“He showed me the Rickenbacker he used with the Beatles at Shea Stadium. It still had the song list taped to the side”: Released weeks before his murder, John Lennon’s final album paired him with some of the era’s finest session guitarists

Hesitant to step back into the spotlight but powered by renewed creative energy, the former Beatle joined forces with Earl Slick, Hugh McCracken, and – though their collaborations weren't released for a number of years – Cheap Trick

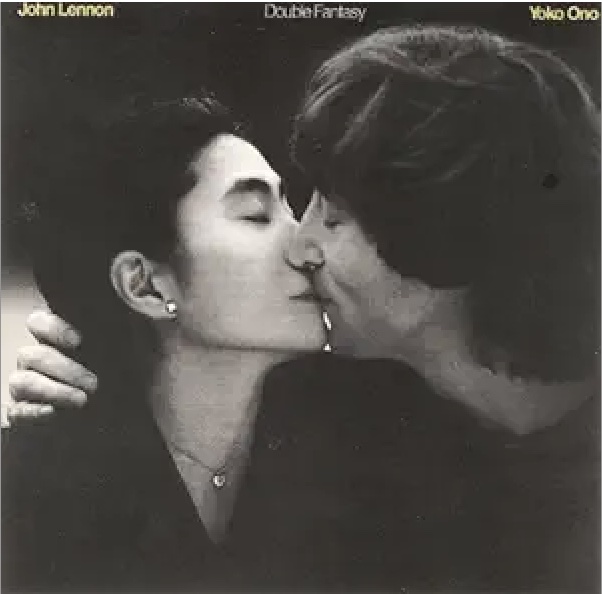

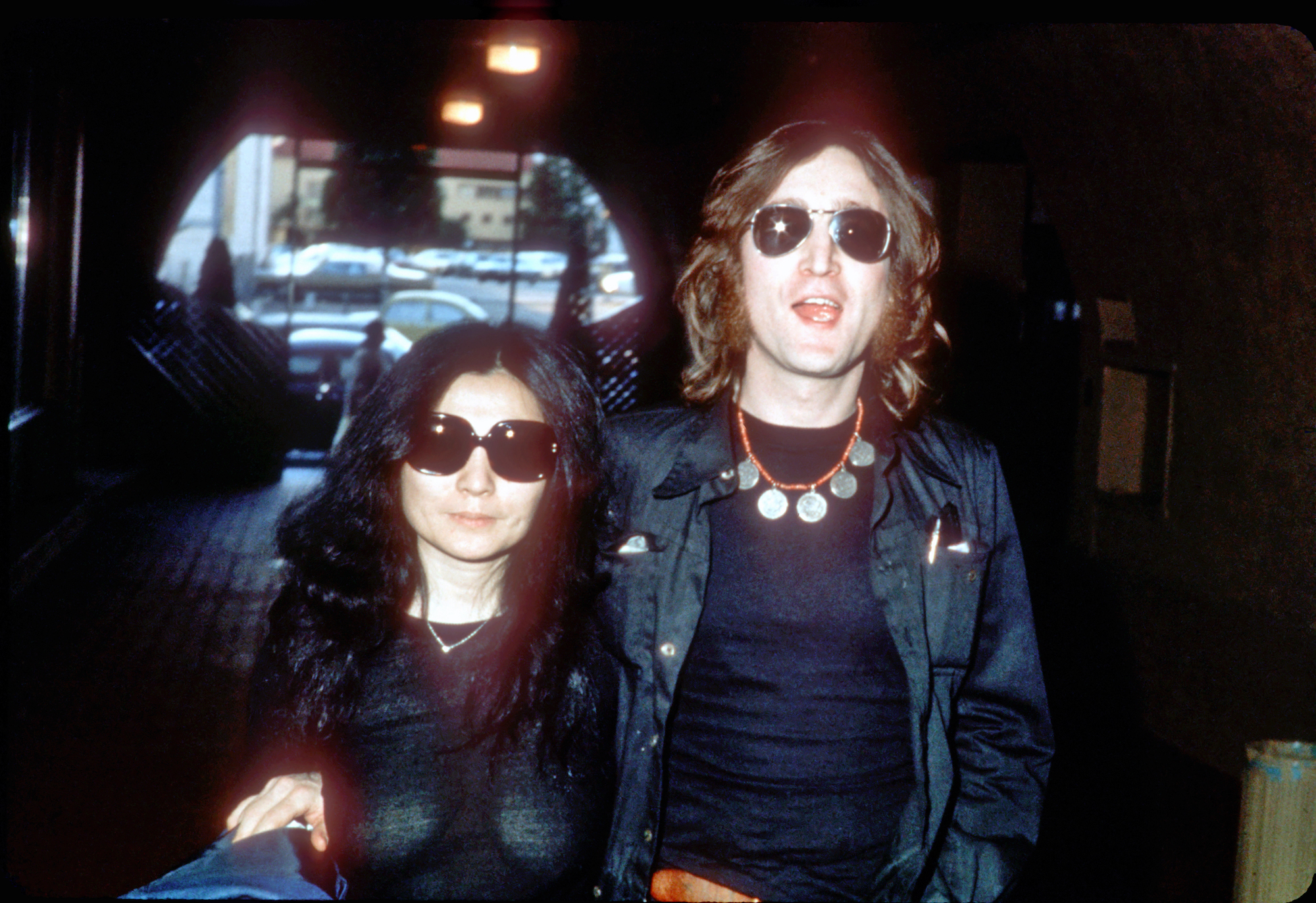

“I thought long and hard about this,” says producer Jack Douglas. “I asked myself, ‘Am I selling John out?’” Douglas is talking about his 2010 stripped-down remix of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s 1980 album, Double Fantasy.

The disc is part of the massive rollout of reissued Lennon solo material that EMI recently prepared to commemorate what would have been John Lennon’s 70th birthday on October 9, 2010, and the 30th anniversary of his death on December 8, 1980.

Double Fantasy was the last album Lennon released in his lifetime. It hit the streets about a month before his murder, a grim chronological juxtaposition that has always lent greater poignancy to the album’s songs.

Double Fantasy was meant to be Lennon’s “comeback” album, his return to the music business and public life after five years of retirement during which he had focused on the simple joys of domesticity and raising his son, Sean.

Instead, the album became Lennon’s farewell to a vast and adoring fan base, many of whom had admired him since the earliest days of Beatlemania.

It was Lennon’s widow, Yoko Ono, who asked Douglas to revisit Double Fantasy on the occasion of last year’s anniversaries.

“I got a call from her office asking if I’d be interested in doing something with Double Fantasy, not really knowing what,” says the producer. “I said yes. It shouldn’t be anybody else. I produced it. I pretty much knew where everything was on the master tapes.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

This left Douglas to decide what could or should be done with Lennon’s original masters.

“I realized it couldn’t be an ‘unplugged’ album,” he says. “If you unplugged all the electric instruments, there wouldn’t be anything left. And John’s original rough demos for the album were already in circulation, either illegally as bootlegs or legally in a box set [1998’s John Lennon Anthology]. So I thought the best thing to do was break it down to the original rhythm section that we recorded live in the studio, and just discard a lot of the overdubs and production.

“While the album holds up well, I thought it sounded like an Eighties production. And John was insecure about his vocals throughout his career, but particularly in this case, where he was coming back after a long time out of circulation.

“So, we had buried his vocals in the mix, double-tracked them, and I put a bunch of slap echo and reverb on them. But I realized that it would be really compelling to bring his vocals really up front – and Yoko’s too, although to a slightly lesser extent – so you really hear the emotion in John’s voice and feel what he was singing about. So far, people who have heard the mixes are stunned by how much you feel like you’re right in the room with him.”

But is this what Lennon would have wanted? That was the question Douglas struggled with. Was he indeed selling John out? In the end, the producer decided he wasn’t.

“I went back to John’s early solo work, when he first left the Beatles, the Plastic Ono Band stuff. And he didn’t mind pulling down his pants and being right up front at that point. That was because he was confident then, whereas he was just a little insecure when he did Double Fantasy, because he’d been away for a while. But in fact his voice was fantastic on that album, although I couldn’t convince him of that at the time. And now you get to hear it.”

So Douglas found himself returning to tracks he’d recorded 30 years ago. But by an eerie coincidence, he found himself transferring the original analog multitrack masters into the digital domain in the very same room where he’d last worked with Lennon, on the very last night of his life, completing a recording of Ono’s song Walking on Thin Ice. In 1980, that 10th-floor room at 321 W. 44th St. in Manhattan had been part of the Record Plant. Today, it’s a Sony transfer facility.

“They called me, and said, ‘We want to tell you something, Mr. Douglas. This is really strange. The very room where we do the transfers is rumored to be the last room you and John worked in the night he was assassinated.’ So in fact I was going to start this project in the very same room where I left it 30 years ago. The room was the same, and it was completely by accident.”

But, as a longtime believer in karma, astrology, and numerology, Yoko Ono might contend that such occurrences are no accidents.

“I didn’t even invite Yoko to these transfers,” Douglas says. “I thought that would be too upsetting for her. That was John’s last elevator ride that he took downstairs. It was all just way too much. And in fact, in the two weeks that we spent doing the transfers, it felt like John was a ghost in the room with me. It was very disturbing.”

The transfer process itself was painstakingly meticulous. Douglas originally recorded the album on two 16-track analog multitrack machines, synchronized via SMPTE time code.

These analog masters needed to be transferred to the Pro Tools digital platform at the highest possible sampling frequency, using the best A-to-D converters available.

First, however, the original analog tapes had to be taken from their secure storage area and baked at a carefully controlled temperature in order to re-adhere the oxide to the magnetic tape stock, a standard restoration process when working with older analog tapes.

“The tapes are held under lock and key at Studio One [Ono’s production company],” Douglas explains.

“They were taken from there to another facility, where they were baked, and then brought to us at the Sony transfer room. The masters would come in to us with an armed guard. We’d get four to six reels at a time to work on. The whole process took about two weeks. We took files of everything – outtakes, the works. And we brought it all to [engineer] Jay Messina’s facility, West End Studios.

“We started to analyze everything we had. At that point, John stopped being a ghost and became an active participant in this thing. He started to give us little clues of where we could find little gems – funny count-offs and pieces of comic business and one point where there was going to be a saxophone solo and John hummed the whole solo. So we took out the sax and put in the humming.”

Indeed, Lennon’s little snippets of banter between takes are one small treasure of Double Fantasy’s stripped remix.

At the outset of the album’s opening track, Lennon dedicates the song to his rock and roll heroes, “This one’s for Gene [Vincent], Eddie [Cochran], Elvis [Presley], and Buddy [Holly],” establishing the mood of nostalgia and romance that wafts throughout all of Lennon’s contributions to this musical dialog that he shared with Ono.

“Those fun bits of business totally reflect what the album was about,” Douglas says. “The original idea was that the album was a play that you were watching onstage, or onscreen as a film – a dialog between a man and a woman. And it occurred to me at this point that you could take that, bring it off the stage, and involve the audience in this dialog by making it very intimate, bringing John and Yoko into the room with you.”

John said, ‘We’re going to get blasted for this: John Lennon is not rocking anymore’

Jack Douglas

Neat chronological decimals mark Lennon’s life trajectory with eerie regularity. In 1960, at age 20, he first left his native Liverpool and landed in Hamburg to play the rough clubs of that city’s Reeperbahn red-light district with an embryonic incarnation of the Beatles. It was the start of a chapter in his life that would climax in the worldwide hysteria of Beatlemania.

Ten years later, Lennon celebrated his 30th birthday while recording his first solo album, The Plastic Ono Band, in 1970. He was glad the Beatles were now behind him and eager to commence another new chapter of his life. And in 1980, embarking on his 40th year of life, he completed Double Fantasy.

It was meant to herald the start of a triumphant third act for Lennon. His troubled youth behind him, reunited with Yoko after a mid-Seventies separation and drunken, desperate Lost Weekend, Lennon was now a contented father and family man. He saw this as a new beginning, although fate would soon transform it into a bittersweet denouement.

After a long silence, during a vacation in the Bahamas, Lennon suddenly came up with a batch of new songs that reflected where he was at that point in his life, his love for his wife and son, the rough times he’d been through, and the new equilibrium he had found. These songs would form the backbone of Double Fantasy.

“John wanted the album to be the sound of a 40-year-old man with a kid,” Douglas says. “He said, ‘We’re going to get blasted for this: John Lennon is not rocking anymore. But that’s what this record is. It’s about me now. And it’s made for my people. I want my contemporaries in the room to record it with me.’”

To co-produce the album, Lennon and Ono chose Douglas, who had helped engineer some overdubs on Lennon’s landmark Imagine album in 1971 and had since gone on to distinguish himself with outstanding rock albums by Cheap Trick and Aerosmith.

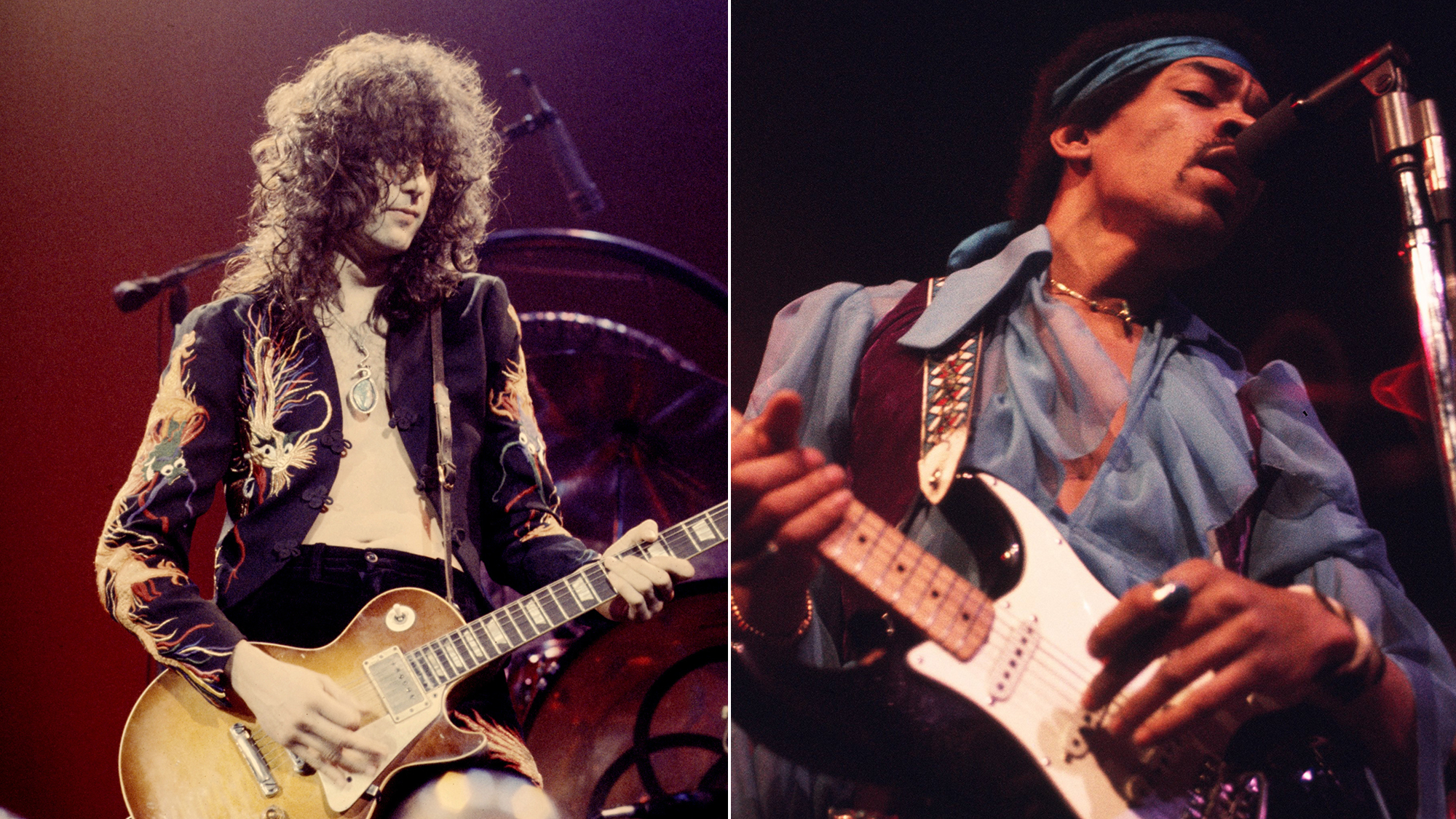

In keeping with Lennon’s wishes, Douglas recruited a top-drawer coterie of session musicians who were more or less in Lennon’s age group, including bassist Tony Levin, drummer Andy Newmark, and keyboardist George Small, along with a few players who’d worked with Lennon in the past. Percussionist Arthur Jenkins had played on the 1974 Lennon album, Walls and Bridges, while guitarist Hugh McCracken was a veteran of Lennon’s 1971 single, Happy Xmas (War Is Over).

McCracken has the added distinction of having played guitar with all four former Beatles. He’d previously played on Paul McCartney’s Ram album, in 1971.

“John said to Huey, ‘Love your work with Wings. Very good.’ Huey said, ‘Oh thank you, John.’ And John said, ‘You know, of course, that was just an audition to play with me.’”

Working from cassette demos Lennon had made in the Bahamas, Douglas put together some orchestrations with arranger Tony Davilio and began to rehearse the band without Lennon. In fact, Lennon was so uncertain about the whole project initially that Douglas wasn’t even allowed to tell the musicians the name of the artist on whose album they were working – although a few of the players soon guessed.

The cat was fully out of the bag when the location for the final rehearsal was announced – Lennon and Ono’s apartment at the Dakota building at 72nd Street and Central Park West in Manhattan.

At the very end of that rehearsal, as the musicians were walking out the door, Lennon suddenly announced that he had one last song idea.

He sat down at a Fender Rhoads electric piano near the door and played Just Like Starting Over, a song that would become the lead and keynote track for Double Fantasy, celebrating Lennon and Ono’s joyous reunion after the Lost Weekend separation period and the start of a new phase of musical and artistic collaboration together.

With sessions due to commence the very next day, Douglas opted to record this new song first, giving Lennon and the session players a chance to work spontaneously in the beginning, without pre-written charts or arrangements.

And he threw one more wild card into the band: guitarist Earl Slick, perhaps best known for his work with David Bowie. Slick had played on Bowie’s hit Fame, which had been co-written by Lennon, and on Bowie’s cover of Lennon’s song Across the Universe. Both tracks had appeared on Bowie’s 1975 album, Young Americans.

“I think John wanted me on his album because I was the street rock guy,” Slick says. “Everybody else in there could read music. They were session guys. I was the loose cannon.”

And so Slick turned up for the first day of recording at the Hit Factory on 48th Street, between 9th and 10th Avenues, unrehearsed and not sure what to expect. “I got there two hours early,” Slick recalls.

“Not that I was excited or anything! [laughs] Nobody’s there. I walk out of the control room into the main studio and John’s sitting in the middle of the room on a chair, playing his guitar.

“The gear wasn’t even set up yet. I went over and introduced myself, and he said ‘Good to see you again.’ I said, ‘Really? Have we met?’ He said, ‘Well, the Bowie thing.’ I said, ‘I think we recorded at different times.’ He said, ‘No, no. We were in there together.’

“We had this banter going on for about five minutes, and we were both laughing our asses off. Finally I said, ‘Look, let’s be straight here. You’re John Lennon, a Beatle! If I met you, I’m thinking I would remember that, unless I was so fuckin’ stoned.’ He goes, ‘Well that’s a possibility.’”

Slick vividly remembers his guitar and McCracken’s guitar contributions to Just Like Starting Over.

“I played the [rhythm guitar] chops that go with the snare drum, and Huey’s playing that low melody line. And in the bridge, there’s a slightly heavier guitar in there and that’s me.”

Playing guitar with Lennon was a treat for both Slick and McCracken.

“It was all pretty natural,” Slick recalls. “Things just fell into place. My rhythm style would have been closer to John’s, and Hugh had a lot more of the colorful nuances that would go rhythmically with what I did – because I played like John, very primal. And on solos, John would divvy up who he thought would be the best guy to play certain solos. Some of them were cut live. Like the solo on Cleanup Time that I played. That was on the rhythm track, and John just liked it, so he kept it.”

I brought a Les Paul and Hamer and a Fender Telecaster with a B-string bender on it. John had never seen one of those

Rick Nielsen

“John brought all of his guitars to the studio,” Douglas recalls. “Every Beatle guitar that you ever saw him with was in the room – his Rickenbacker 325, his Epiphone Casino… There were about 20 guitars in the room: beautiful old Strats, Les Pauls, 335s, and other things like that. But every time, John would end up using one of three guitars: a Gibson Hummingbird acoustic, Ovation acoustic, or this electric guitar called the Sardonyx.”

The Sardonyx, a curious footnote to electric guitar history, was a very sci-fi-looking custom instrument, with a pointy headstock that somewhat resembled a Flying V’s, and a squared-off body with pontoon-like metal appendages affixed to either side of the body. It looked a bit like a Star Trek–era spaceship or, in the words of Earl Slick, “like a fuckin’ ski rack for a car.”

Lennon’s affection for the instrument is very much a testimony to his restless quest for novelty. A man who’d quickly burned through LSD, Transcendental Meditation, heroin, and radical politics, he was easily bored and always looking for the next new toy, belief system, or lifestyle.

“The Sardonyx, Ovation, and Hummingbird all lived behind John’s bed at the Dakota,” Douglas remembers. “John could just reach behind the headboard and grab one of those. Those were the guitars he played when we were working on preproduction for the album, and he gravitated toward them in the studio as well.”

Most of Lennon’s electric guitar work for the album was played through a Fender Twin miked with a Sennheiser 421, Shure SM57, and Sony C30 in a triangular configuration. McCracken played a Strat, Gibson ES-335, and Les Paul, while Slick employed a Les Paul and 1965 Gibson SG Junior mainly through a late-Sixties 100-watt Marshall head and one 4x12 cabinet.

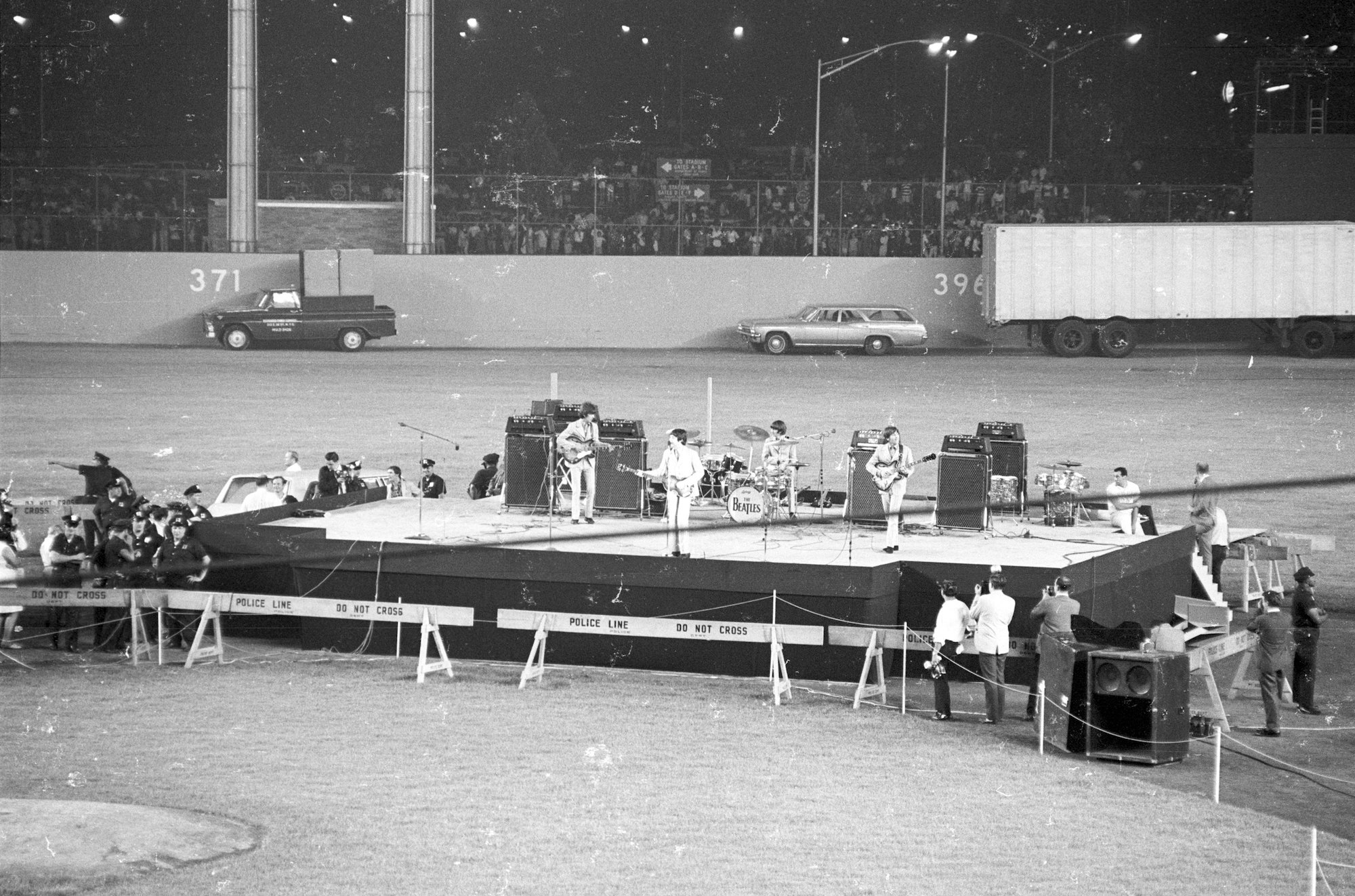

The sessions’ level of guitar geekery hit a new plateau when Rick Nielsen, Bun E. Carlos, and Tom Peterson of Cheap Trick came into the studio on August 12, 1980, to work on two songs for the album, Lennon’s I’m Losing You and Ono’s I’m Moving On. One of the world’s foremost guitar collectors, Nielsen was intrigued by the historical instruments Lennon had brought into the studio.

“I never called him ‘Mr. Lennon’ or anything,” Nielsen says. “It was ‘John.’ And we talked guitar stuff, gear. I got to the studio first. He comes walking in and says, ‘Oh, you!’ And I said back to him, ‘Oh, you!’ I think Jack had explained to him who we were.

“In 1980, Cheap Trick was pretty high on the charts. So it was just a musician-to-musician kind of thing. I brought a couple of my guitars, and John had his stuff. I was the first guy in America to have a Mellotron back in the Sixties, and John of course had his black, dual-keyboard Mellotron. So it was just gear talk.

“I brought a Les Paul and Hamer and a Fender Telecaster with a B-string bender on it. John had never seen one of those. So I ended up giving him that guitar. I was leaving for Japan the next day. I said, ‘Here, take it and try it out.’ I ended up getting it back three years after he was murdered. That was the guitar I used on the solo for Baby Loves to Rock [from Cheap Trick’s 1980 album, All Shook Up].”

Nielsen was somewhat horrified when Lennon opened up one of his guitar cases and brought out a Veleno, another one of his novelty instruments with a V-shaped headstock and mirrored-chrome body finish. Lennon seemed intent on using this guitar for his tracks with Cheap Trick.

“I said, ‘John, no. No. This is not right,’” Nielsen says with a laugh. “He had old, cruddy strings on it. But then he showed me his Rickenbacker 325, which I believe he’d played with the Beatles at Shea Stadium. It still had the song list scotch-taped to the side. I’m a guitar collector, so that was the coolest.”

Nielsen took some surreptitious measurements of the instrument’s short-scale neck and later had Hamer make a custom guitar for Lennon. Along with gear, fatherhood formed another bond between the two men.

Rick’s son Dax, his first child, was born on the very day the session took place. Nielsen had a hard time tearing himself away from his wife at this critical juncture in their lives together, but an opportunity to play and record with John Lennon was an honor that the guitarist couldn’t pass up.

“My standard joke is, had it been McCartney the answer would have been no,” Nielsen says, laughing.

Fatherhood was a big priority for Lennon at this point in his life, too. The birth of his son Sean some five years earlier had been a major factor in Lennon’s decision to retire from music from 1975 to 1980.

One of his first acts upon entering the Hit Factory to record Double Fantasy had been to tape a picture of Sean up over the console. Sessions generally had to end in time for Lennon to get home and tuck Sean into bed. Failing that, work would halt while Lennon made a good-night phone call to his son. Naturally, Lennon and Ono were enthusiastic in congratulating Nielsen on the birth of his first son.

“I’d flown in from Montreal and brought some Cuban cigars down with me,” Nielsen recalls. “So we lit them up and celebrated my son’s arrival. John and Jack, we were all smoking the Cuban cigars I’d brought in. Yoko had one, too.”

It’s somewhat surprising to hear of cigar smoke filling the control room during the Double Fantasy sessions. Most accounts of the dates stress the almost new-agey vibe of the sessions; all the players’ astrological charts had been checked in advance.

There was a “quiet room” and a shiatsu masseuse on hand. Tea and sushi, macrobiotic food, sunflower seeds, and raisins were on offer, but there was also junk food stashed in the studio maintenance room. There are also hints that cigars weren’t the only things being smoked in the control room.

I think he got a kick out of me because he was seeing a bit of himself in the old days and living vicariously through my dysfunction

Earl Slick

“It wasn’t as strict as all that,” Earl Slick confesses. “John would chain-smoke cigarettes, and I was drinking like a fish. And he put up with me, God bless him. I mean, I never got drunk enough not to play, but that was back in my pre-clean days. And I was a bad boy.

“I remember going out with [engineer] Lee DeCarlo pretty much every night after the sessions and getting stupid. John used to think it was quite funny when I’d crawl into the studio the next day after being out all night and fucked up. He’d just laugh and say, ‘You’ve had a night out!’ I think he got a kick out of me because he was seeing a bit of himself in the old days and living vicariously through my dysfunction.”

As it turned out, the Cheap Trick versions of I’m Losing You and I’m Moving On didn’t make it onto the album. Ono is generally credited with vetoing the tracks.

“She thought Cheap Trick were just some band I was trying to give a boost to,” Douglas says, “even though they’d been quite successful and were in the process of making an album with George Martin, ironically enough [All Shook Up].”

Accounts vary as to how the album version of I’m Losing You, with Slick and McCracken on guitars, was recorded.

Douglas remembers playing the Cheap Trick recording in the studio musician’s headphones and having them play along, in order to duplicate the feel. Slick and McCracken have no recollection of this, but Slick does recall Lennon’s unique approach to recording the guitar solo for the album version of I’m Losing You.

“John said, ‘Okay, Slickie, you’re going to come in with the first part of the solo and Huey the second, Slickie the third, and Huey the fourth.’ And once we laid our parts down, we tripled them, with each guy doubling the other guy’s stuff and adding harmonies over the top.

“As I recall, we had two small amps facing each other – little old Fenders, probably – with a stereo mic in the middle. John told us that that’s what he and George Harrison had done on Nowhere Man. And if you listen to that song, even though the tone on the Beatles track is a much more high-endy AC30 sound, you’re still gonna hear a similarity between those two solos and how they were done.

“Because there’s like six guitars on there, all very clean and very compressed, which is something I never would have thought of doing. I learned an awful lot from being in there with John.”

In 1998, the Cheap Trick recording of I’m Losing You was included on the John Lennon Anthology box set. The performance is certainly heavier than the version of the song on Double Fantasy, an approach that well suits the song’s edgy qualities.

Melodically somewhat reminiscent of the Beatles’ Glass Onion, the song features a lyric that seems like something from Lennon’s Lost Weekend period, but it was actually written during the same Bermuda vacation that yielded Lennon’s other songs for Double Fantasy. On his own in a strange place, without Ono, the notoriously insecure Lennon began to fear that Ono was slipping away from him one night when he couldn’t get her on the phone.

Ono’s answer song, I’m Moving On, seems to justify all his worst fears, with its repeated accusation, “you’re getting phony.”

It’s a moment you’ll find in any relationship. All couples have their ups and downs, and Double Fantasy captures the inner dynamic of one of the world’s most famous love relationships with the candor and honesty that characterizes most of Lennon and Ono’s work, individually and collectively.

Lennon got the album title from the name of a flower he’d seen at a botanical garden in Bermuda, and it became the work’s central metaphor. Double Fantasy is a glimpse into Lennon and Ono’s respective inner worlds. As much as the album celebrates the love that unites them, it also dramatizes just how different those two worlds were.

While Lennon was enjoying domestic bliss and tranquility during his retirement period, Ono had taken on the management of the couple’s funds, increasing their wealth substantially while secretly working her way through a relapse into heroin addiction.

Lennon’s Double Fantasy songs tend toward the romantic – lyrics filled with moonlight, angels, and tenderness, whereas Ono's lyrics tend to foreground cold, hard realities and the dark places of the mind.

Compare for instance Lennon’s Beautiful Boy with Ono’s Beautiful Boys. The Lennon song is gentle and reassuring, whereas the Ono track offers the quizzical cold comfort of lines like, “Don’t be afraid to go to hell and back,” set to ominously foreboding gunshot sounds in the background.

Once in a while one of us would start playing a Beatles song. And John would act like he hated it. But then he might join in

Earl Slick

Musically as well, Lennon and Ono are coming from very different places on Double Fantasy.

Lennon’s work is deeply steeped in musical nostalgia. From the Beatles’ 1968 White Album onward, Lennon became increasingly open about referencing his musical roots in Fifties rock and roll. He emerges on Double Fantasy as a man totally at ease with his own musical past, a 40-year-old guy who no longer cares if his tastes and preferences in music seem outdated.

With its piano triplets and somewhat schmaltzy chord progression, Starting Over offers frank homage to Fifties rock and roll balladry, a fact underlined by the stripped remix with its spoken dedication to “Gene, Eddie, Elvis, and Buddy.”

Woman fits comfortably alongside early Beatles-era Lennon ballads like If I Fell, a kinship that’s particularly apparent on John’s 12-string acoustic guitar demo of the song, included on the Lennon Anthology.

By contrast, Ono’s contributions to Double Fantasy are quintessentially Eighties sounding. Kiss Kiss Kiss wouldn’t be out of place on a Lene Lovich album, and Every Man Has a Woman Who Loves Him could be an outtake from a Blondie disc.

“My feeling was that she had to sound like that,” Douglas says. “She always seemed to be cutting edge. There is no retro in her book.”

“On Yoko’s stuff, I tended to use more pedals and effects,” Slick says. “Boss made this black auto-swell pedal that would make things almost sound backwards. No disrespect to Huey, but I think I might have done more of the weird, outside shit on Yoko’s stuff, because my brain was more wired that way. And that comes from working with Bowie.”

Lennon and Ono worked separately on their respective tracks much of the time, coming into the studio at different times of the day and night, although sometimes they worked together.

“When she was singing, John would be in the control room with Jack,” Nielsen recalls. “She’d be saying, ‘John, how should I do this?’ And he’d say, ‘Well, you do it this way, Mother.’ He called her ‘Mother.’ And they’d argue back and forth a little. She’d say, ‘Fuck you, John. Fuck you.’ Typical married couple.”

As part of Lennon’s mature level of comfort with his own musical past, he would sometimes reference a Beatles track while giving direction to the studio musicians. And he’d graciously accept it if one of the players couldn’t help playing a quote from some Beatles song or other – an inevitability in a roomful of musicians who all grew up loving the Beatles.

“You know what we’d do to the poor guy?” Slick rhetorically demands. “Once in a while one of us would start playing a Beatles song. And John would act like he hated it. But then he might join in. You can hear it on the box set from ’98. I think I’m playing She’s a Woman, which is a Paul song. And you can hear John in the background saying, ‘Who’s playing that? Stop playing that fucking song!’ But once in a while, he’d sit down and join us.

“You could get him going. If one of us started playing a Beatles song, he’d chime in for a verse or something like that. Then he’d say, ‘Okay, that’s enough of that.’”

Slick also slipped the riff from Bowie’s Fame into the outro of Cleanup Time.

“I’d never noticed that before,” Douglas says, “not until I did this remix. John would never stop reminding Slick that he [John] had cowritten what was Bowie’s only number-one hit at the time.”

The live dynamic of the sessions, with their sense of fun and interplay, comes across more clearly on Douglas’ stripped-down Double Fantasy remixes.

“John would be in his vocal booth when we’d do a take,” Slick recalls. “Once in a while he’d have a suggestion for a guitar part and say, ‘Huey, you cover this and Slickie, you cover that.’ But a lot of times we were left to our own devices.

“John picked everybody in there for what they could bring to the table, as opposed to dictating to us. That’s what I loved about working with both John and David Bowie. In the time I worked with them, what each of them wanted was Earl Slick. And that’s the proudest work I have in my entire discography, and I’ve got my name on a number of albums in my time.”

“Most of the vocals on the master track itself were the live vocals that John recorded in the room during the tracking,” Douglas says.

“There were only fixes if he sang the wrong lyric, wanted to change a lyric, sang off-mic, or just did something completely wrong. Because he was playing guitar at the same time he was singing, either an acoustic guitar, which you can hear on the live vocals, or an electric guitar with an amp in another room, and you can hear the pick running across the strings on the live vocal track. Which is kind of fun.”

Douglas captured Lennon’s voice with a Neumann U47 or U87 or a Telefunken 251; he tended to favor the 251. As the vocals went to tape, they were processed with a little compression from a UR EI LA -2A and a bit of Pultec EQ. For the original album release, Lennon doubled all his vocal parts, but Douglas left the overdubs off for the stripped remixes. The result is a more intimate vocal feel.

John being in the room was an unnerving experience. It was disturbing to Yoko. But she absolutely loved it

Jack Douglas

But that’s not all the stripped remixes accomplish. With the schmaltzy choir overdubs and dated-sounding Eighties signal processing removed, the songs themselves come more clearly into focus. And, almost magically, the contrast between Lennon’s material and Ono’s starts to soften.

Perhaps the new remix does an even better job than the original mix of realizing Lennon and Ono’s original vision. They show us how two very strong and distinctly different individuals could become as one in a love relationship. By clearing away aural clutter, the new mixes create a space where hopeless romanticism and hard-edged realism can indeed co-exist.

“Yoko helped a lot with these remixes,” Douglas says. “She’d come in every few days and listen to two or three mixes at a sitting. And she’d make some suggestions to us, which were all very good. Although she doesn’t speak in technical terms, she would notice little things.

“If I added a little Pultec high-end to the snare drum, she’d say, ‘All of a sudden the snare sounds like boof, boof, boof. Too much, too much. Too much Andy [Newmark].’ And it would just be a little bit of 10kHz on the snare. I’d say, ‘Okay.’ I’d totally respect her opinions, because she would hear every little thing we did.

“But mostly it brought her to tears. John being in the room was an unnerving experience. It was disturbing to her. But she absolutely loved it. I saw her the other night and she gave me a big hug and said she’s so thrilled with this.”

This feature originally appeared in the Holiday 2010 issue of Guitar World.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“It was tour, tour, tour. I had this moment where I was like, ‘What do I even want out of music?’”: Yvette Young’s fretboard wizardry was a wake-up call for modern guitar playing – but with her latest pivot, she’s making music to help emo kids go to sleep

“There are people who think it makes a big difference to the sound. Stevie always sounded the same whether it was rosewood or maple”: Jimmie Vaughan says your fretboard choice doesn’t matter – and SRV is his proof

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)