“It was like watching a Polaroid develop": An oral history of Stevie Ray Vaughan's earliest days on the road

Bonnie Raitt, Buddy Guy, Dr. John, Vaughan's former bandmates and more recall the development of one of the greatest guitarists of all time

In October 1979, Stevie Ray Vaughan met a person who’d change his fate. Edi Johnson was a bookkeeper at the Manor Downs horse track outside of Austin and, after getting to know Stevie for most of a year, she asked her boss, Frances Carr, if she might offer financial backing to the guitarist, whose talent and need for help were equally obvious.

Carr was from a prominent South Texas family, not to mention a friend of the Grateful Dead. Sam Cutler, ex-Dead and Rolling Stones road manager, helped her open Manor Downs in 1975. Chesley Millikin, an Irishman who had been general manager of Epic Records in Europe and also was close to the Dead, was another friend and the track’s general manager. Carr and Millikin formed Classic Management specifically to manage Vaughan, starting in May 1980. Stevie finally had some outside support to help propel him beyond the club circuit.

After eight years of honing his craft and finding his own artistic voice, the 12-month period from January 1980 to January 1981 would prove to be pivotal in Vaughan’s career. After years of toughing it out in beer joints, couch surfing and riding in broken-down vans for weeks at a time, with no place to call home and no money in his pocket, the essential elements to Stevie’s success began to fall into place one by one.

His old friend Cutter Brandenburg was back by his side, along with bassist Tommy Shannon, who would become his closest friend. With the financial assistance of Frances Carr and the music industry connections of Chesley Millikin, Stevie finally had the tools he needed to break through.

“It was like watching a Polaroid develop,” says former Double Trouble drummer Chris Layton. “What was once a cloudy picture was coming sharply into focus.”

EDI JOHNSON, Classic Management bookkeeper: I realized immediately that he was on a different level than anyone I’d ever seen; he took you to a place where you only hear music and nothing else in your life matters. I thought he was worthy of going places and it wasn’t going to happen being paid by the door at the Rome Inn [in Austin]. I figured Frances, who was known to have resources and connections in the music business, could help.

CHRIS LAYTON: Frances was good friends with the Grateful Dead and Chesley knew the Rolling Stones.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

EDI JOHNSON: I told her this guy was really good and had a chance to go somewhere, and that maybe her friend Chesley could fly in and see him. They went down to the Rome Inn and were impressed and started talking about setting up Classic Management. One reason Stevie did not have management was his involvement with drugs and reputation for being unreliable. Anyone backing him had to be willing to not make any money for a few years.

Stevie and I had to sign every check, and that could prove challenging for me. Stevie and Lenny [Stevie’s wife] moved out to Volente [about 40 miles from downtown] because she wanted to get him away from all the people who were giving him drugs. Every Friday I had to bring the paychecks out there and get them signed so the band could get paid. I would bring any bills as well, and it could take all night to get him to sign everything. Stevie wasn’t responsible and, like most really artistic people, he didn’t have a grasp on money. He was totally consumed by his music.

ANGELA STREHLI, Austin singer: Stevie was so compelling that we all figured that sooner or later he was going to grab a lot of people. But there were so few business people in the Austin music world. As good as he was, he could have kept grinding his gears for years. Just having a manager was a big deal.

JACKIE NEWHOUSE, Triple Threat and Double Trouble bassist, 1978-’80: Chesley would tell us, “You guys have got to watch out for Stevie; keep him away from the drug dealers and make sure he’s not doing coke.” Then 20 minutes later we’d see him shoving coke up Stevie’s nose.

LAYTON: Chesley was a very high-rolling guy with a lot of great ideas, but with very little attention to what it meant to the bottom line.

JIMMIE VAUGHAN: I mean, who likes managers anyway?

JOE PRIESNITZ, Double Trouble booking agent, 1979-’83: One of Chesley’s big problems with Stevie, who he called Junior, was the lack of original material. He’d say, “All Junior wants to do is play the blues.” The band would work around Texas and we established a tour through the Southeast and Northeast, anchored by the Lone Star Café in New York City. It was a grind.

DENNY BRUCE, Fabulous Thunderbirds manager, 1977-’82: Stevie was always snorting what he called cocaine and I call crank - 'coke' that made his nose bleed with every line. He’d get going on long raps that made very little sense, such as, “In addition to being a recording artist, I need money for a medical research laboratory and to hire skilled people, because I’d like to cure poverty and starvation.” It was a speed freak’s rap.

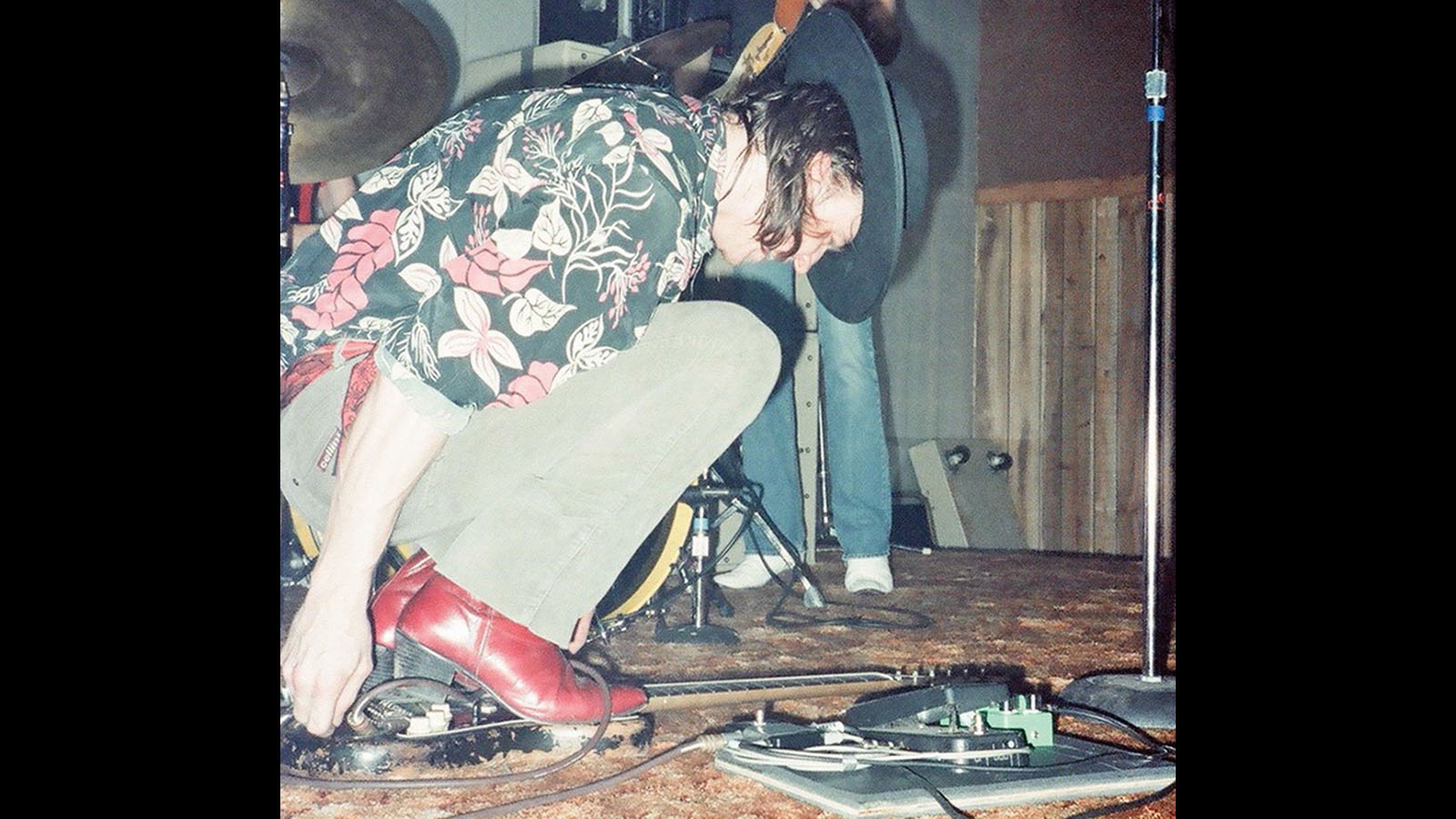

LAYTON: Speed was everywhere - it was cheap and it brought total chaos to everyday life. One day I got a call to jam with Stevie at The Hole Sound. I pull my car around back, and there’s the van sitting there running and burning up, with the radiator overflowing and on the verge of stalling out. Stevie was passed out in the driver’s seat with the door hanging open; he’d been up for days and finally crashed. I reached in and turned the motor off. The drug-induced mayhem and chaos was endless.

On October 27, Stevie and Double Trouble played at Rockefeller’s in Houston, one of their regular gigs. Old friend Tommy Shannon was living in town. After years in halfway houses and court orders that he could not play music, Shannon was working as a bricklayer and day laborer when he came to see them.

TOMMY SHANNON, Double Trouble bassist, 1980-’90: Seeing Stevie was a revelation. I thought, “That’s where I belong.” He played Texas Flood and I got goosebumps; after just a few notes it was like I woke up and thought, “I’m going for this gig with everything I’ve got.” His guitar playing had crossed the gap from straight blues, incorporating some rock and Hendrix. At the break, I went up to Stevie and said, “I belong in this band.” I was almost frantic about it. I sat in and it sounded so good!

CUTTER BRANDENBURG, Stevie’s lifelong friend, road manager, 1980-’83: Tommy had been through the worst part of his life and his hands were cut, callussed and crusty from laying bricks. You could see the pain and anguish in his eyes: one of the best bassists of all time forcibly kept away from music by legal rulings. I think it was slowly killing Tommy because he is music.

It was so sad to see him dying for someone to give him that opportunity. There was an immediate connection between Tommy and Whipper [Chris Layton] that did not exist with Jackie. It was on, and Stevie had the foundation he needed - a rhythm section he knew would follow him wherever he went.

LAYTON: I thought, “Well, alright!” Big Jack [Newhouse] was losing enthusiasm. He and Stevie weren’t that close. It was just a gig for him. Jack didn’t like the band to play loud, and Stevie was getting louder and louder. Cutter told Stevie, “Man, we could get ‘Slut’ in this band! Fuckin’ Tommy Shannon! You need to hire him.”

Stevie was hitting methedrine, snorting cocaine and drinking like crazy, but he had reservations because of Tommy’s past drug abuses. I was thinking, “What are you talking about? You’ve got a rig in your sock right now!” Cutter said, “No, man, he’s cool.” And I said, “Let’s get him! Call him up now!”

BRANDENBURG: Whipper and I talked about it on the drive back from Houston. When we talked to Stevie, he agreed this thing had to include Tommy Shannon. We went to tell Chesley and he didn’t want to do it. He felt the investment had been made in Jackie, but we said, “Chesley, if this does not happen we are going nowhere.”

The next time we went to Houston [a month later], he came to hear Tommy sit in with us, watching from the back with me as the energy level jumped 10 times. He said, “You’re right, Cutter, it’s what we have to do.” He asked what I knew about Tommy and I said Stevie and I had known him for a very long time, and he said, “I’ve seen enough and have never heard Stevie and Chris so alive. It’s now on you. Get these boys back to Austin and we will start all over.” I could hardly contain myself.

On January 4, 1981, Chris Layton drove to Houston in his Datsun 510 station wagon to pick up Tommy Shannon and help him move to Austin. The Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble lineup was set for the next four years.

Shannon’s presence shifted the dynamics and sound of Double Trouble in ways that were immediately apparent. “When I saw Stevie with Tommy and Chris, it was obvious the guy was about to blow up,” says guitarist Eric Johnson. “You can’t say too much about the magic, chemistry and alchemy between a group of musicians because those guys had it.”

“Things started to roll with Tommy,” Brandenburg said. “We now had a rhythm section that was intense, tight, full and rich, and Stevie’s confidence level as a frontman grew with every single show. Stevie could really soar and Whipper and Tommy were his wings.”

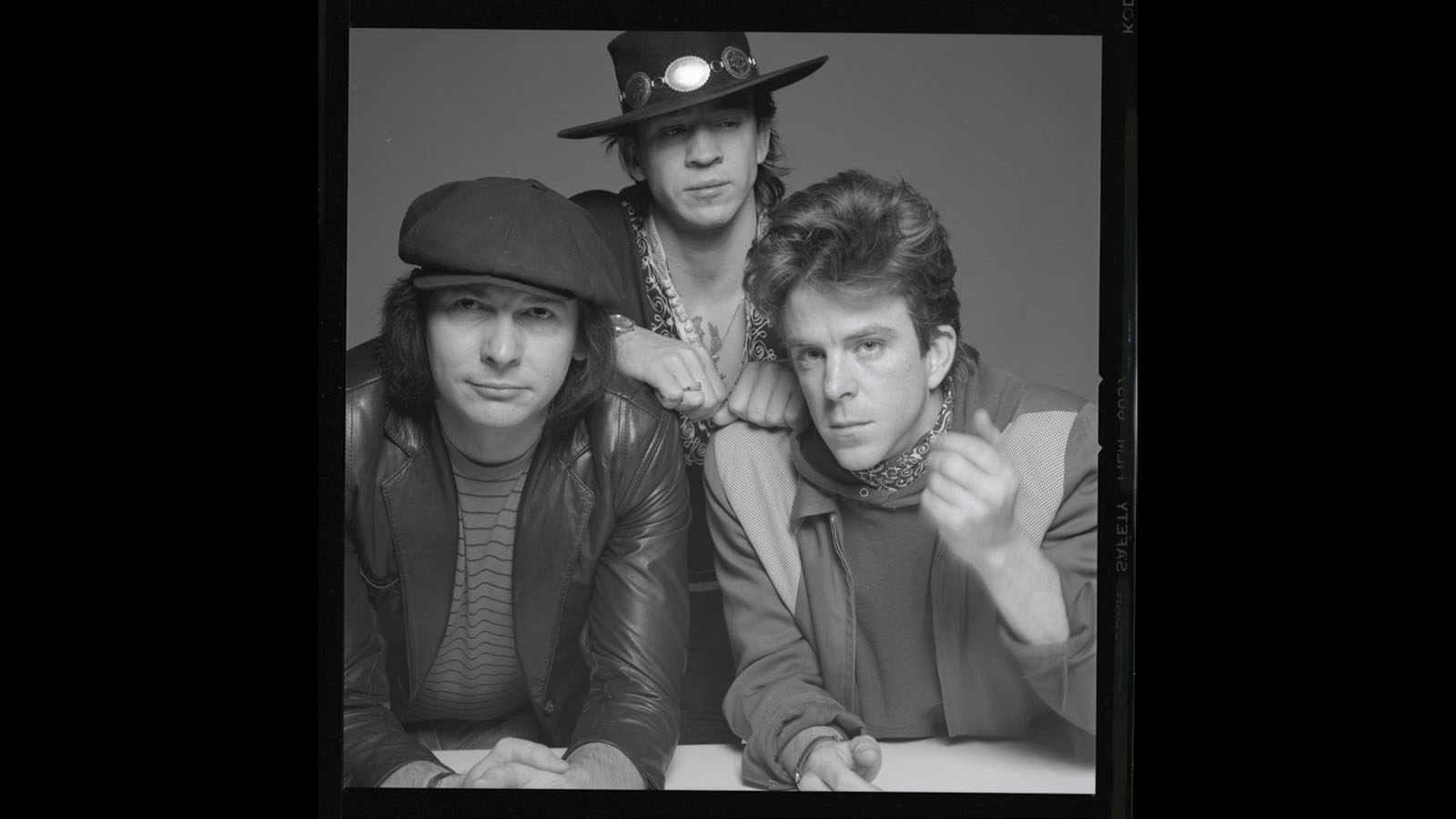

With Cutter’s encouragement, Vaughan also further developed his sartorial style, dressing in a more flamboyant, personal way that matched the music’s increasing originality and aggression. Both onstage and off, his clothes became more outlandish: heavy on the kimonos and scarves, and topped off with the gunslinger’s bolero hat that would soon define him. “He needed an image to get beyond making a little living on the Austin blues scene,” Brandenburg explained.

LAYTON: Cutter thought Stevie was downplaying himself too much. He’d say, “Stevie, you are one of the fucking greatest guitar players ever! You need to start dressing that way and acting that way!” He had the hat made for Stevie at Texas Hatters and said, “Here, man, put this fuckin’ thing on!”

BRANDENBURG: Stevie was wearing applejacks or berets while I had been wearing a large black cowboy hat for years. One night at some funky honky tonk, he had misplaced his cap so he used mine - with a scarf on to make it fit his little head - and we all liked the gunfighter image. Stevie also liked how the broad brim helped shield his eyes from the lights.

LAYTON: Cutter also said, “You should use your middle name: Stevie Ray Vaughan has a ring to it. A few years from now, people will be saying, “‘Stevie Ray’ this,” and “‘Stevie Ray’ that!” Stevie just went with it. It wasn’t part of his personality to think, “How can I promote myself and present myself as a flashy guitar badass?”

BRANDENBURG: I was the only person who called him Stevie Ray and I just thought it sounded good - as did 'Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble.'

PRIESNITZ: They were playing a series of Steamboat shows and he changed his name and the name of the band. Chesley thought it was ridiculous to have Double Trouble as part of the billing.

LAYTON: People did pick up on the name thing right away. “Stevie Ray!” And “Rave on!” for “Ray Vaughan.” People dug the hat, too, and distinguishing himself through what he wore kind of opened the door to everything else.

BRANDENBURG: Now Stevie had an image we all felt good about. Besides the talent, we had a good name [and] a look and they were working hard on songs and communicating with an audience. I also wanted them to get out of the bar gig attitude. All the tours I had been on had shown me that this was show business and it was show time. I felt we could really stand out if we presented ourselves differently than other bands in Austin, with a more polished look and approach.

SHANNON: Some of the confidence he began to feel about his playing started with the clothes. He believed he could really break out and develop his own vision.

JIMMIE VAUGHAN: We always made jokes about the way that Stevie liked to dress crazy. He just liked to dress up. He would wear anything but the kitchen sink. He wore all the scarves because of Hendrix, of course.

TERRY LICKONA, producer of Austin City Limits television show: Stevie was sensational and there was such a charisma about him. Everyone knew he was the real deal as soon as they heard him, including people like B.B. King and Buddy Guy.

BONNIE RAITT, singer/slide guitarist: Long before I met Stevie or saw him perform I had heard all about him from guys like Albert Collins and Buddy Guy, who kept running into him and being blown away.

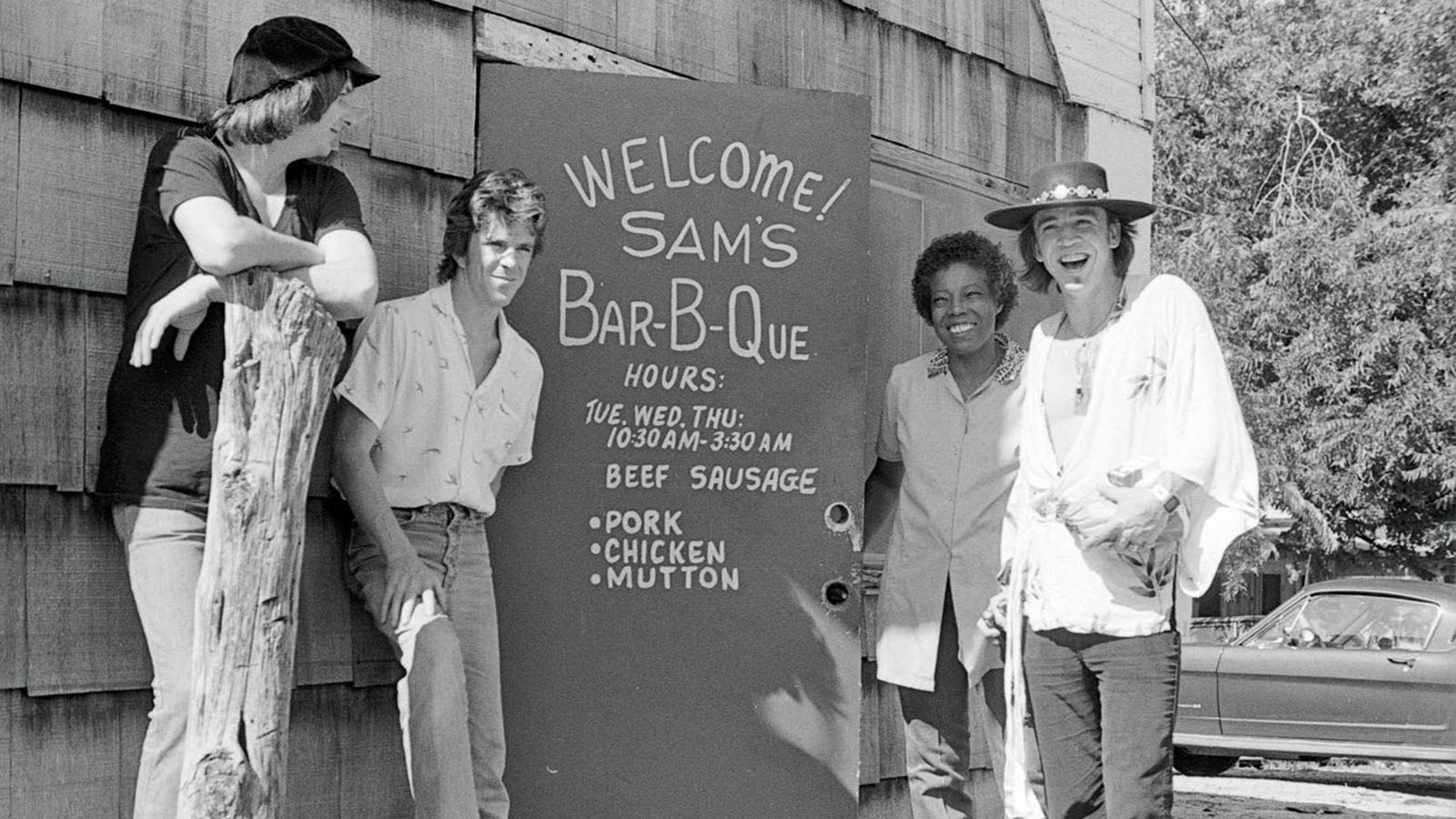

BUDDY GUY, legendary blues guitarist: I’m from Louisiana, which is close to Texas and I had no idea white people there would come out to hear you play blues, so I was astounded as soon as I walked into Antone’s the first time. Last I knew those guys were listening to Hank Williams and Bob Wills, who I liked, too. Then they slipped Stevie up there behind me. I’m like, “Wait a minute, man. Who the hell is this?”

He was hitting them notes and made me feel like I should go in the audience and watch so I could learn something ‘cause he had that Albert King tone and attack. I was just thinking, “I gotta know who this guy is.” I really couldn’t believe what I was hearing.

RAY BENSON, founder of Asleep at the Wheel: I remember standing side stage the first time I heard him play Voodoo Chile and thinking, “Holy shit! Stevie’s channeling Jimi now.”

RAITT: Just when you thought there wasn’t any other way to make this stuff your own, he came along and blew that theory to bits. Soul is an overused word, but the fire and passion with which he invested everything he touched was just astounding, as was the way in which he synthesized his influences and turned them into something so personal.

DR. JOHN, legendary New Orleans musician: He took something where there wasn’t much space to be unique and made it his own.

ERIC JOHNSON, virtuoso Austin guitarist: You forge your own voice by combining all of the heroes who have an emotional impact on you, and finding an original way to put it all together into an original voice, with your own concept, attitude and influence.

DOYLE BRAMHALL, singer/drummer and Stevie’s songwriting partner: I had great admiration for him as a musician and a person because he always lived life to the fullest. Every time you were around him, he was a constant reminder that today is all we have guaranteed.

Even in the early days, whether he was buying a pair of boots, or trying out amps, he was just completely into it. He was never satisfied with staying in one spot. He wanted to stretch and that is what made him one of a kind. Several times, when it seemed like he couldn’t get any better, he took it to another level. He was always pushing the doors open and never wanted to stay the same.

DR. JOHN: Stevie started blowing me away one night when we was hanging at his pad. He put on some trippy, difficult Hendrix album and started playing along with it, which impressed me. Then he started playing off it, getting down, improvising and I thought, “Man, this kid is jamming with Jimi Hendrix.” That’s when I saw something real unique in what he was going for, and realized that this guy was something altogether different, someone who was taking the instrument somewhere new, really striving for something big.

SHANNON: A neat thing happened when younger people started to come to see Stevie, because they didn’t think of what we were playing as blues, they responded to it as a new sound. It had more of the rock energy to it. He wanted to put his foot over the line, but for a long time was afraid of people asking, “Who does he think he is, playing Jimi Hendrix songs?” I kept bugging him to work up Voodoo Child.

When he began to trust his instincts and finally became comfortable in that role, he really took off and I saw the biggest change in his playing. And it wasn’t just about playing Hendrix stuff, because it translated to the way we played everything. That’s when he became the Stevie that everybody knows.

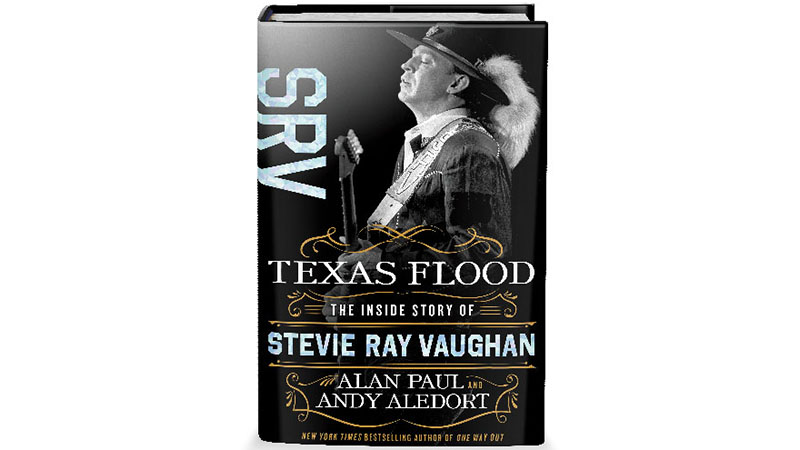

Alan Paul is the author of three books, Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan, One Way Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as Managing Editor from 1991-96. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort.

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)