Metallica's Kirk Hammett Talks 'Ride the Lightning,' Cliff Burton and Taking Guitar Lessons from Joe Satriani

Tucked in a nondescript industrial tract north of San Francisco near San Pablo Bay, Metallica’s headquarters is an oasis for both thrash fanatics and gear heads of every stripe.

The massive studio—dubbed HQ by the band—has been Metallica’s base of operations for writing, rehearsals, demoing and all-purpose hanging since late 2001. In a rare case of reality trumping fantasy, it is a place that exceeds expectations.

We’ve been invited to HQ to talk with Kirk Hammett about the 30th anniversary of Metallica’s classic sophomore album, Ride the Lightning.

Released July 27, 1984, the album showcased their growing musical maturity and willingness to take chances. With brazen disregard for convention, Metallica delivered the pure thrash attack for which they were known while simultaneously branching into progressive, melodic and, ultimately, more marketable territory. Ride the Lightning didn’t just change the band’s trajectory—it reset the course of metal itself.

We arrive at HQ before Hammett does, so while we wait, a staff members gives us a tour of the facilities. Everywhere we turn there are choice pieces of memorabilia or references from one of the eras of the band’s rich history. Fan-made banners collected from concerts around the world hang throughout the massive complex.

There’s the kitchen table over which drummer Lars Ulrich confronted guitarist James Hetfield in a particularly tense scene from Metallica’s 2004 documentary, Some Kind of Monster, as well as the electric chair from Hammett’s Kirk’s Crypt horror memorabilia collection and the Lady Justice prop head from the 1988-’89 Damaged Justice tour.

But the real gold is in the band’s storage room. Not unlike the oversized aisles of a Sam’s Club, the shelves in this room are packed to the rafters, only with gear. A quick scan of the inventory reveals a mint of mouth-watering guitars, from vintage Flying Vs, Les Pauls and Strats to a staggering array of ESPs, Jacksons and Warwicks.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

HQ’s massive main rehearsal area is bursting with even more gear. Today the room is staged with the band’s acoustic arsenal, as they’re in the middle of rehearsals for an upcoming unplugged gig. Fitting nicely with the objective of our mission, the original Ride the Lightning stage backdrop is hanging across the rear of the rehearsal room.

As we take in HQ’s scope and content, we’re reminded that Metallica aren’t your average working band. At this point they’re a metal institution and one of the most successful selling artists in the world. But Number One albums, feature films, massive tours and sprawling rehearsal studios weren’t always a part of the band’s lifestyle. When Ride the Lightning was released 30 years ago, Metallica were a bunch of young musicians from the San Francisco Bay area, hungry to push the limits of the nascent thrash metal genre and willing to go to any lengths to make that happen.

“Around the time we were writing Ride the Lightning, I was taking guitar lessons from Joe Satriani,” Hammett says after he joins us at HQ. “I didn’t have a car, so I had to ride my bike to the lessons. And it took me over an hour and a half, because I lived, like, 25 miles away. The lessons were in a guitar store. So I would ride the whole way there—all huffing and puffing and sweaty—and I’d grab a guitar off the wall. After we finished, I’d grab my lesson papers and bike 25 miles again home!” He laughs at the memory. “It was hilarious. I felt like Lincoln walking 18 miles to go to school or something.”

Back then, Metallica were a quartet of hellions who ignited the underground thrash metal movement with their blazing, neck-breaking debut, Kill ’Em All, which was released on indie label Megaforce in 1983. But unlike Anthrax, Slayer and other thrash acts that were rising around that time, Metallica had a broader, more ambitious vision of what their sound could encompass. They just had to figure out how to pull it off.

By all accounts, their bassist Cliff Burton—who died tragically in a 1986 bus accident—was integral to helping the band expand its horizons. “Cliff studied music in college,” Hammett says. “I had a grasp of music theory, thanks to Joe, but Cliff went the whole length and learned musical theory and everything. And he was way into harmonies. James really absorbed the dual-harmony thing and took it to heart. He made it his thing, but it was originally Cliff’s. Cliff also inspired James greatly on counterpoint and rhythmic concepts.”

In early 1984, armed with a batch of new material and fresh techniques, the band decamped to Copenhagen, Denmark (at the prompting of Lars, who is a Danish citizen), and began tracking the record with producer Flemming Rasmussen at Sweet Silence Studios. In two sessions spread over several months, Metallica cut the eight tracks that would comprise Ride the Lightning. The record contained Kill ’Em All–style ripping thrash (“Trapped Under Ice”), but it also incorporated acoustic sections (“Fight Fire with Fire”), epic compositions (“Creeping Death,” “For Whom the Bell Tolls”), exciting structures (“Ride the Lightning”), expansive instrumentals (“The Call of Ktulu”) and, most shockingly, a power ballad (“Fade to Black”).

Metallica may have entered Sweet Silence as just another thrash band, but they left as one of the most sought-after acts in the scene. In the months following Ride the Lightning’s release, they were picked up by the major label Elektra and signed to powerhouse management company Q-Prime. With the die-hard metal underground already in their corner and their new backers poised to launch them out to mainstream audiences, Metallica set off on the path to becoming the biggest metal band on the planet.

Today, Ride the Lightning ranks as a classic album in the metal genre. Looking back through the lens of the past 30 years, how has your view of the Ride the Lightning era changed?

It’s interesting. Just this morning I was telling my kids what I was going to do today. I’m like, “These people are taking a picture of me in an electric chair!” They’re both young, so of course they said, “Why?” I explained it’s because we have a song called “Ride the Lightning” and that’s another way of saying, “You’re getting electrocuted in an electric chair!” Then I had to play them the song and sing them the lyrics. They’re sitting there looking at me, like, Wow. [laughs]

So I’m sitting with them, listening to that “Ride the Lightning” guitar solo, and I was like, I have absolutely no recollection of putting all those harmonies on there! [laughs] When we were putting that song together, we had the intro riff, the verse, the chorus, and a part of the instrumental bridge. When the whole thing slows down and there’s that solo section, I remember I pretty much played that solo as it is off the bat.

When I recorded that in 1984, I was 21 years old. That’s crazy. In 1984, a guitar solo like that was something. If you put it into context of what was going on back then, it was very modern sounding. Of course, if you put it into today’s context, it sounds like classic rock. [laughs] It’s not like today’s norm, with sweeping arpeggios and 32nd notes everywhere. I also have to say that when I listened to it this morning, I realized that the actual sound of the album is still good. After all these fucking years, it still holds up sonically.

You were still on the indie label Megaforce when you recorded Ride the Lightning, which I assume meant you weren’t working with a big budget. How’d you end up flying to Copenhagen to record with Flemming Rasmussen? Was that a Lars connection because he’s Danish?

It was a Lars connection. Also, Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow had recorded a couple albums there—Difficult to Cure and Bent Out of Shape—and they’re recorded really well. At that time, studio time was cheaper in Europe than it was in the States. We were already over there, because we had just ended a European tour. Plus, we had the benefit of Lars being Danish, so we worked out a package deal with Sweet Silence Studios.

I remember we had landed in Copenhagen to record the album, and we needed a few days to get the songs together. We were in Mercyful Fate’s rehearsal space in Copenhagen. They weren’t there, so they lent it to us. So we were in there playing, and I look up and through the window I see this guy with his back to me. I could tell it was King Diamond, and I was like, Uh-oh, there’s the man himself. And then he turned around and he didn’t have his makeup on! I was like, Woah…unmasked! [laughs]

Did you guys do a lot of writing in Denmark? Or did you have most of the tracks finalized before you arrived?

I remember “Fight Fire with Fire” and “Fade to Black” were finished in the basement of a friend’s house in Old Bridge, New Jersey. I think it was this guy called Metal Joe [Chimienti]. Before we went to Europe to tour and eventually record in Denmark, we stopped on the East Coast to play some shows. We knew we needed to finish some of these songs.

We had most of “Fade to Black,” except the end part were the solo happens, and I came up with that there. I remember we were writing “Trapped Under Ice” there too. We were using that fast Exodus riff, and James came up with the chorus and I added that whole middle instrumental part.

Ride the Lightning was written in a few places: the house in El Cerrito, New Jersey, Copenhagen, and down in L.A. before James and Lars moved up to San Francisco.

Were you writing the stuff in El Cerrito around the same time you were taking lessons from Joe Satriani?

Yeah, absolutely.

Do you remember any specific techniques that he showed you that ended up on Ride the Lightning?

All the stuff I learned from Joe impacted my playing a lot on Ride the Lightning. He taught me stuff like figuring out what scale was most appropriate for what chord progressions. We were doing all sorts of crazy things, like modes, three-octave major and minor scales, three-octave modes, major, minor and diminished arpeggios, and tons of exercises. He taught me how to pick the notes I wanted for guitar solos as opposed to just going for a scale that covered it all. He taught me how to hone in on certain sounds and when to go major or minor. He also helped me map out that whole chromatic-arpeggio thing and taught me the importance of positioning and minimizing finger movement. That was a really important lesson.

You guys made a pretty serious jump in songwriting and style between Kill ’Em All and Ride the Lightning. Lars has said that Cliff Burton was an important force in pushing Metallica in this new progressive direction. What was your experience like working with Cliff during this time?

Cliff was a total anomaly. To this day, I’m still trying to figure out everything I experienced with him. He was a bass player and played like a bassist. But, fucking hell, a lot of guitar sounds came out of it. He wrote a lot of guitar-centric runs. He always carried around a small acoustic guitar that was down tuned. I remember one time I picked it up and was like, “What is this thing even tuned to, like C?” He explained that he liked it like that because he could really bend the strings. He would always come up with harmonies on that acoustic guitar. I would be sitting there playing my guitar and he’d pick up his bass and immediately start playing a harmony part. And he would also sing harmonies. I remember the Eagles would come on the radio and he would sing all the harmony parts, never the root.

The harmonies are really apparent on this record, too, on tracks like “Creeping Death.”

Totally. He wrote that “Creeping Death” harmony part and the harmony in the intro to “Ride the Lightning.” He even helped me with a lot of the harmony stuff I played in the solo to “Ride the Lightning.” I remember, I thought he’d just grab a bass and show me. But no, he had me write out all the notes in my solo on a piece of paper. Then he grabbed a pencil and went through and notated it, “If you’re playing E, then G, then A, then C…” I’m looking at him like, What? But I took the paper and worked it all out. And you know what? It was perfect.

What was the actual recording experience like when you finally entered Sweet Silence Studios? It was winter and you were far away from home. Did the isolation make for a super-creative experience or a lonely one?

It was super creative, but it was also very lonely and depressing for us because we were one step away from being homeless. We had all embarked on this to become signed by a record company, make records and go on tour. But at the time we were living a hand-to-mouth existence, and all of us were worrying about what was going to happen. Would a gig show up? Or would we get a phone call saying, “You guys are too extreme.” There were a lot of different factors.

We were also lonely because we were so far away from home. At least Cliff, James and I. We all had girlfriends at the time, and we were away for three or four months at a time. It was that sort of lonely feeling you get from being on the road and away from loved ones for a long time. I think that basic feeling was channeled into the album.

Where were you staying while you were over there?

We lived at the studio. Well, first we were staying at our friend’s house, but we totally thrashed it. Then we were living upstairs in an empty floor of the studio. That was crazy, because it was the middle of winter and we’re living among piles of asbestos and particleboard. But we rallied around each other, because that’s all we really had at that point. All of us were taken out of our lives, like maybe a year and a half prior with Kill ’Em All, and we fended for ourselves. We were so young and just trying to figure it out. A lot of the time we didn’t know what we were going to do, and we were fearful. I think that’s why we really embraced the consumption of alcohol so much. [laughs] We drank a lot. Actually we drank tons up to 1998. [laughs]

It’s interesting that you say that, because nowadays Metallica are an institution. There are probably fans born in 1998 that never realize at one point you were just another struggling band.

Totally. You know that we actually recorded Ride the Lightning in two different time periods? We started recording, then we took a break and went over to England to do a tour with the Rods and Twisted Sister. But when we got to England, the tour got canceled. We had no money, so we got stuck and couldn’t get back to Denmark. So we stayed in England for a couple weeks, and I just hung out and drank a lot of English beer. [laughs]

But yeah, I remember a time when I only had one fucking guitar. I had to borrow a second guitar in the studio for Kill ’Em All, because my guitar didn’t have a whammy bar. Even when Ride the Lightning came along, I just had three guitars. I had the black-and-white Gibson Flying V, a red Fernandes and the Edna, which was a black Fernandes Strat that was on the cover of [The $5.98 E.P.:] Garage Days [Re-Revisited]. Those were my three guitars.

Speaking of gear, is it true that all your Marshall amps were stolen in Boston right before you headed over to Denmark?

Yes. And when we got to Denmark, they only had a few amps in the studio. That country is so small that all the major music stores are in Copenhagen. So Flemming Rasmussen called all the stores and said, “Bring down all the Marshalls that you have.” We tried ’em all and found a couple that were good. We just worked with what we had. Oh, there was this guy in some band that had a great-sounding Marshall that we used. We dubbed it the “Best Sounding Marshall in Denmark.” We used his head for the majority of the album.

What other gear were you using back then?

I had the [Dunlop] Cry Baby wah I’ve always had and an [Ibanez] Tube Screamer. On Kill ’Em All, I used a Boss Super Distortion, because my Tube Screamer got stolen. But on Ride the Lightning and on every album since, there’s always been a Tube Screamer for the solos. Actually, we were just rehearsing some acoustic stuff for an acoustic gig. I needed a boost to drive my solo, and what do I go for? The Tube Screamer. And it worked perfectly.

Ride the Lightning was the first record you had writing credits on. [Hammett replaced original lead guitarist Dave Mustaine in 1983 prior to the recording of Kill ’Em All.] At that point were you feeling a lot more comfortable about bringing your ideas to the band?

Absolutely. Actually, the title “Ride the Lightning” was my idea. I had taken it from a passage in a Stephen King novel, The Stand. There’s this prisoner, and the line’s something like, “He was stuck on death row and ready to ride the lighting.”

Anyway, when I joined the band, those guys went out of their way to make me feel comfortable. It wasn’t like when Jason [Newsted] joined the band [after the death of founding bassist Cliff Burton], and we weren’t as far established as we were when [bassist] Rob [Trujillo] joined.

We hung out all the time back then. I remember right after recording Kill ’Em All, James was like, “Check this out,” and played me the riff to “Creeping Death.” But it was played really slow, like half time. It just naturally sped up over the course of time.

The middle section of “Creeping Death” came from some material you were working on during your time in Exodus. How exactly did it find its way into that song?

We had the rough outlines of a few songs, like “Creeping Death,” “Ride the Lightning,” “Fight Fire with Fire” and “Fade to Black.” As we were getting those songs together, I gave them a bunch of riffs. Not only did they listen to my riff tape but they also listened to the Exodus demo tape. That’s how certain riffs got taken out of the demo, like the fast riff in “Trapped Under Ice” and the “Die by my hand” riff from “Creeping Death,” which I wrote when I was 16 or 17 years old.

“Ride the Lightning” is also partially credited to your predecessor, Dave Mustaine. Were you conscious about constructing the solo in a way that really distinguished yourself from him?

He had nothing to do with any of the guitar solos on Ride the Lightning. That was more of the situation with Kill ’Em All. For that record, I was the new guy on the block. I thought, Okay I’ll start the solos the way Dave did, and then I’ll go somewhere else. His approach and my approach are completely different when it comes to solos. For me, Ride the Lightning was the first time I had a blank slate to come up with guitar solos. And I had a fucking field day.

The opening track “Fight Fire with Fire” begins with an acoustic intro, which is a huge statement coming on the heels of the thrashing cuts that made up Kill ’Em All.

That acoustic piece was Cliff’s! Cliff wrote that on the down-tuned acoustic guitar I was talking about. He had a really good grasp of playing the guitar, and a good grasp of classical modulations. That intro was his piece. We heard it and stuck it onto “Fight,” and it worked fantastic. We knew that was going to be the opening track. There was no question about it.

I heard a rumor that the instruments on “For Whom the Bell Tolls” were tuned slightly sharp to match the opening bell that chimes.

Nope. The chimes are slightly flatter. [laughs] Nah, it’s not us…it’s the chimes! Again, that bass intro was something Cliff had. He would play it all the time at soundcheck. I remember the first time he played it thinking, Wow. That’s a weird fucking riff. It was unlike anything I’d ever heard.

“Fade to Black” raised some eyebrows among fans at the time, because it was a ballad. But I’m wondering from a technical standpoint, was that track harder to cut because you all couldn’t hide behind tons of loud guitars?

I realized that some of the more difficult things to record are not necessarily the most technically demanding or challenging. I remember taking a ridiculous amount of time to record the three-note arpeggios that I play throughout the piece, because we wanted the intonation to be just right. During the recording, I remember I couldn’t hit those notes as hard as I usually did, because they would go sharp. So I took a lot of time hitting them softly, so they would chime perfectly. For something that sounds like it would take 15 minutes, it took about three or four hours. You never know how long something will take to record. The simplest things might take forever and the hardest you might nail in two takes.

That track was also controversial because of its lyrics, which dealt with suicide. Were you surprised when parental groups started accusing Metallica of promoting self-harm?

We weren’t expecting any of it. When they called us out for that, I was thinking, Why are these people even wasting their time? First of all, it’s just music. Second of all, it’s entertainment. Third of all…really? [laughs]

The instrumental “The Call of Ktulu” features a pretty epic guitar solo. How daunting was that to put together?

That was another track that had a rough skeleton of the main riff and the progression that modulates up. I remember first hearing it and thinking, This is a fucking amazing track! We kept working it, and it just got bigger, longer…and more pretentious. [laughs] But when you’re in your twenties, you don’t really have too much perspective to know when something’s pretentious. When it came to do the guitar solo, I was like, Fucking hell. This is a three-minute guitar solo! I knew I had to fill it up with melodic stuff and I couldn’t just rip throughout the whole thing or it would sound one-dimensional. I knew I needed to put some dynamics and melody in there to keep people’s attention.

Did you have to do a lot of prep work and chart things out before?

Actually, that guitar solo was the one that I was the least prepared to record. I only had half the solo, and we did a lot of it in the studio. And for some reason I decided to double the solo. It wasn’t good enough to play it all once; I had to play the exact same thing twice! The reason why I draw attention to the fact that I doubled the solo is because there’s this one note that I bend and it’s not quite there. But maybe it gives it an interesting Ktulu-ish effect!

It took you guys nearly 30 years to perform “Escape” live. Why the wait?

Yeah, we played it for the first time at Orion Fest [in 2012]. At the time we thought we’d write a song that was a little more accessible and melodic and less metal and grinding. It was also in the key of A, which is pretty rare for us. “Escape” was also the last thing written in the studio. I didn’t have anything for it, so that guitar solo was one of the most difficult to record. The song was pretty much an attempt to write something that would get radio’s attention. But it never really happened for us. They ignored that song…along with everything else!

Ride the Lightning was released on Megaforce in July 1984. But soon after, Metallica were signed by Elektra, which rereleased the album later that year. Did getting picked up by a major label drastically change your lifestyle?

Well, it felt good knowing that we finally got on a major, because that’s what we wanted to be on the whole time. But none of the majors were interested at first. The amazing thing is that it all happened in one night. We were playing Roseland Ballroom in New York City after we had recorded Ride the Lightning. That night, we got signed to Elektra, Q-Prime [management] and ATI, which was a booking agency back in the day. All three of those things happened that one night, and we didn’t even play that well! We went onstage and played, but we weren’t vibing like we usually did, and we were a little sloppy. So we came offstage and we were a little bummed out, saying, “Fucking hell, they’re not going to sign us. Are they even still here?” [laughs] Then Elektra came backstage and said, “Great fucking show, you guys were amazing!” [laughs] And Q-Prime said, “We are definitely working with you guys. Congratulations!” And we’re all looking at each other, like, Really?

After it all sunk in, we were really excited. Being signed to Elektra meant that our record would make it to a lot of places that wouldn’t be possible with an independent label. We knew we’d be able to tour a little better, like in a real tour bus and with better promotion. And, most importantly, we knew we’d be better off financially, so we could make a better-sounding record, which of course ended up being Master of Puppets.

Brad is a Brooklyn-based writer, editor and video producer. He is the former content director of Revolver magazine and executive editor of Guitar World. His work has appeared in Vice, Guitar Aficionado, Inked and more. He’s also a die-hard Les Paul player who wishes he never sold his 1987 Marshall Silver Jubilee half stack.

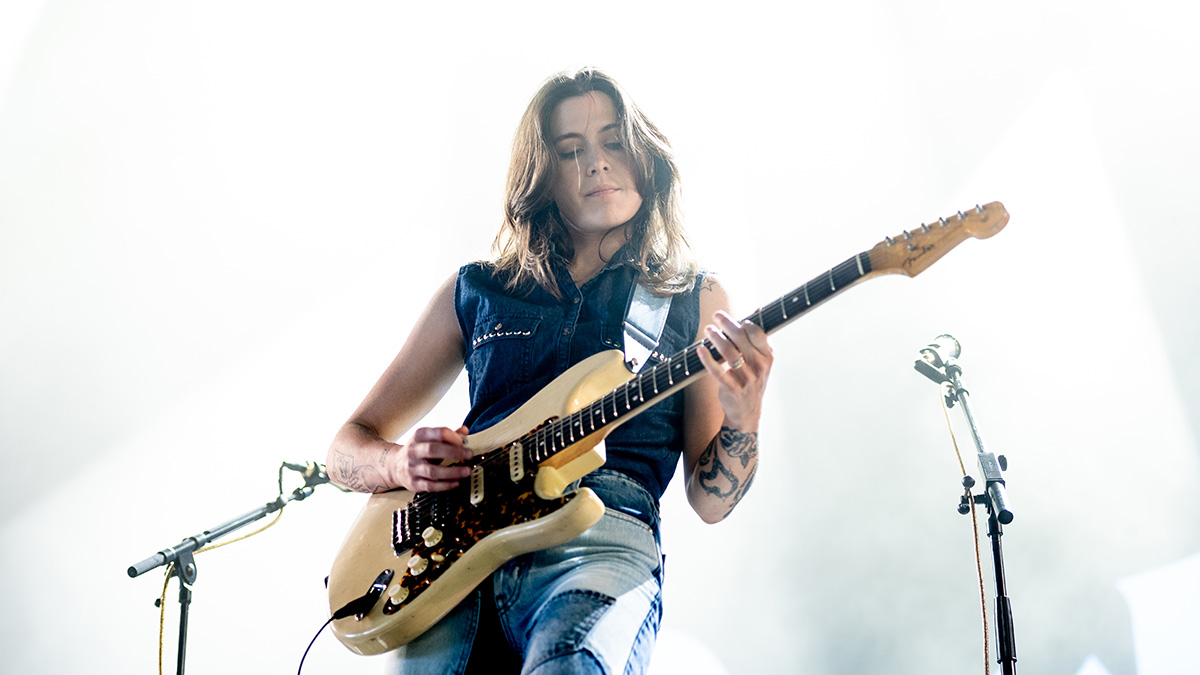

“A virtuoso beyond virtuosos”: Matteo Mancuso has become one of the hottest guitar talents on the planet – now he’s finally announced his first headline US tour

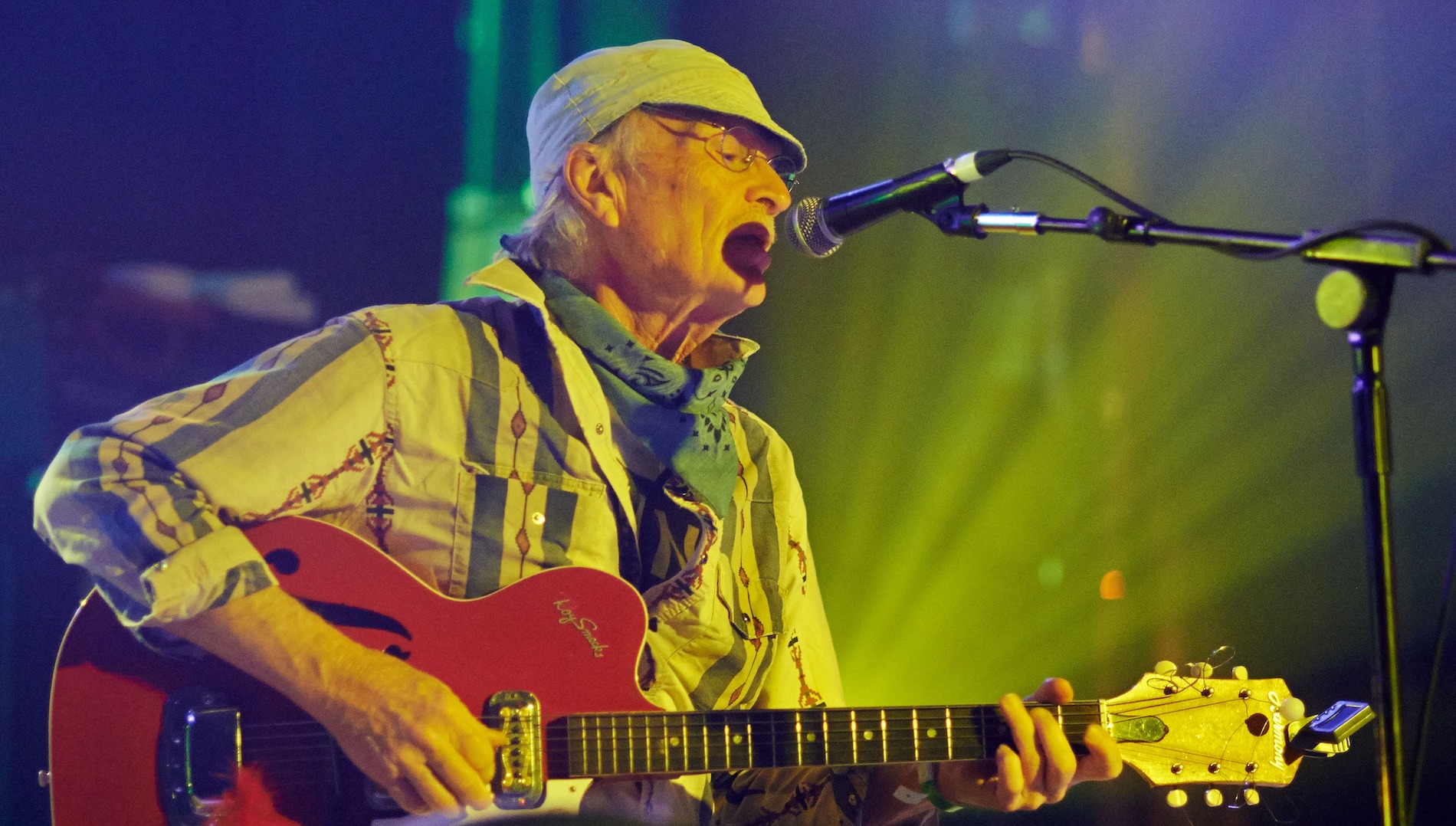

“His songs are timeless, you can’t tell if they were written in the 1400s or now”: Michael Hurley, guitarist and singer/songwriter known as the ‘Godfather of freak folk,’ dies at 83