Nobody has ever described Dream Theater as minimalists, but even by the band’s own “bigger, grander, more of everything” standards, their 2016 album, The Astonishing, was the musical equivalent of two kitchen sinks and then some. A two-hour-plus double-CD concept piece spread across 34 songs, one that the band performed with an elaborate stage show from top to bottom for more than two years, it was every inch The Lord of the Rings of epic progressive rock. And like every good post-apocalyptic dystopian fantasy, it even spawned a book and a video game.

“The Astonishing lived up to its name,” says guitarist John Petrucci, who collaborated on the album’s music with keyboardist Jordan Rudess. “It was a big idea that turned into an even bigger presentation, and we saw it through on all levels.” Yet even before the album’s exhaustive tour ended, Petrucci was itching to do something new, and he weighed his options. “I had to ask myself certain questions,” he says. “How do you follow something like The Astonishing? You can either try and top it, which I didn’t want to attempt, or you do something totally different. Almost from the start, the latter approach seemed like the way to go.”

Ever since the 2010 departure of drummer-lyricist and band co-founder Mike Portnoy, Petrucci has been the prime mover and de facto captain of Dream Theater. He prides himself on running a smooth, harmonious ship, but he admits there were some grumblings from the other members — singer James LaBrie, bassist John Myung and drummer Mike Mangini — during the recording of The Astonishing. “Everybody prefers to be a part of the creation from the beginning, so there were a few complaints about how Jordan and I did that record. He and I wrote everything, demoed it, and we basically put it in front of the rest of the band. They didn’t really have a chance to participate in any other way.

They were gracious in accepting it, but I know they didn’t want to make another record that same way.” With that in mind, early in 2018 the band headed to the country to write their new album, Distance Over Time, at the secluded, five-acre Yonderbarn studios in Monticello, New York. The idea was for the band to compose together, with each member participating equally. “Nobody came in empty-handed, but nobody had full songs or demos, either,” Petrucci says. “What we had were snippets of ideas that we compiled at soundchecks and things like that. I had things I’d recorded on tour into my iPhone — riffs, chord progressions. Some of them were just 30 seconds long. So over a period of a few months, we played one another things we had, and we jammed.”

At first, the group hadn’t intended to lay down finished tracks at Yonderbarn, but they enjoyed the “summer camp” vibe so much that they decided to bring in some of their own recording gear and finish the project there. “When you work at other studios, there are all kinds of distractions,” Petrucci says. “People are dealing with their home lives; they have things to do and places to go. The whole Yonderbarn experience was so conducive to creativity. There was this big forest right outside our windows. We played music by day, and at night we’d have some drinks and BBQ. And we loved the songs we were coming up with. We were like, ‘It makes no sense to leave. Let’s not break the spirit’.”

Despite the lush, pastoral setting in which it was made, Distance Over Time packs a serious wallop. In many ways, it’s a photo-negative response to The Astonishing, clocking in at under an hour and containing some of the shortest, tightest tracks of the band’s career (no song exceeds the 10-minute mark). The album breaks out of the gate with the aptly named “Untethered Angel,” which features a blinding call-and-response passage between Petrucci and Rudess, and gathers steam with each successive cut. One might assume that after 13 albums, Petrucci might be hard pressed for new ways to spin an opening riff, but high-intensity doozies like “Paralyzed,” “Fall into the Light” and “Room 137” are fueled by some of the guitarist’s nastiest and hookiest guitar figures yet.

As always, his solos are mini-masterclass guitar clinics, each one causing a gobsmacked listener to ask, “How does he do that?” But that’s not to suggest that Petrucci is a cold technician. On the harrowing “At Wit’s End,” which concerns battered women suffering from PTSD, the guitarist unleashes a chaotic, nightmarish lead that perfectly underscores the song’s somber subject matter. For the most part, the band seems locked on “stun” throughout, only coming up for air on the gripping symphonic ballad “Out of Reach,” on which Petrucci provides a highly emotive (and decidedly Gilmour-esque) legato solo that seems to dance about like a butterfly before darting off into the air.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“To me, the album really shows that we still love what we do,” the guitarist says. “At the core of what we are as Dream Theater, if you take everything away — all the albums, tours, productions, stories, what have you — we’re still five guys who love to hang out and play together. That experience you have when you’re younger — you get together with your friends, you go down to the basement, crack open some beers and play — it’s right there in these tracks. Even at our ages, we haven’t forgotten why we do this.”

Your fans will undoubtedly pick their favorite guitar bits on the new album, but which moment do you just love to listen to?

[Laughs] That’s such a hard question! Wow, let me think… There are different moments that kind of scratch certain itches. On “S2N” there’s a fun breakdown with an extended guitar solo. I kind of like how it’s stripped down to the bass and drums, and I’m able to just build an improvised solo. By the time it’s done I’m this frenzy of notes. That kind of thing happens live all the time. I think that’s my favorite bit right now.

You’re pretty much the dominant force in the band. But is there a downside to that? Does it ever get to be a little too much, like, “Oh man, I’m shouldering too much here”?

Not really. It’s sort of self-inflicted punishment. [Laughs] I wouldn’t do it if I didn’t enjoy it. We could hire outside producers if we wanted, but there’s something so satisfying with seeing a record through from the initial ideas to completion. And I love the trust that the band gives me. I like the workload. It inspires me and it’s what makes me thrive. It’s a lot of work, but I welcome it every time.

But does it sometimes take you away from that thing you like to do — playing the guitar?

There is a balance I try to strike, and I’m not always successful at it. There’s a ton of work involved with recording an album, and sometimes I’m sitting at my computer, or I’m doing other stuff in the recording process, and I look over at my guitar and think, “It looks so lonely there… ” I sometimes don’t get as much time as I’d like to play, but everything else I do is so satisfying.

Before you go in to record an album, do you increase your practice routine to get your chops in tip-top shape?

It’s not crucial at the beginning because you’re kind of easing into it; you’re getting together and you’re playing. When you make a record, you want to be at the top of your game — you want to push boundaries and do things you’ve never done before. So you have to be in the right headspace for that. Fortunately, being up in that barn in Monticello, feeling very peaceful and with no distractions, I felt really good.

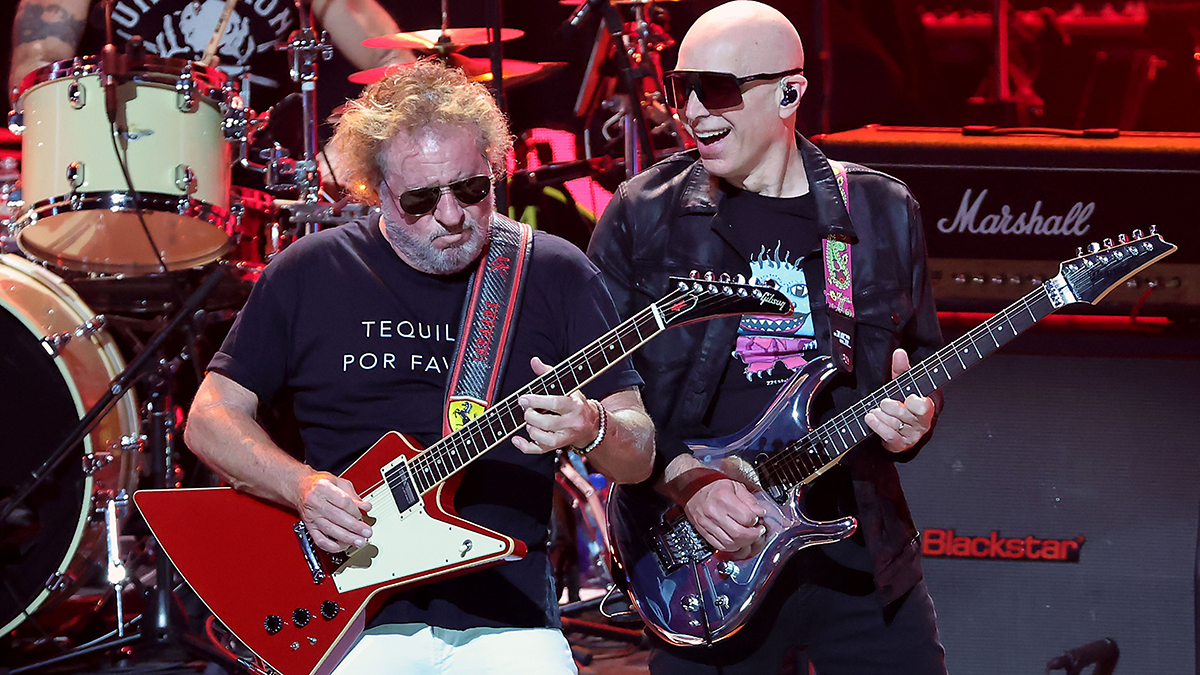

Another thing that helped was the fact that I’d just come off the G3 tour. I did two legs, so that was something like 80 shows. We’re talking four months of guitar, guitar, guitar. My chops were totally together. There was no way I wouldn’t be in shape! [Laughs] Oh, and I also did my guitar camp — it was timed right before I started my guitar solos. So I was surrounded by all of this unbelievable talent — Al Di Meola, Guthrie Govan, Tosin Abasi, Jason Richardson, Andy James, Rusty Cooley, Tony MacAlpine — just an insane guitar community. Being around them and playing with them kept my chops way up.

The idea of everybody throwing ideas around sounds great, but did it ever become a free-for-all? Were there times when you had to “herd the cats”?

[Laughs] That’s funny. Actually, there’s never any need for that. We’ve known one another so long and play so well together, so we kind of know how to anticipate what the other guy is going to do. Sometimes there are debates about certain sections, but we never have crazy differences of opinion or impasses. I do wear the producer’s hat, so if we get stuck and a decision has to be made, I’m able to do that in a diplomatic way. The vibe was just so conducive to what we were doing, and because we weren’t in a commercial studio, we could do whatever we wanted. We could play, hang out, have lunch, do some BBQ, have some drinks — we didn’t have to worry about anything other than making music. It really helped to get rid of as many outside distractions as we could.

Describe for me the setup for how you recorded. Where were you in relation to the other guys while tracking?

The barn is this big, beautiful structure with 30-foot ceilings in the main room. That’s where we had all the gear set up to write in. Once we decided to just record the album there instead of moving to another studio, we had to build out what was missing. All of the wiring and everything was all set — all of the tie lines and everything. We just had to bring in mic pre’s, microphones, a desk, computers, speakers, all of that. We own a lot of that stuff, so we used it to sort of return the place to an operating recording studio. There was basically a control room upstairs that overlooked the big main room, and I was pretty much in there when I tracked guitars. My gear was on the main floor, so I was in the guitar room with the engineer, and I could look down into the main room isolated from the guitar amps that I was cranking beneath me.

Let’s get into some of the songs. That insane call-and-response between you and Jordan in “Untethered Angel” — how long does it take for you guys to work that out?

When we’re writing a song, we bake that into the cake. We know that a particular section is going to be a back-and-forth part, so when we record the demo we’re improvising and putting down placeholders. Later on, when we’re actually tracking, that’s when we’ll go in and lay down the final parts. It doesn’t take as long as you might think. When we’re jamming, we’ll tell the other guys, “Give Jordan and me half an hour to work out some stuff.” Sometimes we’ll play a really cool part when we’re messing around and we’ll want to keep it; other times, it’s just a vibe for what we want. We usually don’t fully compose the sections out until we’re tracking.

The riff for “Fall Into the Light” is startling coming from you. It’s very much early Led Zeppelin. When you whipped that out, did everybody say, “Fuck yeah!”?

Absolutely. I came up with that stuff when I was on the G3 tour. I had my signature Boogie head backstage and I was dialing in some sounds, and I got this perfect tone. Right there, I played the riff and recorded it into my phone. I could tell that it had something to it. Later on, when we were writing, I said, “Hey guys, I think I have a cool riff here… ” When they heard it, they were like, “Oh, yeah!” [Laughs] It’s very blues based; it has a Zeppelin/Metallica thing. It’s fun to infuse that style into what we do — something fun, mean and powerful.

Speaking of bluesy, there’s “Room 137.” The song itself isn’t blues, but there are moments in the solo that sound like Billy Gibbons could have played them. They’re snarky.

Definitely! Yeah, that’s a good way of putting it. That song has a bit of a heavy swing feel, which is not something that we’re known for. That stuff comes out of jamming. We do blues jams, Latin jams, swing jams — stuff we don’t normally put on our records. They’re fun ways to approach soundchecks. So that’s how “Room 137” came about. That Billy Gibbons thing in the solo is funny because it’s a little lick I learned from Joe Satriani. He would play this thing every night that got sort of a harmonica sound. I asked him, “How do you do that? Every time I try it, it doesn’t sound right.” He showed me the technique, and do we would do it on the G3 tour — every two bars I would throw it in, and we would crack up. It got to be overkill. But that sort of influence felt perfect for that solo with the swing feel. It’s a little bit bluesy, a little rock ‘n’ roll — it’s cool.

In the solo for “Barstool Warrior,” you stay pretty close to the chorus melody. Are there songs in which you feel that’s more appropriate than others?

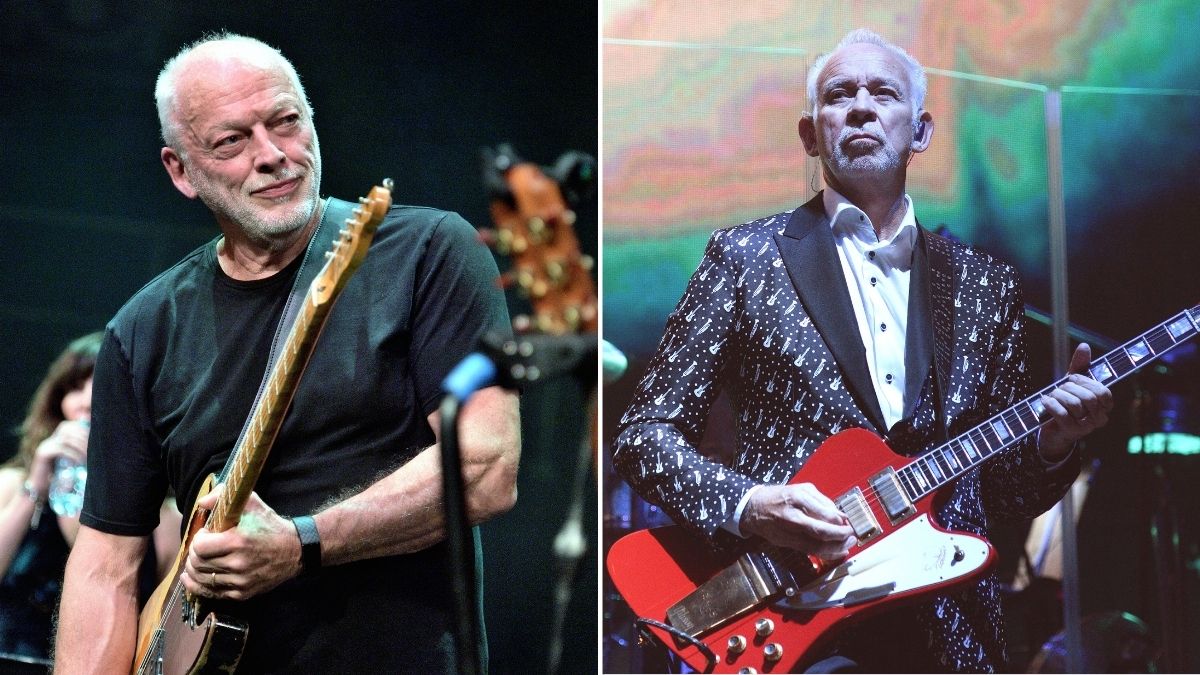

Sometimes, yes; other times, not as much. A lot of times the vocal and instrumental melodies that are embedded within the chorus all happen simultaneously when we’re writing. So I kind of know what melody or theme I need to call upon when I’m starting a solo. Again, it’s baked into the cake. I’ll play a bit of the chorus as a starting point, and then I’ll pull out the shred and go off. That starting point is always a lot of fun — the singing, crying kind of style. I’m influenced by Gary Moore, Joe Satriani, Neal Schon and, of course, David Gilmour.

Your solos for “Out of Reach” and “Paralyzed” are very Gilmour.

That’s interesting. As much as I love Gilmour, I hadn’t thought of him in those ones. The solo in “Paralyzed” is played on a baritone guitar, so it’s a little bit tougher to play because of its fatter strings and everything. That’s another example where I was really trying to state a strong melody at the start.

The subject matter to “At Wit’s End” is heart-wrenching stuff. Did you approach the solo to match the song’s lyrics?

It’s not exactly a yes or a no because sometimes we know the subject matter of a song when we’re writing the music, but sometimes we don’t. In this case, we didn’t know the lyrics James was writing, but I think the music sort of influenced him. So that’s why there’s a bit of a gray area there. With that song, I was responding to what we were jamming on, and there was definitely an aggressive or chaotic feel to the music. As a guitar player, it’s something you just instinctively know how to do. The solo felt appropriate to the big picture, and I think James responded in his way.

From a guitar standpoint, was there any one song that gave you a particular fight while recording? Something you really had to labor over…

There wasn’t really any song that gave me a fight, and I think it’s because of how we wrote and recorded. We rocked out on every song before we put it down, so by that time everything felt great. If there were any sections that required more concentration than others — “Pale Blue Dot” had some wacky, super-fast things — I kind of smoothed them out before we recorded the keepers.

Let me ask you about the guitars you used. Were they primarily your signature Ernie Ball Music Man Majesty models?

Absolutely. I used my Ernie Ball Music Man Majesty on all of the songs except for two. The Majesty is the ultimate guitar for me, and it’s 100 percent in my comfort zone. On “Paralyzed” and “Out of Reach,” which are tuned to B-flat, that’s my signature BFR baritone Ernie Ball Music Man. There’s a bunch of different tunings, and a lot of seven-string guitars. “At Wit’s End” is tuned a whole step down to D. “Untethered Angel” is two whole steps down to C. I love different tunings — they’re fun to play with, and they make for a diverse sound overall. There’s also a little bit of Taylor acoustic. The company sent me a brand-new one with a really cool bracing system [V-Class bracing]. It sounded really nice, but I can’t remember the exact name of the model.

How about your amps?

It was all through my signature Mesa/Boogie JP-2C head. That’s the basic sound — the guitar into the head and into a Boogie Recto 4 by 12 cabinet. There’s no reason to bring in anything else.

Any new effects?

I generally don’t use a lot of effects when I record, so if I’m looking for a front-end phase or chorus, I’ll go right to my TC Electronic pedals. You hear that every once in a while. I did get a new toy I’m using a lot, the 2290 plugin. I use it on “Room 137” — it’s right in the mix. It sounds exactly like the original 2290. I also used my signature Dunlop JP9 wah. It’s exactly what I want to hear — that aggressive, deep, throaty sound.

I can’t believe you just said “deep throaty.”

[Laughs] Oh, my God. Did I say that? Can that be printed?

I could always add a comma — “deep, throaty.”

There you go. [Chuckles] Whew!

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.