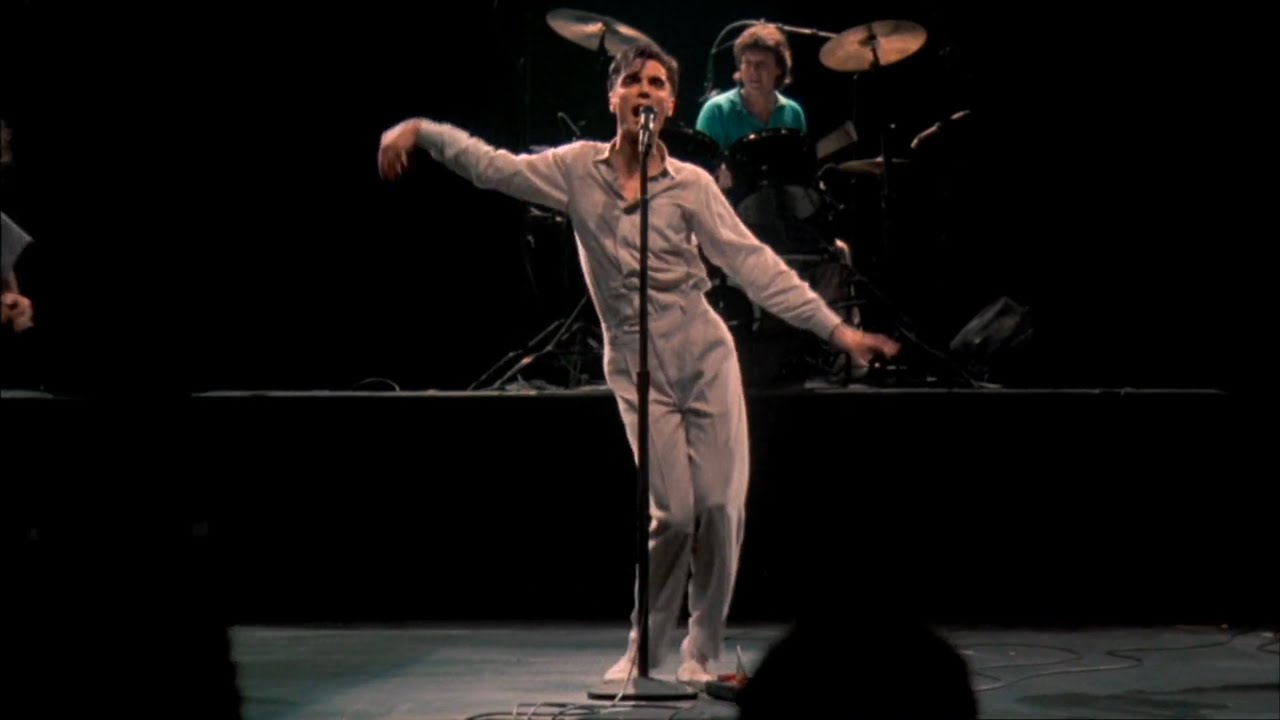

“I was really broke. The only way I could get to New York to try out for Talking Heads was to take a family who were moving there in the band van”: Jerry Harrison on making Talking Heads’ 1977 debut and rejecting blues-rock to shape the CBGB guitar sound

Granting a rare interview to promote Talking Heads’ newly reissued debut album, the new wave pioneer holds forth on everything from the thrills of the CBGB scene to the perils of mimicking your heroes

Take a late-night walk down the street known as Bowery in New York City, stop outside the John Varvatos fashion boutique at 315, and with a little imagination, you can still hear it.

The subterranean clatter of drums, the furious pelt of cheap guitars and, every few minutes, another rabble-rousing count-in (“1-2-3-4!”). Depending on the sharpness of your mind’s eye, you might even see the leather and curled lips of the bands and punters flowing into the fabled CBGB club that stood on this spot in the late ’70s.

It’s all gone now, of course (along with many of the greatest exponents of punk and its open-minded offspring, new wave). But you couldn’t ask for a better chronicler of that cultural flashpoint than Jerry Harrison.

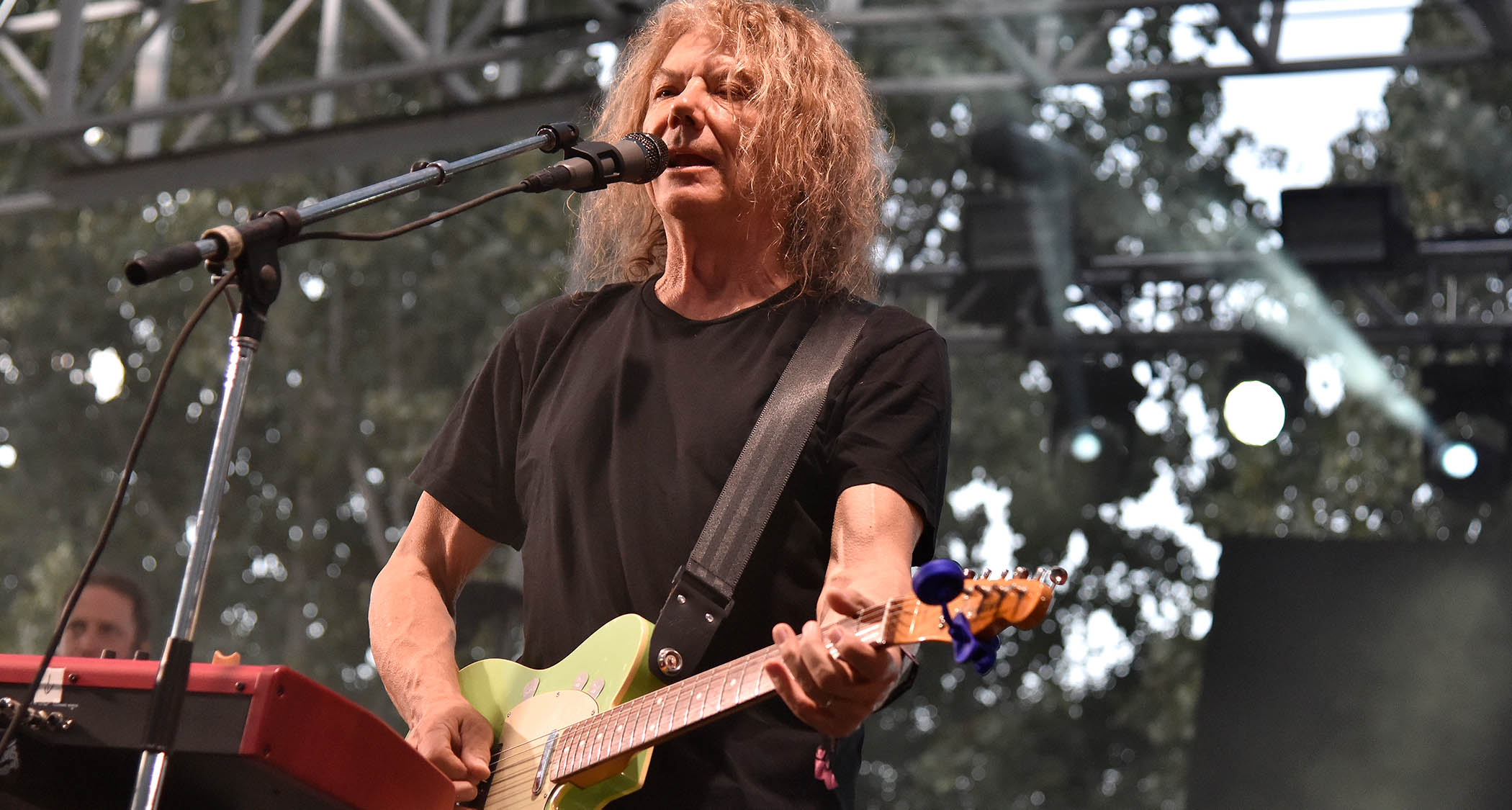

Cutting his teeth with proto-punks the Modern Lovers, the Milwaukee-born guitarist joined the wilfully artsy, fiercely individual, genre-eluding Talking Heads just in time for their studio debut before applying his thumbprint to a catalog that took in everything from funk to Afrobeat.

Almost half a century later, as that seminal first album, Talking Heads: 77, is reissued as a Super Deluxe Edition including live cuts and curios, the 75-year-old guitarist still sounds staggered by his musical fearlessness as a young man.

Are you pleased with the reissue?

“Very much. I’m delighting in all these different versions of the songs, and the growth of the guitar parts that David [Byrne, frontman] and I are playing. It’s like, ‘Wow, there’s so many different ways these songs were played.’ I’d kinda forgotten, because you zero in on the album version.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“The re-release of these records reveals this sort of growing complexity in the jam sections. Particularly on Psycho Killer – the ending of that song would be this long rave-up, to use some ’60s terminology.”

Talking Heads recruited you shortly before that debut album. The story goes that you were intrigued – if not exactly impressed – when you saw them live.

“The first time I saw them, I thought they were totally unique. But then, when I saw them again maybe six months later, I realized how brilliant it was. Then they asked me to come and try out for them.

“That’s an amusing story. They were looking for a keyboard player. My previous band, the Modern Lovers, had sort of bankrupted me. I was really, really broke. So the only way I could get to New York to do the trial for the Talking Heads was to take a family, who were moving there, in the band van.

“When we got the van full, there wasn’t enough room to put the organ in. So I showed up with a guitar. They said, ‘We thought you were a keyboard player.’ And I said, ‘Well, I am, but let’s just play some music.’ They lived on Chrystie Street in this funky loft, and we went out for Chinese food, came back then started playing.”

“I wanted to enhance the way they sounded, whereas I think a lot of other people who tried out felt they should show how dextrous they were [and show] all the things they could do.

“I tried to be a light touch and listen to what Tina [Weymouth, bass] and David were playing, sometimes doubling or going off on a part influenced by both the bass and the guitar. And so it seemed a little more seamless.

“It was fun playing guitar with David, and I’m not going to say that we got to the point of [Television’s] Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd, but we had great interplay and this kind of back-and-forth.”

One thing that strikes you hearing the ’77 album now is that you never played the guitar clichés. Where did that rebellious streak come from?

I never learned to play guitar by trying to mimic other people. I’m also not the best person to go jam with. I don’t hear licks and changes that way

“It’s because I never learned to play guitar by trying to mimic other people. I’m also not the best person to go jam with. I don’t hear licks and changes that way. If I have to go play with someone, it’s like, ‘Give me a chord chart, let me listen to it, give me a little preparation’ – because I just never made myself as facile at that.

“I also noticed that with some guitar players from high school, the ones who had learned every lick that Eric Clapton or Jeff Beck did, if you knew those records, you recognized the solos. But the best players finally got to the point where it felt like their own.

“It’s like when I produced Kenny Wayne Shepherd [on 1997’s Trouble Is…]. He’s obviously influenced by Stevie Ray Vaughan and studied Albert King and various other great blues players. But when I hear him, I still feel like his internal mind is coming up with the licks, and they’re his at that moment. But a lot of people who spent their time learning to copy other things, they never quite escape it.”

Do you recognize yourself as a guitar player on that debut album?

“Well, I think I’ve evolved a long way from then. I mean, I can hear it all the way through the development of the records. The peak being, I would say, Fear of Music [1979]. When I joined Talking Heads, I had played guitar for not that long. So yeah, I think I got to be a better and better guitar player. And a better musician all around.

“I mean, there’s nothing like going on tour for a musician. You can sit around and practice at home, but when you play with other people, and put yourself in front of an audience, and you’re seeing their feedback… whether they’re wincing if someone hits a bad note, or they’re totally excited, if you’re sensitive to it, that feedback makes you a better player, a better singer and all of those things.”

CBGB is often described as punk and new wave’s ground zero. What are your feelings about that late-’70s scene now?

“I give Hilly Kristal [CBGB owner] all the credit in the world. He was very fair. The band got the majority share of the door and he let musicians hang out there. So it drew us all together. The CBGB scene focused it. To have this one club, y’know?

“At the time, the record companies were into bands like ELO, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Yes – what I call ‘academy rock.’ Like, everybody had to go to the music academy to qualify to play in these bands.

“And the Modern Lovers were part of the beginning of this idea – and then of course the punk movement was the flourishing – that, ‘No, we want to go back to real, straightforward rock ’n’ roll. We have something to say and we’re gonna say it.’”

“It’s about the energy, even the sex appeal. Nobody’s playing a 15-minute solo. The Ramones are the ultimate example of this. They’d do a 30-minute set and play 16 songs, y’know? Also, with almost all the CBGB bands, there was a rejection of blues-rock. Y’know, we don’t bend notes.

“But it was also the fairness. Because the record companies were ignoring it, everybody was mutually supportive and excited by the bands. It’s like, the Ramones, Television, Talking Heads and Blondie are the sort of pillars of that early movement. And then you have bands like the Dead Boys and Tuff Darts.

“Each of us were really different: different influences, different ideas about what excited the audience. But we all respected and liked each other.

“The minute we all got signed and were leaving New York and going on tour around the world, it became more competitive. I’m not gonna say ‘less friendly.’ But of course we weren’t seeing each other every week when we were all hanging out at CBs.”

What do you remember about the Talking Heads: 77 sessions at Sundragon Studios?

“We had this producer who didn’t understand us at all, Tony Bongiovi [cousin of Jon Bon Jovi]. He really understood the technical sound aspects of music, and he brought in Lance Quinn as a co-producer. Lance was also a session guitar player, and if Tony would get frustrated when we were slow to play a part, he would go, ‘Lance! Go play it!’

“But then Lance would say, ‘Tony, for me to play it like they do will take much longer than just getting them to play the part right.’ Tony would be reading magazines about airplanes. Which I think is one of the reasons why, when we met Brian Eno, we’d go, ‘We really want to have a producer who thinks like we do.’”

Lou Reed was also briefly in the frame to produce 77.

“I think it would have been different. But I think Lou, at that time, would have been impatient. I’d known Lou when he was at the height of his speed addiction, when he did Rock ’n’ Roll Animal [1974].

“He gave David an interesting piece of advice, though, which was, ‘Wear long-sleeve shirts; no-one wants to look at hairy arms.’ The other thing he said was, ‘Once you have a look, never change, because you want people to recognize you.’ Of course, his good friend David Bowie turned that on its head.”

Journalists always struggle to put Talking Heads in a genre. What do you think?

“We shared with all the other CBGB bands this idea that we’re gonna do things our own way. I think that when we did Take Me to the River on More Songs About Buildings and Food [1978], everyone went, ‘Oh! I was trying to figure out what their influences are, but it was really R&B.’ That was the thing we all loved.”

Even on the first record, there’s the African-sounding guitar on The Book I Read.

“That side really came alive when we did I Zimbra on Fear of Music. We had all been listening to Manu Dibango and Fela Kuti. But that song almost didn’t make the record because there was no singing on it.

“So David and I flew back from Perth to New York on this 30-hour flight to work with Eno, who came up with this idea of using dada poetry as lyrics. I think we all recognized, y’know, ‘Let’s keep going with music like this…’”

You’ve always been a Fender player. What was the key guitar on that debut?

“When I started playing guitar in the Modern Lovers, Jonathan Richman had switched from a Telecaster to a Jazzmaster. So he gave me his [mid-’50s] Telecaster, and that was the guitar I started with. Then I bought that black ’64 Stratocaster that I always used. So those were the two guitars I had for that first Talking Heads record. I also had a little Epiphone I used on No Compassion in an open tuning.”

What are you playing these days?

“I actually still have that yellow Tele and the original black Strat. I also have a Fender Custom Shop Telecaster that I put a hotter pickup on, and that’s become the guitar I play when I’m with Adrian Belew.

“Because it’s a guitar that, were someone to steal it, I could probably have it remade. I don’t want to take out the ones that go back into the ancestry. It’s like you leave the guitar onstage and someone runs up and takes it. It’s happened.”

The Talking Heads were very careful with our money, because we never wanted to be indebted to the record company

What guitar amps were you plugging into for 77?

“I very much followed David’s lead. He was playing a Vox Super Beatle, and I got one of those. Also, by that point, I bought these used Ampeg V4s and bottoms with the 4x12s that I think both David and I used. The Talking Heads were very careful with our money, because we never wanted to be indebted to the record company – it’s really essential not to do that.

“Later, Tina, David and I started using Gallien-Krueger, and so it was a solid-state sound, not a tube sound. And then, when Adrian joined the band, he introduced us to the Roland JC-120, and I loved the chorus on that. Nowadays, I play a Twin Reverb and I have a Deluxe that is my favorite.”

Did that first album turn Talking Heads into all-conquering rock stars?

“Well, it certainly didn’t make us rich and famous. We would go around to the radio stations. And it was at the time when all the FM radio stations had windchimes, like [whispering DJ voice], ‘You’re listening to WCOC Buffalo,’ y’know?

“And they’d go, ‘I’ve been listening to all this punk music coming out of New York and I literally can’t stand it. But out of all of them, you’re the one band that I can tolerate…!’”

- This article first appeared in Guitar World. Subscribe and save.

- Talking Heads: 77 (Super Deluxe Edition) is out now on Rhino.

Henry Yates is a freelance journalist who has written about music for titles including The Guardian, Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a talking head on Times Radio and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl and many more. As a guitarist with three decades' experience, he mostly plays a Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.