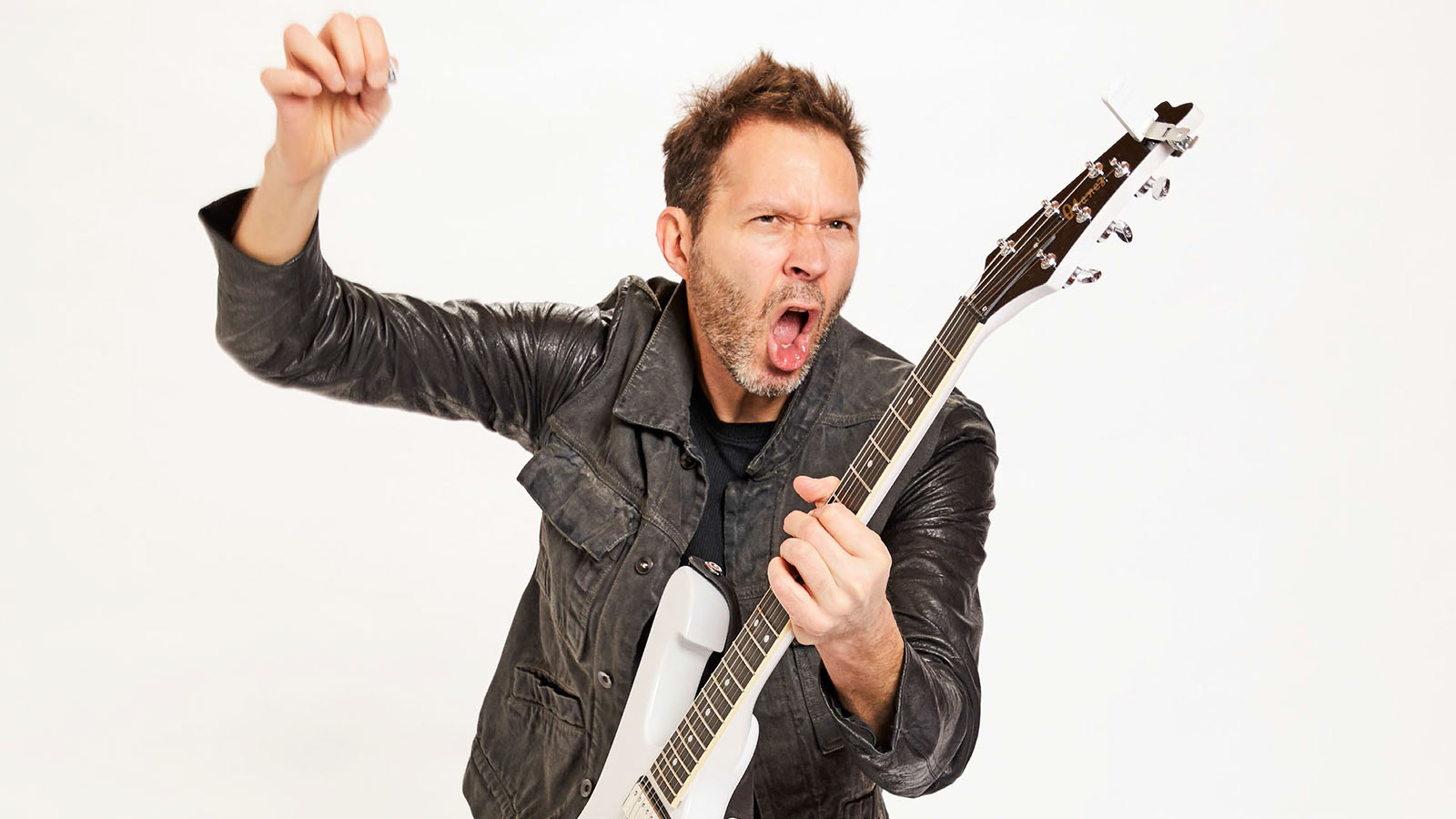

Paul Gilbert is a really big Beatles fan. At various times over the past decade, he and ex-Dream Theater drummer Mike Portnoy satiated their Fab Four Jones by playing in a tribute band called Yellow Matter Custard. The Beatles seem to always be on Gilbert’s mind in one way or another, and he references them frequently during our discussion, regardless of the topic at hand.

“It’s just kind of the way I think,” he says. “My brain has been programmed to listen to music a certain way because of the Beatles.” Even before he picked up the guitar, as a child growing up in in the Pittsburgh suburb of Greensburg, Pennsylvania, Gilbert listened to the Beatles nonstop, and he recalls the devastation he felt when he heard they were breaking up. “I was shocked,” he says. “I was only three years old, but something about their writing was so gripping to me that I couldn’t imagine a world without them.”

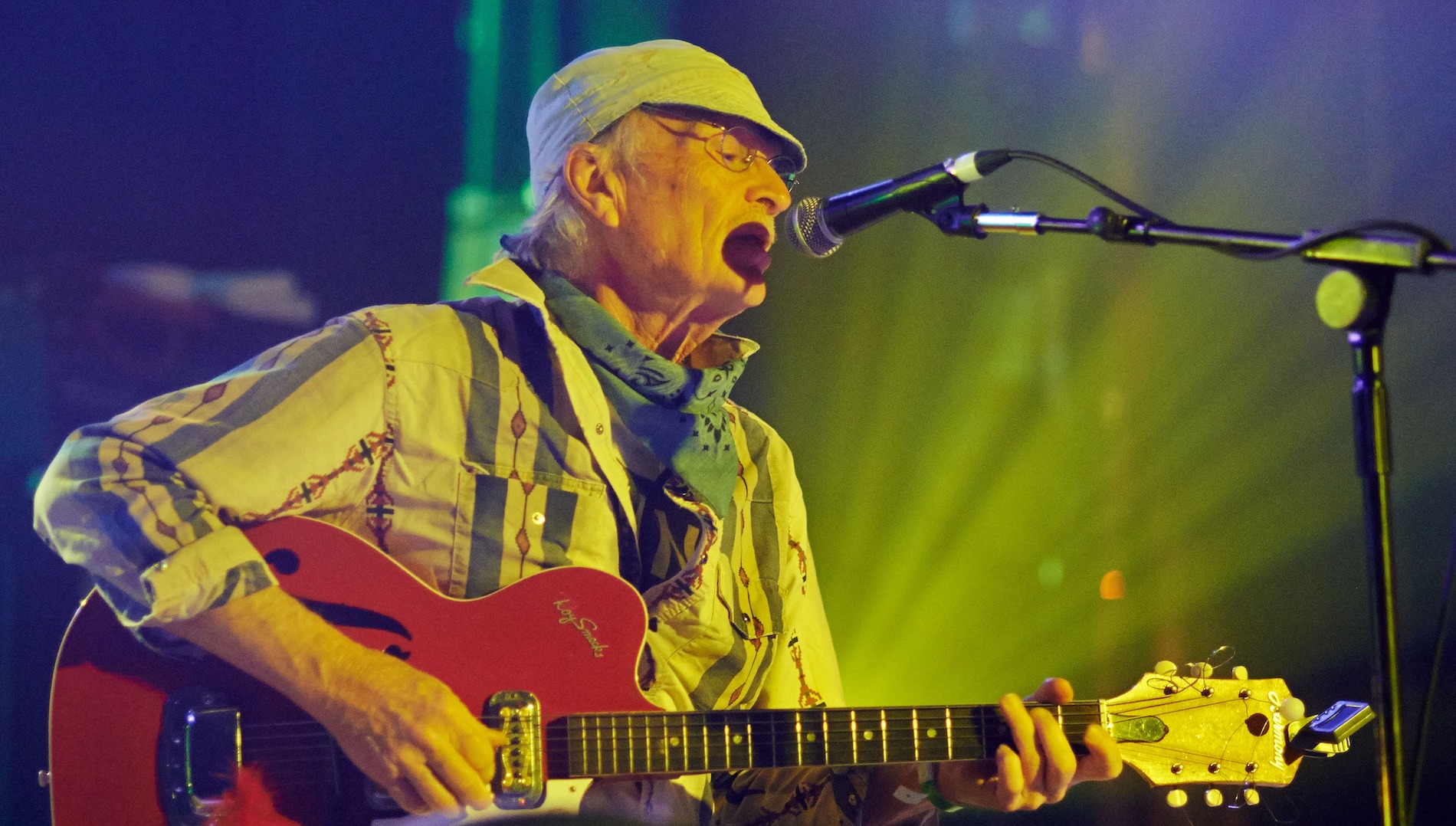

Although he never ditched his Beatles records, Gilbert eventually found new heroes — six-string monsters like Eddie Van Halen, Jimmy Page, Robin Trower, Pat Travers and Tony Iommi, among others — and after only a few years of emulating their licks, his preternatural skills on the guitar brought him to Los Angeles, where he was quickly hailed a teenage wunderkind. By day he would teach the hottest techniques to poodle-haired axe hopefuls at the Guitar Institute of Technology (GIT), and by night he performed — sometimes wielding an electric drill — with the late-Eighties high-speed shred band Racer X. “I went from wanting to be a Beatle to becoming a ‘widdly-widdly’ guitar player,” he jokes.

With his Nineties supergroup Mr. Big, Gilbert attempted to forge an accord between the two warring factions of his musical brain. While he and bass virtuoso Billy Sheehan never missed an opportunity to hotdog it on jaw-dropping unison runs, Gilbert paid homage to the Beatles by writing hook-filled, psychedelic gems like “Green-Tinted Sixties Mind” and “Mr. Gone.” The band even scored a number one smash with the Beatles-y, acoustic sing-along ballad “To Be with You,” on which Gilbert’s vocal harmonies echoed both John Lennon and Paul McCartney while his sweet guitar soloing recalled George Harrison’s deceptively simple lead style.

Throughout his solo career (which he began after leaving Mr. Big in 1999 and has maintained even after rejoining the group in 2009), Gilbert continued to push the boundaries of synapse-altering guitar daring-do while staying true to Beatles roots; his records often alternate between dizzying instrumentals and Sixties-tinged, pop-flavored vocal tunes. Both sensibilities co-exist beautifully — in fact, at times they seem to merge as one — on his latest album, Behold Electric Guitar, but he even adds some new colors. Many of his riffs and solos feature stinging, bluesy slide work, and a great deal of his licks are informed by his new-found affinity for jazz.

“Listening to jazz over the last few years has really opened my ears to how a melody can be handled by an instrumentalist but still have the authority to be gripping to the listener,” Gilbert observes. “I didn’t hear much jazz as a kid, so it took me a long time to come around to it. It sort of snuck in through the blues door.”

Behold Electric Guitar is full of other firsts for Gilbert. It’s his debut album for the online direct-to-fan music platform Pledge-Music, and it marks his first time working with Joe Satriani’s longtime producer/engineer, John Cuniberti. Originally, the two attempted a “crazy concept” of recording the whole band (Gilbert, bassist Roland Guerin, keyboard player Asher Fulero and a rotating cast of drummers) with one microphone, capturing every performance as a listener might hear it, but in the end they opted for individual mics on all the players.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Even so, the album is comprised of all-live takes with no overdubs, and in this way it can be viewed as Gilbert’s Let It Be — a spontaneous “warts and all” document.

“It was a very demanding project because we really had to play well,” he says, “but that’s exactly what I wanted ‘demanding’ to be. I much preferred it to, ‘Whew… We just spent 10 hours editing and mixing.’ I’m in a place right now where doing lots of post-production work just seems like a waste of time. Playing live music and having it finished and sounding great right away makes me feel truly alive. I absolutely get high from it. That’s what music is about.”

Compositionally, what was your overarching agenda for your new record, Behold Electric Guitar?

My initial ideas are just a starting place. As a record goes along, it becomes more about making discoveries and getting excited about new songs. I guess the main discovery I made this time was how well it worked to write melodies from a vocal perspective — even writing pages of lyrics — and then to use those vocal ideas as a framework for guitar to take over and play the melody instead.

It took me a long time to accept the idea that the guitar can take the place of a singer. Since I grew up listening to the Beatles, I always thought that singers should handle the melody, and that the guitar should play chords, riffs or bluesy solos. Blues is like the “gateway drug” that lead to digging jazz. I really enjoy jazz now, which is totally surprising to me. Letting jazz elements into my playing scares me a little, because I still respect my 16-year-old self as well as all the kids out there who want to rock. At the same time, if I love something, I have to love it. And it’s really exciting to me to have opened doors into these new worlds and to be moved by what I find.

What brought about the move to Pledge-Music? And how is doing an album for them different than working with a traditional label?

My friend [singer-songwriter] Linus of Hollywood was doing an album for PledgeMusic, and I asked him how it was going. He was really happy with how it was working for him, so I went to the site, and I saw artists like Joe Satriani, Bon Jovi, Black Sabbath and Judas Priest with various products on there. I felt like I was late to the party, so I talked to my manager, and we decided to try it.

The biggest surprise to me is how much I enjoyed getting feedback from listeners during the making of the album. In the past, I’ve always wanted to keep the music top secret until the record was finished. But that can sometimes be a nerve-wracking process, because without any feedback, you don’t get a sense if anyone will actually like what you’re doing. Self-doubt creeps in and makes you second-guess yourself and you become a bit paranoid and crazy. But from sharing small pieces of the songs on my PledgeMusic video updates along the way, I got lots of encouragement from people, and that really made a difference to my level of sanity as I wrote the album.

Was John Cuniberti’s history with Joe Satriani a big factor in working with him? And what made you guys try to record to one mic?

I actually heard about John through his “OneMic” project; I was pleasantly surprised to find out that he had worked with Joe Satriani. John had been doing lots of sessions at the Hallowed Halls studio in Portland, where I now live. I was researching the studio, so I checked out videos that John had engineered, and I thought they sounded great. The idea of recording with one microphone really appealed to me. The OneMic sessions tended to be quieter acoustic bands with vocals, so I was a little concerned that loud instrumental guitar music might not be what he was used to. We did a test session to see how it would go, and it turned out great.

I was really excited to try that approach for the album — one stereo mic pointed right at us — but when John heard us play while tracking he thought that we sounded better by miking the instruments separately. We still set up close to each other and played live with no overdubs. I hope to record with one mic in the future, but I may need to play a little quieter so I’m not overwhelming the band.

You tried so many daring things on the record. And you used a band you had never worked with before, either.

That’s right. Since I moved to Portland, I wanted to meet some local musicians and see what kind of players were there. I had already done some work in a couple of area studios, so I asked the engineers for recommendations, and that’s how I heard about Brian Foxworth and Asher Fulero. Brian’s groove is just ridiculously solid, and he knows the names of about 27 different kinds of shuffles. And, of course, he can stir up some ferocious fills if a song starts heating up.

I originally wanted Brian to play drums on the whole record, but after my sessions he’d play other gigs at night. He got so exhausted that one day we had to call paramedics to take him to the hospital! The studio owner knew a great drummer named Reinhardt Melz, and he was able to come and keep our sessions rocking for a couple of days. But I also had live shows coming up, and Reinhardt wasn’t available for those. So I called Bill Ray, a great drummer from Seattle whom I had recorded with before. Bill came down and did an amazing job finishing the sessions with us, and of course, that gave him a great start for playing the new songs at my live gigs.

Asher plays a really wide variety of music, and after I hung out with him for just an hour, he had already expanded my horizons. I could also tell that his influences were not just keyboard players; he was really looking outside of his own instrument for inspiration. It’s nice to have a fellow seeker aboard.

As for Roland Guerin, I had recently jammed with him at an Ibanez event at Sweetwater Sound, and we got along really well. He’s from New Orleans, and he plays bass with all the legendary blues cats there. He also plays upright bass really well, both with fingers and a bow. I asked Roland to come out to Portland early so we could rehearse and prepare for the sessions, and fortunately he had time.

In your making-of video for “Love Is the Saddest Thing,” you talked about how you “cheered up” your mournful lyrics by turning the song into a fast rock shuffle.

I love writing music from lyrics — it’s like solving a rhythmic and melodic puzzle. So I just take the words and try everything I can think of. The fast shuffle version just had the best energy when I tried it, and I liked the contrast of the “down” lyrics to the “up” music. That’s one of the things I love about the blues. It seems to ease life’s problems with a sense of humor. [Sings] “My baby don’t love me no more, but I still got my guitar, and… maybe her sister will!”

I understand there’s quite a story to the writing of “I Can’t Listen to Music Where Every Snare Drum is the Same.”

I was listening to some Elvis Costello when I got the idea for that song. I can’t remember which album it was on, but Elvis was playing something in a 6/8 groove, like the Beatles’ “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away.” The lyric idea was rattling around in my head from a recent trip to Hawaii where the music in every restaurant was bothering me. It was some kind of modern background music, and it would repeat the same phrase over and over, and the snare drum became like Chinese water torture. In a traditional music composition, from classical to pop, there is a common structure in which a phrase is played, then repeated — often with a slight twist — and then it takes off from there. But the restaurant music was like an endless, repeated phrase. I found myself unable to ignore it.

Asher had a great theory for this. He told me, “You’re looking for creativity in the wrong place.” His theory was that a lot of modern styles are not about melody, chords and traditional arrangement. The creativity is in texture. The sounds themselves are interesting from a purely sonic perspective. This is doubly challenging for me, because it requires me to stop looking where my instincts tell me to look.

Also, because I have severe hearing loss, texture is difficult for me to actually perceive. But it’s comforting to know there is still creativity there. It’s just hidden around a corner, where I can’t get to it. But at least other people in the restaurant could. I was looking around thinking, “Why isn’t there a riot? Doesn’t this annoy everyone else?” Anyway, I’m over 50 now, so maybe I’m just an old man ranting.

You started writing “I Own a Building” as a vocal song, but you turned it into an instrumental. Why was that?

The truth is, I’m coming to terms with the limitations of my voice, but I’m still trying to express the melody with my guitar. When I sing, there is an almost constant struggle with pitch and with reaching notes in the higher register. On guitar, high notes aren’t a problem at all. They’re there for me whenever I need them, and that’s kind of wonderful.

Your bluesy slide playing on that song is quite striking.

When I was working on my last record, [2015’s] I Can Destroy, I discovered I play slide much better when I use my middle finger. Because I’ve been listening to so much blues, I think my ear was also primed for slide. Recently, I had some powerful magnets glued into the lower horn of a few of my guitars. This holds a metal slide in place so I can easily get to it and put it back, even in the middle of a song. So I’ve been able to spend a lot more time with the slide since it’s always within reach. The challenge is that I’m always playing slide with standard tuning and light strings. I keep my action on the high side, which is not only good for slide, but it’s also good for vibrato and bending when I’m playing normal guitar without the slide.

“Sir, You’ve Got to Calm Down” starts out with a fiery riff, but then eases into a funky groove. Are some of the chords the result of your listening to jazz?

The main “unusual” chord is an Eadd9 with the third in the bass. The guitar voicing looks like a Bsus/G#, but it functions more like an Eadd9/G#. It’s a very move-able shape, so it can get me out of a tangle if I’ve modulated somewhere and can’t find my way back. I think I might have learned it from Pat Travers, Chaka Khan or Steely Dan. Or maybe all of them!

How married to your demos were you in terms of solos? Did you change them up once you actually cut the album?

I rarely make demos anymore — I’m too busy! And I’d just rather trust the band to do what they do. I used to put so much time into demos, and it felt like I was making the record twice. Now I’m a dad and a husband, a teacher at my online school, and I’m the guitar player for Mr. Big, so when I do my solo music, I can’t spend months messing around. I’ve got to get things done quickly and efficiently. For the most part, I think that improves the result.

In the videos you posted, you’re playing various Ibanez Fireman guitars. Were those your main axes for the album?

I’ve become quite fond of my guitars that have the slide magnet on them. I’ve got a white FRM200, a red FRM150 modified with three DiMarzio PG-13 mini-humbuckers and a white PGMM31 miKro, all modified with the slide magnet. Those are the guitars I brought to the studio. I’ve also got a purple custom shop Fireman with a locking tremolo on it. That guitar looks so cool, so I brought it just in case. All are Ibanez, of course. I’ve been with them over 30 years now, and I couldn’t be happier.

Your amps were Marshalls, right?

I used a Marshall Bluesbreaker combo for the whole album. I put it right in front of me, so I could really feel the punch and percussion when I picked a note. It’s so much better doing it that way than having the amp isolated in some other room.

Are there any new effects you’re using?

My main pedals, in order, were a Fulltone Deja Vibe — the old one in the big box — an Xotic Effects AC Booster, a Supro Drive and a TC Electronic MojoMojo. I ended up not using reverb or delay in the studio because John Cuniberti wanted to control them on his end.

Along with Behold Electric Guitar, you’re also releasing Vernon Solos — you back in 1988, playing for an hour straight.

That’s right. Racer X used to rent a rehearsal room at an old building in Vernon, California. It was great because we could leave our gear set up and go in and play at any time of day or night. Playing through a cranked-up, fire-breathing Marshall is a lot different than playing at a polite level in an apartment. So I used to show up to rehearsal early to build my instincts on how to control feedback and string noise — and just experience the mild terror you get from being loud. I set up a recorder, plugged in a couple mics and recorded all the scary stuff I was working on at the time. I’m different now than I was then, but I like that kid a lot.

How much tweaking did you have to do to make an old cassette sonically palatable?

I had heard that old cassette tape can just fall apart, so I was a little nervous when I put this 30-year-old tape in the machine. But it sounded fine, and the guitar playing was even more face melting than I remembered. I sent the audio file to my mastering engineer, Paul Logus, who put a lot more care into his work than I was expecting. It sounded “good enough” from the cassette, but Paul really worked some magic with his gear and ears. I’m excited for people to hear me tearing up the guitar in 1988!

The Beatles continue to be an inspiration to you. Before our interview, you said you read a book on them that you liked a lot.

I did. The book is called The Songwriting Secrets of the Beatles by Dominic Pedler, and it’s awesome. Being a Beatles fan has influenced my instincts and my intellect. From going to Musicians Institute and from reading Dominic’s book, I have an intellectual sense of the Beatles’ habits and tricks. But most important are the instincts I have from just listening to the songs and playing them a lot.

I should mention that I also play their songs on piano all the time. I’m not a great technician on piano at all, but it’s such a great instrument for listening to chords, and it’s fun to bang out my favorite songs from my guitar memory and translate them to piano.

You moved from Pennsylvania to L.A. as a teenager. What are your memories of the hair/shred metal shred scene back then? Did you fit in? Did you feel like an outlier?

I think normal attracts normal. I read an unauthorized biography on Yngwie Malmsteen a while back, and he came to L.A. around the same time I did. But his experiences were so different than mine. I never really saw drugs, alcohol or destructive wildness. I went to music school, practiced a lot, researched and listened to a lot of new music, and I made friends with other musicians.

The big difference from Pennsylvania was that the musicians in L.A. were much more driven to have a career. They didn’t see it as a hobby. They were in it for life. And because of that, they would show up to rehearsals and deliver the goods when they played their instruments. I played with some really talented people in my teenage bands in Pennsylvania, but it was hard to get them to commit to music 100 percent. Maybe it was easier for me because I was young and I never had a job that paid anything.

Finally, is there anything on the guitar you’d still like to do that you can’t?

Melodies are still a huge challenge. If I pick up a kazoo, I can play a melody without having to think about it. To play a melody on the guitar, I really have to pay attention. But if I have a chance to practice a bit, I can get more expression and tone from the guitar than from the kazoo. And this is such a new road for me to travel; I feel that it’s only going to get easier. And when things get easier, you don’t have to think about them as much. And that’s when I can go onstage and only think about one concept to get me through the whole night: connect. Connect to the band. Connect to the audience. Connect to the universe, if it happens to peek its head into the gig. And that feels so good.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.