“James Brown kept saying, ‘We’re gonna take it to the bridge.’ Finally, he whipped around and said, ‘Hit me!’ Unfortunately, I did not hit him at all”: Carlos Alomar was fined by the Godfather of Soul, scolded by Chuck Berry – and adored by David Bowie

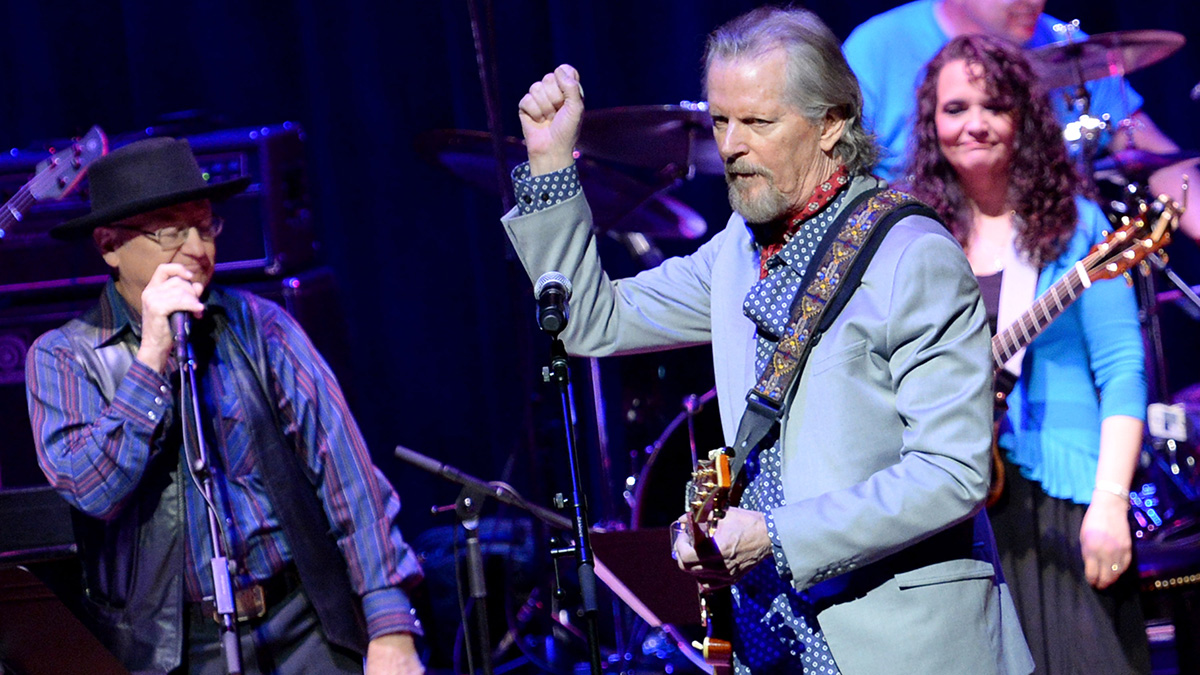

Playing professionally since his teens, Carlos Alomar was part of the DAM Trio rhythm section that backed David Bowie from the mid-’70s – and now, he says, it’s time to commemorate that legendary collective

Growing up in the Bronx, the shadow of the church loomed large over a young Carlos Alomar. But larger still was the shadow of a Sears and Roebuck guitar/amp combo gifted to him by his father as a teen.

Some years before when he was 10 years old and playing in his local church’s band, Alomar couldn’t have known that around a decade later, he’d be standing beside David Bowie as a member of the legendary DAM Trio – which featured Alomar on guitar, George Murray on bass and Dennis Davis on drums – and aiding in the creation of iconic records like Station To Station (1976), Low and “Heroes” (1977), and Lodger (1979).

Looking back on Bowie’s decision to put together a proper rocking band out of New York City, Alomar tells us:

“David left The Spiders From Mars and then he came to America. The fact is that he had this black rhythm section backing him all these years and nobody ever really said anything about it. As we get older, we have a legacy.”

Before then, Alomar starred with everyone from Chuck Berry to James Brown to The Main Ingredient. And once with Bowie, he held his own on tour while perched beside the likes of Earl Slick and Adrian Belew en route to becoming Bowie’s musical director and lifelong friend. Alomar stuck with Bowie – albeit in an on-and-off fashion – until the early 2000s.

Along the way, he appeared on records by Mick Jagger, Paul McCartney and The Pretenders, and even lent his licks to Mark Ronson’s 2014 mega-hit, Uptown Funk.

As for Bowie, the two kept in touch and Carlos took the iconic vocalist’s 2016 death from liver cancer hard. When many of Bowie’s past cohorts celebrated his career, Alomar, stricken with grief, chose to refrain (“Man, I would have started crying right in the middle of those songs,” he says).

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But now, Alomar is preparing to step out of the shadows. “I’ve got to be able to preserve that legacy. Brian Eno and David Bowie were very smart about taking that opportunity to introduce electronic music to the world via the [Berlin] Trilogy albums [Low, Heroes and Lodger].

“But it came at the cost of diminishing the great works that the DAM Trio had done. All the experimental albums got a lot of acclaim because of the electronica, but that was when we were at our strongest.”

I really want to do a tour to commemorate the life and times of David Bowie and Dennis Davis

Alomar is so passionate about the legacy of the DAM Trio that he’s called George Murray out of retirement and plans to insert any number of superstar guitarists into the mix.

“I really want to do a tour to commemorate the life and times of David Bowie and Dennis Davis,” Alomar says. “So I’m [doing] something that will honour the legacy of all those people I’ve admired and the music that has been my vehicle of expression,” he says. “It’s time for me to unleash that onto the world.

“It’s not my final dance,” he adds, “but it is a dance of purpose that I need to do, and as long as you’re curious, you’ll stay young. Right now is a wonderful time, like all times are. Everything’s in its time, and in its time, everything.”

How did your foray into guitar begin?

“It started after my father, a Pentecostal minister, gave me a guitar. The next thing I knew, that guitar came with obligations – not responsibilities, obligations. Suddenly, I found myself the only guitar player in church and I was about 10 or 11 years old. I knew three chords, man.

“But my father knew something that I didn’t and one day he went into my room and saw that there was blood on the sheets, so he pulled them back a little and realised that my fingers were bleeding. I had this old Stella guitar and the action was high… I don’t know what the hell I was thinking [laughs]. I think he knew I was dedicated to the instrument.”

Can you remember what it was about guitar that led you to persevere?

“There’s something mystical about an instrument to a small child. The metal key tuning pegs, the strings… It had wonder. And for a kid, man, that was everything. When I went to church and played, I played it like I meant it; I played it like I wrote the song.

By the time I was 14 I had formed a little band and we were rocking at church. I had the audacity to tell the minister, ‘If it wasn’t for my music, nobody would even come to this church’

“My father rewarded that dedication by taking me to the music store – and I was in awe. There was this Mel Bay chord book that said, ‘Learn 1,200 chords’. Dude, I knew three chords, so I bought that book. And it had pictures of fingers on the fingerboard. I studied that book like it was the Bible.

“I learned how to play a diminished chord and I practised every chord in that book, and everything was fine until I got to the dominant 7th chord. For all of you who don’t know what that means in the regular world, the dominant 7th chord is the rock ’n’ roll chord. When you hit that 7th chord, boy, your butt starts shaking [laughs]. That’s when I started getting into trouble. I was told, ‘You’re playing the Devil’s music,’ and I got put on discipline!

“By the time I was 14 I had formed a little band and we were rocking that church. Next thing I knew, I had the audacity to tell the minister, ‘If it wasn’t for my music, nobody would even come to this church.’ I got put on discipline [laughs].

“Anyway, my father says to me, ‘Carlos, what’s going on?’ And I said, ‘I’m playing God’s chords.’ My father died a little bit later, but he had bought me a Sears and Roebuck guitar amplifier, like a little grey amplifier with one speaker. That was it. That was my heaven.”

And it was around this time that you met Luther Vandross, right?

“After my father’s passing, I got to go to Fordham University for a program for underprivileged kids. The best part was during the summer when they took us to see plays. That’s when I met Luther, who became my best friend when I was 14 or 15.

I could hear them chuckling and laughing at my Sears and Roebuck guitar. But I plugged it in, played a solo and they applauded. I got the gig and that was the beginning of my life

“Luther had this opportunity to go to the Apollo Theater [in New York City] because there were auditions for this group. He said, ‘Carlos, come with me; I need moral support.’ So Luther sang and he got in that group, and the next week, he said, ‘Carlos, come back. I’m in.’

“So I sat down and watched, and the director said, ‘Boy, what do you do?’ I said, ‘I play guitar, sir.’ He said, ‘I don’t want to see your face around here unless you bring your guitar and show me what you can do.’ I said, ‘Yes, sir.’ But oh my God, I was from the Bronx, man. What the hell was a 15 or 16-year-old kid doing on the train with a Sears and Roebuck guitar, carrying my guitar and amplifier to the Apollo Theater?

“I could hear them chuckling and laughing at my Sears and Roebuck guitar. But I plugged it in, played a solo and they applauded. I got the gig and that was the beginning of my life.

“That group was the one that did the pilot for Sesame Street back in the day. People like Nancy Wilson, Cannonball Adderley and Flip Wilson would all come to see us. And not long after that, when I was 17, I started working around joints in Harlem.”

While working at the Apollo, you played behind Chuck Berry. How did that go down?

“He came in with this guitar, a beautiful ES-335, and he would lift the headstock up and down and that would tell you what to play. Depending on how he moved his headstock, you’d stop or start. That was it. And man, he walked in and said, ‘Okay, let’s go.’

“But I had the audacity to say, ‘Are we gonna rehearse, Mr Berry?’ He didn’t turn around; he whipped around and yelled, ‘We don’t rehearse rock ’n’ roll!’ Let me tell you, I still give my musical cues to this day with the headstock, just like Chuck Berry.”

You toured with James Brown a bit, too.

“With James Brown, I had an opportunity to do a small bit of roadwork with him on the East Coast. While I was playing with him, he kept saying, ‘We’re gonna take it to the bridge,’ but I had to wait for the cue. Finally, he whipped around and said, ‘Hit me,’ and, unfortunately, I did not hit him at all [laughs].

My father gave me a mantra: ‘If you can’t explain it, defend it.’ So I learned to talk real fast and to explain exactly what I wanted… And I was fired

“I missed the cue. So when I went down on Friday to pick up my money – in the old days, they used to stuff all your money in a small yellow envelope – I looked at the guy and said, ‘Hey, there’s $20 missing.’ He said, ‘Yeah, Mr Brown said you didn’t hit back.’ I was intelligent. My father gave me a mantra: ‘If you can’t explain it, defend it.’ So I learned to talk real fast and to explain exactly what I wanted… And I was fired.

“I was always taught patience and understanding, and I realised that I didn’t need all these credits with James Brown, I just needed one. And so, yes, I worked with Chuck Berry; yes, I worked with James Brown. But the anxiety of a job being where I’m supposed to stay forever was never a part of my mentality. When you don’t feel beholden to somebody else, it’s great.

“From there, I kept playing and getting more and more gigs. I’ve always had the mentality of, ‘You don’t owe me anything.’ Even with David Bowie, after I got to play with him on Young Americans, I was shocked that I got the second phone call and the third and the fourth and the fifth…”

Afterwards, you began your session career and recorded Everybody Plays The Fool in 1972 with The Main Ingredient.

“I got my first real job as the guitar player for The Main Ingredient. Everybody Plays The Fool became a hit and the next thing I knew, we’re going on the road. By then, I started getting really good and became the house player at RCA Studios.

“I was working in Studio A and during that time Tony Silvester [from The Main Ingredient] introduced me to David Bowie. I was really excited. That was the beginning of everything.

I said, ‘Gentleman, I’m so sorry, but honestly, I’m already making $800 a week; if you can’t match that, I ain’t doing it.’ I answered to a higher power – and that’s my wife

“Bowie said, ‘I’m working on an album. I’d like you to come down.’ The Main Ingredient had a hit and we were touring the East Coast. I was making money, I was married, so it was steady. So I got myself a white manager and I told my manager to negotiate something. And I heard, ‘Oh, maybe $200 and maybe we can get it up to $250.’

“I was making about $600 to $800 with The Main Ingredient and all the other jobs I was doing. So in the middle of that conversation, I said, ‘Gentleman, I’m so sorry, but honestly, I’m already making $800 a week; if you can’t match that, I ain’t doing it.’ I answered to a higher power – and that’s my wife [laughs].

“We stayed in contact and next thing I know, he’s recording again and he says, ‘I’m getting ready to do something and I want you to come down and work with me.’ He said he’d take care of the money. And he did. I was called up and told I’d be working on his new material, the Young Americans album. I showed up at the studio and that was it.”

What did your rig consist of at that point?

“During those years, I was more of a rhythm guitarist. My usual equipment was a Fender Twin Reverb amplifier, my go-to, and I had a red Gibson ES-335, which was so clean. I showed up with that 335 for the sessions and it was just glorious.”

What was it like touring with David for the first time?

“When I got the call to do the tour, they had this lead guitar player called Earl Slick and he rolled up with a Marshall stack with the volume turned to 11. It was just like the movies. The easiest thing for me to do was turn my amplifier down, but the minute I did, David turned around and said, ‘Earl, could you turn your amplifier down? I can’t hear Carlos.’”

Did your rig change much when you recorded Station To Station?

“That was when I got introduced to some new equipment and understood the value that equipment could have. While we were doing Station To Station, I said to David, ‘I can’t play with a Twin Reverb amplifier any more. Would it be okay if I got another type of amplification?’ He said, ‘Yes, whatever you want.’

“I ended up getting a customised system done and, to my credit, it was one of the first ever rack systems used on stage. I had a three-tier system and it was the size of a refrigerator [laughs]. Not only that, but I also had them do a crossover network so that I could cross over the amount of power that went into each unit.

“Luckily, during those years, we had a budget for everything. There were ridiculous amounts of money they were throwing at this man. The main rig then was my Alembic ‘Maverick’ Guitar, my MXR rack with a crossover and equaliser, and Crown power amplifiers. The speaker cabinets had tweeters, twin 12-inch fibreglass encased mini-cabs, and a 15-inch Gauss speaker bass cab.”

Rolling into the 80s, you worked with Mick Jagger, Paul McCartney, The Pretenders and more. What kept you in such demand?

“It comes down to two aspects: a musician should know their place and their style. I was always taught to say yes to everything. Anytime I got a phone call, I’d say, ‘Yes.’ Sometimes it’s like, ‘Do you play mandolin?’ I don’t own a mandolin, but I’d buy one. Did I know how to play mandolin? No. But have I played mandolin on records? Yes.

“But it’s not just the proficiency that you have on your instrument but the personality. Let’s say you have three choices for who is going to do the job; only one of them is the right one. You can have the quiet guy, who is always out front.

“And then the other guy who may have personality, he’s smart and plays really well – that’s the guy you want to go on the road with for eight months, that’s the guy that you can get along with. I was calm and played excellent guitar, a combination that helped me when trying to get a job.”

You’re planning to celebrate David’s music with other members of the DAM Trio. How do you think this will take shape?

“This is news for everybody, but, yes, I am planning to do a tour. I want to pay tribute to David Bowie and the DAM Trio. I want to do a tribute to the trilogy of albums we made in the 70s: Low, Heroes and Lodger. Why? Because that’s when the DAM Trio was at its height.

“I called George Murray, saying, ‘Hey, man, let’s put the band back together again.’ He said, ‘Okay.’ I think I want to use Vernon Reid from Living Colour or maybe Steve Stevens. I really want to highlight all the powerful stuff that we created during those times. Quite honestly, a lot of those pieces have never been performed in their entirety because they’re so damn difficult to play.

“I’m speaking to promoters now and getting the lay of the land. I’m really used to being a quiet sideman, man. I prefer to stay more hidden, but the time for staying hidden has to have a moment of clarity attached to it. And I think my vision is pretty clear about what I want to do right now.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

“The best guitar player I ever heard”: Nashville guitar extraordinaire Mac Gayden – who worked with Bob Dylan, Elvis, Linda Ronstadt and Simon & Garfunkel – dies at 83

“I’ve never bought a guitar and I’m quite proud of that! I always tell people when they’re learning: there’s a guitar not being played”: Meet Sacred Paws’ Ray Aggs, the dextrous Tele-wrangler inventing new chords and capturing Thurston Moore’s imagination

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)