“Aqualung was Ian’s riff. The solo was all done on the fly. If I hadn’t got it in two takes then it would have been a flute solo. That’s when Jimmy Page came up to say hello”: Martin Barre on Jethro Tull, the Aqualung sessions – and supporting Hendrix

A signature-shifting collision of bucolic folk and frayed-edge rock, Jethro Tull’s Aqualung is one of the ’70s’ most daring records. Barre takes us on a deep dive back to those fabled sessions, from winging his parts to snubbing Jimmy Page

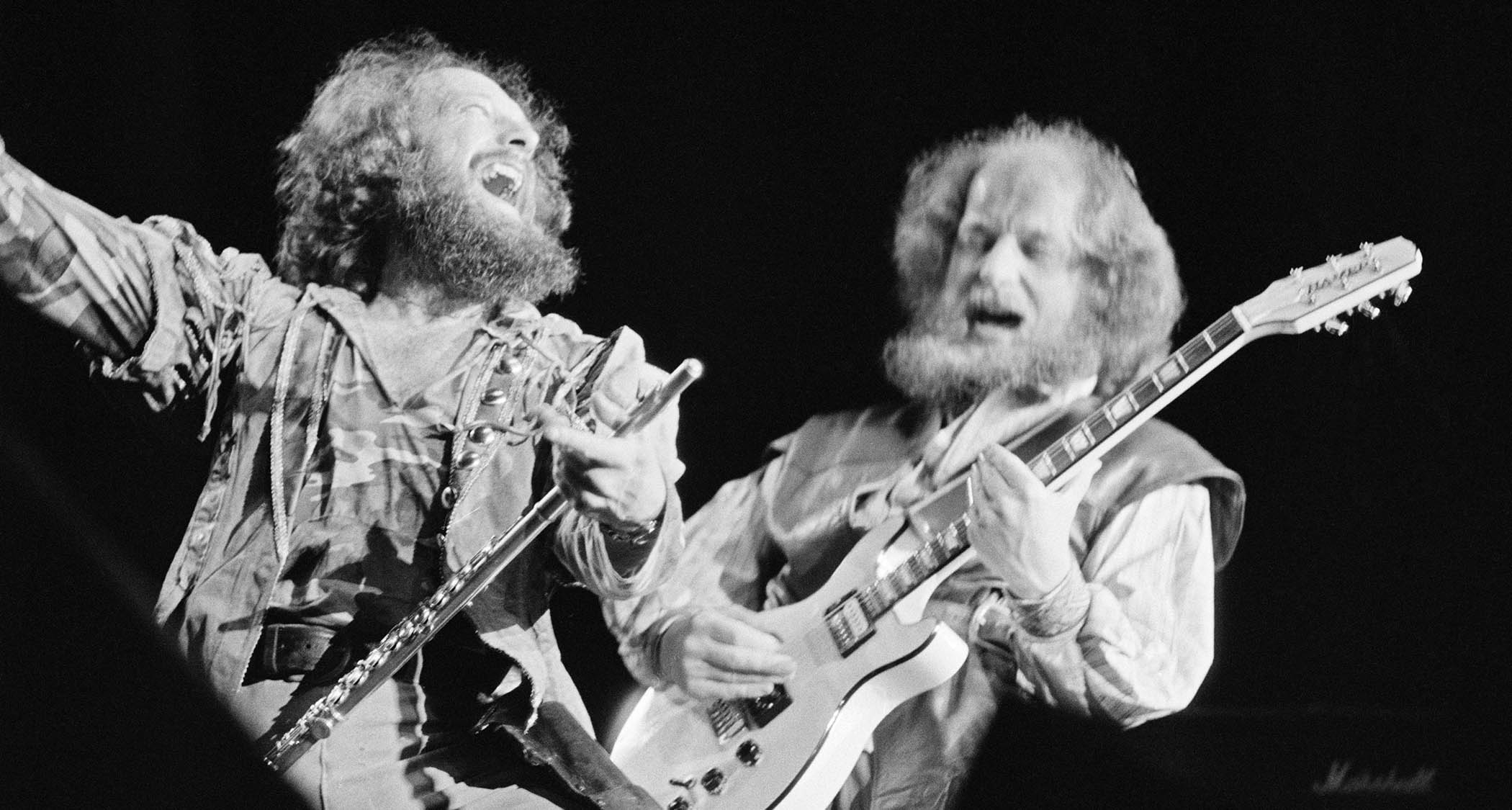

As Martin Barre reflects with a wry smile, the late ’60s were a glorious time to be a square peg. Formed in Blackpool as reluctant blues-boomers, under the de facto leadership of frontman Ian Anderson, Jethro Tull soon outgrew those roots, turning heads across London with their splice of classical, folk and chirruping flute.

Defying both the strictures of genre and the pleas of their record label, by 1971 the band had released Aqualung, the classic fourth album that stands as a monument to a time when artists, not their paymasters, held the creative reins.

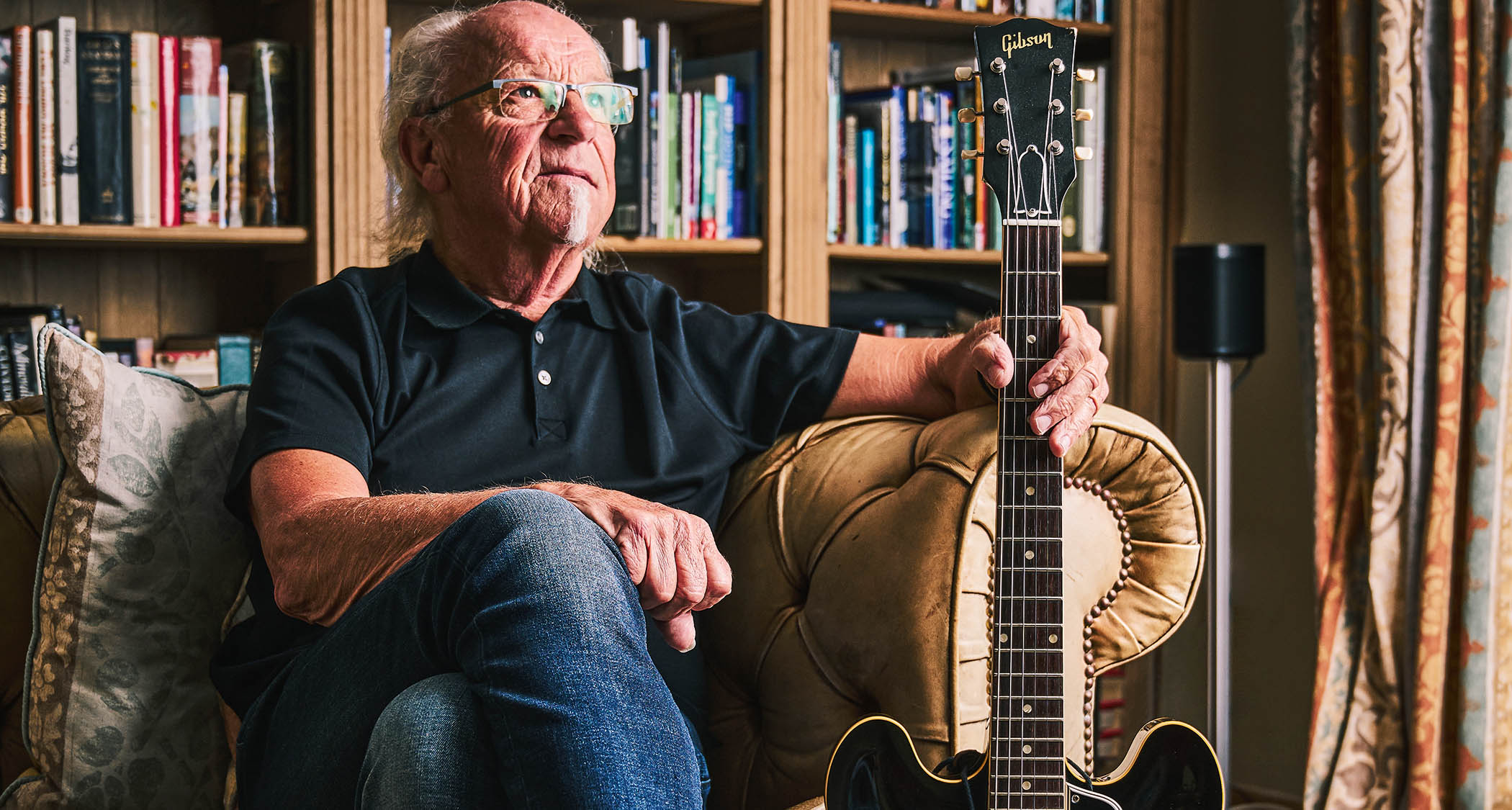

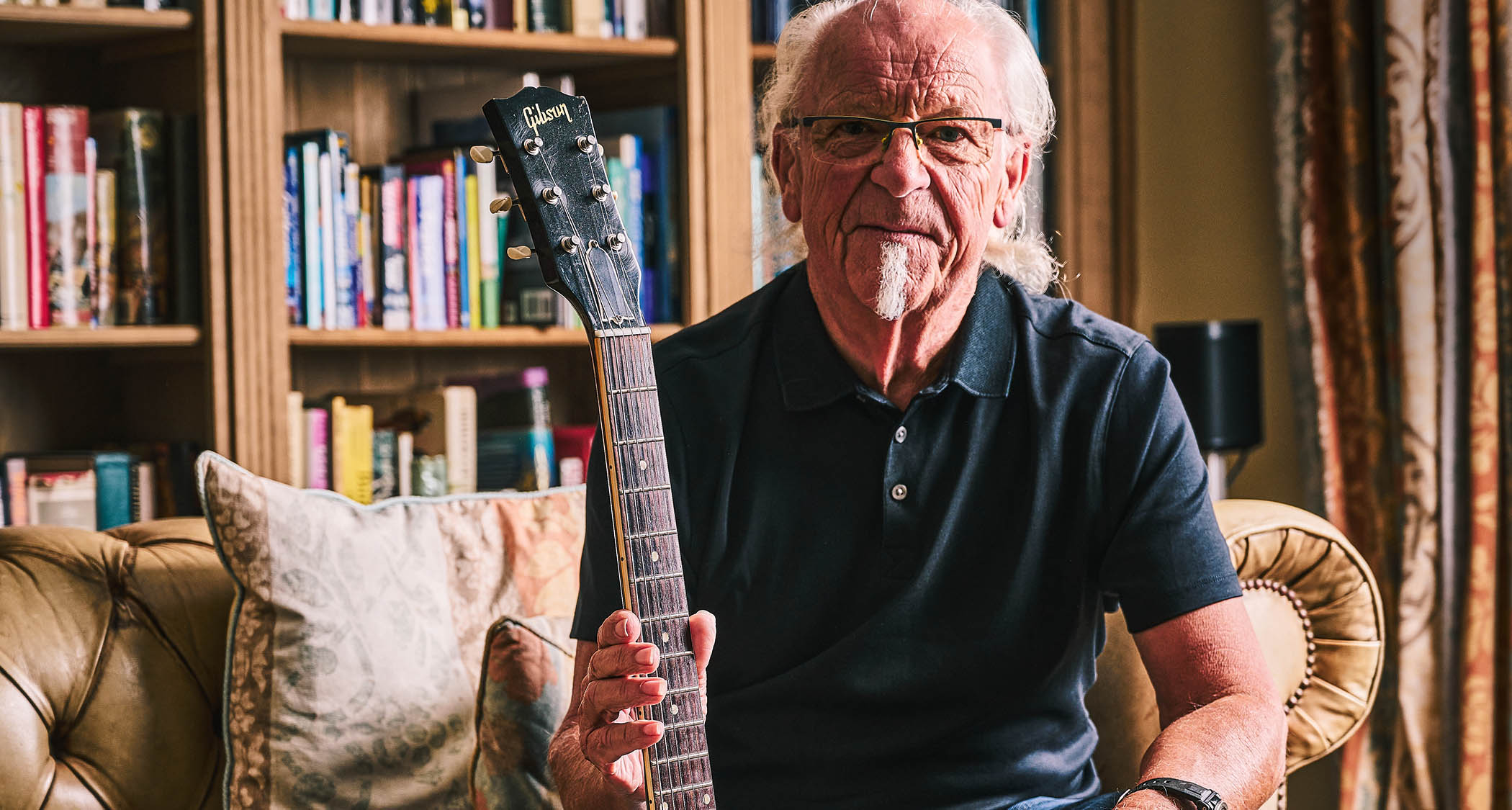

“We were lucky because we were left to our own devices,” considers the Birmingham-born guitarist, now a wry and tack-sharp 77 year-old who pulls each memory from Aqualung’s long-distant sessions as if it were yesterday.

“I don’t know if that will ever happen again. It was a whole different dynamic back then, a whole different game. I’m really proud of having been through that era, and survived it, and got so much from it.”

Where did Jethro Tull find yourselves when the band started work on Aqualung?

“Stand Up [1969, the follow-up to debut album, This Was] had been the breakthrough album, and then Benefit [1970] was a little easier, knowing we had the formula right. Coming back to England to record Aqualung after playing all around the world, we were road-toughened.

“So I would say the first three albums, we were just finding ourselves. I think Aqualung was the turning point where the music became intricate, more detailed, and needed more input from everybody. But like all albums, we didn’t know what was going to happen. It developed from nothing, from real basics.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

How were the band members feeling each other out at that point?

“I think we were all developing, learning how to play. We certainly were during Stand Up and Benefit. The music was so naive in those days, and you listen to the original recordings and go, ‘Whoa, I could play that solo a lot better now.’ But that’s not the point. It’s a little moment in history and it’s important it stays that way, with all the crunches and beeps.

“We were just finding our way through music. Jeffrey [Hammond] joined the band for Aqualung – and when I met him, he didn’t know which end of the guitar you picked up. He literally had never played an instrument in his life. So me and Ian taught him to play bass while we were learning these songs.”

Despite that, the whole band sounds so locked in on the Aqualung recording.

“To me, that’s what music is about. There’s sympathetic interaction and that was always part of our makeup. There were no stars in Jethro Tull. I mean, Ian was the frontman – but, musically, there was nobody imposing their attitude at all. There was room for everybody. That’s what music is. And if you don’t do that, it shows.”

The title track is such a great guitar moment. There’s that ominous six-note intro riff, then your solo…

“Well, it was Ian’s riff. The solo was all done on the fly. I think it was take two – and if I hadn’t got it in two then it would have been a flute solo. But that’s when Jimmy Page, who was recording with Led Zeppelin in the basement of Basing Street Studios, came up to say hello.

“He was in the control room window, waving madly. I was in the middle of the solo, and I thought, ‘Sorry, but I can’t stop.’ And I didn’t. I just turned my back. Which was a bit rude. But that was the solo on Aqualung.”

The lead playing on the track Cross-Eyed Mary is really striking, too.

“It’s music that other bands don’t play, and the chords are sort of oddball, they’re not quite predictable. It’s simple – but it isn’t.”

Another iconic moment is the intro to Locomotive Breath, with the dance between piano and guitar. How did that unfold?

“Nothing was planned. John [Evan, piano] had written that introduction, some really nice chords and voicings in there. I just played pentatonic blues, squeezing in phrases where there was space. Me and John recorded that live.”

And the solo on My God is another highlight.

“Well, all these things happened in a couple of takes. There wasn’t the luxury of doing 30 takes or changing a note or whatever. Which is why they’re never perfect, but they’re full of enthusiasm.

You know the structure and chords, and you know you’ve got to acknowledge the changes, but sometimes you just hear the notes and go for it

“Even when I record now, that energy starts diminishing. I like that freshness, that excitement. Maybe, again, it’s naivety – you’re not quite sure where you’re going to go. You know the structure and chords, and you know you’ve got to acknowledge the changes, but sometimes you just hear the notes and go for it. I think it was Steve Vai who said, ‘Go where your ear tells you.’”

Tull always had non-standard time signatures.

“[Laughs] That’s one way of putting it! ‘Stupid’, ‘crazy’, ‘pointless’, ‘why?’ I think we just made it like that so people could not dance to it, ever. To me, all the Tull stuff comes naturally: you could conjure up a song off Songs From The Wood [1977] or Heavy Horses [1978], and I can probably play it. And within a half an hour, I can play anything because I can remember what I did.

“But in my band now, they’ll learn the music at home – it’s like their homework. We might have an afternoon’s rehearsal before the first show, we’ll run all the songs and they’re like, ‘This music is a nightmare, it’s so difficult.’ I guess that passes me by. To me, it’s normal.”

What had inspired you as a guitar player, before you joined Tull?

“Just everything. I left uni and joined this soul band in Bognor Regis – the only way I could get in was playing saxophone. Then we went to R&B, Tamla – we changed as the musical tastes dictated, just to get work.

“Until the Blues Train hit England. All these amazing artists – Buddy Guy, Freddie King, Sister Rosetta Tharpe – they’d get out of the train and play, every week on TV. It hit like a ton of bricks. That was what opened the door for the blues boom, but it’s not what I wanted to do.

“All the guitar players in the UK, they were playing Albert King and BB King licks but really badly, and I thought, ‘I don’t want to be one of those.’ I acknowledged it, soaked it in, but wanted to do something different. So I was listening to jazz, classical, blues. And that’s been Tull’s ticket, really. We just listen to everything.”

What do you remember about your earliest days in Tull?

“They’d taken a huge plunge into the unknown getting me onboard as a guitar player. Tull were a blues band and Ian didn’t see that going the distance. He was quite clever, looking ahead with the music. So he took a big risk having me there.

“When I started back in 1969, I was truly terrified because in the first few months I was on the same stage as every one of my heroes: Mike Bloomfield, Jeff Beck, Jimi Hendrix. I was really in at the deep end. So I see those first years as building up an identity. I wouldn’t have called myself a musician until quite a way down the line.”

What was the setup in the Basing Street Studios while you were making Aqualung?

“I would say that 80 per cent was live, then me and Ian added some overdubs. I remember the solo in Hymn 43. Terry Ellis [producer] came in and wanted to be part of the music. And we didn’t want him to be because we were quite insular and didn’t need any outside information.

“There was a horrible moment: I’d recorded a solo for Hymn 43 and Terry didn’t like it. He said, ‘I think you should do another one.’ I said, ‘No, I’m happy with that.’ So I had to go around everybody and ask, ‘What do you think?’ They all voted for it, so it stayed. But it was uncomfortable.”

With a band, there’s always the question of how much outside guidance you need?

“Well, with Jethro Tull, you don’t need anything at all. It sounds glib and pretentious if we say, ‘We know what we’re doing.’ We probably don’t – but we know what we want. And the only times we had outside interference, it went wrong.

“We did a Christmas song in 7/4 – Ring Out, Solstice Bells – and the record company said, ‘It’s got to be in 4/4.’ So we got a producer in to record it in 4/4. It was horrible. We didn’t want to be there. The poor guy knew we didn’t want to be there. The song sounded stupid. You know, you can’t add a beat to every bar to music that’s already written. In the end, it was released in 7/4.

“The other time, I think we were having a dip in sales and this record company whizz-kid turned up in the studio with a pile of albums: ‘I want you to listen to these.’ One was Fleetwood Mac, The Moody Blues, maybe the Eagles. He said, ‘These are the top-selling albums of the year. Go and listen to them – that’s what I want from you.’

“No. That’s not how it works. Maybe with selling cornflakes, but that’s not how it works with music. The independence in Jethro Tull has been vital. And we’ve kept it throughout all these years.”

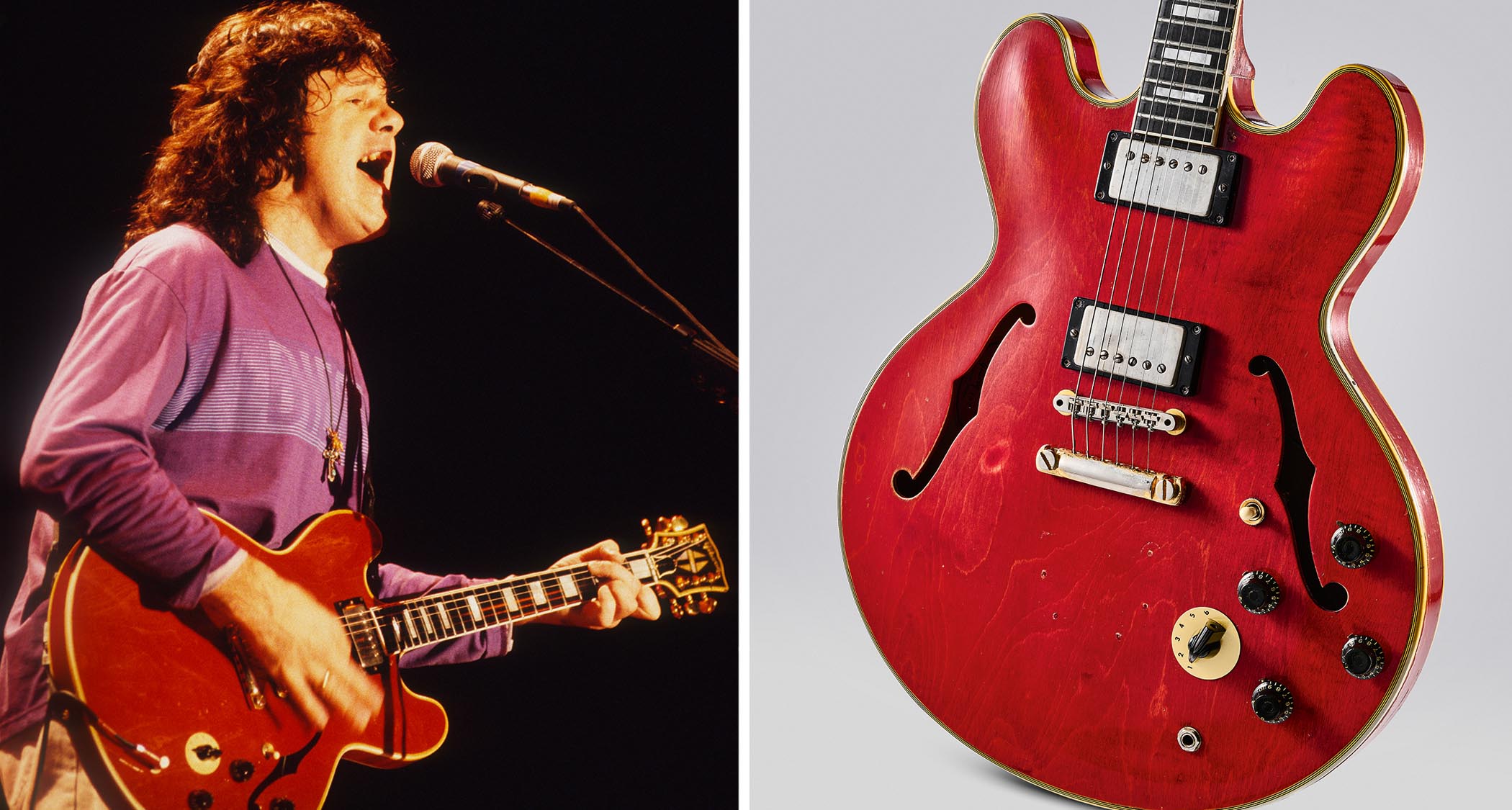

What was in your arsenal of guitars during the Aqualung period?

“Not much of an arsenal [laughs]. I’d met Leslie West after Benefit. We’d toured America with Mountain as our support band and I ended up buying a Les Paul Junior, like everyone else who met him did. I had a really old ropey Fender Strat, but basically it was all recorded on the Les Paul Junior.

“For amps, it was a Hiwatt with this horrible treble booster: when you looked inside, it was just a couple of capacitors and wires. But the Hiwatts didn’t have that front-end overdrive, so it needed a bit of a kick. For Cross-Eyed Mary, I used this tiny little amp that I bought for £2 off a guy in Birmingham. It doesn’t even have a make on it, but it just sounds like nothing else. And I had a Fender Super that I used for My God.”

As your career in Tull went on, did you get the chance on the road to find guitars?

“Well, they found us. There were these college kids who’d follow all the bands around. They’d go around the pawn shops and bring a selection of vintage guitars to sell. Paul Hamer was one, when he was just a kid, who was almost annoying. He’d turn up at the stage door and you’d be like, ‘Go on then, show it to me, but I’ve only got 10 minutes.’

“I was quite offhand with him, but our relationship developed and now we’re best friends. They’d bring sunbursts, old Strats – you could buy anything. On the other hand, most players would only have two or three guitars because that’s all you could play on a gig. Having a ‘collection’ was, like, ‘Why?’”

You play Soldano tube amps these days. When did that relationship start?

“Thirty years ago, at least. I used Hiwatts in the first few years, then went to Marshalls because they had better overdrive. No effects, just straight in. The Marshalls didn’t survive very well in America – they often blew up, God bless ’em.

The Gibsons and Fenders, the mandolins, bouzoukis, mandolas and all the others, they add to your arsenal of sound. But essentially, the core of what I do is the PRS

“I had about 10 of them and at any one time, two might be working and the rest our boffin had in pieces backstage. But Soldanos became [my choice]. The reliability, the sound, they just work for me, in every possible way. I love them to bits.”

In your music-making today, which guitars are the touchstones for you?

“Well, the tools of my trade would be the Soldano and the PRS. I went through lots of different manufacturers: Hamer, Manson, Ibanez, Fender – I had a relationship with all the builders.

“But PRS, I bought them and they were just so reliable. They just do exactly what you want them to do, every night, no deviation. And in the end, I just wanted to turn up at the gig, fire up the amp, plug in the guitar – ‘Okay, what time do we start?’ The Gibsons and Fenders, the mandolins, bouzoukis, mandolas and all the others, they add to your arsenal of sound. But essentially, the core of what I do is the PRS.”

Some guitarists specialise in just one discipline, but you’ve always seemed interested in every aspect of music. How did that come about?

“Yeah, I like to write music on mandolin, acoustic, electric – you’re going through a different door to get where you want to go. It’s that ‘jack of all trades’ thing. I’m never going to be the whizz-kid guitar player, but I don’t really want to be.

“I always think George Harrison is such a great musician and he’s my role model: tasteful, melodic, great songwriter, great band member. That’s what I take pleasure in. In some of my other projects, I like sitting at the back and being part of an ensemble.

“There’s a lot more in music than being tied to one direction. I play two or three hours every day. I don’t even count. But I diversify. So I play electric for an hour. Then I play my flute for an hour. I think music has a lot to offer, in different colours. What’s next? I want to record a new solo album. I want to get back on the road as an electric band. I love playing. I love performing. It’s almost an addiction.”

You sound like you’re still reaching for something?

I hate myself sometimes. I play and I go, ‘That was really awful.’ And that’s the reality of music. Perfection doesn’t exist

“It’s an infinite thing, music. I’ll never stop learning. I’ll never stop being inspired. I never, ever think I’m good enough. You know, I hate myself sometimes. I play and I go, ‘That was really awful.’ And that’s the reality of music. Perfection doesn’t exist. And I’m sure it doesn’t even for the players where you think, ‘Wow, they’re amazing.’ I’m sure they torment themselves, wanting to play better and improve.”

Looking back on Aqualung, where do you place it within your body of work?

“I recognise its importance. At the time, it wasn’t fun to make because we had problems with the performance. We struggled with the studio breaking down. So we didn’t finish the album and go, ‘Well done, guys. Let’s go round the pub.’ It wasn’t a feel-good album.

“But whatever that formula was – Ian’s great songs, the lyrics, the dynamics of having acoustic songs and electric songs – that sort of kickstarted our ability to switch from one extreme to another. In retrospect, it’s a really important album, but we didn’t intend it to be.”

- Acqualung is out now via Rhino/Parlophone.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.