Jethro Tull Six-String Legend Martin Barre Chats About His New Album, 'Roads Less Travelled'

"I wanted to make an album that reflected everything I like about music and playing the guitar."

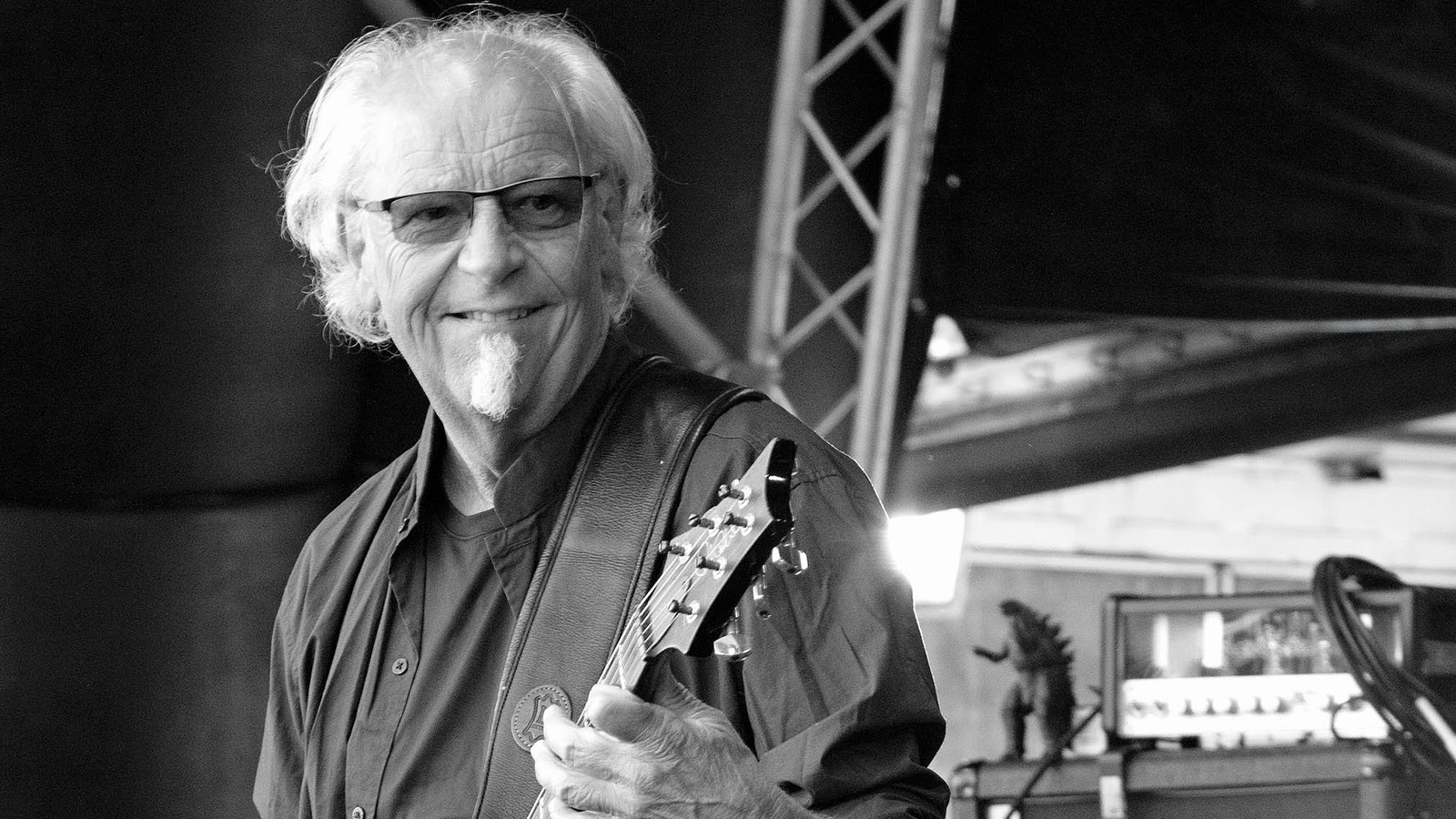

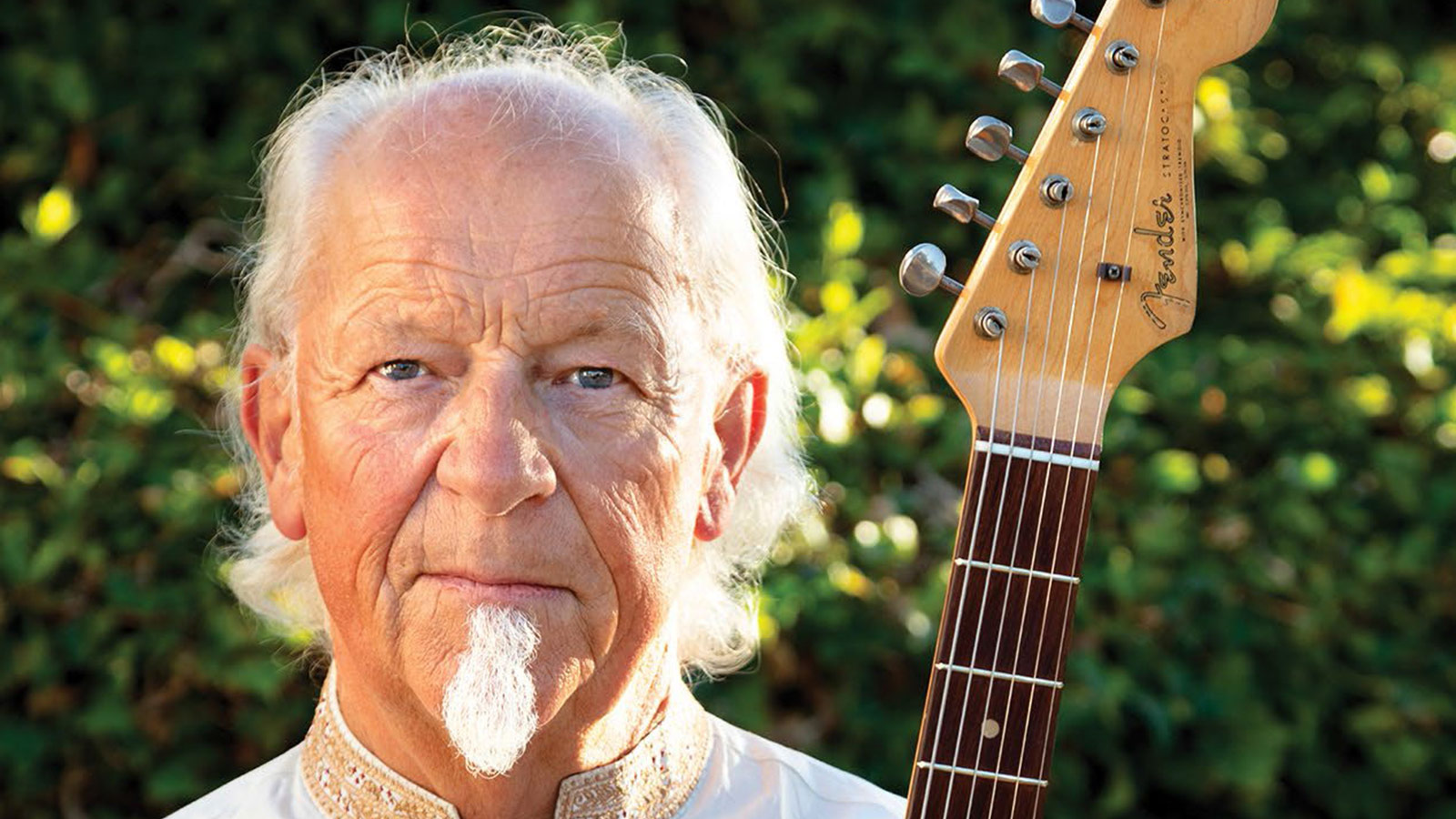

Martin Barre, one of the most influential names in prog-rock guitar for almost 50 years, is most closely associated with giants of the genre, Jethro Tull. His first recorded appearance with the band was on their second album, 1969’s Stand Up, which saw them morphing from a fairly conventional blues-rock outfit on first album, This Was, into cross-pollinations of jazz and rock, with a uniquely English sensibility that continued to develop from album to album. Tull constantly pushed boundaries, incorporating folk and medieval elements into their blues mould to create a sound distinctly their own.

Since Tull effectively ceased to function as a unit in 2011 beyond “Ian Anderson plus,” Barre has been carving out a highly successful solo career, leading a crack band of likeminded souls into a series of albums and live sets; the likes of which include often radical reworkings of Tull classics sitting comfortably next to Barre’s originals and even a handful of covers, among which his take on the Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby” has been a highlight. With his smoothly singing, sweetly distorted signature tone and his always unpredictable note selection, his solos and fills never take the expected route. Indeed the title of his new album, Roads Less Travelled, would make an ideal description for his own unique approach. Extremely self-effacing, with a great memory for the details of his lengthy career, Martin is an interviewer’s dream.

To reel back to the very start, I believe that when you began to play in 1960, your dad gave you albums by jazz guitarists such as Barney Kessell, Kenny Burrell and Wes Montgomery. Was he a big jazz fan?

My dad was from a French family and his father was an orchestra leader in Paris, playing the violin. My dad wanted to be a clarinettist, but things got in the way and he had to work in a factory. When I left university to go professional, most parents wouldn’t have been too pleased, but he never said anything, and I realized later that it was because I was doing something he’d have really liked to have done. He was very supportive.

You were starting out at a pretty sophisticated level, rather than the standard U.K. guitarist influences of the time, such as Hank Marvin of the Shadows.

Ha, ha. No! I was only listening to it. I didn’t like jazz at all. I did like the flute. I liked Frank Wess and Roland Kirk, which is why I started to learn the flute at 15. You’ve hit the nail on the head, though. It was Hank Marvin who lit the fire for me, like so many young kids in England. He inspired everybody to play in a band. But we were so hungry for music that the Shadows and Cliff Richard were never going to be enough. Every time an album came into the local record store from Gene Vincent or Eddie Cochran we’d play them until they wore out.

The album sleeves themselves — with the iconic guitars that you could never find in England in the early Sixties — were so important.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Yes. I used to look at the pictures and dream of those guitars! I dreamt of a career in music too. Over a period of years it took over everything else until I got kicked out of university. I was gigging six nights a week at that time! I was stupid enough to think I could be a professional musician and moved to London.

Well, it worked out well.

It didn’t at first. The only job I could get as a professional was to play saxophone in a soul band. I literally picked up the sax and learnt how to play from scratch to join a band — my flute skills were helpful there — and that band stayed together for three years then morphed into a blues band, as that became fashionable on the U.K. music scene toward the end of the Sixties.

When you were first starting out, did you go down the infamous Bert Weedon Play in a Day book route that so many legendary U.K. rock guitarists started with?

Never did it for me. I had one lesson with a local guitar player. He was so out of touch with what local kids were listening to. He didn’t connect at all. There was no sense of “what do you want to learn?” So I thought “No, thanks” and moved on. It made me use my ears as there was no other information available out there. I bought records and then just labored over learning the guitar parts by playing the record over and over by trial and error.

It’s so different now. You have guitar tabs, YouTube, apps — there’s so much out there to accelerate your development.

It’s not fool-proof, though. My daughter’s partner is learning. He’ll pick up things from YouTube, then when I’m visiting show me what he’s been working on, and I’ll be saying, “No. Not like that! I’ll show you a better way.” But that’s also experience. Essentially, playing the guitar, you need to mold it around your personality. It’s not an overnight thing. It’s all the years of practice and experimentation and finding your own style and sound. You can’t shortcut all that.

You see all these guys on the internet. I call them “technique monkeys.” They can play awesome reproductions of Yngwie Malmsteen, Eddie Van Halen, and the like, but there’s nothing of their own there, no unique personality.

Exactly. You could give them a simple 12-bar blues and they’d be lost because they’ve got no grounding. They’ve learnt skills without application or purpose. There’s no invention from their own minds; No learning curve, no voyage of discovery.

Upon joining Jethro Tull, you were stepping into the Mick Abrahams role. Maybe not quite as hard as replacing Eric Clapton in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, but still a big pair of shoes to fill from the fans’ point of view. Did you have any anxieties about the pressure?

I did at first. I was a nervous kind of guy, and I had huge respect for Mick. The fact that the music Tull was playing changed [after the release of the first album] meant that I wasn’t playing the same sort of music. But the fans in ’68 wanted a blues band. They didn’t like what we were doing, playing the music that became our second album, Stand Up. They slowly came around to it. They’d sort of stare at me with that look, kind of “Come on, what have you got?” And I’m thinking, “I don’t know!”

I’ve always been a person that will throw themselves into a situation where something needs to happen, though. Almost like an adrenaline junkie, out of my comfort zone.

Tull were already a successful band when you joined. As the decent money started coming in, did you get into that crazy vintage-guitar-acquisition mode?

No, it never happened like that. I had one guitar for a long time, and when I wanted a better guitar I sold the one I had. If you had two guitars it was like, “Why? Why do you need two? You can only play one!” You’d be offered Fifties Gibsons and Fenders for less than $200. It wasn’t the kind of silly money you see now for an old guitar. The main concern in those early days was to get more reliable equipment. Everything was so prone to breakdown. Amps were blowing up all the time.

Do you have a guitar that you’d grab in the event of fire?

No, because I own the guitars, the guitars don’t own me. The guitar I play most is a small collapsible travel guitar made in Switzerland. It’s not very valuable, but I pick it up every day. It’s a lovely instrument to play. I’ve had valuable instruments that I’ve sold or that I’ve even re-bought. The money becomes a means to an end. If I’m financing a tour and I want the two girls on onstage, I’ll sell a vintage guitar.

You often say that in Tull if you didn’t get the solo on the first or second take it would end up being a flute solo. Was it actually that cut-throat?

It was like that. If you go back to when you were working on eight- or 16-track recorders, you didn’t have the tracks spare to put on extra solos. I don’t particularly like that approach. When I record now, if I don’t get it on a couple of takes I want to stop. I want to erase and start again. When I listen to the solos on the early Tull albums, the playing leaves a little bit to be desired, if I may say so.

I think that’s probably more your hindsight than a fan’s listening perspective.

Maybe. I see the faults in what I do. The way I record now the faults disappear. I like spontaneity, though. The best performance will always be in the first two or three attempts.

As soon as you left Tull — if you want to call it “leaving” and not a hiatus — did you feel worried about the pressure to be the man it all hangs on, or was it a sense of liberation and empowerment?

Tull became a comfort zone. The same tours, venues and songs. Once you become comfortable, things become sterile and stagnant. You’re not progressing. It was a shock, because I didn’t see it coming, but now I think it’s the best thing that ever happened. I’m not somebody who’s going to lie down easily. I’ve got a strong will, I’m determined and stubborn and it made me get my act together. It liberated me as a guitar player. It made me realize how unadventurous I’d become. I got involved with all of the processes of getting a band together. It made me play a lot more guitar on the songs, plus I was talking to the audiences, communicating with them. I’m a much more complete person and musician than I ever was.

Would you feel too restricted to return to Tull as a regular jobbing band member?

It’s not in my universe now; it happened too many years ago. I’ve got a great band now, and that’s my band. I don’t want to play with another band. Next year I’ve got a tour planned called Stand Up America. It’s the beginning of a 50th celebration with Clive Bunker and Jonathan Noyce. I’ll have the girl singers; there’ll be nine musicians on stage, and we’re going to play Tull music, do a double CD, celebrate everything I’ve been through musically with Jethro Tull.

It’s obvious from so much of your solo work that the distinctive sound of Jethro Tull owes at least as much to your contributions as Ian Anderson’s. Does it leave any lingering frustration that Ian’s role as frontman often seems to overshadow other contributions?

I did my job as a guitar player. I wrote my own parts, my own inventions. Guitarists have a big role in a band. Ian was the frontman, the guy who sold the image, the brand. He did it really well. He was the focus, the kind of PR part of Tull. We all had a job to do. The real unsung heroes were John Glascock, Barrie Barlow and John Evan. I’ve had a lot of recognition.

I’ve seen reports of your new album being something of a blues-type affair, although having listened to it a few times I’d say it’s not blues in the sense of 12-bar workouts. There’s a level of sophistication in the riffs and melodies, and the solos go way beyond the predictable pentatonic box-position-type thing. It’s much more varied than a straight blues album.

Yeah. I don’t have an agenda. I don’t have to do a blues or jazz or prog album. I’m not fettered by a musical style. I’ll often listen to an album by a new guitar player and be quite disappointed by how narrow their depth of field is. I want to be able to play mandolin, write the songs, get acknowledgement for writing all the vocal harmonies. It doesn’t need to be in your face. I hope people can hear the subtleties.

The new album has an interesting mix of male and female vocals. The tracks with the female vocals have a very contemporary sound. It wouldn’t be a stretch to put a hip-hop beat under them for a kind of gritty, urban feel.

Yeah, I want people to be surprised. To dedicate a track to a female vocal is a great left turn. I want to play everything that I like. The diversity — mandolin, acoustic slide guitar — you know?

The opening riff on “This Is My Driving Song” has a Zeppelin- type “Black Dog” groove underpinning it, but there are acoustic interludes that suggest a hint of Elizabethan chamber music. Kind of almost a “Bluesabethan” vibe.

Ha, ha. Yeah! That’s a great song to play live for us as well. They are such a great band and they bring their own personality to the songs. When we’re recording I encourage everyone to come up with ideas. I would always prefer someone to try something totally off the wall that might not work than just play it safe.

Although this is a solo guitarist’s album, it’s all about great songs. There’s a ton of guitar on the album, but in subtle places — great fills or clever rhythmic motifs.

I wanted to make an album that reflected everything I like about music and playing the guitar: melodies, harmonies and no compromising of ideas to try to fit into whatever box might be expected of me.

These days your sound is PRS into Soldano with only a modest treble boost in between, a very minimalist approach.

Yeah, I’m not a gear nut. I learnt my lesson in 1967. I was in a studio doing a session for Eric Burdon and we were doing the backing track. Jeff Beck wandered in; we were in awe. When we finished the track he picked up an old amp and guitar in the corner of the studio, plugged in and sounded amazing. And it was Jeff Beck that produced that sound, not a particular amp or pedals. It was purely him. He was totally in control. He could’ve reproduced that anywhere in the world in any circumstances. That’s what I’m always aiming for.

You must be relieved to have been successful in an age where people paid for your music. In the age of the illegal download, do you think an artist can make a living anymore?

I’m not driven by money myself. Musically it’s an easy decision; I want to play music and if I can make enough to enable me to fund the next year or album, etc., that’s all I ask of it really. The finances do dictate what you can and can’t do with your music, but they don’t dictate the music you make. Every day you have to fight to survive in a very tough business where we’re all after the same thing.

I’m always struck by how vital and alive musicians are in their 60s and 70s. I always think it’s because rock and roll is the elixir of youth.

Exactly. I never feel any conversational or emotional or numerical gap with the younger guys I work with. I don’t acknowledge age. I think music is the elixir of youth!

• GUITARS LIVE: Various PRS Guitars models including 513, ME Quatro, McCarty Semi Solid, Customs. STUDIO: PRS Guitars models, Hamer sunburst, Gibson ES-335 (1961), Gibson ES-135 (1985), Gibson ES-235 (1956), Gibson F4 mandolin (1917), Gibson A5 mandolin (1958). ACOUSTIC (live and studio): Variety of Taylors, primarily a 12-fret 612 • AMPS Soldano Decatone, Soldano 25. Marshall 2x12 and 1x12 cabinets. STUDIO: Soldanos, Marshall Studio 15 and a variety of Fender amps • EFFECTS Alesis Picoverb in send/return (used for a modest amount of reverb)

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.