Pink Floyd legend David Gilmour takes us inside the guitar sale of the century

"There’s no statement of intention to retire," David Gilmour tells us. So why is he selling off some of his most iconic guitars?

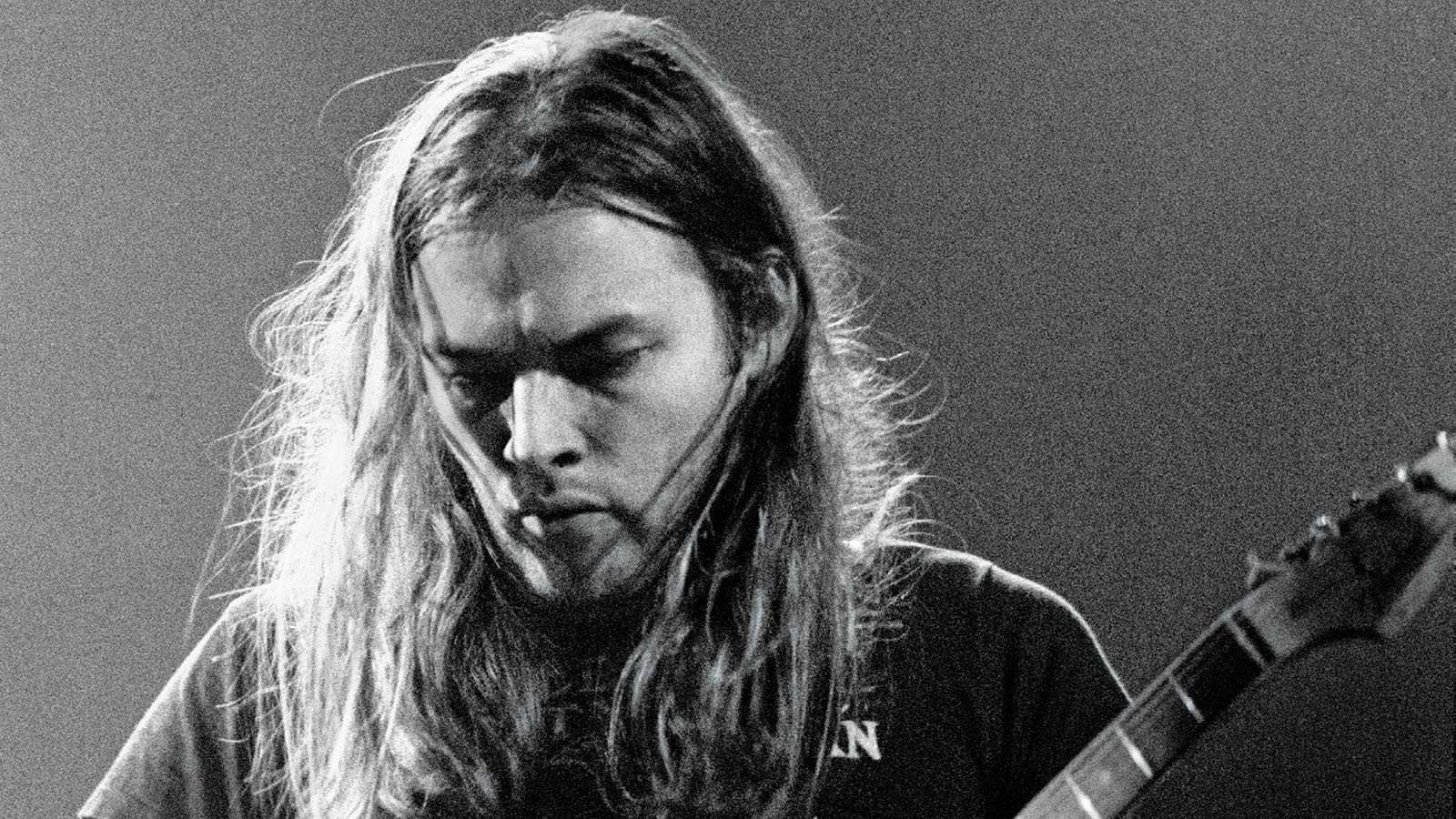

When Pink Floyd guitarist David Gilmour recently announced that he planned to auction his guitar collection, including the priceless instruments heard on such albums as The Dark Side of the Moon and The Wall, the six-string world gasped. Many chalked it up to a momentary lapse of reason, but he says the idea had been brewing for quite some time.

“It’s something I’ve thought about for years,” says Gilmour in his soft-spoken but deliberate way. “These guitars have served me very well. They’ve given me songs and tunes, but I thought it would be good for them to move on and create new music with different people. Hopefully, they’ll also raise a fair bit of money, which I plan donate to charity, and that will do some direct good in this world with all its difficulties.”

Not since Eric Clapton auctioned many of his instruments back in 2004 at the James Christie salesroom at Rockefeller Center in New York has an event caused such anticipation in the guitar community. Set for June 20 at Christie’s in Manhattan, Gilmour’s 120-plus guitars are expected to reap millions.

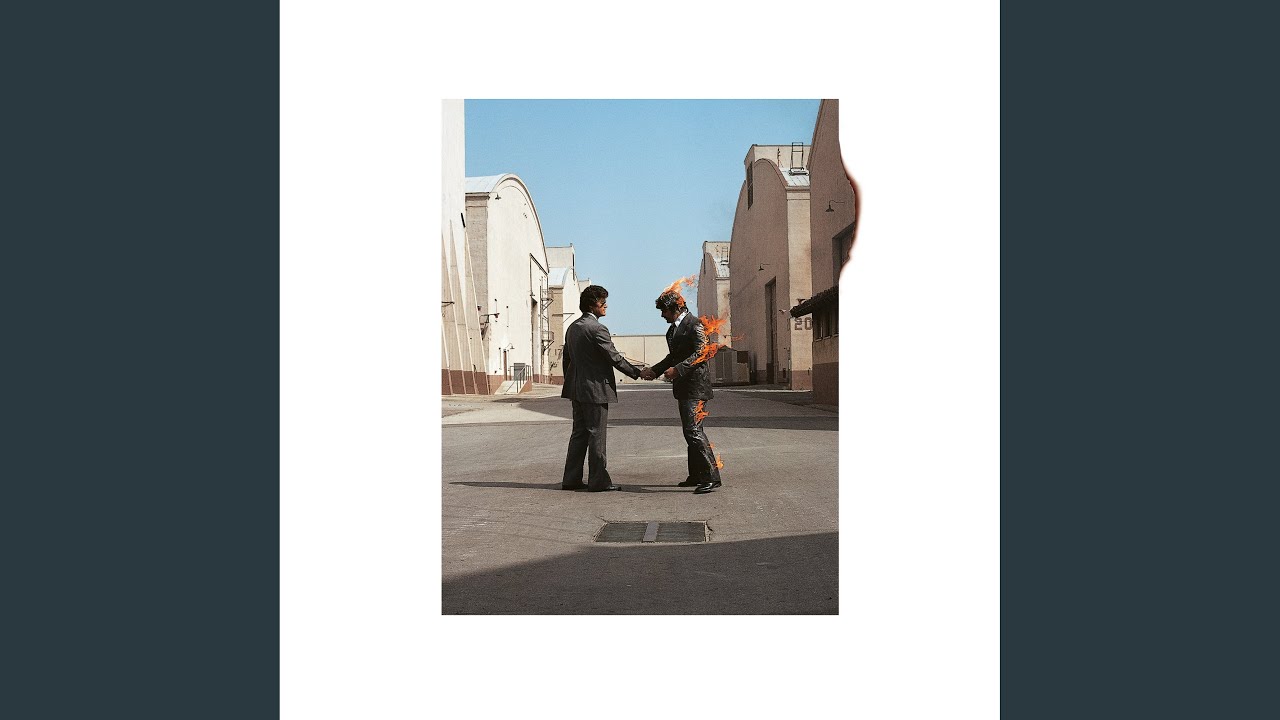

Among the most sought-after instruments will be his extremely rare #0001 Fender Stratocaster, used on Paul McCartney and Wings’ 1979 album, Back to the Egg; a Candy Apple Red 1983 ’62 Reissue Strat that served as his main performance guitar for more than two decades; and the 12-string Martin acoustic heard on Pink Floyd’s “Wish You Were Here.”

But the star of the auction will no doubt be Gilmour’s famed ’69 guitar, known as “the Black Strat.” Used on some of the world’s biggest-selling albums, and featured on Pink Floyd classics like “Money,” “Comfortably Numb” and “Shine on You Crazy Diamond,” the instrument exists in a galaxy of its own. Like Jimmy Page’s EDS-1275 double-neck or Stevie Ray Vaughan’s #1, the Black Strat is one of the most famous and coveted instruments of the last 100 years.

Gilmour admits it will be tough to let these iconic instruments go, but he’s 100 percent certain it’s the right thing to do — and the right time to do it.

The first question is… how could you?!?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

[laughs] The big picture is I want to raise some money. There are a lot of major problems in our world today in terms of refugees and starvation. I have a charitable foundation and the money will be distributed from there to the people that need it most throughout the world. It will be just a drop in the bucket, but many will potentially benefit from this sale. That’s more important to me these days.

Do you have any sentimental attachment to your instruments, or have you always thought of them more as tools of the trade?

That’s a difficult one. I had my teenage dreams of having a Fender Stratocaster, and then I bought one and it was great. I still romanticize Stratocasters and some of these guitars to some extent, but the more rational me does think of them as “tools of the trade.” While my Black Strat is special, I don’t feel I won’t be able to achieve just as much on a different guitar. So, yeah, I guess I’m not overly sentimental. [laughs]

I can understand that. Your Black Strat has been so heavily modified, in some ways, it’s not even the Strat you bought in 1970.

That’s right. The neck has changed two or three times, and I think maybe more than one pickup has been changed on it. There have been several modifications done to it, most of which have been undone again at some point. But that’s part of the reason it’s my special guitar. I worked out all my crazy ideas on it. I did add a little switch that allows you to select just the bridge and neck pickup, which isn’t possible on a normal Strat. It was an idea. I haven’t removed that idea, but I rarely used it.

In recent years, you were playing the Black Strat with a strap that used to belong to Jimi Hendrix. Will that be part of the deal?

No! [laughs] No, I’m hanging on to that, I’m afraid. My wife gave that to me as a birthday present a few years ago, and it’s staying with me.

Of the 120 guitars that are being auctioned, which are the most valuable to you?

Well, obviously, the Black Strat. It has served me extraordinarily well. It’s on all the Pink Floyd records from the Seventies. The opening notes of “Shine on You Crazy Diamond” fell out of that guitar one day in 1974, and the solo on “Comfortably Numb” was done on that guitar. It’s really on everything during the Seventies.

My 1969 Martin D-35 is something I’ll miss. I used it for the lead parts on “Wish You Were Here,” and it was my main acoustic guitar through the Seventies. I still use it all the time. It’s the nicest guitar I have for just plain, straight strumming. I’m also auctioning my Martin D12-28, which is the 12-string I wrote “Wish You Were Here” on.

And then there’s my Ovation 1619-4 six-string acoustic that was very useful to me for a long time because of its internal electronics. It’s also important because that’s the guitar I restrung using some of the high strings from a 12-string set, which inspired me to write “Comfortably Numb.” I used it for almost every live performance of “Comfortably Numb” through the years.

What will you use moving forward?

I’ll hunt something down that I’m sure will do the job just as well.

There are so many more options these days. It was often difficult to find great guitars in the Seventies.

Yeah, I guess so. But I do unrepentantly like the old ones. Older instruments have a tonality of their own that often takes years to develop.

But you’re right, these things go in waves. Acoustic guitar makers like Gibson and Martin went through periods where they were manufacturing beautiful guitars, and then they went through periods where they tightened their overheads and made things that weren’t so good. Eventually they learned their lesson, and in the long run they went back to making great guitars again.

Luckily, I know the periods of guitar, and the types of guitar that I like, and I guess I’ll eventually hunt down another 1969 D-35 that is as good as the one I originally owned. You just need to look in the right places, and as you say, there are a lot of them about these days.

I was wondering about the blonde Tele that your parents gave you for your 21st birthday.

It was actually a white Tele. Unfortunately, that is long gone. I shipped that one to America in the late Sixties, and TWA lost it. I’ve never seen or heard of that one again, which is a shame. It was my first Fender.

Will you be parting with any of your lap steels?

Some of them. The Jedsons and Fenders are going. I’ve got a few Rickenbackers, but I might hang on to one of those.

Do mind if I ask what you are planning to hang on to? It doesn’t sound like much.

There are a few things. I’m keeping a lovely old Gibson steel guitar that has a really beefy sound. I’m holding onto a black Gretsch Duo Jet that I really love, along with a 1945 Martin D-18. I also couldn’t bear to part with my ’55 Fender Esquire that I nicknamed “The Workmate.” It’s the one you see on the cover of my About Face album, and it was used on “Run Like Hell” from The Wall, among other things.

Are there any surprises in the collection, or maybe some hidden gems people would not be familiar with?

I don’t know that there are, really. But there’s all sorts of interesting instruments in the collection — things that came into my possession one way or another. The Melobar guitar is quite cool! It’s sort of a combination of a steel guitar and a standard guitar. The neck is at a 45-degree angle so you put a strap on it and play lap steel while standing up. It’s a good idea, but I never used it that much. There’s also a Django Reinhardt-style plastic Maccaferri somewhere.

Does the auction signal your retirement in any way?

Not really. I still write stuff all the time, and there’s no statement of intention to retire. I’m just unburdening myself of a huge collection that at some point will have to go. This just felt like a good moment to raise some good, hard cash for people who need it.

There are a lot of beautiful old guitars in the world, and I can track down some replacements if I need to. And if I really feel desperate for something I’ve auctioned, I can find the person I sold it to and make them an offer they can’t refuse! [laughs] Inevitably, I’ll buy more guitars; I just don’t want to have a stock that I keep in a cupboard or in their cases for too long.

Can you relate to why people might want to buy these guitars? I mean, would you get a thrill out of playing, say, the guitar Albert King used on “Crosscut Saw”?

Hmmm, I’m not sure. I can’t really remember having the desire to play somebody’s guitar. Perhaps it’s because I’m so wedded to the idea that my sounds come more from my fingers than from the guitar. I guess I would be happy to play a Hank Williams guitar or something like that, but I’m just not overly sentimental about the guitars and their history. As I said earlier, I’m more a “tools of the trade” sort of guy.

In addition to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, other major museums are mounting exhibitions devoted to rock and roll and music of the 20th century. Do you think that’s valid?

An instrument is an accessible token of where the music came from. Obviously, they can’t stick the person in the museum and be like, “Laaa.” I’m kind of okay with it. I know that people go to museums and look at instruments and feel a kind of kinship with the music they’ve grown up with. I don’t have anything against it, but I think instruments are meant to be played.

It’s interesting. I have no control over who is going to buy these guitars, but hopefully some real musicians will get some of them and they will go on to create some new music and get real joy out of them. But one has to face the reality that some of these will go to people who just want to put them up on a wall or behind glass. Who knows? But maybe, in the long term, they’ll get out there and do something again.

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away Brad was the editor of Guitar World from 1990 to 2015. Since his departure he has authored Eruption: Conversations with Eddie Van Halen, Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page and Play it Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound & Revolution of the Electric Guitar, which was the inspiration for the Play It Loud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 2019.

“It holds its own purely as a playable guitar. It’s really cool for the traveling musician – you can bring it on a flight and it fits beneath the seat”: Why Steve Stevens put his name to a foldable guitar

“Finely tuned instruments with effortless playability and one of the best vibratos there is”: PRS Standard 24 Satin and S2 Standard 24 Satin review