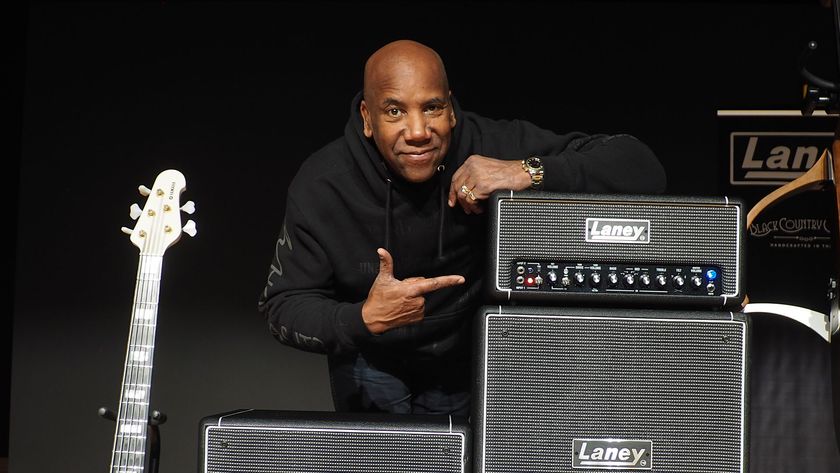

Interview: Bassist Ricky Phillips on Styx and Stones — and Beatles

When Ricky Phillips signed on as bass player for classic rock band Styx, he also signed on to the responsibilities of working with high-caliber musicians and upholding standards set not only within the band, but by their generations of fans.

Phillips agrees that it was challenging, but he certainly had — and has — the chops and resume to live up to expectations.

The ongoing quip about Phillips is that he performed in every ZIP code prior to landing his first major gig. That road experience, gained during the days of cover bands and five sets a night, seasoned him as both a musician and a team player, and led to stage and session work with a telephone directory’s worth of upper-echelon names.

Styx is on the road again, with dates scheduled through March 2012. Nightly, Phillips shares the spotlight with vocalist/guitarist Tommy Shaw, vocalist/keyboardist Lawrence Gowan, vocalist/guitarist James "JY" Young, drummer Todd Sucherman and on occasion, the band’s original bassist, Chuck Panozzo. It’s a gig he clearly enjoys, with musicians he respects.

In this interview, Ricky Phillips discusses his role in Styx, shares some memories about working with Jimmy Page and offers valuable advice about performance, attitude and mastering one’s craft.

When you play classic songs that sold millions of records, do you stay true to the original arrangements or do you have some latitude to add your touch? How do you keep this from feeling like a cover band gig?

While I was learning all the tracks, I would naturally stray in certain parts and I wouldn’t realize it. I would move on and learn more material, then I’d come back and put on the original again and go, “Oh wow, I’m not doing what Chuck was doing here.” I was concerned at first because I caught that immediately, but I knew that’s probably the natural tendency. I can’t be somebody else. I’m too far in my career, and they didn’t hire me to copy Chuck. They hired me because they wanted me to play the material and respect the material but also grow within that and play with the style that I developed over the years.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I believe we had a rehearsal hall for two days before we went out on the road, and everybody was vocal with what they liked and what they thought I should go back to, but some of the things I thought, "Oh my gosh, have I taken this too far or is this still within the margin that remains Styx?"

Todd is an off-the-hook drummer. He was voted best drummer in the reader’s poll in Modern Drummer in 2009 and he’s got chops for days. When I play with Todd, he brings out a side of me that wants to do a little bit more. A couple of times I would come offstage and J.Y. would walk up to me and say, “Ricky, you know what you were playing in the middle of ‘Come Sail Away’?” I would think, Oh boy, here it comes, and he’d say, “Keep doing that.”

So you find if you treat something with respect, and you studied the original composition, you can kind of take it and do your own thing. We change it up from night to night, all the musicians do, but we know those key spots that everyone wants to hear. It’s a pet peeve of ours to go see a band and they don’t play that guitar lick or that melody that you’ve been waiting to hear in your favorite song, so we try to stay true to those key points. If it rises up, grows and flows, I think that’s how we keep our excitement from night to night.

Your career is decades long, and your resume: The Babys, Bad English, Coverdale/Page, Styx, the session work. Why have you had such longevity? It takes more than talent. Musicians have to want you. What’s the key to being that guy?

When it works and when it’s right … to hang with Jimmy and David Coverdale and Denny Carmassi [Montrose, Sammy Hagar, Heart, Whitesnake] was really cool. We were kind of sequestered in Lake Tahoe. We would fly in and work on material — this happened over four or five months — and then we went to Vancouver to record. I was never supposed to play on that record.

David and Jimmy asked me, initially David asked me, if I would be interested in coming up and helping them work on the material. They needed to do some serious woodshedding for this record for Geffen. They were trying to see if they wanted to put together a supergroup, and I remember John Entwistle and people I really respected would be on the phone from time to time and there would be this and that going on. But I put it out of my mind and thought, This is win-win. I’m having lunch and dinner and working all day with Jimmy Page, so this is cool.

Jimmy and I would go to clubs at night and listen to bands, and I’d get to ask him about the Yardbirds — stuff I never dreamed I’d be able to do. When they handed me my ticket to fly to Vancouver and they said, “This is sounding really good; we want to cut tracks with you and Denny,” I didn’t even know how to react.

But it had become a comfortable situation. Every situation I’d ever been in band-wise — this was not really a band, but it was close — there’s always a sense of humor in it. The first band I was in that was successful was The Babys and that was a British band initially, so I understood the British sense of humor and got along like a house on fire with these guys. We had such a blast, such a good time doing it. That was a special time.

I was called by Joe Satriani. He flew me up to San Francisco and that was all because he saw me play for the first time with Mick Jagger one day in a rehearsal hall with no equipment. All of the equipment was broken down, and somebody thought they should put Mick together with me. It would have been a really cool band for Mick, but for whatever reason, that didn’t happen. As a musician, you’ve got to get yourself into a position where you are what you are. What you are may not fit in every situation, but at least you have become someone unique. There’s got to be something about you that people like, and if it fits, great, you’re off and running.

There’s another part of your question I want to allude to, which is, if you show up and you’re an asshole, you’re done, because there’s a lot of other guys on a long list that they can call. A lot of things need to connect. You’re not sitting in a cubicle in an office where nobody really has to interact with you, so you do your job and you go home at the end of the day. This is a lifestyle. This is music. It’s style. If your style doesn’t fit, it’s not going to work.

People have adjusted. I’ve seen people get into situations where they didn’t fit and they made it work. If you’ve got the time to do that, great. I guess what I’m trying to say is you’ve got to know who you are and be who you are. And that’s what you’ve got to get good at, because nobody else can be you. If you walk in and you are what’s required, you’re going to get the gig. And don’t be an asshole. And this is big too: responsibility and respect for whoever’s hiring you.

Here’s something I was thinking about the other day and this used to happen a lot. A guy would be on the road, working a lot, and he gets asked to come in, whatever the situation. It might be huge, huge, it might be one of the biggest bands in the world, and he’ll think, "Well, they know me, so I don’t really need to learn the material. I’ll just keep doing my gigs and show up and we’ll work it out on the spot." Wrong! Wrong! They hired you because you’re good, they know your work and they think you’ve got the responsibility and respect to come prepared and honor the material.

I would see people show up, wonderful players, and they never bothered to learn the material. They reach a certain level where they think they’re not required to do homework unless the band decides to give them the gig. Well, that’s all part of it, man. It never changes. All that says to the band is that you didn’t have enough respect for them to learn this before you showed up. Then you wonder why they didn’t hire you? It’s a matter of respect.

How have you adapted your style or brought your style to different projects, and what part of that style do you bring to Styx?

As a kid I was really diverse, kind of all across the board. My family was musical, so we listened to a lot of show tunes. While I was listening to The Beatles and The Who, I was also influenced by Leonard Bernstein and various other composers that were doing musicals and musical theater. Then I reached a point where I didn’t want anything to do with my family’s music; I only wanted to listen to Led Zeppelin! [laughs] Jack Bruce and Cream were huge with me, and Eric Clapton is a huge part of my playing. When he was in Cream, his note choice — I learned a lot from him, and from John Paul Jones and John Entwistle.

If a young bass player wants to get good, go back to old Beatles albums. Even if you don’t like The Beatles — shudder at the thought! — I mean, some kids don’t get it because they weren’t there during that time, but if you learn what Paul McCartney plays in “Nowhere Man” or “Penny Lane,” there are certain songs where if you played the bass part you would have no idea what the song was, but he had a way of including what was missing in the rhythm of the song, because there might have been grace notes that needed to be added to make the rhythm bigger.

He would find a way to write a melody to not only fill in the spots that were missing in the song and weren’t being played on the guitars, but also to create rhythms at the same time. It probably came to him naturally, but it’s sick how cool it is and how great. If anybody wants to really learn how to play bass guitar, I would say that’s got to be a master class that you need to dive into. John Entwistle for a lot of really aggressive, spot-on time with aggressive playing — oh my gosh, what facility — and Chris Squire falls into that sort of category as well.

John Paul Jones was a session player who came in with Jimmy Page and knew what to do with the blues influence, but sometimes with outlandish arrangements that went on and told musical stories and really, really great stuff. John Paul Jones is a spectacular bass player. Tim Bogert came out of Vanilla Fudge, played with Cactus and got real aggressive and tough with a four-string Fender bass, just clanging through distorted speakers and playing with such passion and aggression that he was almost like a lead guitar player.

I learned from all these guys. I’m not sure what I draw from each of them, but they’re all there in the arsenal. So I think I come prepared just because of my love for what I do and what I’ve tried to do, but I’ve got a lot of things to reach for. At the time, you don’t always realize what you’re reaching for, you don’t know until afterward, but you’ve got to be able to do that.

Going back to your comment about Clapton: When did you begin to understand the importance of note choice?

When Hendrix came out, I was too young to be able to play what he was playing. I almost gave up at a certain point. I was frustrated. I wasn’t there yet. But I would never stop listening. My brother had an old record player made by Singer and it would automatically turn off after the turntable got to the end. I’d go to bed, put both of the little speakers on each side of my pillow and I’d go to sleep listening to Hendrix every night. Just trying to absorb it, I guess. I don’t know what I was doing! I just wanted to hear it all the time. His note choice was — God, nobody was doing what he was doing. Who chooses those notes? What a crazy, crazy formation of notes that are so cool!

I realized that Clapton not only ended his phrases with a cool note that made you go “Ohhh” at the way he ended it, but there was so much stuff in the middle. They call him Slowhand, but what he was doing with that slow hand was stuff that nobody else could quite figure out. So whenever I would work on songs, I didn’t want to just pound out eighth notes. You go, “What can I do with that to throw in a note that makes you go ‘Oh wow, I want to play that’?” When I first played “Day Tripper” — that’s fun to play; you want to play it all day when you first learn it. I wanted to try and write bass parts that were fun to play, with the right note choice. These guys kind of led me along my path. I wanted to be able to play their game and be mentioned in the same phrase, which I rarely am! But it’s great to try. That’s where you want to end up.

Alison Richter interviews artists, producers, engineers and other music industry professionals for print and online publications. Read more of her interviews here.

Photo: Jay Gilbert

Alison Richter is a seasoned journalist who interviews musicians, producers, engineers, and other industry professionals, and covers mental health issues for GuitarWorld.com. Writing credits include a wide range of publications, including GuitarWorld.com, MusicRadar.com, Bass Player, TNAG Connoisseur, Reverb, Music Industry News, Acoustic, Drummer, Guitar.com, Gearphoria, She Shreds, Guitar Girl, and Collectible Guitar.

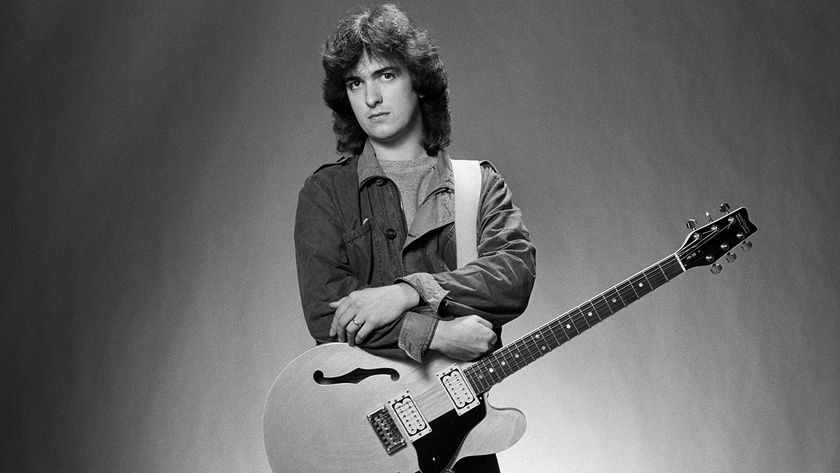

“The six-string bass guitar was a dream – if Leo Fender could come back today I think he would approve”: 10 6-string bassists you need to know

“It’s great to tap like Les Claypool and thump like Marcus Miller, but the world of a studio bassist is different”: Having graced hits by OutKast, TLC, and Usher, LaMarquis Jefferson carved a niche in a scene long dominated by synthetic low-end