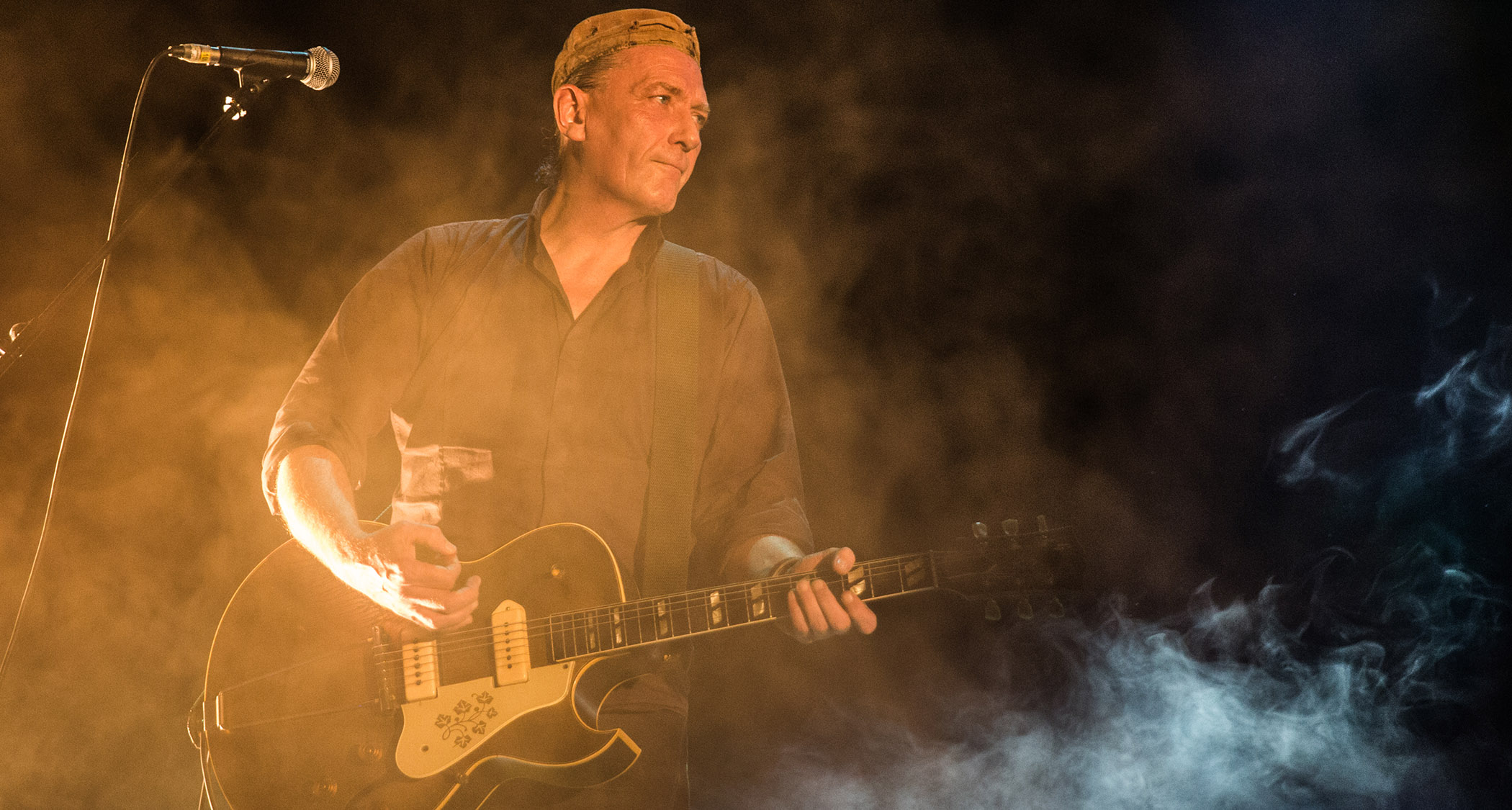

Krist Novoselic on his favorite basses, Nirvana's legacy and Giants in the Trees

Krist Novoselic dishes on Giants In The Trees, and talks about playing in one of the biggest bands of all time

In the gamut of “Where were you when …” musical moments in history, the release of Nirvana’s groundbreaking 1991 hit “Smells Like Teen Spirit” is undoubtedly high on the list, somewhere around Jimi Hendrix’s Woodstock performance.

The song became the anthem of a new era, capsizing the hair-metal frenzy of the ’80s and sparking a musical genre—and more to follow—while skyrocketing a modest Seattle trio to becoming the biggest band in the world.

The album Nevermind went on to sell over 30 million copies and, as you likely know, ultimately led to the demise of singer Kurt Cobain, who took his own life in ’94. You probably also know that Nirvana drummer Dave Grohl went on to form Foo Fighters, which became another rock juggernaut.

That leaves Krist Novoselic. Known for his big stage presence (and not just because of his 6'7" stature), his ability to write rhythmically melodious riffs, and for possessing some of the most distinguishable tones in rock, Novoselic made a massive mark on the bass with Nirvana; listen to his work on “Lithium,” “In Bloom,” “Breed,” and “Dumb” if you need a refresher.

After the disbanding of Nirvana in 1994, Novoselic moved on to a slew of projects and interests, including directing and appearing in films, writing columns, flying Cessna aircraft, speaking out about politics and rallying for social activism, and of course, continuing to play music.

He contributed his playing to Flipper, Mike Watt, Johnny Cash, the Melvins, Sweet 75, Eyes Adrift, Foo Fighters, and eventually even Paul McCartney. But after he influenced so many musicians, fans of the 52-year-old bass icon have been waiting for him to release his own music. An impromptu jam session at a small-town music hall in the Pacific Northwest finally turned that into a reality in 2017.

For the past 25 years, Novoselic has been living in southwest Washington’s Wahkiakum County, a place with around 4,000 residents, about which he cheerfully remarks, “We’ve got the internet.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

That’s where Novoselic responded to a flyer for an open jam, in which he grabbed his bass and trusty accordion and met Jillian Raye (banjo, bass, vocals), Erik Friend (drums), and Ray Prestegard (guitar, harmonica).

After playing through a few progressions, Novoselic tossed out some riffs that quickly became a song they’d later name “Sasquatch.” By the end of the session, they had multiple songs outlined and a new band they’d eventually name Giants In The Trees.

Novoselic and company couldn’t care less about chasing the wildfire success that Nirvana experienced, as their focus is on songwriting. Tracks like “Seed Song,” “System Slave,” and “Sasquatch” have folky, Americana shades to their alternative indie core, but the bass work unmistakably echoes the Novoselic lines that we grew up revering.

With Raye taking over bass duties during the live shows when Krist draws his accordion, the low end is always in the forefront of Giants In The Trees. It’s an appropriate band name for a rock star who has been living in the remote woods of Washington since the height of his fame. Finally, this giant is re-emerging from the forest.

How different is it forming a band now, compared to when you started Nirvana?

Everything has changed so much since 1992. I’ve been told that Nirvana was the last pre-internet band, before everything went online. The music industry is a different thing now; it’s been in disarray, but now it’s starting to get its footing again.

You can get your music out there, but there are different modes to do so now. The old paradigm was to get on a label and get on MTV and on the radio to have any shot of being heard.

And the labels would push you. Remember when labels would shelve bands? Remember how many careers they destroyed just because they decided to? It would render a group powerless when they’d do that.

Well, now it’s flipped over, and now you want to pull people. It’s why you have exploitation and fake news on the internet, because you want to pull eyeballs in instead of pushing [content]. Luckily, I have a profile in the music industry, which helps this band tremendously. It helps me get that music out there and pull people.

Does it feel like every project you take on has to compete with Nirvana’s success?

Yeah, there’s that, but when you start a new band it’s like you have to start from scratch again. You have to go back to playing small clubs and getting your music out, and then you move up a notch and get into playing festivals.

That pressure might be there, but you just have to focus your energy on your new band. In the end it’s almost the same when you’re performing, if you can connect with the audience and feel that reciprocal energy.

It’s the crowd feeding off the band and the band feeding off the crowd. That’s when the magic happens. That’s the biggest reward, and while it’s hard to put a finger on it, you can feel it. That’s what I focus on. Not past experiences.

How did Giants first form?

We started in summer 2017 when we jammed at an open call for musicians, and the core players of this band showed up. I was playing an acoustic bass guitar—an Epiphone that I had gotten for free because I played a show with Dave Grohl, Pat Smear, and Beck in Beverly Hills.

Our manager got an acoustic to replicate the one I had in [Nirvana’s] MTV Unplugged episode. Anyway, I busted out some riffs, and they all jumped in, and it turned into the song “Sasquatch.” We wasted no time getting into it. Then I had some riffs on accordion, and that turned into a song called “Center of the Earth.”

It all clicked really well, and one thing led to another, and we decided to keep playing together. The forming was totally natural. We’ve worked together so well since we first met.

How did the rest of the material come about?

We would just jam, and then the bass line would come out, and then the vocal part and then the guitar part. We’d work it all together from there. Some songs were written before by Erik or Jillian or Ray, because I was looking at their past work to see if anything spoke to what we were trying to do. I’d bust out bass riffs a lot of the time and we’d just run with it, and then it came together and we’d have a song.

How did you track your bass for the album?

I went straight mics for this. On In Utero [1991] I didn’t use a DI, but I did on Nevermind. At the beginning of this process I used some Hiwatt heads that I had used on In Utero and on a lot of Nirvana gigs, but they started breaking down on me, so I donated them to the MOPA Museum in Seattle that has a Nirvana exhibit.

From there I used a big Ampeg SVT through the same 8x10s I’ve used forever. We set it all up in a bedroom and put mics on them, and I’d use a little rack distortion for some growl. Then I played my old Gibson RD bass from the ’70s.

I pulled that out from my closet when [Gibson] wanted to make my signature bass—it had broken tuners and electronics that didn’t work, so they refurbished it and now it’s perfect.

You’ve always seemed to favor interesting and unconventional basses, like the Gibson RD and the Ibanez Black Eagle.

It just kind of happens. With the Black Eagle, I got that in Olympia [Washington] because I needed a bass on the fly heading out on a tour, and it was so cheap. Back then was great, because we had all this ’70s gear that was cool and solid and super cheap, and it was built really well.

We’d use it and beat the hell out of it and it would keep playing. I played the first Black Eagle on Bleach [1989]—I would seriously smash it every night, and it still sounded so good. If you want to get that Bleach sound, like on the song “Blue,” you just need a Black Eagle tuned to D and that’s that sound. I just did that the other day and it sounded exactly the same.

Can you see where the material is leading for the next Giants album?

We’ve already started working on it. In the old days, bands used to make two records a year, and that’s what we want to do. We’re feeling pretty prolific. We don’t have many shows lined up at the moment, so we have some time. We want to just go for it and stay productive. The new record is more pop-groove, kind of fun music with a down-home edge.

Is writing easier now that you’ve been playing together longer?

We know what we do now, so that helps us do it better. And a lot of that comes from knowing how each other plays now. We go for a lot of melody, and we’re not afraid to have big choruses. It all has more of an identity now.

What’s it like going to play a show with this band, knowing that a lot of people are there just to see you?

I feel grateful that people give us a chance, because that’s asking a lot of the audience. I don’t go see bands a lot, for a lot of reasons, but when I do I just want to see my favorite songs.

When you’re asking your audience to come listen to a band’s material that they’ve never heard before, you’re asking a lot, because you’re exposing them to something unknown. You have to hope that they’re patient and open to liking something that’s not familiar to them.

How does it feel to have influenced so many players?

It feels good, because I feel like I’ve helped a lot of people learn how to play the bass. Those Nirvana bass lines I wrote were really easy, but they were catchy, and so many players got their start learning them and following along with them. Now they’re on YouTube and kids are still learning from them. That’s how I learned, too, just playing along with music in my room.

Your 1993 MTV Unplugged performance was a historic moment. What was that like?

We went into it so nervous and shaky. The rehearsals didn’t go well at all, so to help prepare myself I invited Cris and Curt Kirkwood of the Meat Puppets to my hotel room just to jam out the songs with me to get the details down.

For David Bowie’s “The Man Who Sold the World,” I sat on the edge of my bed the night before the show and tried to figure out what the hell the bass was doing. I knew I couldn’t touch Tony Visconti’s bass line, so I figured out the basic elements of the song that stand out, which is that bass run and those flourishes that he does. I knew if I could get the bass run down, it would bring it all together.

I sat for a half hour and played it over and over again, and I got it locked in. Then, playing the Nirvana songs, I just played everything faithful. I like improvising, and that’s how you come up with new music, but once I figure something out that works or I write something and lock it in, I never change it. I still can’t believe we pulled that show off.

What was your approach to bass in Nirvana?

My approach was making things bigger and louder, because we were a trio. We had an intense singer and heavy drums, and I had to figure out how to fill things out a little. I have a few tricks that I used over and over, like I’m some kind of hack musician, but they always work.

One of them is that there’s a time to follow the guitar riff, but the bass is not just a bastard stepchild of the guitar, and as a bass player you have to know that. The kick drum is the boss and you have to follow it, but then you can riff off the guitar riff, or riff off the vocal melody, which a lot of times is the hook.

And then if you can find the bridge between the guitar riff and the vocal melody and the rhythm of the kick, then you can pull something off that brings another dimension to the music that isn’t just the bottom end of the guitar. That’s one of my tips: Listen to the vocals. If you can riff off the vocals, then you’re on to something.

I was lucky because I had Kurt, who was a great lyricist and he was great at writing melodies, so it made doing that easy for me. And then I had Dave on drums and he made the rhythm part stick. I just had to find my place between the two of them within the song.

Was that how you always played, or was it something you discovered over time?

I think I learned that through listening to Paul McCartney and Geezer Butler and John Entwistle, who all do that. Entwistle played lead bass, basically. Butler was a sludgemeister, and he would go along with the riff but play a lot of fills. And McCartney was so great at covering the foundation but adding little catchy melodies to his bass parts.

So you look for a balance of supplying foundation and adding flair?

That’s my next tip: You always have to search for what the song needs. Do it for the song, and don’t do it for yourself or to showcase your chops. You can transform a song with subtle little changes and rhythmic things if you are mindful of the song. Just go for the song, and then it’ll all come together and you’ll be successful.

Some players just do math and don’t do music. They try to squeeze so many notes in, and sometimes it works. A lot of it is visceral, too. The bass can change the whole personality of a song. Like, one of the best bass players in the world is Flea—he’s incredible!

He can be doing total slap bass, but he finds a groove and he locks it in. You can tell he always works for the song. Chili Peppers are a song band, and he makes the bass something that the listener wants to follow. That’s part of being a song band.

Nirvana was definitely a song band.

Absolutely, 100 percent. Every song came from us writing a song, not just parts. That’s all we cared about. That’s what I love about Giants In The Trees: It’s all songs for the songs.

Speaking of Paul McCartney, what was it like collaborating with another living legend?

Incredible. Dave [Grohl] sent me an email asking if I wanted to play with Paul McCartney in L.A., and I said, Dude, I’ll walk there from Washington if I have to. So I flew down and we were standing around figuring out what to do, and I kept thinking, Please don’t make me play bass, please don’t make me play bass. That’s like being asked to do karate with Bruce Lee—you’re going to get your ass kicked. Yep, I’m going boxing. Who’s your sparring partner? Muhammad Ali. Good luck with that!

So of course he asked me to play bass. Paul had this slide guitar that he was playing, and Dave was playing drums, but it wasn’t working for us. Then I realized we were playing in D, so I did the old grunge trick and I drop-tuned my bass to D.

I played some riffs, and boom! Paul got into it, Pat Smear was feeling it, and Dave laid down some serious grooves. Then Paul shot me a riff and I shot him a riff and everything started clicking perfectly. And we were suddenly a band!

That must have been a surreal moment.

It was. Paul stopped everything and said it dawned on him that he was part of a Nirvana reunion, and he was right because Dave, Pat [who had toured with Nirvana], and I hadn’t played like that for years. Then I got really sentimental.

We had the old band back together now, and we had this cool left-handed guitarist, who was actually Paul McCartney, and he was doing vocals. I had to pinch myself. We ended up winning a Grammy for that, too, which was “Cut Me Some Slack” [McCartney/Grohl/Novoselic/Smear, Sound City: Reel to Reel Soundtrack, 2012].

And then we played live at Madison Square Garden for the Hurricane Sandy benefit on 12/12/12, and there was speculation that Nirvana was reuniting, with Paul taking over for Kurt. It was just a lot of fun. It was creative and compelling.

So it wasn’t so bad playing bass for him after all?

He said he liked my bass lines. Paul McCartney said that! You can put that in a pull quote [laughs].

What’s it like playing in a rhythm section with Dave Grohl?

Dave’s amazing. He’s such an animal on drums. We’re always so intense together, and it just takes off. Once the train leaves the station, you have to just hang on and go with it.

It’s like in surfing: When you catch a wave, you have to ride it out. There’s so much power behind his drumming, and that’s the key to performing—harnessing that power and riding it. We’ve always clicked like that.

You have a signature gritty, cutting tone. How do you achieve it?

I think it comes from my attack, because I always strike the strings really hard. I don’t know how or why, but maybe I just want it to be loud, and I know if I hit that thing hard, it will project more. I dump out all the midrange and do the “scoop” EQ [smile-shaped curve].

I use my left thumb a lot for bending, I do a lot of vibrato on the notes, and I do a lot of slides; I’ll slide up to the note, slide off it, or slide in between notes. You can hear a big example of that in the verse bass riff of “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” where I try to really lock it down with the drums, and I never take my fingers off the strings.

I’m sliding up and down between the main root notes. It works as kind of an accent where it smoothed everything out.

Do you believe you’re a better player now than ever before?

I like to think so. The years really make the musician, and probably the biggest thing that’s changed my playing is all of the time that I’ve been doing this. At the height of Nirvana, I hadn’t been playing for ten years even.

I started playing in 1986, so I was maybe eight years into it at the time. Now I’ve been playing bass for over 30 years, so you get that maturity and you become a better, more tasteful musician. It just takes time. On accordion I barely get by, and I’ve been playing that for around 40 years. Hopefully I’m even better when I’ve been playing bass for that long.

Equipment

Bass Gibson RD Standard, Ibanez Black Eagle, Squier Gary Jarman Signature, Guild Acoustic Bass Rig Ampeg SVT-4PRO, Ampeg SVT 810 Effects Boss DS-1 Distortion Strings Rotosound Swing Bass 66 Accordion Petosa Artista

Bass Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful bass publication for passionate bassists and active musicians of all ages. Whatever your ability, BP has the interviews, reviews and lessons that will make you a better bass player. We go behind the scenes with bass manufacturers, ask a stellar crew of bass players for their advice, and bring you insights into pretty much every style of bass playing that exists, from reggae to jazz to metal and beyond. The gear we review ranges from the affordable to the upmarket and we maximise the opportunity to evolve our playing with the best teachers on the planet.

“I was playing stuff I don’t think James Brown understood. He told me, ‘You have to play the one – you’re playing too much’”: Six years after he quit touring, Bootsy Collins reflects on James Brown and George Clinton, and what he gets out of playing today

“When I first heard his voice in my headphones, there was that moment of, ‘My God! I’m recording with David Bowie!’” Bassist Tim Lefebvre on the making of David Bowie's Lazarus

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)