“I turned up at George Martin’s office with a diabolically bad demo – but he could see there was something there”: How Jeff Beck’s Blow by Blow triumphed against the odds to change instrumental guitar forever

50 years on, Blow by Blow remains an inspirational force – a turning point for Beck and guitar-led music in general

Jeff Beck’s Blow by Blow shouldn’t have been a success. By all accounts, it was a huge risk, even in the heady, more musically adventurous era of the mid-’70s. It was an instrumental album – an instrumental jazz album.

Perhaps oddest of all, it was an instrumental jazz album by a rock guitarist, which meant that it ran a highly possible risk of alienating rock and jazz audiences alike. And even though Epic Records released separate singles of three songs from the album in Japan, the U.K. and the U.S., none of the songs became hits.

Yet audiences in the United States, United Kingdom and beyond enthusiastically embraced Blow by Blow. It peaked at a remarkable Number 4 on the Billboard 200 album chart and earned Platinum certification, outselling every single album Beck previously released with the Jeff Beck Group and Beck, Bogert & Appice, which all managed to go Gold. In fact, Blow by Blow (along with its similar follow-up, Wired) remains the best-selling album of Beck’s entire career.

However, the success of Blow by Blow was much wider reaching than mere chart positions and album sales figures. Beck’s bold move opened up new possibilities for jazz and progressive guitarists like Al Di Meola, Allan Holdsworth and numerous other musicians to release albums that appealed to jazz and rock fans alike.

It also helped spark the instrumental shred guitar phenomenon that started a few years later in the early ’80s by proving that there was indeed a relatively sizable potential audience for instrumental guitar music.

Its success even had a profound effect on Beck himself, giving him a sense of direction that influenced his remaining career by encouraging him to rely on his inner muse.

In celebration of the 50th anniversary of Blow by Blow, we’re taking a look back at the history of this revolutionary album that changed the path and popularity of the electric guitar in a highly profound way.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

From blues to funk

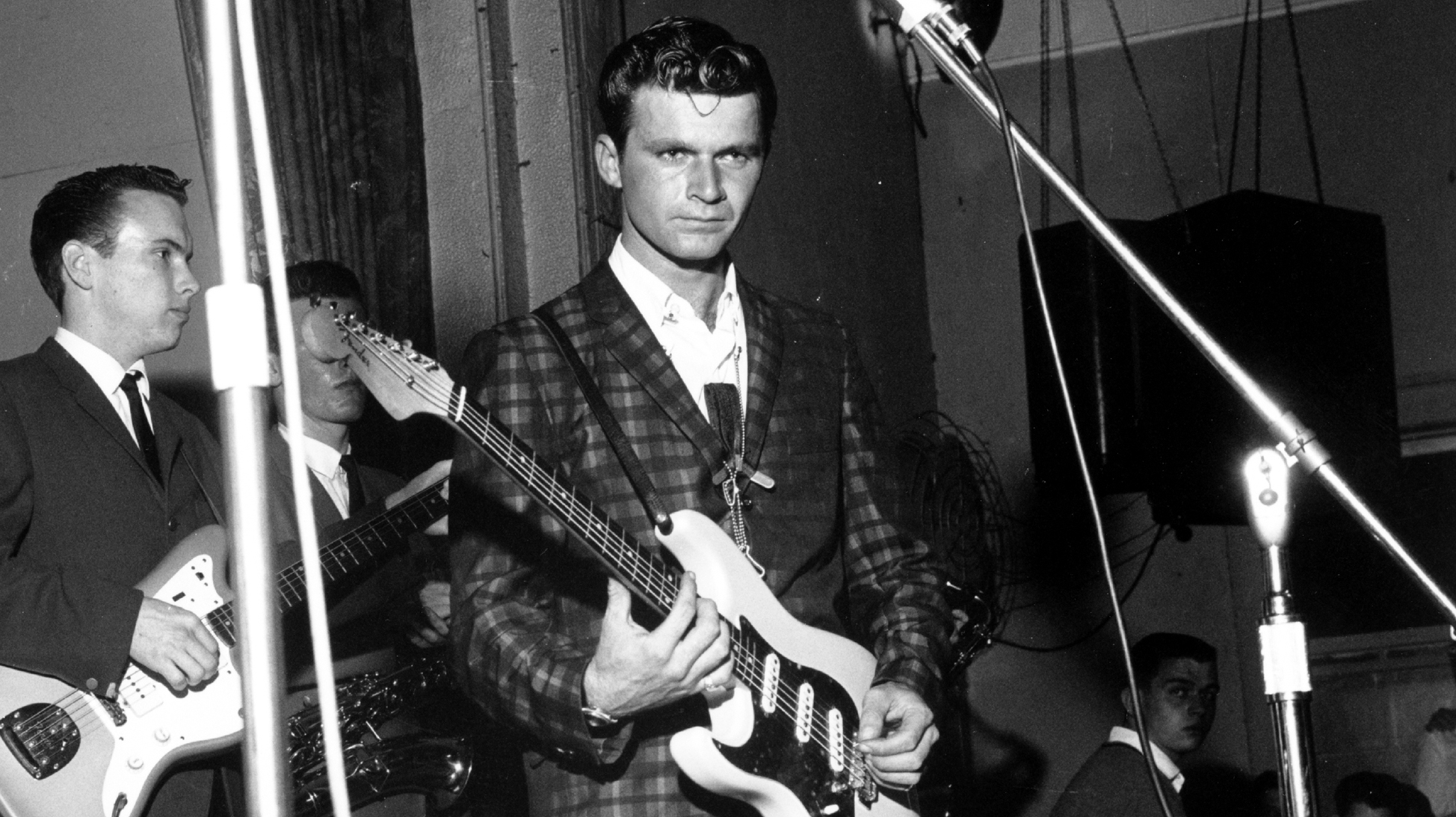

During the early ’70s, Jeff Beck had earned a reputation as being difficult to work with that was not entirely undeserved. Ever since being fired from the Yardbirds in November 1966, Beck seemed unable or unwilling to settle into any particular musical direction for a prolonged period of time.

When Beck first put together the Jeff Beck Group with singer Rod Stewart in 1967, he went through a staggering variety of bass players and drummers before settling upon Ronnie Wood on bass and Micky Waller on drums just prior to recording their first album, 1968’s Truth.

However, Waller was gone by the second album (1969’s Beck-Ola), and by the third Jeff Beck Group album the guitarist was accompanied by an entirely different lineup as Beck shifted from a hard rock/blues focus to a more funk and R&B-inspired sound.

That second lineup managed to last two albums (Rough & Ready, Jeff Beck Group) before Beck threw in the towel during the summer of 1972. Retaining only keyboardist Max Middleton, Beck started a new lineup with Tim Bogert on bass and vocals and Carmine Appice on drums.

This eventually became the hard blues-rock power trio Beck, Bogert & Appice, but that band was also short-lived and broke up in early 1974 after releasing one studio album and a live album released in Japan.

In an interview with Classic Rock, Appice said, “Rod Stewart had told me long ago regarding Jeff: ‘Don’t do it. You’ll do an album or two, and then it’ll be over.’ We didn’t listen to that advice, but that’s what happened. It ended up a mess at the end.”

Reports of arguments and physical altercations suggested that Beck was nearly impossible to work with, which was partly true. However, the main reason why the guitarist went through so many different lineups is that he was still searching to find his own musical voice.

It was particularly frustrating for Beck when his good friend Jimmy Page experienced greater success with Led Zeppelin using a similar heavy blues-rock formula Beck that pioneered on Truth, which preceded Led Zeppelin by about half a year. The fact that Zep also recorded a cover of Muddy Waters’ You Shook Me further salted his wounds.

Looking to move beyond the increasingly crowded blues-rock idiom, Beck became attracted to the allure of funk and R&B. This led to a botched attempt to record an album at Detroit’s legendary Motown studios in 1970 and the inspired, albeit ultimately underwhelming, hiring of Steve Cropper to produce the Jeff Beck Group album in 1972.

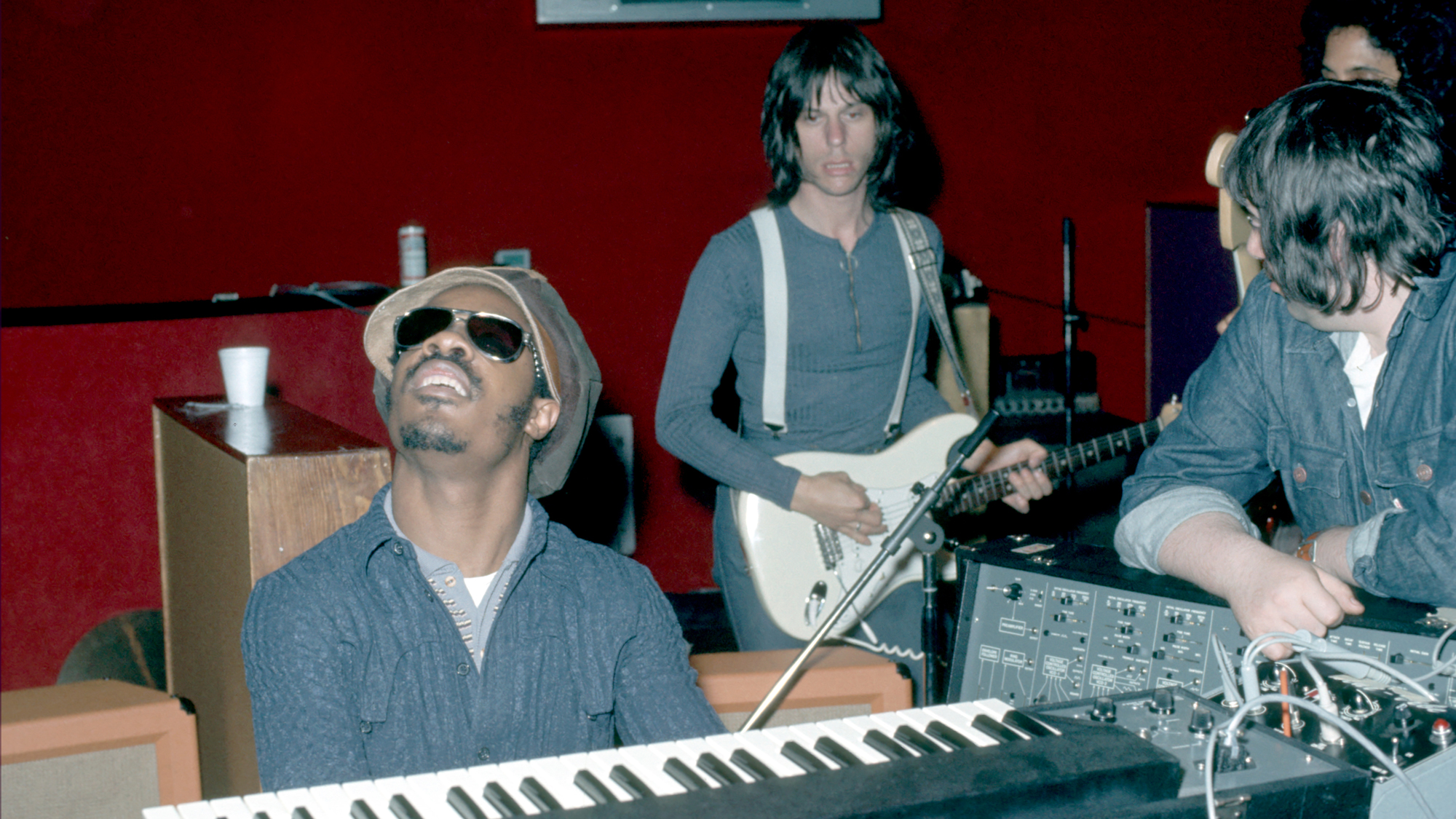

That album featured a cover version of Stevie Wonder’s I Got to Have a Song, which captured Wonder’s attention. Later that year, Wonder invited Beck to participate in sessions at Electric Lady studios in New York City for the album Talking Book. Beck played guitar on Lookin’ for Another Pure Love.

During the sessions, Beck also inspired Wonder to write Superstition when the guitarist was fooling around on the drums and came up with a driving, funky beat. Jamming on a Hohner Clavinet keyboard, Wonder wrote what Beck called “the riff of the century.”

Wonder planned on giving the song exclusively to Beck as a gift, but Wonder’s management quickly saw its potential as a hit single and demanded that he record it himself.

Beck later recorded a heavy rock version of Superstition for the first Beck, Bogert & Appice album, but its impact was ultimately thwarted by the dynamic brilliance of Wonder’s single.

Apparently feeling somewhat guilty for the events that transpired with Superstition, Wonder later eventually delivered another gift to Beck that proved to be even more beneficial to the guitarist’s career.

Enter fusion

Sometime during the early ’70s, a mishap led to a profound life-changing event for Beck. While working in his garage trying to repair a car he had crashed, Beck had an epiphany.

“I was looking up at the wreck of the car that I’d crashed, thinking I was finished,” Beck wrote in his book Beck01: Hot Rods and Rock & Roll. “I was working underneath the car and could hardly move. My head was on the ground and water was coming down the driveway. A little transistor radio was playing Miles Davis’s Jack Johnson [the track was Right Off, which is the entirety of side one].

“Lying there in the water, I realized I wasn’t done yet, and this music was going to save me. I went inside and just sat there, sopping wet, listening to the album. I thought I’d been resurrected, like a phoenix. I went out and bought the record and then found out about [guitarist] John McLaughlin and [drummer] Billy Cobham.”

Beck kept his newfound passion for this burgeoning style of jazz known as fusion, which added new exploratory elements of rock and electric instruments to the jazz vernacular, mostly to himself over the next few years.

He was fascinated with the improvisational and rhythmic possibilities that jazz-fusion presented for expanding the rock repertoire, especially since he was beginning to grow tired of playing the same blues-rock riffs.

“A handful of tapes knock me out,” Beck told Steve Rosen in the November 1975 issue of Guitar Player, “things like Billy Cobham, Stanley Clarke – all the great rock and rollers. I call Billy Cobham a rock and roller because he’s so forceful. Rock’s an energy to me. It’s more complex now than it was, but it’s rock just the same.”

Carmine Appice later claimed that he introduced Beck to Billy Cobham’s 1973 Spectrum album during their time together in Beck, Bogert & Appice, but by that time Beck seemed to already be familiar with Cobham and McLaughlin’s work together in McLaughlin’s post-Miles Davis band, the Mahavishnu Orchestra.

There was something like 30,000 people watching this ridiculously high-powered music: jazz-rock fusion, furious playing and outrageous time signatures. I thought, ‘This is more like it,’ and that’s where Blow by Blow came from

In fact, Beck allegedly cancelled shows by Beck, Bogert & Appice so he could attend the Mahavishnu Orchestra’s concerts in New York’s Central Park in August 1973. Even if Appice and Beck did share a common love of fusion music, that never emerged as a direction pursued by their band.

“I remember Mahavishnu Orchestra playing in Central Park at the Schaefer Music Festival in August 1973,” Beck wrote in Beck01.

“Between Nothingness & Eternity was the live album that resulted from that concert. There was something like 30,000 people watching this ridiculously high-powered music: jazz-rock fusion, furious playing and outrageous time signatures. I thought, ‘This is more like it,’ and that’s where Blow by Blow came from.”

McLaughlin’s guitar playing with the Mahavishnu Orchestra was raw, exhilarating and blazingly fast, as were Tommy Bolin’s guitar performances with Cobham on Spectrum. Both impressed Beck significantly, but the guitarist actually took more inspiration from the synthesizer player that both groups (as well as Stanley Clarke) shared in common: Jan Hammer.

“Jan gave me a new, exciting look into the future,” Beck told Guitar Player in 1975. “He plays the Moog a lot like a guitar, and his sounds went straight into me. So I started playing like him. I didn’t sound like him, but his phrases influenced me immensely.”

Possibly the ultimate turning point for Beck was when Mahavishnu Orchestra released Apocalypse in April 1974, which happened to be about the same time Beck disbanded Beck, Bogert & Appice and was seriously considering releasing a jazz-fusion album as a solo artist as his next career move.

McLaughlin had assembled a new lineup for his group, replacing Cobham and Hammer with drummer Narada Michael Walden and keyboardist Gayle Moran, respectively, but Beck barely noticed the absence of some of his favorite players. Instead, he was particularly blown away by the dynamic blend of aggressive guitar accompanied by lush orchestral arrangements performed by the London Symphony Orchestra.

Apocalypse was expertly produced by Sir George Martin, who called it “one of the best records I have ever made” in his 1979 book All You Need Is Ears. The album’s immaculate sound quality and energy convinced Beck that he needed to hire Martin to produce his solo album.

“I turned up at George Martin’s office with a diabolically bad demo,” Beck recalled, “but he could see there was something there.” Martin agreed to sign on to the project, and in October 1974 work on Blow by Blow commenced at London’s AIR studios.

The lineup

Beck reunited with keyboardist Max Middleton to write material and record Blow by Blow. Initially Carmine Appice played drums on the early sessions, but he was fired after he insisted on having his name appear prominently alongside Beck’s on the album cover.

“Carmine kicked up such a fuss about him wanting it to be his album,” Middleton told journalist Bruce Stringer in 2003, “so Jeff kicked him off and asked me if I knew anybody else. I brought in [drummer] Richard Bailey and [bassist] Phillip Chen because I knew them for some time, and that was how we did that album.”

Although Blow by Blow is commonly described as a jazz-rock fusion album, it’s really more of a jazz-funk fusion effort.

I was influenced by Larry Graham’s Graham Central Station… I played George [Martin] a couple of tracks, and he said it was the worst-recorded sound he’d ever heard

“I was constantly trying to put funk into the record,” Beck said. “I was influenced by Larry Graham’s Graham Central Station, which I was listening to on a loop in my car at the time. I played George [Martin] a couple of tracks, and he said it was the worst-recorded sound he’d ever heard.

“George wanted Beatles-esque orchestrations and strong melodies. I didn’t really appreciate what George was doing to the extent he deserved. I should’ve known better than to underestimate him. I didn’t take much notice of what he was gently trying to push me to do.”

Beck won the argument, of course, since it was his solo album and his name appeared on the cover. The funk element is strong and present from the get-go, with scratchy funk chords that are more than obviously inspired by Jimmy Nolen’s playing on James Brown’s Sex Machine kicking off the album’s first track, You Know What I Mean, penned by Beck and Middleton.

However, Beck’s adventurous solos and complex lead melodies showed listeners used to his heavy rock bluster that he was venturing deep into new territory.

“That Blow by Blow opening is pure funk,” says John McLaughlin, who co-headlined Beck’s 1975 tour in support of Blow by Blow.

“I’m sure that’s why he hired [drummer] Bernard Purdie and [bassist] Wilbur Bascomb, who both came from James Brown’s band, as his rhythm section for the tour. When we both got together to jam at the end of each show, we would be dancing on stage with that rhythm section just kicking our butts.”

Allegedly George Martin was not the biggest fan of Middleton’s reggae-inspired arrangement of the Beatles’ She’s a Woman. Beck had actually publicly leaked this arrangement of the Lennon and McCartney tune earlier when he performed alongside the band Upp, who he was producing, on the BBC’s Five Faces of the Guitar special broadcast in September 1974.

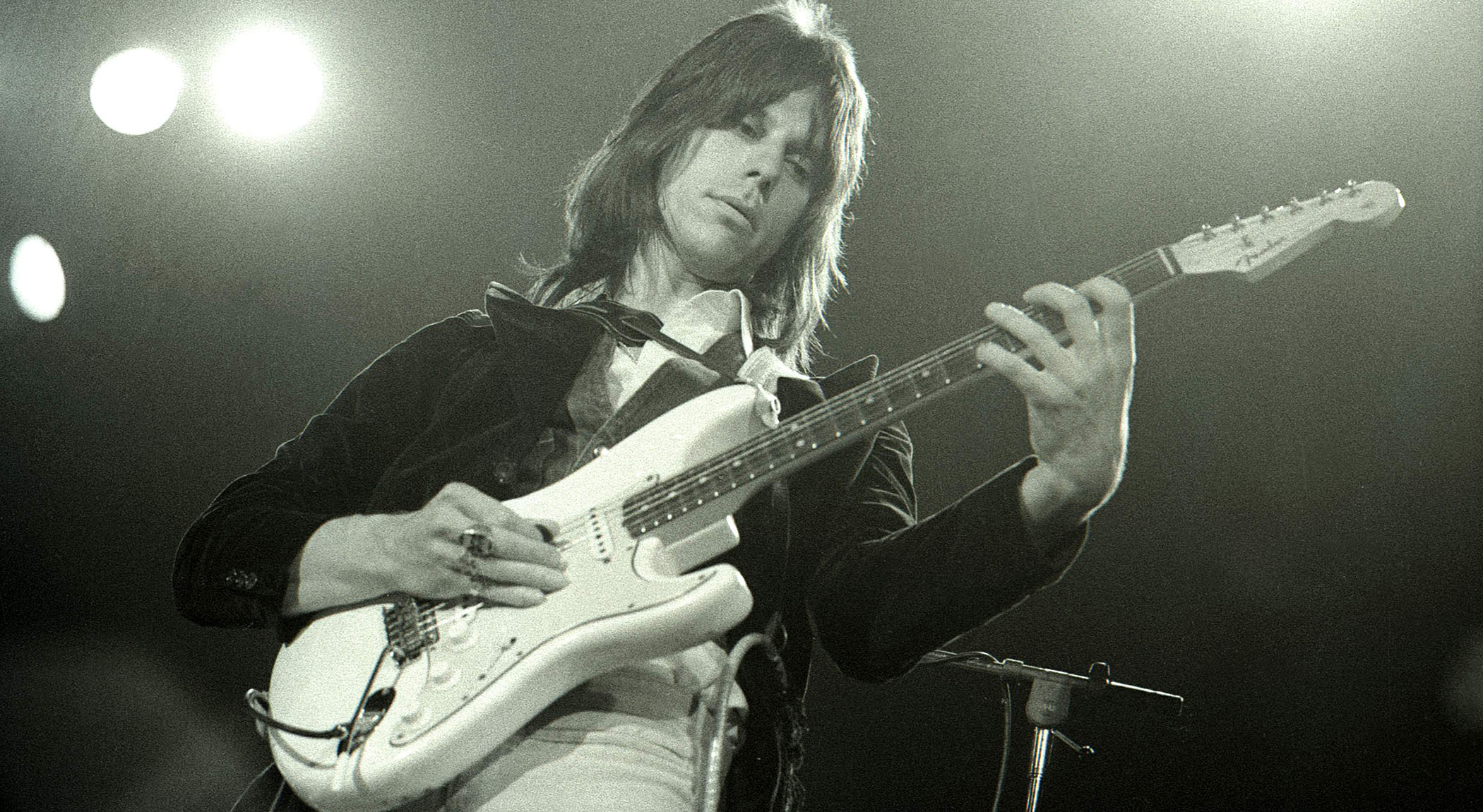

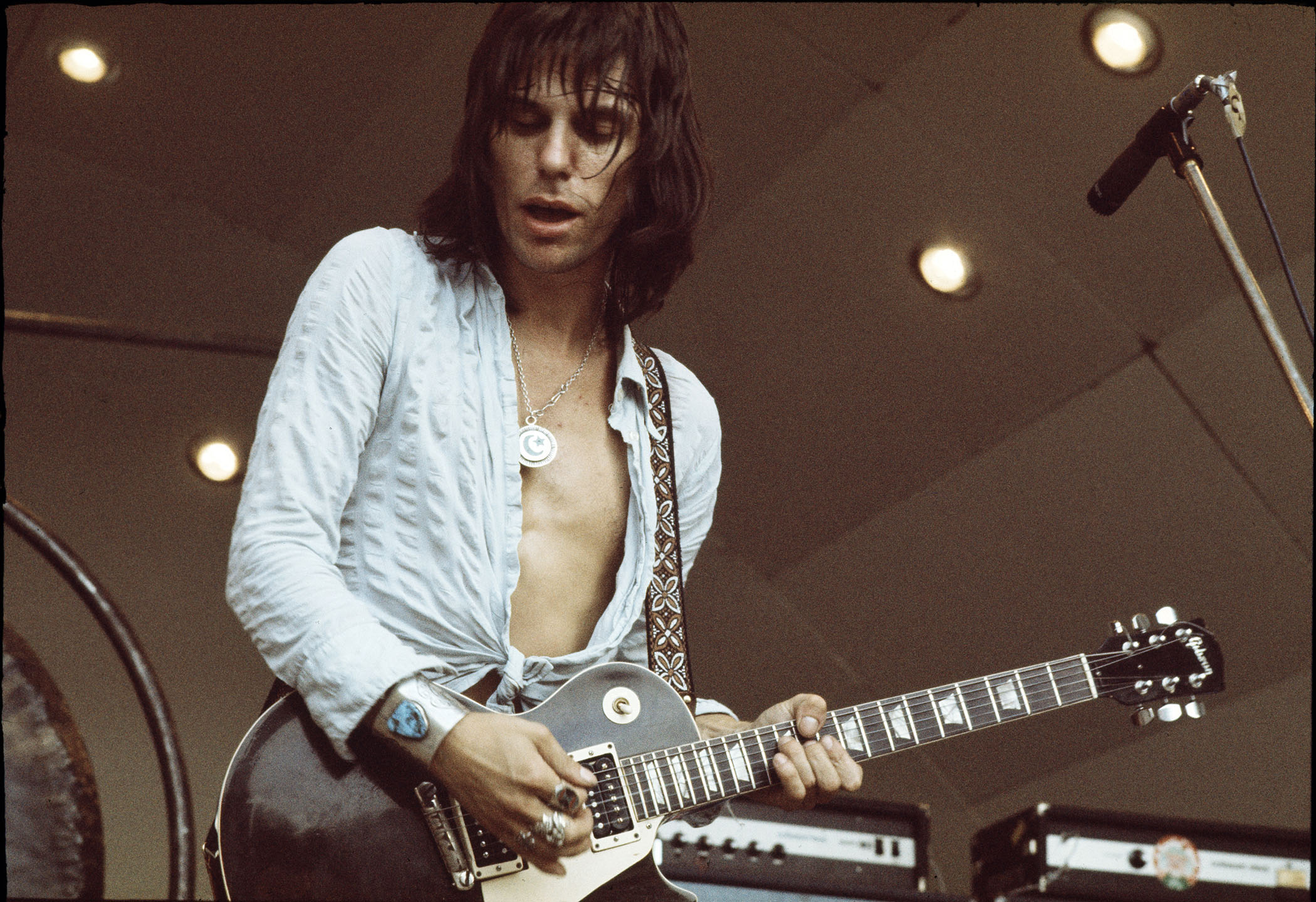

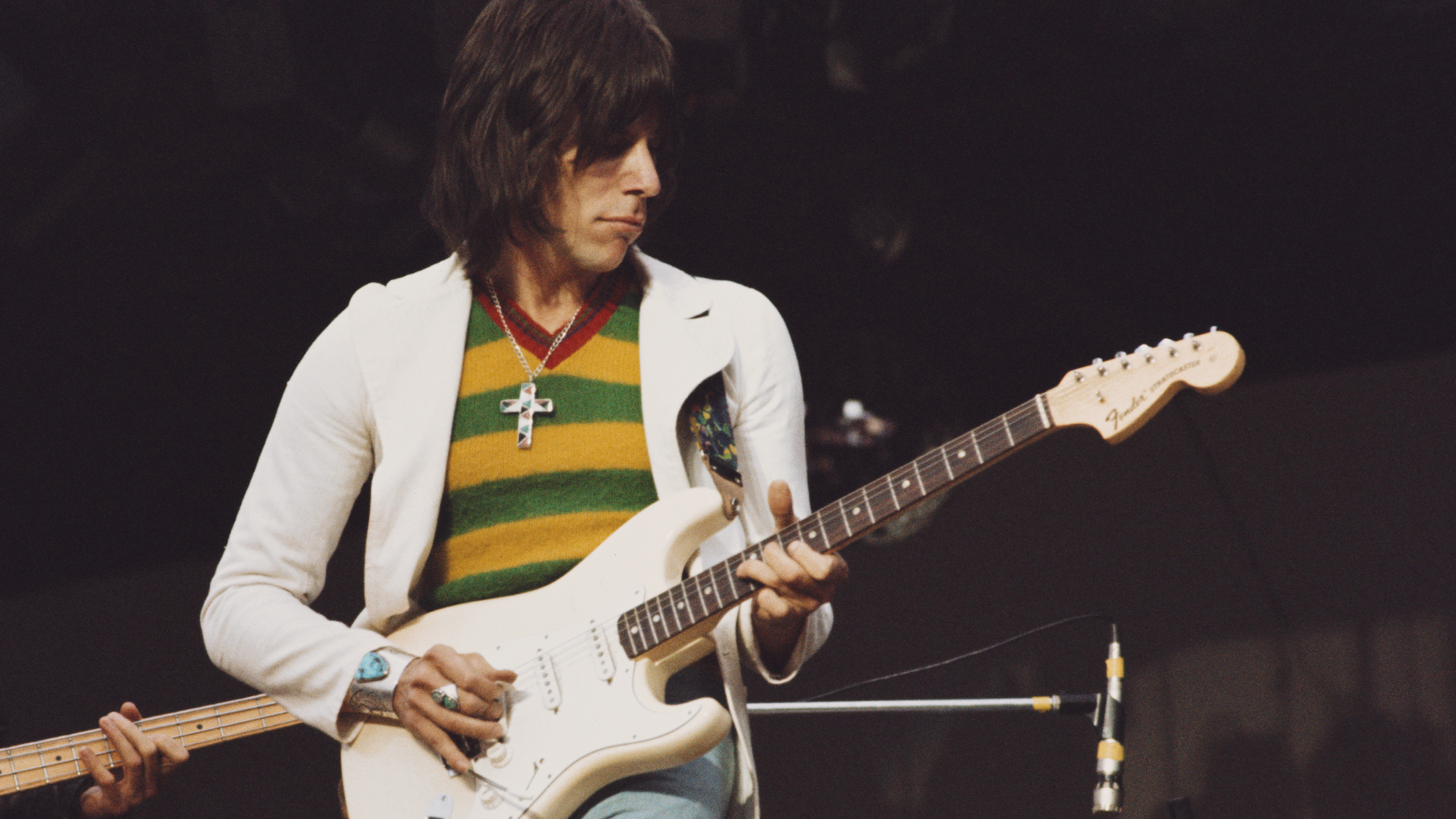

The BBC broadcast possibly provides a glimpse at the main rig Beck used while recording Blow by Blow. Here the guitarist was seen playing his modified 1954 “Oxblood” Gibson Les Paul, an Ampeg VT-40 combo amp, Colorsound Overdriver, Cry Baby wah, ZB Custom volume pedal and Kustom “The Bag” talk box, the latter heard prominently on She’s a Woman.

Other gear that Beck is known to have used on the album includes two Stratocasters – an early ’70s Olympic White model and one with a stripped-finish early ’60s body and mid-’70s rosewood neck – and the famous “Tele-Gib” 1959 Telecaster with two PAF humbuckers assembled by Seymour Duncan.

The Beck composition Constipated Duck pulls the album back into funk territory with Middleton’s clavinet licks and Beck’s trippy double-stop echo tricks. The guitarist’s distinctive note bends offer the first glimpse at Jan Hammer’s influence. More Nolen-style chords kick off AIR Blower (credited to the entire band) before the song quickly settles into a funk-fusion groove.

Beck’s gritty fuzz tone solos and harmonized lines in tandem with Middleton’s synth take the guitarist about as far away from his blues-rock past as Mississippi is from Manhattan, further punctuated by Beck’s jazzy lines around the 3-1/2 minute mark where a slow, loose tempo shift occurs.

Side one closes with Scatterbrain co-written by Beck and Middleton, which sounds the closest to the reason why Beck hired Martin to produce the album in the first place.

Here, the orchestral string section that Martin wanted all along finally makes an appearance, although it’s more subdued than the arrangements Martin employed on Apocalypse. The jazz fusion element is present and accounted for in full force, with some passages even bearing a slight resemblance to Mahavishnu’s Vision Is a Naked Sword.

Wonder himself makes an uncredited appearance playing clavinet on Thelonious, which he also wrote during the Talking Book sessions.

This is arguably the deepest funk track on the album, with grooves and riffs that almost match Superstition. Beck uses a Mu-Tron Octave Divider to summon a downright nas-tay horn- or synth-like tone, punctuated by talk box accents.

Next, Freeway Jam finally delivers the track that most closely fits the jazz-rock fusion description. This was also the album’s closest thing to a hit, receiving heavy rotation on FM album rock stations throughout most of the remainder of the ’70s.

Here, Beck is definitely playing one of his Strats, liberally using the vibrato bar to accentuate notes with wild warbling bends and deep dives. Like Lovers it also became a fixture of Beck’s live set lists.

Diamond Dust ends Blow by Blow with the accompaniment of a second orchestral string arrangement by Martin.

The song was written by Bernie Holland, who was the guitarist in the band Hummingbird, formed in 1974 by Middleton and other members of the second iteration of the Jeff Beck Group. The song is as much of a showcase for Middleton’s electric piano and synth playing as it is for Beck’s melodic motifs and soloing.

Aftermath

Beck acknowledged John McLaughlin’s profound influence by inviting the Mahavishnu Orchestra on a co-headlining tour in 1975.

“We just wanted to see if it was going to work, and boy, did it work,” recalled Beck. “The next thing I knew I was on stage doing a double headliner with John. It was a bit barbaric and chaotic, but it was more music per square inch than l’d ever heard. When we opened the show, the audience went utterly berserk.”

It was a bit barbaric and chaotic, but it was more music per square inch than l’d ever heard. When we opened the show, the audience went utterly berserk

Beck and McLaughlin’s cross-pollination of rock and jazz styles had made both outcasts of sorts from their respective main genres, but by banding together they helped lift each other up and beyond those restraints and biases.

McLaughlin was particularly touched by Beck’s acknowledgement of the Mahavishnu guitarist’s influence on his playing style.

“When you have an impact on somebody who is already a very fine musician, it’s kind of a little humbling, isn’t it?” McLaughlin says.

“Beck was kind of an outsider, and I got a lot of flak from the traditional jazz community where I was being told, ‘This ain’t jazz.’ But Jeff broke down those barriers, and now they’ve disappeared.

“Today it doesn’t matter what kind of music you play; it’s how you play it. When the spirit gets you, it doesn’t matter where you’re coming from – the spirit will be heard. Every musician that I know who heard Jeff loved him, and his spirit will live on forever.”

- This was a preview of the upcoming Jeff Beck biography Blow by Blow by Brad Tolinski & Chris Gill, scheduled for release in October by Grand Central/Hachette Books.

Chris is the co-author of Eruption - Conversations with Eddie Van Halen. He is a 40-year music industry veteran who started at Boardwalk Entertainment (Joan Jett, Night Ranger) and Roland US before becoming a guitar journalist in 1991. He has interviewed more than 600 artists, written more than 1,400 product reviews and contributed to Jeff Beck’s Beck 01: Hot Rods and Rock & Roll and Eric Clapton’s Six String Stories.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Ozzy Osbourne’s solo band has long been a proving ground for metal’s most outstanding players. From Randy Rhoads to Zakk Wylde, via Brad Gillis and Gus G, here are all the players – and nearly players – in the Osbourne saga

“I could be blazing on Instagram, and there'll still be comments like, ‘You'll never be Richie’”: The recent Bon Jovi documentary helped guitarist Phil X win over even more of the band's fans – but he still deals with some naysayers