“Roxy insisted I have a white Strat – I bought that guitar off Brian Eno, who bought it off his milkman for 30 quid!” Roxy Music’s Phil Manzanera on how he found his bargain Firebird and why he has no regrets about rendering a ’51 Tele “valueless”

The Roxy Music guitarist invites us into his London studio to take a look at the guitars that he cut five decades of hits with, and tells us how a globe-trotting childhood led him to art-rock Shangri-La in ’70s London

There can be few guitarists who have roamed so widely through the landscape of pop music as Phil Manzanera. Born in England but raised in, variously, Cuba, Venezuela and Hawaii, his playing has always possessed a deep spirit of musical adventure.

From era-defining avant-garde rock with Roxy Music to Latin-infused prog and dalliances with experimental synth in his early solo career, his vagabond muse has never settled down. His gift for playing just exactly the right phrase at the right time, combined with a leftfield sensibility that always results in work that’s full of surprises, means that over the past five decades, his music has never lost its vitality.

As he releases a heavyweight 11-disc retrospective of his solo albums, we join the ever-affable guitarist in his London studio, where he has brought out one or two old guitars he thought we might like to see while we chat about his iconic recordings.

Your Cardinal Red Firebird VII has been a constant companion over the years – how did you get it and what did you use it for in your solo work and with Roxy Music?

“So this is a guitar that I found in the back of the Melody Maker. They used to have ads for guitars for sale in 1973 and I rang up, and it wasn’t in a shop or anything, it was a private individual. So I went to this very posh house in Regent’s Park in London, knocked on the door and this 16-year-old American kid held it up, and I said, ‘It’s a red guitar – I’ll have it!’”

“I didn’t even plug it in. I think it was about 120 quid, but I needed something flash for my Roxy stint. I had a white Strat – they had insisted I have a white Strat, which is another story because that was a guitar I bought off Brian Eno, who bought it off his milkman for 30 quid! But as a youngster, I had bought a red Höfner Galaxy when I was 10. So I was used to having a flash red guitar.

I needed something flash for my Roxy stint. I had a white Strat – they had insisted I have a white Strat

“The Höfner Galaxy was from Bell Musical Instruments in Surbiton in the UK, where I had been sent from South America to a boarding school in South London. So anyway, I saw this red guitar and I thought, ‘Wow, that is different. I’ve never seen anything like it before.’

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“And it turned out that the boy’s parents had come over from Kalamazoo and they’d bought it for him – in a custom colour red for his birthday. For some extraordinary reason, he didn’t want it or maybe it was too unwieldy or he had given up guitar and taken up cricket or something. I don’t know, but I said, ‘Thank you very much – I’ll have that!’ It’s become my signature guitar, and I first used it on the third Roxy Music album, Stranded, in particular on the track called Amazona.

“What’s particularly good about this guitar is it’s always been great for recording. The tuning aspect is not brilliant, but for recording purposes… it just likes going onto analogue tape. And so this was used in quite a lot of the Roxy songs – I’d use this for something on every album. I’d also use a ’51 Telecaster and a Gibson Les Paul. But this one has appeared on every album I’ve done, including all my solo albums.”

“Most of the Diamond Head album was done with this guitar, but I tend to use quite a lot of different guitars on the albums for different tracks or different bits of music – you use different sounds and you play in a different way with each guitar. It creates its own unique sound, and this one sort of plays itself in some ways.

“I came up with the riff that ended up being sampled on No Church In The Wild [by Jay-Z and Kanye West] – which was originally a riff on a track from one of my solo albums called K-Scope – when I was watching the telly and just messing about on this guitar. And that’s what I came up with; it’s particularly good to play that on this guitar.

“I wouldn’t have come up with that on a Strat or a Telecaster or Les Paul or something. There’s something quite tight about the width of the neck up here, and when you play an A chord it’s got a very nice, tight sort of sound. So yeah, that’s a very technical aspect of guitar-ing, I suppose. That’s what makes this one come up with these riffs that sort of appear out of nowhere.”

What was your backline gear back in the early days of Roxy Music’s success?

“Well, what was considered the best thing to have in those days? You either had a Marshall or you had Hiwatt. And I had a Hiwatt 100 top, I think, but it had a special switch on the back so you could make it 30 [watts in output] to give it an extra poke [accessible natural overdrive] and a 4x12 cabinet, which had Celestion speakers in it. I also had a Fender Twin Reverb that I would use depending on what guitars I was using. That was the basic amplification.

“Then me and Eno worked together a lot on having my guitar signal as a sound source for him to treat through his EMS VCS3 synthesiser, and we also both had Revox tape recorders that we had modified by a very good company called Taylor Hutchinson at the time – and I only remember that name because the sticker is still on my Revox.

“It had something called Varipitch and Sel‑Sync on it, which you could use to speed up and slow down the speed of the motor. Therefore if you were using it as an echo unit, you could speed up the echoes or slow them down and create interesting effects.”

“These were the days when there were no pedals and things. There was maybe a fuzz box pedal and maybe an Echoplex or Watkins Copicat echo unit. So you had to use what I call the sort of ‘Heath Robinson method’ of trying to get weird sounds by doing different things – pimping machines to do things they’re not meant to do, sticking sticky tape on the capstans of tape machines to create a flutter, a wobbly kind of sound.

Really, I’m not a songwriter, although I have written about 60 songs with words over the past 50 years

“But we also had modified DeArmond volume pedals to control the slider on the Varipitch on the Revox tape recorder, which I still have. The combination of me sending a wobbly sort of signal to Eno, then him treating it and putting it out, along with my normal guitar created this unique sound, really.

“And then when he left the band, I had a special [EMS] VCS 3 guitar synth made that was controlled by these DeArmond volume pedals, which we still have and which we’re trying to get repaired so that it still works.

“It created a unique sound – and the best example of that is on the track Amazona. You can hear the combination of the Revox tape recorder with this special guitar synth that was miles ahead of its time. We’re talking about 1974 and it sounds like some strange underwater guitar. To be fair, I don’t think it ever worked properly after that! But it was captured on that one track. So it is a unique thing.”

How did your solo career get started? Because you were very much active with Roxy Music when it began.

“For a start, when I call it a solo career, there was really no intention of going solo. I had the opportunity because all the other guys in Roxy had done solo albums almost immediately after we started. I mean, Brian Ferry and I played on quite a few of them. So I put up my hand and said, ‘Can I do a solo album?’

“They kind of said, ‘Go away. Yes, you can do one.’ I thought, right, I’m going to do music I couldn’t do within Roxy and indulge myself in a kind of music, whether it’s prog rock or Latin music or just anything I wanted, with my friends who weren’t necessarily in Roxy. Although I did end up using everyone in Roxy, except for Brian Ferry because he was a singer, and I obviously didn’t want [my work] to go anywhere near the unique Roxy sound.

“I then embarked on this so-called solo career of just having fun with my musician friends, making music. And, really, I’m not a songwriter, although I have written about 60 songs with words over the past 50 years.”

“But really I consider myself a musician who just likes to try out lots of different musical genres, and I realised I had a lot of music in me that wouldn’t just fit into one Roxy album, so I had to find another outlet. Which, to be fair, all the other people in Roxy were doing – and that continues to this day.

“Both the Brians are bringing out music that is their own kind of thing that wouldn’t fit necessarily within a band-type format. Andy Mackay and Paul Thompson help on all of our stuff.

“I guess there was a lot of music within all the people in Roxy that had to find another outlet. Mine became this sort of solo thing and now I’ve put it all together in the 50 Years Of Music boxset and it’s 11 CDs’ worth.

“So whether anyone’s got the patience to listen to it all I don’t know [laughs]… but I had to obviously go through it all to remaster it and get it onto the boxset. It covers a wide range and it really does reflect me outside of Roxy. I also brought out a book, a memoir, which really was me trying to make sense of the last 50 years and also beyond that, with my family, my South American heritage and everything.”

“So this is another way of tidying up those sort of 50 years in a sort of musical form, putting it together in a boxset so I can say ‘that was then’ – now I can look forward to new stuff for the future.

“But it has also made me realise how important music has been for me since my mum started teaching me guitar in Cuba in 1957. It’s been the constant thing that’s gone through the whole of my life – it, and the guitar, has been my friend. And these guitars [in this feature] have been used and have been with me on this whole journey. It’s kind of weird, but that’s guitarists for you.”

Tell us about your modded Tele – it’s been almost a Fender counterpart to your Firebird in terms of the amount of Roxy tracks you’ve made with it.

“It says here that the serial number is 1443 – supposedly it’s a 1951 Telecaster, which would in theory be worth a fortune.

“In practice, though, I rendered it valueless because a good friend of mine, Eric Stewart from 10cc and Lol Creme, in 1975 I think, said, ‘We’ve got this great guitar guy up in Manchester called Ted Lee. Let him have a go with your Telecaster. He’ll strip it down, revarnish it, put a humbucker on it, put Gibson frets on it…’ and thus rendering it from a guitar that’s probably worth six figures to probably zero [laughs]. However, it sounds fantastic and all I was interested in was having a guitar that was great to play.

“Back in the early ’70s, nobody was particularly interested in the value of a guitar. The value was in the sound and the playability of it, you know? So this was used on pretty much every Roxy album from around 1974, which is when I think I got it.”

“One of the most famous things I played on it was [the intro to] More Than This. And I’d forgotten this… but Rhett Davies, the co-producer on the album, was doing an interview the other day and he said that we were trying for ages to find a riff for the beginning of More Than This.

“Apparently, I was tuning up and they said, ‘That’s it!’ I said, ‘What?’ And they said, ‘Just keep playing that [riff] right through the thing.’ [A simple fingerpicking pattern played on a powerchord shape, as when checking how ‘in’ a chord sounds when tuning up – Ed]. And that’s how that ended up being that iconic riff, which is hilarious, really. It just shows you.

“I also played the riff from Over You on this Telecaster. I’d just got my original Gallery Studios and I was sitting at this little sort of bench thing behind the desk. Brian Ferry had come over to the studio and, Brian’s not famous for playing the guitar, but there was a bass there and so he picked up the bass and I started doing that riff – that’s the first thing we did in the studio.

“I started playing and he started playing a bit of bass, and from that we built the song Over You. So hooray: the first thing we did in that studio and we’ve got something that could be a single from something as simple as that… but it’s just beautifully clean.”

Your guitar parts always seem perfect for the song – they’re never too much or too little. How did you develop that knack?

“I mean, one is always trying to start with something simple – especially once I joined Roxy. Before that, I was playing kind of prog rock in 13/8 or something like that, you know [laughs].

They said, ‘Don’t worry, Eno will teach you because he’s banned from being on stage because he makes everyone too nervous

“That’s what was interesting about Roxy stuff, and I guess I continued that method of working into all my solo stuff, which was to create the musical context first, then – if it was going to be a song – try to work with someone who could create a top line and discuss what the lyric might be…

“Or if it’s going to be an instrumental, then the one thing about instrumentals is that you can give it any title you like, and now revisiting all those 100-odd tracks on the box, I see a lot of them have been named after certain moments in my life, like the track Diamond Head. Diamond Head is the name of the volcano at the end of Waikiki Beach.

“When I lived in Hawaii and went to school there, every day, I’d get on one of those American-type school buses and meet my mother at Waikiki Beach and go surfing, aged about eight or nine – and there was Diamond Head. So when it came to having a name for my first solo album, I called it Diamond Head. Now, I think there was a heavy metal band who called themselves that as well, but to me it was Hawaii.”

How did you first become involved with Roxy Music?

“Well, I answered an ad in the Melody Maker and it said something like, ‘guitarist wanted for avant-rock group’. I can’t remember if it said ‘no time wasters’ or ‘no wine tasters’, which was the normal joke at the time.

“But I had heard the name Roxy Music because Richard Williams, who was a great journalist – still is – worked for the Melody Maker. He had this special column that you could send tapes in to and so Brian Ferry had sent in some of the embryonic Roxy demos.

“As it happened, the band I was in at the time, Quiet Sun, had also sent in tapes and [coverage on their respective demos] came out consecutive weeks. We looked at the Roxy one, and I thought, ‘This is a lot more interesting than our one!’ And then the bass player in Quiet Sun joined Robert Wyatt’s group [Matching Mole], and so I was without a gig. Someone said, ‘Well, why don’t you try for that band, Roxy?’”

“I went along to audition in a little working men’s cottage that Brian and Andy were sharing in Battersea in London. At the time, Brian was teaching pottery at a girl’s school in Hammersmith and Andy was teaching music. They were a bit older than me, and Eno was there, and I thought, ‘These guys are weird and wonderful and different. I want to be a part of this.’ So we talked and I played – and I failed the audition. So I thought, ‘Oh, damn. These guys, I know they’re going to make it; there’s something unique about them.’

“Then, for one reason or another, it didn’t work out with Dave O’List [Roxy’s original pick for guitarist], so they called me back – supposedly to mix the sound – and I said, ‘Well, I don’t know the first thing about mixing the sound.’

“But they said, ‘Don’t worry, Eno will teach you because he’s banned from being on stage because he makes everyone too nervous – so he’s in the audience, mixing the sound.’ Well, by ‘the audience’ I mean, we’re talking about pubs that had about 20 or 30 people! And it’s true, he was there because I saw a gig and everyone was coming up to him and saying, ‘What does that do? What’s that synth do?’ And all this.”

“So I got to this derelict house near where we are today. It had electricity, and they said, ‘Oh, there’s a guitar there. Do you want to have a go?’ I half knew this might happen, so I’d learnt the [Roxy Music] numbers secretly.

“They were playing a little bit of a game with me and so [going along with it] I said, ‘Just show me once how to play it.’ So they showed me and then it was, ‘Right, let’s play it.’ And I played it. They did this about five times and they said, ‘Wow, this guy’s great!’ [Laughs] ‘Would you like to join?’

“I joined, I think two days after my 21st birthday – and a week later we signed the first record contract. Four gigs later, we were in the studio recording the first album. Three months later, it came out on the same day as Ziggy Stardust, we supported Bowie at a pub in Croydon the same week, and the album went Top 5. And here we are, 52 years later. I’m just in the right place at the right time – touch wood.”

- 50 Years of Music is out now.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.

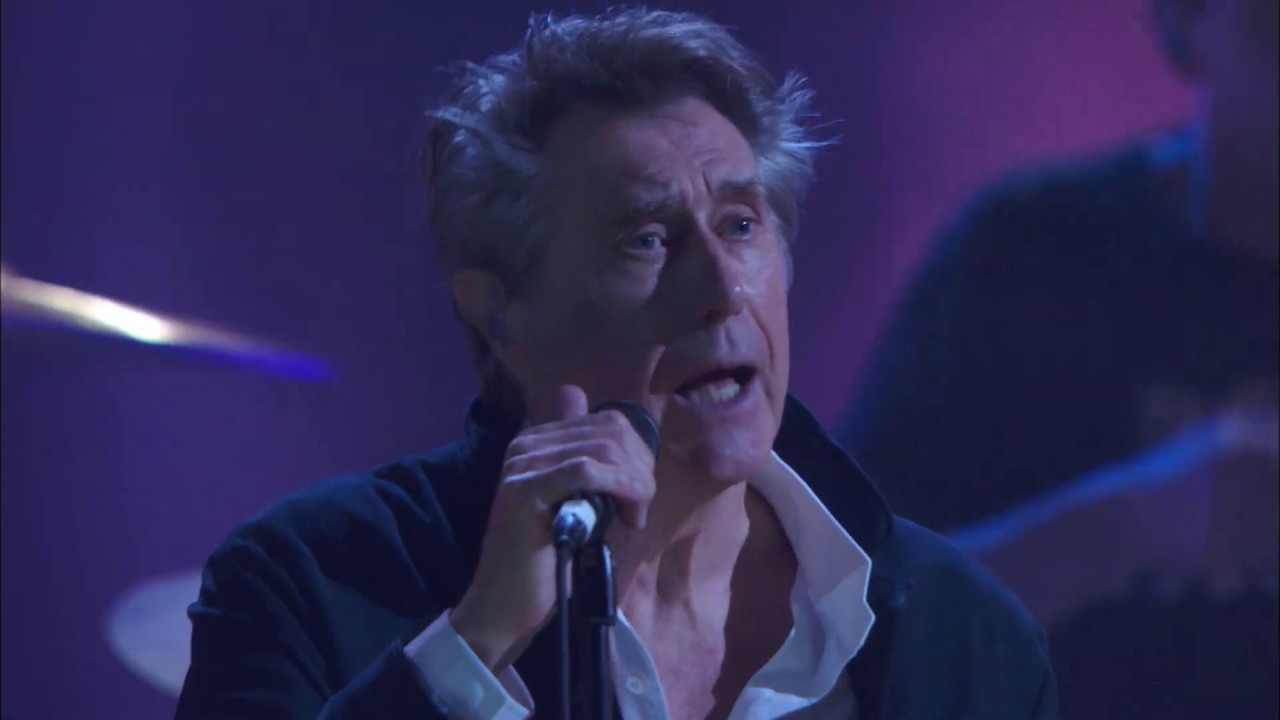

![[HD] Roxy Music - Avalon (Live 1982) - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/sPt8EvpZWF8/maxresdefault.jpg)