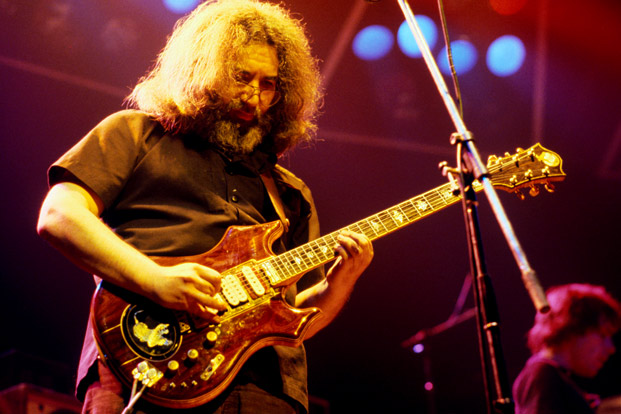

Grateful Dead's Jerry Garcia Talks Gear, His Near-Fatal Illness and 'In The Dark'

Here's an interview with the Grateful Dead's Jerry Garcia from the December 1987 issue of Guitar World, which features Joe Perry on the cover. The original story ran with the headline, "Back From the Dead: A little grey around the edges but still as out there as ever, Dead Head Jerry Garcia is pickin’ his way to prosperity."

Jerry Garcia looked around the Grateful Dead’s rehearsal studio in San Rafael, California, and smiled. “It’s good to not die,” said Garcia, who suffered a nearly fatal diabetic coma in July of ’86.

The legendary guitarist whose mercurial improvisations are the life’s blood of the Grateful Dead’s music has made a miraculous recovery from an illness that at first left him incapable of walking, speaking clearly or playing. “I remember the moment in the hospital when he was recuperating,” said Dead drummer Mickey Hart.

“Once he came out of his coma, you could see that he has life back in him,” The first thing he asked for was his acoustic guitar. He must play, he’s an animal. He’s like a thirsty animal, like a shark, always eating, always playing. If he can breathe, he’ll play.” Garcia insisted that he was never aware of being seriously ill. “For me it wasn’t one of those near-death experiences,” he explained.

“It was very weird, it had a sort of science-fiction quality to it. But it wasn’t painful, it was cerebral. The weird part of it was that it took a while for me to get to the point where I was understood. I had to fish for everything.

"It was like everything was in random access, I know all the words, but I can’t get it out of myself. So for the first few days it was mostly sort of Joycean inversions of language, and then after a while I started to remember how it worked. But I had to do that with everything. They had to teach me how to walk again, and playing the guitar, I had to do that stuff all over again. But it was all there. I mean the bits and pieces where all there, but I didn’t have ready access to all of them.”

Within three months Garcia was writing songs and playing with his solo group, the Jerry Garcia Band. In mid-December the Dead returned to the stage, opening with “Touch of Grey,” the celebration of aging that Garcia wrote a few years ago with lyricist Robert Hunter. The concert was a triumph. Instead of falling apart after Garcia’s illness, the Dead re-emerged with new energy. The group went back on the road, finished a concert film they’d been working on for years, then recorded In the Dark, their first album in seven years, and possibly their most commercially successful one yet. To simulate live conditions, the band recorded the album in a Marin County theater.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“That’s how the energy got into it,” said Garcia. “It’s a nice little theater and it has great sound. We rented it, moved out stuff in and set it up just as though we were playing live. We didn’t have an audience, but it was that same mood. We did the tracks as though we were performing full out, so on some of those tunes I didn’t replace any solos.” Garcia and Dead soundman John Cutler produced the album, and the results are astonishing.

The compression of the guitars sounds on the recording is unlike anything they’ve managed in the studio over the years. “The arrangements are read,” said Garcia. “The mix is my understanding about how Grateful Dead music works. A lot of the producers we’ve worked with haven’t understood how Grateful Dead music works. There’s real structure to it, there’s real architecture to it and there’s real conversation, like in a string quartet, to it “The instruments speak to each other. But unless you mix it so that that’s intelligible, then it’s nonsense. That’s the sense of the music, it’s something I can’t communicate to a producer, but I can hear it.

“One of the things the Grateful Dead can do is provide that energy,” said Garcia. “The music is mostly pretty minimalist, it’s just what’s in the band—rhythm guitar, keyboards, bass, drums and lead guitar. It’s classic rock ‘n’ roll in configuration, but the style is all Grateful Dead. We get that stuff from everywhere, and that urgency is what the band can do. That’s what we’ve tried to get on record all these years and failed miserably at.”

The other band members agree that In the Dark is their first truly representative recording. “I’m really impressed with it,” said Hart. “I can listen to it, and normally I can’t listen to Grateful Dead records. We were able to capture the spirit of the band for the first time.” Bob Weir confirmed that the group’s relief over Garcia’s recovery spurred them on.

“He bounces off his little brush with death,” said Weir, “and the momentum that he picked up carried through to the recording.” That crystal-clear guitar tone did not come from any specific recording technique. “The difference is intent,” he explained. “Usually on a record I do my solos toward the end of the record, but I have this problem with my own playing. I can play okay but I can’t judge myself. When I function as a producer I’m a pair of ears and I can do that pretty well. As a performer I can perform pretty well, but I can’t do them both at the same time. So I’ve always had problems judging my own work.

“Classically, I say, ‘Ah, it’s good enough,’ I’ll do however many takes and say, ‘Ah, that’ll do.’ Then later on it turns out to be a little lame, maybe, not as good as it could have been, not what I really wanted it to be. It’s like an afterthought because it’s the thing that I end up caring the least about from a producer’s point of view. “The thing about a guitar solo is, the guitar’s register is right in the human ear space, it’s like the human voice, you can almost not bury it. It penetrates through every cut. The smaller the speakers get, the louder the guitar gets. And so it’s not a problem to mix, never a problem to get on the tape, it’s one of the easiest things in the world to record. Everything else can be a problem.

“The guitar solos on Grateful Dead records have suffered from neglect, especially, just because it was me responsible for them. That’s just the way I worked. But on this record, part of it I was able to overcome because we played live, and I actually played the solos when he laid down the tracks, so they had the energy they needed. On things where I replaced them and did them again or did a different sort of solo or left a hole for a solo, I was more concerned with making the solo concise and intelligent and work well, so I spent more time. This is me conquering the problem.” Garcia admitted to finding himself playing things on In the Dark that surprised him.

“But I always used to do that,” he quickly added. “I remember that much about my own playing. I don’t invent that much of it, a lot of it invents itself. It all comes from spending hours with an instrument, you have to put in the time, and the more time you in the more access you have to the whole file of guitar possibilities, because all music is a collection of possibilities.”

Garcia and the band had several years to play much of the new material live and develop its arrangements before making the record.

Garcia pointed out that he never played “Touch of Grey” the same way twice before it was recorded. When asked if the recoded version represents his idea of the ideal guitar sounds, he answered, “It has enough contrast with the other elements in the mix so that it comes through on its own. I selected the sound based on what it does with the other things, so it sort of fits in, it has sort of a bell-like top and that fits in with the bells and metal-like top end on the track. The process of selecting the tone on the guitar is an aesthetic process like any other, so you try a lot of different things. Most of the things I’ve tried I’ve tried in live performances, so selecting this tone was not a problem; and the band has gotten very, very good. On a great night, sometimes miraculous things happen. But for a record, it’s an okay record.”

What a long, strange trip it’s been … but of course, the Dead is more a live band than anything else, so you have to see this statement in context.

As usual, Garcia played his customized guitar on In The Dark. “I have one custom guitar which I play almost exclusively,” Garcia said. “I have others—sometimes you want a little texture, kind of a different sound or something My guitar is a mutation between a classic Fender Stratocaster guitar, which I played for years, and a Gibson solid-body like an SG or a Les Paul. It contains all sounds of the basic classic rock ‘n’ roll guitars. It does what I want it to do,” he smiles.

“It’s not really me—I don’t design guitars or any of that kind of stuff, since I don’t have that kind of mind. The guy that made this guitar, Doug Irwin, is a luthier, a guitar-builder. His guitars all have great hands. My hand falls upon one of them and it says ‘play me,’ and it’s one of those things not all guitars do. Some guitars definitely don’t do it, but his guitars do that and it’s just a special thing.

"It’s not entirely a matter of balance, it’s not a matter of dimensions, of measurable stuff, it’s something indefinable, but my hand loves it. There’s almost like a physical attraction. The man’s work is museum quality, the workmanship and the detail—it’s a beautiful instrument. But even the aesthetics of it are not what make me like them, it’s just the way it feels in my hand. I don’t know what it is, he doesn’t even know what it is, but he just builds them the way he thinks I would like them, and it works perfectly.” Garcia found Irwin by the same process of serendipity that he uses to explain a lot of the fortuitous coincidences he’s experienced.

“He was working for a friend of mine, I picked up a guitar that he had built the neck for at a guitar store and said ‘Wow! Where did this come from? I gotta have this guitar.’ I bought the guitar, and that’s the first guitar I’d gotten where he built the neck and then I said, ‘Who’s the guy who made this neck?’ and the friends of mine that he was working for said, ‘This guy over here.’ I commissioned him to build me a guitar, and he did, and I played that guitar for most of the seventies. "When he delivered it to me, I said, ‘Now I want you to build me what you think would be the ultimate guitar. I don’t care when you deliver it, I don’t care how much it’s gonna cost or anything else.’ A couple of months later he told me it would cost about three grand, which at the time was a lot for a guitar, since it was the early Seventies. He delivered the guitar to me in ’78, eight years later. I’d forgotten I’d paid for it.

“Whatever the guitar says to me, I play.”

The Dead Play Dylan

Most bands who’ve survived the near-fatal illness of their lead guitarist, then gone on to make their first record in seven years would pat themselves on the back and call it a day. But not the Grateful Dead. They decided to go out on a mind-bending mini-tour of the nation’s biggest stadiums with Bob Dylan. “It’s serendipity,” said the Dead’s lead guitarist, Jerry Garcia.

“Of course, it has to do with everybody being willing and wanting to do this. "The thing of where you almost lose a guy, whatever it was that anybody might have been reluctant to do before, it’s like, ‘we may never get a chance to do something like this again, let’s go for it.’ There is a certain opening up, loosening of that kind of spirit of adventure.”

Dylan, dubbed “Spike” because “we already have one Bob in the band,” was an ethereal presence in breaks during rehearsals at “Club Dead,” the band’s funky Marin County office-studio complex. As soon as the band set up to play, though, he crackled with a kind of musical electricity, his body coiled and radiating pure energy.

Once they start playing, the Grateful Dead and Bob Dylan are such a natural combination that you wonder why it took them this long to get together. In fact, the Dead have been playing Dylan songs for years, and the feeling is that these sessions recall Dylan’s momentous Basement Tapes, recordings with the Band in the late Sixties. “His approach is very much like ours,” said Bob Weir.

“He’s loose and we just rattle around from song to song.” “It’s hard to describe,” said Mickey Hart. “He’s a great musician, one of the most important poets of the century. He brings this whole feeling with him, his smell, musically. We’re playing all kinds of songs. We treat it all like Grateful Dead music.” Together they cover a staggering range of material—folk, blues, rock, jug band music. Dylan’s ragged, insistent guitar strumming lays a new rhythmic foundation for the Dead, creating wonderful, surprising results on songs as varied as “Tangled Up in Blue,” “All Along the Watchtower,” “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” “Serve Somebody,” “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest” and “Chimes of Freedom.”

For encores, Dylan joins the Dead on “Touch of Grey.” “A lot of the songs I know,” said Garcia, “but his versions of them now are sometimes very different from the ones I know. It’s a lot of fun. You get three or four of those serious Dylan rushes every day, that’s the fun part, and it’s authentic, it’s the real thing.” Garcia realized that there was a certain amount of rick to going out with Dylan. “Every band’s got its chemistry, got its special mojo, adding one new element to it can sometimes really screw up what’s there. Sometimes it can help, though, if you know enough about the music and you’re familiar enough with the guys that are playing.” Playing with Dylan, Garcia also tried a little steel guitar and banjo, instruments he hasn’t “really touched” for the last 10 years.

“We’re doing this voluntarily,” concluded Garcia. “We’re doing this consciously by way of an experiment. We know that it’s only gonna last so long, and maybe be an opening for future possibilities, too. There’s no simple way to characterize what’s going on here, because Bob’s got his own weight, there’s too much to him to find out about in a few weeks. He’s packing 20 years of stuff all by himself.”

“It was tour, tour, tour. I had this moment where I was like, ‘What do I even want out of music?’”: Yvette Young’s fretboard wizardry was a wake-up call for modern guitar playing – but with her latest pivot, she’s making music to help emo kids go to sleep

“One of the guys said, ‘Joni, there’s this weird bass player in Florida, you’d probably like him’”: How Joni Mitchell formed an unlikely partnership with Jaco Pastorius