guys were in this. So why would I change? That would be stupid. I swam way too far out. My whole life, my family’s lives, we’re all so invested in this and have sacrificed so much and are depending on this. Why would I sacrifice that for a bunch of fuckups? No way.”

Indeed, one listen to the new Prequelle makes it clear that Forge will not sacrifice his vision for anything or anyone. Not only has he not lost a step, but he’s continuing to push out on the Ghost sound and story. To be sure, there’s still plenty of vintage-hued metal to be found on Prequelle, including the riffy, anthemic first single, “Rats,” and the stomping and shreddy “Faith,” but there’s also swelling, string-laden piano ballads (“Pro Memoria”), poppy, disco-metal confections (“Dance Macabre”) and a pair of incredibly catchy instrumentals, one of which, “Helvetesfönster,” features flute and nylon-string guitar (the latter played by Opeth’s Mikael Åkerfeldt ) and the other, “Miasma,” that builds to an explosive saxophone-solo climax.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

And Forge is only getting started. “The agenda has always been very rigorous and there’s always been a lot of ideas and concepts, and I still have not realized half of it,” he says. “I still have a lot to accomplish in the years coming. Believe me, there’s a lot in the pipeline going forward.”

The anonymity of the musicians in Ghost always seemed so important to the overall concept of the band. But now that the veil has been pierced, you seem almost reinvigorated.

Well, this is the thing—it was never like I was just waiting to be unmasked and then I was going to do this as per normal. Never. I don’t want to do Ghost as a normal, unmasked band standing around in, like, denim jackets. That was never the plan, regardless of whether people knew who I was or what size shoe I wear. So it doesn’t matter. For me, it’s the show that’s important. The make-believe part of it.

As far as the “make-believe” side of things, each Ghost album seems to revolve around a theme. When we spoke at the time of the release of Meliora, you said the album was about the “absence of god.” What is Prequelle about?

The return of god. And, for lack of a better way to put it, the day of doom, when god’s hand sort of reaches down upon the people. Like the Black Death. I wanted this album to have a sort of doomsday theme. But then it’s also themed around the idea of mortality and survival through turmoil, where you’re being judged and a doom has been cast upon you. How do you maneuver out of that?

When you’re composing songs, do the lyrics or the music come first?

The music comes first. Final lyrics are usually written very close to recording the vocals. It’s always been like a pulling-teeth situation for me, where some songs are definitely a knife to the throat on the day of singing. Like, “I need a lyric to this…now!”

Was there anything like that this time?

There are things like that every time. It’s endless. Because I always want to change things. But I usually come up with the important bits when I first begin writing. Like with the song “Rats,” I knew that was going to be the title and there was going to be the part that goes [sings riff] “Rrrats!” And from that it went through a lot of different shapes. But I very rarely start a song just with a riff. It’s usually a melody, and then it’s, “Here’s the verse, here’s the chorus.” And once I have that sort of transition, that’s when I have the song. Then I write riffs around that. That way there’s this steady melodic base. I might also write it with some bullshit vocals, and then I have to find my way with the lyrics around that. It’s varying degrees of pain.

You’ve hinted in the past that, even though you’re surrounded by Nameless Ghouls onstage, on the studio albums you play the majority of the instruments.

At some point or another I’ve played everything. But then to give you an example, you have heard the new album—I can’t play saxophone. But I can hum how I want a saxophone solo to be played. And I’m an able drummer, I can play Top 40 rock okay, but I can’t record hard-rock drums in a studio situation. That would be a waste of time. So I had a real drummer come in to do that work, even though I wrote the drum patterns. And that goes for all the records and all the songs. Even the songs that were co-written, I always played all the instruments at one point. So, when you hear Ghost, it’s my drum style. It’s my bass style. It’s my keyboard style. It’s my guitar style.

Are you playing all the guitars on Prequelle?

Yes. I performed all the guitars and all the bass. With one exception—in the song “Helvetesfönster,” there was a nylon-string part. I originally recorded it with electric guitar but it sounded weak. It didn’t sound cool. So I wanted it to be played with a nylon string. Now, I stopped playing nylon string when I was seven years old, so I called a friend of mine, Mikael Åkerfeldt from Opeth, who is very good at playing nylon string, to do it.

What was your guitar setup on the new album?

We did four rhythm tracks on everything. On one side we had a Les Paul gold top with P-90s that went through an Orange amp, and also a white [Gibson] Explorer from, like, ’82 or something like that—that typical James Hetfield sort of guitar—that went through an old Marshall rack amp from the early Nineties. And then on the other side it was a mid-Seventies Les Paul Black Beauty 20th Anniversary through one of those old Laneys that Tony Iommi used and an early Eighties [Gibson] Flying V that went through another Orange. Then I had a Seventies Strat for a lot of the leads, and I think I did overdubs mostly with the Explorer. So it was quite simple.

There are so many different styles that come through in your playing. Who were your influences as a guitarist?

There’s always a lot of classic rock—the old Sixties behemoths to, I guess, lesser-known stuff. And absolutely the heavy metal giants—Deep Purple, Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, Judas Priest, that sort of stuff—into the hard rock of the Eighties, the big arena rock. And then also underground death metal and black metal, and punk to a certain degree. I’m really trying my darndest to make this music as timeless as possible, even though it’s, to use an ambitious word, archaeologically going back to earlier music, especially Seventies hi-fi rock.

There is a definite vintage feel to Ghost’s music, but not to the point where it just sounds completely like a nostalgia trip.

Yes. I mean, it sounds different than your average sort of Black Sabbath rip-off sludge band. Because most of those bands that rave about Black Sabbath, the only songs they’re raving about and copying are the heavy songs. It’s never Black Sabbath’s more harmonic and grandiose tracks, like the ones you hear on Sabotage and Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, these albums that have ballads and really beautiful, humane thoughts. And that is the sort of Black Sabbath I am tapping into. That’s the sort of Black Sabbath I am inspired by. That sort of mid-Seventies period where they found orchestration.

In addition to the heavy stuff, you also have things like “Dance Macabre,” which has a dancey, pop element to it.

It does, yeah. I had the riff that starts the whole song, that was just a riff that got stuck in my head. I didn’t think of it as a Ghost thing at first. Because I heard the riff in a slightly more “synth-y” sort of way. But I showed it to some songwriting pals of mine and they were like, “That’s a Ghost song!” Oh, okay. I didn’t hear it that way at first. But it then it was, “Let’s make a Ghost song out of it…”

“Faith” has some great lead guitar playing in it. Clearly, you can shred if the part calls for it.

I can do it if I need to. But I guess that’s an ability thing. But one thing that sort of separates my way of learning to play guitar compared to a lot of others is that I sat with my guitar and my amplifier and I played a lot to records, but I usually came up with my own stuff over them. I never learned the actual solos. So in a cock-measuring contest where it’s about playing licks and playing fast techniques of others, I would definitely lose. Because I only know how to play my own shit. My ability maps my own writing. I haven’t spent a whole lot of time biting licks from the really quick masters. That’s why I’m not very good at that sort of super-fast, shreddy sweeping.

So I’ve never considered myself a traditionally good fast-playing guitarist. But I can do it, especially when I’m recording. With “Faith,” the solo called for an intense, aggressive part where I was like, “This needs to be aaargh!” I wanted to have that sort of attack you hear when you listen to something like [Metallica’s] “Hit the Lights,” where after every drum thing there’s this insane, quick, aggressive guitar bit. I wanted a piece like that but that sounded more evil. And I was able to do it.

In the past, did it ever bother you that because the band members were anonymous, you weren’t getting recognized for your writing or playing skills?

Yes and no. At the time I didn’t think of it as a negative. Because since I am the spokesperson for the band I’ve always been the one that had a full-time job with it. I was working all the time, writing, doing every sort of business thing you could imagine. It was very much a full-time occupation for me. Whereas it definitely wasn’t that for the others, who spent a lot of time just, you know, getting paid retainers. So I always felt from a positive point of view that I was given enough attention. I was given enough pats on the back to not bother with taking credit for everything.

However—when a lot of things were said and done and all of a sudden people were trying to rewrite the story of Ghost and sort of waving a flag for having done something they hadn’t done, that’s where I become a little like, “Wait, wait, wait—are you kidding? That was not your guitar. That was not your style. And if that was your style, write a record. Write a record that sounds like Ghost. You can’t.” That’s where I become a little childish. I didn’t bother to spell it out all these years, and I was fine with people basking in it or whatever. It’s fine. But don’t fucking lie about it. Don’t come out and, you know, aggressively claim that it was yours. That makes it a little bit difficult.

Have you ever had the desire to play the instruments onstage? Just grab a guitar and shred for the fans?

Well, over all these years when people have played it wrong, definitely I’ve wanted to be like, “Give me that god-dang…” [laughs] You know, there’s a lot of nuances in the recordings that I feel sometimes over the years have been missed. But, I mean, this is the thing. As I was saying, I am the director of the play. I just happen to play a part in it. But I’m also orchestrating it. So I don’t demand credit for every little smartass move everywhere, because I know where it all comes from.

As far as where it all comes from, what was your original intent with the sound of Ghost?

I wanted it to sound like the most gelled-together, intuitive band ever. And to sound like a band that plays just the right amount of stuff. Because whenever you have a band where you have phenomenal players, they usually overplay and they don’t really leave enough room for someone else. I mean, for a long time I always thought Frank Zappa had these amazing jam musicians. And then, haha, fuck me, little did I know that he wrote everything and that it was all totally scripted. But it sounded like it was, you know, this band just standing there, all flowing with it. So I guess that’s a little bit of my approach as well.

You want Ghost to be a band—even if, behind the scenes, you’re the one responsible for most everything that’s being put out there.

Yes. I’ll gladly give away the applause to someone else. That’s completely fine. I just want everybody onstage to have fun. And I want everybody in the crowd to have fun. And to believe.

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.