At a time when many artists are calling into question the validity of the album format, Jimmie Vaughan remains a staunch advocate of long-form recordings.

“I still love albums,” the veteran blues guitarist states. “I know there are changes in the way records are being delivered, but that’s just progress. Albums are still important, and I don’t see that changing. You give me a well-played, well-recorded album, and it’s like I’ve got a new friend. I’ll listen to that thing forever.”

Even so, Vaughan admits the process of recording albums can be stressful and exhausting, but he’s come up with a workaround to keep the experience fresh.

I just pretend we’re cutting some 45s. So I’ll do two songs, maybe three, and then we’ll take a break

“I just pretend we’re cutting some 45s,” he says. “That’s how they did them in the old days - you go in and cut a couple of tunes, and everybody has a great time. So I’ll do two songs, maybe three, and then we’ll take a break.

“I do that every few weeks, and that cuts down on the stress factor. I’ve sat in studios for weeks and weeks, and I’ve seen spirits drag. Keep it short, keep it fun - in the end you’ll have a great album.”

Which is more or less how Vaughan went about recording his new album, Baby, Please Come Home, working with members of his long-standing 'A team' (drummer George Rains, guitarist Billy Pitman, bassist Ronnie James, keyboardist Mike Flanigan, and sax players Doug James and Greg Piccolo, among others) for concentrated, two-and-three-song sessions at the Fire Station Studio in San Marcos, Texas, over the past year.

The disc is the third in what has now become an anthology series that Vaughan began with 2010’s Plays Blues, Ballads & Favorites and followed with 2011’s Jimmie Vaughan Plays More Blues, Ballads & Favorites on which the guitarist (who handles the lion’s share of vocals but sometimes steps back and lets guests Georgia Bramhall and Emily Gimble take over) digs deep to uncover rare gems from artists that he holds dear.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The new set features fiery renditions of little-known tracks once recorded by the likes of Lloyd Price, Jimmy Donley, Lefty Frizzell, T-Bone Walker, Bill Doggett and Jimmy Reed, the latter of whom has been a particular source of fascination for Vaughan, who in 2007 teamed with singer Omar Kent Dykes for a full-album reading of the late bluesman’s work called On the Jimmy Reed Highway.

“I love all these artists and the songs they did,” Vaughan says, “but you take a guy like Jimmy Reed, and you’re talking about one of my main inspirations. He’s like the cornerstone for me. His stuff belongs in the Great American Songbook.”

Fans of Vaughan’s distinctive guitar work will find that Baby, Please Come Home offers an embarrassment of riches: On every track, he peels off memorable, punchy and tasteful leads characterized by his instantly recognizable crystal-clear tone. But the album also demonstrates Vaughan’s growing strength as a vocalist, a talent he’s become more comfortable in exploring.

“I was a little shy about singing in the past, but as time goes by I think I’ve found my lane,” he admits.

“There were a couple of songs I wanted to try on this album, but I thought that the vocal acrobatics might be a little out of my range. So I listened to the tracks and said, ‘OK, I could do my own version of this,’ and I put my own little spin on it. The bottom line was, ‘Can I have fun with this and do the material justice?’ All things considered, I think we pulled it off.”

In your early days, how did you go about developing your own style of guitar playing?

"In the beginning, everything was a mystery to me. The main thing I worked on was getting from point A to point B. How do these people that I’m listening to know what they’re going to play?

I started to imagine myself in a room with my favorite guitar players. In my mind we’d be doing a roundy roundy, and when it got to me I had to play something. 'OK, now what?'

"If you listen to San-Ho-Zay by Freddie King, after he gets through the head, how does he know what to do next? That was one of the questions I asked myself early on, and it became my mission to figure that out. So what I did was, I started to imagine myself in a room with my favorite guitar players. In my mind we’d be doing a roundy roundy, and when it got to me I had to play something. 'OK, now what?' I’d be thinking. Eventually, my brain and my heart gave me that answer."

Sounds like you were really trying to figure out improvisation.

"That’s what I’m talking about. You may have a vocal tune, but when it comes to the guitar solo, you have to improvise. The goal is to play what you feel, and so you have to ask yourself that. Once you figure that out, it all comes naturally."

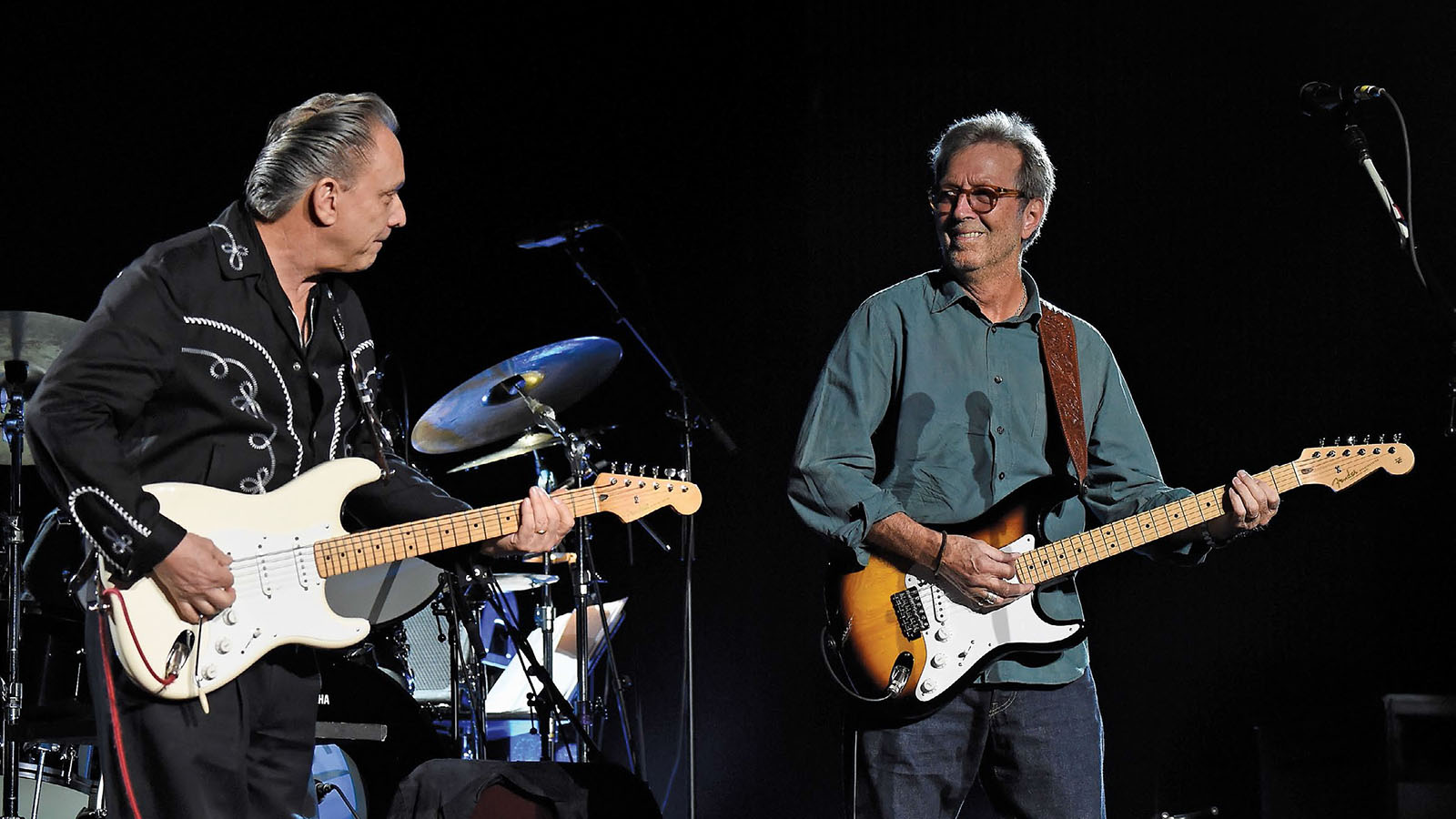

You used to imagine yourself in a room with your favorite players, but at a certain point in your life, you actually got to experience that. How different was the reality from the dream?

"Oh, it was crazy! [Laughs] When you play with BB King or Eric Clapton or Robert Cray, it’s like you’re trippin’. Later, when you get back home, you’re like, 'Oh, man, did that really happen?'

"It’s like you come out of a dream state or something. But when you’re in that moment, when you’re actually going toe to toe with these guys, you have to not let your shield go up. You have to just allow yourself to be free. And that’s hard to do, because guitar players get nerves just like anybody else."

Your tone is very distinctive; it’s clean, clear and percussive. When did you start crafting that?

"Right away. I listened to Magic Sam, Buddy Guy, Lonnie Mack and Freddie King - a ton of other guys, too. But what I noticed about them was, they not only had a certain way of playing, but they also sounded like themselves.

"It was their signature thing. So it’s a process. You start emulating the people you admire, but eventually you have to develop your own thing. Once you do that, you can’t do anything else, ’cause it’s yours."

When you and Stevie were teenagers, did you two discuss tone?

"Oh, of course! I’m four years older than Stevie, so I was the one with the electric guitar and amp; I had the record player and records. He would watch me learning how to play, and then when I put the guitar down, he would pick it up. He learned all the same lessons just by being around me."

I asked that question because his tone was sometimes very different from yours - more overdriven and dirty.

"It was different, but I don’t think it was completely different. If he ever got in a situation where there was a hot guitar player in the room, Stevie would start playing Hendrix licks. He knew nobody else could do that."

So that was Stevie’s way of shutting people down?

"Yes, but in the in the nicest way possible."

I’ve talked to a number of younger guitar players who cite you a mentor. Who mentored you back in the day?

I enjoy doing more obscure-type stuff. I could do a good job with Hide Away, but what’s the point? Freddie King did it, and so did 50 other people. Who cares if I do that one?

"Some of the people I mentioned already, but there were a couple of my uncles, too. They played guitar in country and western swing bands - they played Merle Travis and Chet Atkins and things like that. So I kind of absorbed all of that.

"If you listen to Merle Travis’s old records, and then you listen to Jimmy Reed or Hank Williams, you start to understand that it’s kind of the same thing. I just think of it as American music. Record companies and radio stations came up with the different categories, trying to sell it to different groups of people. But I heard that stuff early on from my uncles."

You and the Fabulous Thunderbirds were the house band at Antone’s in Austin. What do you think it was about that club that made it such a breeding ground for blues guitar players?

"It became our place to play. [Singer] Kim Wilson and I had a band, and we played the kind of music that we loved - Little Walter, Junior Wells, Buddy Guy. So it was half-harmonica, half-guitar. Clifford Antone came to us and said, 'We’re going to open a club called Antone’s, and we’re going to have nothing but blues. No country bands, no music from all these other categories - all blues. And I want you to be the house band.' We said, 'OK', because we knew this would be our guaranteed place to play.

"So we became the house band, and whenever Clifford would hire somebody to play - whether they were from Chicago, Mississippi, Tennessee, California or wherever - we had to learn how to back them up. That became our business. It was like we were in blues college."

How did you do actually go about selecting material for the new album? Did you just comb through your record collection and pick out cuts?

"Well, that’s really it. I listen to this music all the time, but I still make discoveries. There’s new artists and old tracks. I go to record stores and find them - I love going to record stores. And YouTube is fabulous. I’ll get on it to look at one thing, and before you know it I’ve found five songs I’ve never heard before. The internet is incredible, man."

Beyond your ability to sing a song, were there any tracks you didn’t want to touch because you considered the guitar playing on the original sacrosanct?

"There is a little of that, yes. I enjoy doing more obscure-type stuff. I could do a good job with Hide Away, but what’s the point? Freddie King did it, and so did 50 other people. Who cares if I do that one? So it’s not so much that something’s sacrosanct; it’s more like, 'Do I wanna do something you’ve heard a billion times?'"

Let me ask you about the title song, Baby, Please Come Home. It’s a really old song, written in 1919. Which version did you first hear?

"I heard Lloyd Price’s version. That’s the great thing about this stuff - you can trace a lot of this music to the beginnings of recordings. There’s some great versions of this song, but I like what Lloyd Price did.

"Now, when I listened to it, I thought, 'How can I make this my own song?' I took a lot of stuff out and put the guitar in there. If you listen to Lloyd Price, he shouts. I didn’t do that. I just played guitar."

In the solo of Just a Game, you play a sequence of notes, and then you kind of end it with a trill. It’s like a form of punctuation. Where does that come from?

"That’s a cool sound, isn’t it? I call that 'buzzing'. I don’t know where it comes from, but I just like it, so I do it. I guess it’s a trill, if you want to get technical. If you imagine dropping a BB off the stairs, and it goes 'bing-bing-bing-bing-bing' when it hits the bottom, that’s the sound I try to make. I guess it ends a phrase well. It’s a form of punctuation, sure."

No One to Talk to But the Blues is interesting. It’s by Lefty Frizzell, one of the pioneers of country, but it’s a straight-up blues song. Could you explain more?

"Absolutely! That’s exactly my point. Country guys and blues guys are the same. Record companies tried to put them into different bags, but that wasn’t coming from the artists.

"If you listen to Ray Price or Buddy Emmons or Little Milton or B.B. King, it’s all blues and jazz, and then you’ve got country in there, too. It all molds together in my book."

On Jimmy Reed’s Baby, What’s Wrong? there are moments in which you refer to his simple, one-string soloing. Did you consciously stick to parts that he played?

"I don’t know if I thought about it - it just came out that way. Listen, I’ve studied all his stuff because I dug it so much. I wanted to be like him. If I do some things like him, it’s because I revere him. He’s a hero of mine.

"I would tell a young person today, 'If you don’t listen to Jimmy Reed, you’re gonna miss out.' His music is so American. It’s like, you can put Hank Williams and Jimmy Reed together - in my book, they’re the same thing."

Which guitars did you use on this album?

"I used my new signature guitars that Fender made for me, my new model. These ones are made by the Custom Shop. The first version was made in Mexico, and they were 700 or 800 bucks. Really, the only difference is the materials.

"The new guitars that I have out from the Custom Shop are the best that they can do with the best materials they can get. We can sit around and argue about which one’s best - they’re both very good. But those are the ones I used on the album, the new models."

How about amps?

One day I imagined to myself, 'What if the world ended and there were no more guitar picks?' So that’s why I use hotel room keys for picks

"I used Fender Bassmans and a boutique amp made by John Grammatico. He does an amp called a Kingsville that’s like a classic Bassman. The Fenders are reissues. I love vintage amps, but there’s so much toil and stress finding them and worrying about them. With the reissues, you can just go out and buy one."

You’re not a big effects guy, right?

"Not too much. I like tremolo and some reverb. I use a Strymon [Flint] pedal that gives me both effects. That’s really all I bother with. Everything else is from the way I set up the amp and how I play."

Do you still cut up plastic hotel room keys and turn them into picks?

"I do. I cut them up to make the kind of point that I like. I travel so much, so I’ve always got hotel room keys. One day I imagined to myself, 'What if the world ended and there were no more guitar picks?' So that’s why I use hotel room keys."

Of course, if the world ended, there wouldn’t be hotels.

"Yeah, that could be a problem, but we’ll worry about that when we get there."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“Damn, that guy could shred. Can you imagine what that would have sounded like?” Wednesday 13 says the late Alexi Laiho once came close to joining him and Slipknot’s Joey Jordison in Murderdolls

“I left without a penny to my name. I was bitter for a while, but I’ve got a great legacy”: Though Pete Quaife gets credit for jumpstarting the Kinks bass chair, John Dalton and Jim Rodford pushed the band forward on many of their classic albums