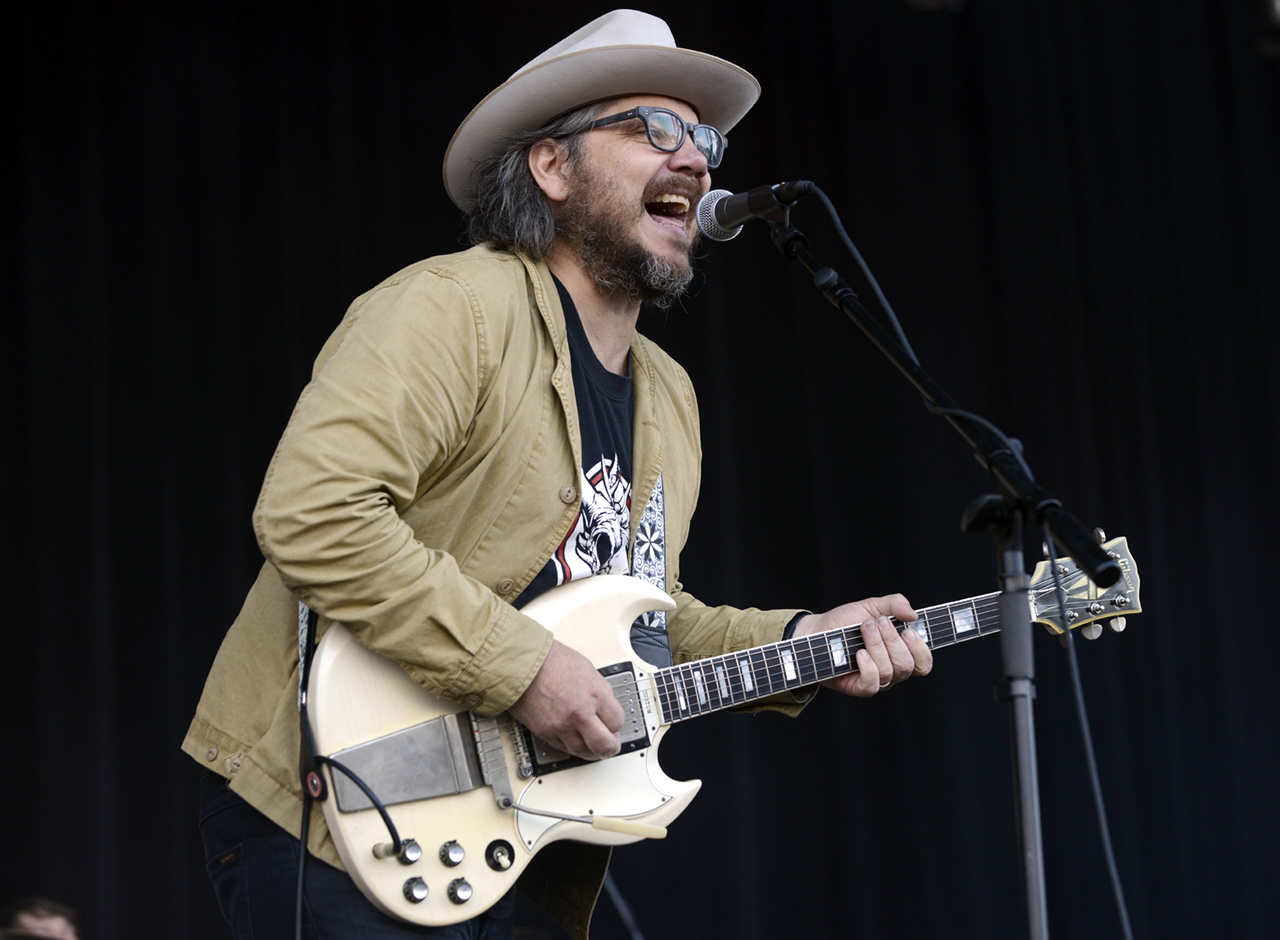

“I remember it being very uncomfortable. My body would just vibrate with anxious energy listening back”: When their lead guitarist was fired, Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy had to step up to the plate. The result was an iconic record with a “panic attack” solo

Tweedy recalls 2004’s A Ghost is Born as a crash course in taking over lead guitar, as he breaks down his attitude to songwriting, explains why the best artists are experts in failure – and suggests modern players might be too good to be remembered

Released in 2004, A Ghost is Born marked a sonic departure from Wilco’s classic fourth LP, Yankee Hotel Foxtrot. The change was shaped, in part, by necessity – with the departure of multi-instrumentalist Jay Bennett, singer and rhythm guitarist Jeff Tweedy found himself assuming the role of lead guitar player.

It was the first time listeners heard Tweedy speak so openly with his guitar. His leads – raw, unpredictable and deeply emotive – added another dimension to the sound that had already earned Wilco a dedicated following.

Earlier this month the band marked 20 years of A Ghost Is Born with a vinyl repress and a nine-disc deluxe box set. We caught up with Tweedy to discuss the making of the record, his transition to lead guitar, and knowing when a song is finished.

How did Jay Bennett’s departure impact you as a guitarist?

“The chronology is important – he was dismissed during Yankee Hotel Foxtrot and he was out of the band for a good few months before the record was finished, and then we toured after that record as a four-piece, primarily. That's when I was confronted with the idea that I needed to play lead guitar. I kind of fell in love with giving myself permission to speak with the instrument.”

Before that, what experience did you have playing lead in a band?

“None. I had played some leads on songs like I’m The Man Who Loves You, and maybe a bit more than people realize on different records. I would play leads on the recordings – but as far as being a lead guitarist live, it was never a fully embraced role.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Why didn’t you play leads live?

“My focus has always been putting a song across: singing and being a part of the rhythm section. I started as a bass player in Uncle Tupelo, so I’m most comfortable holding that down.

“I’ve always been kind of amazed at guitar players in trios that can take off into a solo and not lose the momentum that the rhythm playing contributes. It’s a really unique thing to make that work. If it’s not done well, it just becomes a mess when the guitar player stops playing the rhythm.”

So it wasn't an aspiration; it was more, “There’s nobody else to do this; I guess I have to”?

“Maybe it became more of an aspiration. I’m just saying, my first inspirations as a musician were more based around the power of song and the desire to participate in that kind of connection.”

How did Jim O’Rourke influence your playing on A Ghost Is Born?

“He never really told me how to play or what to play. The biggest contribution I think he made was the encouragement of having a musician I deeply admired being so accepting of my lack of technique – or an individual technique. That meant a lot to me.

I just think how silly it would be to ask Hubert Sumlin to play like Eddie Van Halen

“Having somebody say, ‘No, it really sounds good,’ I felt like I was doing something that felt true and honest to myself. I knew that wouldn’t necessarily translate to the rest of the world; but it didn’t matter because I had one person on my side.

Sometimes that’s all you really need.

“That’s all you really ever have. It’s all one person at a time. An audience doesn’t really make any sense. – it’s just a concept. A person liking it is deeply important.

“Anybody that gives themselves permission to play the guitar the way they feel isn't going to sound exactly like anybody else. I think a lot of modern playing has been distracted by people being able to master a lot of different styles. I just think how silly it would be to ask Hubert Sumlin to play like Eddie Van Halen.

“All the best players – all the players we care about –wouldn’t fit the modern paradigm of Instagram or TikTok. They were people that had a voice. I think that's a worthwhile aspiration.”

Did krautrock bands like Neu! influence A Ghost Is Born?

“The cosmic drone music coming out of Germany during the ‘70s was really important to me. It was exciting to start to incorporate some of those rhythms, in particular, into the band. I’d listened to those records and sing over them, and I’d think, ‘God, it would be cool if there was a song here.’

“They’re much more disciplined than the way we implemented it. I think Neu!’s music is a super-tight philosophical endeavor. Like, ‘We don't deserve another chord. We’re gonna do two albums before we give ourselves another chord.’

“The rhythm felt like a really unique and sturdy backdrop for my folk songs and simple chord structures. Most of the songs I write fall into that category. I generate a lot of songs that are pretty simple, so that part fit pretty quickly. In the box set, on Spiders, you’ll hear it has a lot of melodic content in terms of how the chord structure goes.

“At some point I just started doing that with all my songs. ‘Can I just sing this melody over a drone? How many of those chords are necessary to get the melody across?’ In the case of Spiders [(Kidsmoke)] it was like: ‘Hardly any.’”

I’ve learned to value that feeling of being exposed as an indicator of being on the right path

How do you know when a song is done?

“I don’t know how you know. I know that at some point you get comfortable with presenting it to the world. In Wilco, the initial impulse of a song is usually pretty close – but that just feels like what we do.

“Then there’s an impulse to take it apart and see if there’s a way to do it that isn't exactly what we do. Wilco has, for a long time, been interested in finding out what sounds like us by not doing what comes first.

“That being said, a lot of times it feels good to just go with that initial impulse. Cruel Country was just one or two takes of every song, because once everybody heard the song and knew the chords, it was understandable.

“Then everything is kind of the opposite on a record like Cousin. ‘We know how it goes, so what other potential is there to discover something inside of us?Something that feels new and worth sharing.’ It’s been a toggling back and forth with those two impulses for as long as I’ve been making music.”

Is the solo in At Least That’s What You Said meant to emulate a panic attack?

“I think that it fits – and I certainly was having a ton of panic attacks at that time. But I can’t honestly say that that was the intent. I just think it is a panic attack.”

What were your thoughts when you heard the playback of that solo?

“I remember it being very uncomfortable. My body would just kind of vibrate with anxious energy listening back. It wasn’t a particularly pleasant experience – and that’s not unique to that record, to be honest.

“I’ve kind of learned to value that feeling of being exposed as being an indicator of being on the right path. I think you should get to some level of discomfort – that means you’re sharing something that maybe your body’s trying to hide.”

What gear experiments would you say defined the sessions?

“I think that there were experiments with getting instruments to kind of play themselves, or allowing the different electronic techniques of setting up an instrument to just kind of perpetuate itself. A fan or a delay loop – things like with different gadgets so you could walk out the room and still have the sounds evolving.

Every artist should strive towards the notion that there’s nothing they could do that would have no value

“Those were probably the most prominent experiments. Overall, it was an atmosphere of welcoming your own technique; just individual self expression as opposed to musical prowess.”

Did anything not work while making the record?

“I don’t think that was the mindset. I think the notion of failure in art is something you need to get over. All the works of art that matter are the ones where you can’t picture the artist failing – there’s almost nothing they could do that would have been considered a failure.

“They don’t have to play the right notes; they don’t have to move the right way; there’s no context where the notion of failure makes any sense. That’s what I’m striving for, always. I think every artist should strive towards the notion that there’s nothing they could do that would have no value.

“I think artists are experts at failing – that’s maybe the most valuable part of presenting yourself to the world. In the age of AI, failure is getting more valuable by the second. Fallibility is the beauty of it; I don't think a machine is going to be taught to fuck up in the same way six people in a room together can.”

So is failure a success?

“I wouldn't say that. I just think that the point of art has to transcend the execution of it. It should feel like a loved one trying to express themselves to you and not having the exact words – but you knowing what it means; knowing what they're trying to say. That, to me, is rock ’n’ roll.”

- The 20th anniversary editions of A Ghost Is Born are out now.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“I suppose I felt that I deserved it for the amount of seriousness that I’d put into it. My head was huge!” “Clapton is God” graffiti made him a guitar legend when he was barely 20 – he says he was far from uncomfortable with the adulation at the time

“I was in a frenzy about it being trapped and burnt up. I knew I'd never be able to replace it”: After being pulled from the wreckage of a car crash, John Sykes ran back to his burning vehicle to save his beloved '76 Les Paul