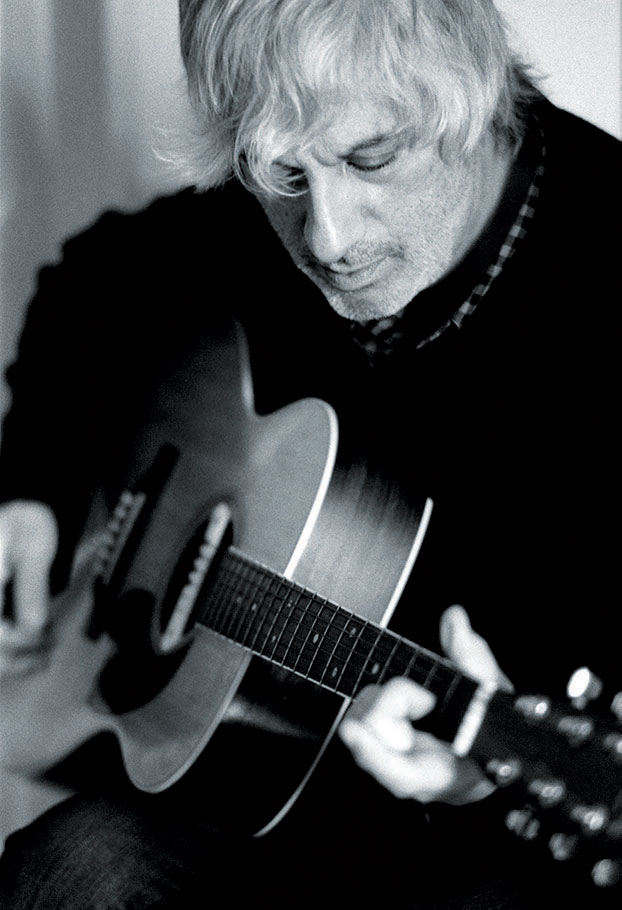

Lee Ranaldo Talks 'Electric Trim,' New Gear and Chances of a Sonic Youth Reunion

He was one of the key architects of the alt-Nineties guitar aesthetic in Sonic Youth and has a new album called Electric Trim, but what Guitar World readers really want to know is…

What are the origins of your Fender signature model Jazzblaster? —Alex Melton

One of the key guitars in my career has been an early-Seventies Fender Telecaster Deluxe that I had before Sonic Youth started, and that I played pretty much throughout Sonic Youth.

It was one of the guitars we lost in that big 1999 theft, when we had all our gear stolen. But it was one of the few guitars that actually got returned. I still play it onstage, and it’s on my new album.

But that guitar, with those Fender wide-range humbucking pickups, was really the impetus for me putting those pickups in my Jazzmasters. At some point in the mid-Nineties, one of the roadies was like, “You love the Jazzmaster body style, but you love the sound of those pickups in your Tele. Why don’t you just put those pickups in your Jazzmaster?”

And that became the basis for the signature model. I probably used my signature model on the new album too, as well as a white ’65 Jazzmaster I have.

What have you been up to since your last album, Acoustic Dust, in 2014? —Britney Bruce

Mostly making the Electric Trim album. The people who put together that Acoustic Dust record in Barcelona brought this guy Raul “Refree” Fernandez in to help with production. He’s pretty well known over there, although not so much over here. And we became fast friends.

At the end of the sessions, he said, “I’d love to work with you on a new record at some point.” Because the Acoustic Dust thing was just versions of my old songs from the last two records.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

So in 2015, Raul said, “Hey, I’m coming to New York for a few weeks. Should we bat a few things around in the studio?” I had been sending him some demos. And that’s where it started. I knew Raul was a lot more conversant with modern production styles than I am. Usually my records are made trying to capture the essence of a band playing in a room. He’s more into programming and samples. Raul and I worked on and off for about a year, as he was coming to New York, and later I was going to Barcelona.

Pretty much every song started with an acoustic demo by me. Starting that way, rather than with a full band, opened up a lot of new possibilities. We had all kinds of people coming in, playing and singing on the record, but mostly it was just Raul and me in the studio. We were treating live playing and Raul’s electronic sounds, samples and beats on an equal par.

There’s definitely a couple of songs where I couldn’t even say who was drumming on certain sections of the songs. It could have been Kid Millions on the verses, Steve Shelly on the choruses and maybe electronic drums on the bridge.

It’s the same with guitars. A lot of the rocking solo stuff is Nels Cline from Wilco. But occasionally it’s me, Raul or someone else. Alan Licht got a lot of tasty bits mixed into a lot of the songs. Some of the song files stretched to more than 100 tracks, which is crazy for me. I don’t usually work that way. With this record, we were looking to inject new sounds and new techniques into my songwriting. It paid off in spades, as far as I’m concerned.

How did you and Nels Cline first connect? And what do you value most about his playing? —Lane Delgado

When Sonic Youth first started going to L.A. in the early Eighties, Nels was working in this local record store that we always went to—Rhino Records on Westwood Blvd. That was right near Kim’s house [Sonic Youth bassist Kim Gordon], so we’d always end up there. And that’s how we first met Nels.

We knew he was a guitar player, and over the years we just struck up a long friendship. He was kind of a secret weapon around L.A. for a long time before he first got into the international scene, around the same time he started playing with Wilco. But we knew he was a fantastic guitar player from the earliest days we were going out to L.A. We’d go to see different shows he was doing—small club shows. We knew we had the same tastes and interests. We’ve been tight buddies for a long time.

What do I value most about his playing? He’s a monster player and he can play so many different styles. He can play snarling rock leads, or he can play tasty, beautiful almost pedal steel type stuff. He’s really a great colorist, and that’s one of the things I really love about asking him to play on my records. And he’s very sensitive to the material. He’s not just playing across it scattershot style. He’s really digging in and finding ways to enter it, even if he hasn’t been living with it for the past four months like I have when he comes in.

Was it your work with Glenn Branca’s guitar orchestra in the late Seventies that first got you interested in alternate tunings? Or did you do it before that? —Brandon Kingston

It was long before that, actually. When I first learned guitar—when I was 14 or 15—I had an older cousin who showed me some stuff. And he was into all these tunings. He was showing me tunings that people like David Crosby or Neil Young used—like dropped D and open D tunings.

Then when I was in college, I started finding out about Lou Reed in the Velvet Underground using the ostrich tunings—tuning the guitars to all one note and things like that, which seemed very interesting.

And when I moved to New York and started working with Glenn and Rys Chatham, they were doing all that stuff too. Actually, Glenn was really getting sophisticated about spreading his tunings across the frequency range. When I was in grade school and high school, I did a lot of chorale singing. And the chorus would be tenor, bass and alto and soprano.

And when I first started working with Glenn, that’s how he was referring to his tunings—the soprano guitar and the alto and tenor guitar. So it was very interesting to see how he was taking his cues from that kind of orchestral arrangement of either voices or instruments.

Then, when Sonic Youth first started, we didn’t have a lot of good guitars. Some of them were cheap and wouldn’t hold a normal tuning at all. So, taking a cue from Glenn, we started putting some of them in alternate or open tunings, and they became more useful as sound-making devices.

Ranaldo in Barcelona last year (photo: Alex Rademakers)

What’s your favorite Sonic Youth album? —Dwayne Evans

I don’t really have one. I helped make them all, and we never released a record that we didn’t believe in 100 percent. So my experience of those records is so different from everyone else’s. But I guess I like A Thousand Leaves [1998] a lot. It was the first record we made after we set up a serious multitrack studio, actually with the gear we bought on Lollapalooza [in 1995]. We bought a 16-track tape machine, a Neve desk and all that stuff.

We were just in our glory being in a recording studio all our own without any clock ticking, and just working away. I love the way we recorded that album. I love the way it sounds. I love a lot of that music. I love the title. That’s a favorite, I suppose, for me.

The other favorite is the last one we did. Which was an instrumental album on our SYR label, it’s SYR number 9, and it’s a soundtrack for a French film called Simon Warner a Disparu. It’s really beautiful music. But it’s kind of under-the-radar. I don’t know if it’s on the top of anybody’s album list.

What’s some of the coolest new gear in your arsenal? —Kit Palmer

I have a guitar built for me by this company in Germany called Deimel. Frank Deimel sent me a couple of guitars. There’s one he built me called the Firestar, which is a really cool guitar that I’ve used live a lot over the years. And I have a guitar made by this company out in Des Moines called BilT.

It’s kind of based on a Jazzmaster shape and it’s got wide-range humbuckers by Lollar. My electrics are usually set up with vintage Fender wide-range pickups or Lollars or Curtis Novak’s pickups. I’ve got a lot of guitars set up like that these days.

But I’ve really been focused on acoustic guitars a lot recently, both in my live shows and in the studio. So I’m trying to beef up my acoustic collection. Since finishing the Electric Trim album, I got two new acoustics by a maker I really love, Michael Gurian.

He was in New York in the early Seventies, and he trained all these guys who founded Froggy Bottom and all those boutique companies that are out today. Gurian was a classical guitar builder who later went on to steel strings as well, and he made these beautiful guitars for about 20 years.

So I bought one—all mahogany with a spruce top. I just completely fucking love this guitar. And it was built like a mile from where I live. In 10 minutes, I can walk to where Gurian’s first shop on Grand Street was, here in New York. At some point I got curious about what his rosewood models sound like, so I bought one of those too. This guy’s guitars are amazingly well-made, and they have their own sound. they don’t sound like Martins or Gibsons. He was really an innovator in a lot of ways.

Who are your all-time guitar heroes? —Anthony Garcia

That’s a hard one to answer! If it had to be just one, and I had to answer right this minute, I would say Joni Mitchell. I’ve hardly ever even tried to figure out how to play her songs, because they’re so complex. But I’ve been inspired by them a lot in terms of the acoustic guitar tunings and songwriting I’m doing now.

But a list of guitar heroes would include Jerry Garcia, John Fahey, all three guitar-playing Beatles, Keith Richards, Django Reinhardt, Robert Fripp… Some would be on my list just because they’re amazing tunesmiths. Paul McCartney is an amazing lead player in his own right, but he’s also a chord guy. Same with Elvis Costello. And there’s a young woman named Haley Fohr who performs as Circuit des Yeux. She’s working with a very unique vocal style and open tunings.

Do you think there will ever be a Sonic Youth reunion? —Ira Goldman

It’s really wise for me to never say never. But, honestly, I don’t ever think about it. And I really don’t think anybody else in the band is thinking about it. We’re all pretty happy and excited doing what we do now. I think the least interesting thing about it happening, for me, would be if it was just a nostalgia trip and we were playing our old material live.

The way I think Sonic Youth would go about a reunion would be to start with new music—seeing if there was anything worth pursuing there, in this current moment. It would have to be something worthwhile, other than just a ka-ching, dollar-making nostalgia machine. That’s never been Sonic Youth’s modus operandi.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

“Even the thought that Clapton might have seen a few seconds of my video feels surreal. But I’m truly honored”: Eric Clapton names Japanese neo-soul guitarist as one to watch

“You better be ready to prove it’s something you can do”: Giacomo Turra got exposed – but real guitar virtuosos are being wrongly accused of fakery, too