Nils Lofgren talks touring with Bruce Springsteen, collaborating with Lou Reed and why he favors thumb picks

The E Street Band guitarist on the background to Blue with Lou and its five 'lost' songs, co-written with Reed more than 40 years ago

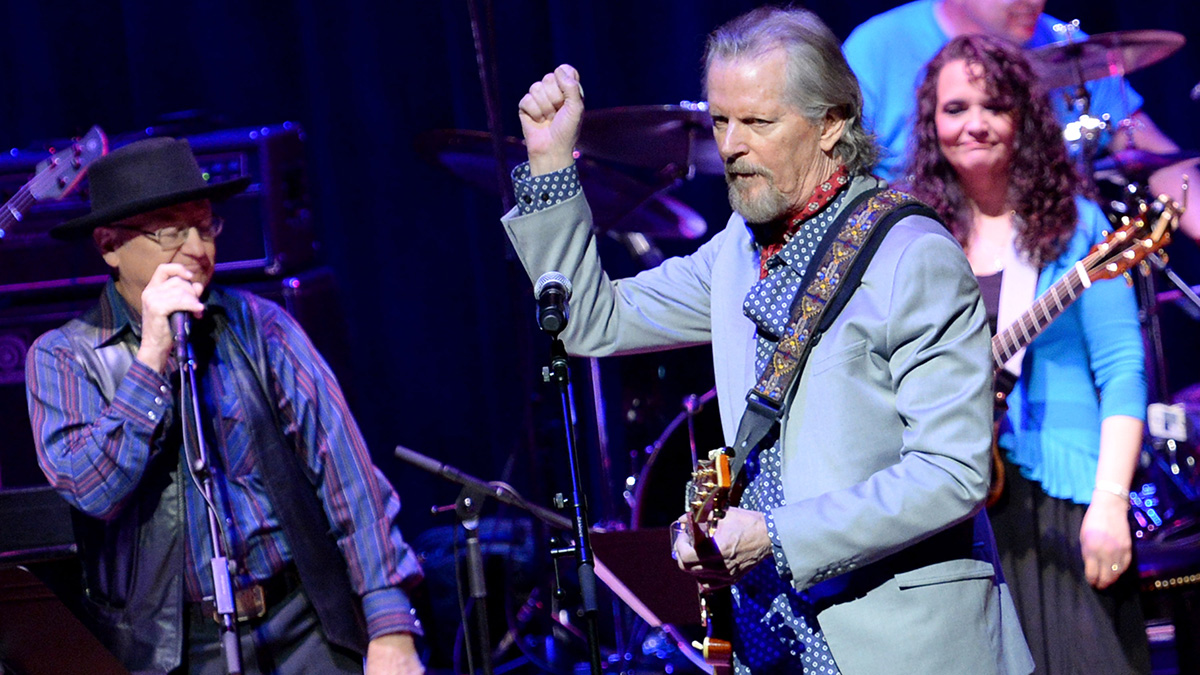

Nils Lofgren - the singer/guitarist who worked on Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush in 1970, co-wrote with Lou Reed in the late-'70s and went on to enjoy a 35-year (and counting) career with Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band - should be a household name by now. The fact that he’s not is, frankly, one of life’s little mysteries.

There was, however, a time when it seemed Lofgren’s name was bound for the brightest of marquees. His albums with Grin from 1970 to 1973 earned critical acclaim and fueled his growing reputation as an artist to watch.

Subsequent solo albums, from 1975’s Nils Lofgren to 1979’s Nils, were uniformly excellent and featured some of his most-loved tracks, including I Came to Dance, Back It Up and Keith Don’t Go. Lofgren’s profile was high, he was touring the world and was considered a gifted guitarist and singer. He had the looks and the hooks - but he couldn’t score the hit.

Lofgren has continued to release quality albums ever since, interspersed with his work with the Boss, other Neil Young projects and some time with Ringo Starr’s All-Starr Band. He’s bemused but philosophical on the vagaries of a fickle and capricious business, where fortune doesn’t always favor the best.

Living an idyllic lifestyle on his ranch in Arizona with wife Amy and a collection of beloved dogs, he’s grateful for the opportunities that have come his way and the continued chances to work with artists he’s admired and respected.

Lofgren’s new album, Blue with Lou, features a collection of “lost” songs he wrote with Reed more than 40 years ago, plus a couple of Reed-inspired tracks. In late 1978, Lofgren and Reed co-wrote 13 songs. Three wound up on Reed’s 1979 album, Bells; another three appeared on Nils.

Lofgren recorded two more songs in 1995 and 2002 - which means five Lofgren/Reed compositions have simply been gathering dust for years. When Reed died, Lofgren starting thinking it might be time to revisit them. “I’d always hoped someday Lou would call and we’d get the rest of these songs finished,” Lofgren says. “But, of course, we lost him in 2013.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Blue with Lou certainly stands up to the best of your solo albums. How happy are you with it?

I’m much better when I sing and play live and don’t have to worry about the details

"I’m really pleased you think that. It was two years from conception to completion. I wanted to get to a place where we could record live in the studio - bass, drums, my guitar parts and the singing, all at once. I’m much better when I sing and play live and don’t have to worry about the details. I wanted to get down all these songs that I’d written with Lou.

"It’s been a long time since I put out an album, so I took my time, eased into everything and made sure I had everything ready before the band got here."

One of the most striking things at first listen was the use of a male choir, which gives it a kind of epic feel with a hint of the Jordanaires’ work with Elvis Presley. What inspired that?

"I don’t believe in astrology much, but I’m a Gemini and I’m supposed to have kind of a split personality - though it often feels like there are more than two people in my head.

"I have a real gentle, peaceful side; I love ballads and country and I love real raunchy rock ’n’ roll and everything in between. I’d been listening to a lot of old Elvis and Ricky Nelson - Ray Charles, too - that kind of peaceful male-choir sound.

"I thought it was boring to me to do the 'oohs and ahhs' myself. It’s a fresh touch that I like hearing with my new bunch of songs."

When you presented the songs to Lou all those years ago, what did you give him? Melodies, a backing track? How formed were the ideas?

Lou Reed called me at about 4:30am - woke me up - and dictated all 13 sets of lyrics over the phone

"Bob Ezrin was my producer and he suggested we meet up with Lou. We realized I write music all the time and it comes pretty easy for me, and for Lou, he’s writing lyrics all the time - he was the exact opposite.

"I had 13 songs that were done, in so far as they had titles, or a verse or lyrics. I sent him a cassette and 'la-de-dah’d' for some ideas where there were no lyrics. Lou knew all the words were open to change. Three or four weeks later he called me at about 4:30am - woke me up - and dictated all 13 sets of lyrics over the phone.

"There was a lot of work put into the tape over many months before he got it. At that time Lou said he’d been looking for some inspiration, so that tape came at the right time for him."

Talk Through the Tears, Rock Or Not and Right Now are certainly standout tracks. What are your favorites at the moment?

"Right now, just the fact that it’s done - it’s been a long time coming - I’m digging the whole record. The ones you mentioned are some that I particularly like.

"Rock Or Not was one that I had the title for for a long time. I knew it would have to be a rocker, but then it turned into kind of a protest song. I’ve been pulling my hair out with the politics of the planet.

"My wife Amy, who does all my merchandise, is very active on Twitter against the madness we have now, and that all played into the whole protest dimension. I think that should be a strong song live.

"Pretty Soon just kind of came out one day. People hear it with different perspectives; I had the perspective of it being about a wide-eyed kid who’d just enlisted in the army and missed his girlfriend and realized how it wasn’t all fun and games."

The album is on your own Cattle Track Records label. Is that due to the politics of the business, a desire to control things or just economics?

"It’s a bit of all of those things. First of all, I’m 67, I’ve been on the road for 50 years and I never had a hit record, so record companies aren’t really interested in me. The few labels that might offer me something, they’re just awful deals.

"We live in this beautiful old artistic community in Arizona - Cattle Track [Arts Compound] - so that was the name. It’s kind of homegrown. We can deal with everything hands-on ourselves and it’s a lot simpler than dealing with the madness of the music business.

"I’ve got a funky home studio; you can make records without having to go to LA or New York and spend $200 an hour. I got to do that as a kid with a record company. It’s fun but it’s also not conducive. We banned click tracks. We didn’t even try for a take of a song for eight days.

The excitement of the '50s records was that they just went for it with a handful of mics - not overdubbing and redoing parts endlessly

"We learned about 18 songs and really tore them up trying different ideas and arrangements, so that by the time we started recording we had 18 songs good to go. If we didn’t think it was working, we’d move on to the next song. It was a very old-school approach with some dear old friends in our home.

"The excitement of the '50s records was that they just went for it with a handful of mics - not overdubbing and redoing parts endlessly. We’ve lost a lot of that these days, so that was a factor in trying to capture some of that magic."

I first came across you in the early '70s. At that time you had a really high profile. Why do you think that it never crossed over into mainstream success?

"At the end of the day, it’s not enough heavy-rotation airplay. If you can’t get the constant airplay you need, you can’t get that hit. I’m not even gonna think about blame anymore. I’ve done my level best for each project; I’m grateful for what I’ve got, and I’ve done a lot of great work with other people. I’m not bitter or anything.

"It’s been great to have done so many different things and still be able to go out there and sing and play. 50 years ago, I never imagined I’d ever be talking to anybody about my music."

What’s interesting about your solo work is how much guitar there is in there. Not just the solos, but the fills, the intros, the rhythmic ideas. There’s a ton of guitar on those songs.

A lot of times if there isn’t a big solo, people don’t think there’s any guitar, and for me it’s about the song

"I’m glad you say that. A lot of times if there isn’t a big solo, people don’t think there’s any guitar, and for me it’s about the song. On City Lights, I didn’t feel it needed a guitar solo, so I got my old friend [sax player] Branford Marsalis to play on it. That served the song better for me. It’s what makes the song work that matters."

The thumb pick is central to your approach. Did you always use it, or did you start off with a regular pick?

"My dad had a beat-up old acoustic with a thumb pick in it. My brother Tommy started playing guitar before me and he was using a flat-pick. I picked up that old acoustic and started learning with the thumb pick. I’m left-handed but I started playing right-handed. It sounded awful for about nine months, but then I started to get it and I was making music.

"A local teenage guitarist told me you can’t play rock ’n’ roll with a thumb pick; you need to change to a flat-pick. I thought there’s no way I’m going to spend another nine months getting back to where I was, so I stuck with the thumb pick. It was just a happy accident that led to some fingerpicking styles down the road."

So much of what is distinctive about what you do - the harmonics, the volume swells - is actually much easier and more logical with the thumb-pick.

"Yeah. Roy Buchanan, who was one of my top three heroes alongside Jeff Beck and Jimi Hendrix, lived near me. I used to see him play a lot, I became friends with him and he showed me how to do harmonics with a flat pick. I couldn’t do it, but I found my own way with the thumb pick. That was the first time I heard harmonics sound like bells.

"I took some lessons as a kid and my teacher had this great album, Chet Atkins Picks the Beatles, so I tried to learn Can’t Buy Me Love. It was a great exercise in learning how to pick the melody interdependent of the bass. It took me months and months to master that. It really expanded my vision to be able to play themes and rhythm with the thumb pick quite a bit."

Is the gap between your solo projects dictated by how much work you’re doing with Bruce - or anyone else?

It was just a beautiful accident that I ended up meeting Neil Young and doing After the Gold Rush when I was 18

"I started out with Grin and it was just a beautiful accident that I ended up meeting Neil Young and doing After the Gold Rush when I was 18.

"I remember I was living in Topanga Canyon with David Briggs, Neil Young’s producer. We’d get in his little VW Beetle and drive through the Topanga Hills to Neil’s house, and I remember saying to David how it’s so neat to not be the band leader. Just to be in a great band - not to have to worry about the setlist, the schedule - every detail. There’s a lot of non-musical work there. I remembered that through the years working with Bruce and Neil and Ringo’s All-Starr Band; it’s a very freeing and inspiring thing.

"I always kept doing my own music when the opportunity arose. I mean, I picked my spots - I wouldn’t just go off and play with anybody. I knew and loved the music of the people I played with.

"Ringo and the Beatles is the reason I fell in love with rock ’n’ roll. When I come back to my own music, I feel extra-inspired and refreshed."

Sometimes at Springsteen gigs you’ll do a cover that you haven’t played before, like when you did the Clash’s London Calling out of the blue in the UK. How much notice do you get?

"Usually what happens is that maybe, if you’re very lucky, he’ll send you a text the night before. But more often, you might find out a couple of hours before the soundcheck.

"He’ll say, 'Hey, I’m thinking of taking a shot at London Calling tonight so you might want to check that out.' Sometimes he’ll say, 'Pass it on.' Then we’ll try to hear a live version and the album version - it evolves at the soundcheck. Sometimes we can just do audibles if it’s something easy like Louie Louie. With something like London Calling, you need a bit of notice. Usually that notice is quite late in the day! London Calling was a really great one."

Guitar-wise, you’ve always been primarily a Fender guy, particularly Strats. Any changes there?

"That’s my favorite guitar, the Strat. I used a Gretsch Black Falcon a lot on the new album, and a Jazzmaster. For most of it, though, it was a Strat. On Magic and Working on a Dream, Bruce added some Gretsch parts. When he’s singing, me or Stevie will cover some of the more intricate parts.

On the Wrecking Ball tour I thought, 'I’ve gotta get me a Falcon' for that Buffalo Springfield look

"I had a Gretsch, an orange one [6120] that I’d bought. Then on the Wrecking Ball tour I thought, 'I’ve gotta get me a Falcon' for that Buffalo Springfield look. We tend to be a darker-looking band with Bruce; we did have a free-for-all on the Born in the USA tour where we wore what we wanted, but that got so out of hand that Bruce said, 'You know what? Wear whatever you want as long as it’s black.' So I thought I’ll get a Black Falcon with the gold trim - very Elvis in Vegas. It’s just got a great look."

It’s obvious you’re grateful for the opportunity to have spent your life making music.

"Now that I’m 50 years down this road I want to say that what I’ve got is a gift for music from my folks and some higher power.

"I’m not religious. I don’t like organized religion, but I believe in some kind of god and spirituality. I’m just cultivating a gift I was given; I didn’t create it - I’m just trying to caretake it. The fact that I could turn it into a 50-year career is a beautiful thing. I don’t think it’s of my own making, but I’m trying to do the best I can with it."

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.

“This particular way of concluding Bohemian Rhapsody will be hard to beat!” Brian May with Benson Boone, Green Day with the Go-Gos, and Lady Gaga rocking a Suhr – Coachella’s first weekend delivered the guitar goods

“A virtuoso beyond virtuosos”: Matteo Mancuso has become one of the hottest guitar talents on the planet – now he’s finally announced his first headline US tour