“I was this short guy playing through a full stack, and the speakers were five feet from my head. It’s a miracle I can hear anything”: Buck Dharma on the Blue Öyster Cult story, his Gibson SG heroes, and what he really thinks of that SNL sketch

The names are invariably lifted from album and song titles. There’s Agents of Fortune, Spectres, Secret Treaties and, of course, Dominance and Submission.

They’re just some of the various Blue Öyster Cult tribute acts floating around, and the very mention of their existence elicits a curious chuckle from BÖC’s guitarist, singer and co-founder, Donald “Buck Dharma” Roeser. “I’m not aware of these things at all,” he says. “I’d be interested in seeing them. I find the whole thing rather surprising.”

Roeser has, however, kept tabs on artists covering Blue Öyster Cult material, and he gives high marks to the late Lisa Marie Presley’s take on Burnin’ for You (“She slowed it down, and it was really nice”), as well as two versions of the band’s signature song, (Don’t Fear) the Reaper.

“Big Country did a cover that I thought was terrific. And Tom Rhodes did a really dark and compelling version of it for a video game. He didn’t use the riff, but it still worked. I liked that one a lot.”

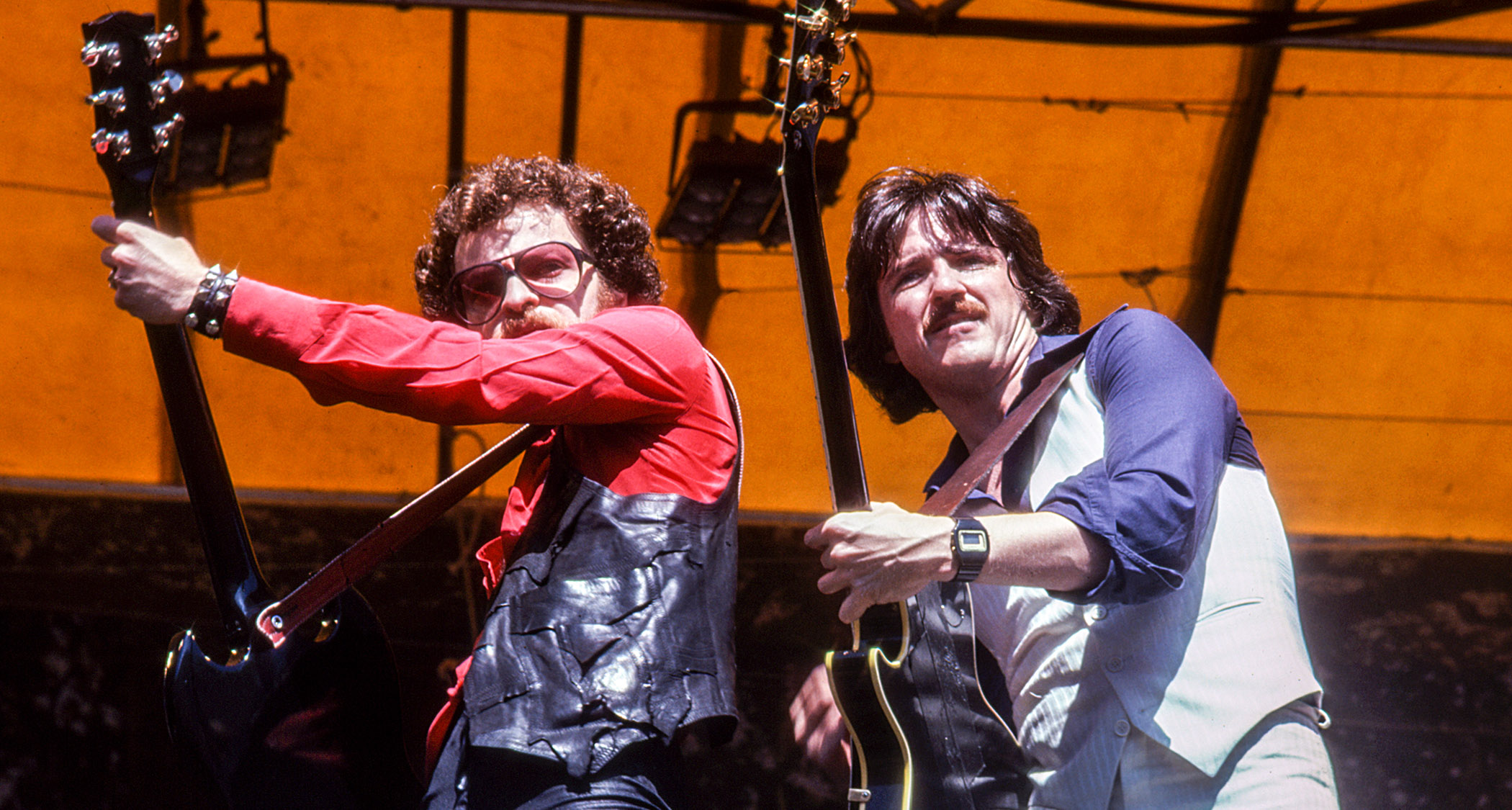

Blue Öyster Cult is now a six-decade old operation. At first known as Soft White Underbelly, the group’s five original members (Roeser, co-guitarist and singer Eric Bloom, keyboardist and guitarist Allen Lanier, bassist Joe Bouchard and his drummer brother, Albert) released a string of albums during the ’70s and ’80s that became classic-rock gems.

The band’s manager and producer, Sandy Pearlman, envisioned them as “America’s answer to Black Sabbath,” and while the group certainly dished up their fair share of doomsday riffs and horror film imagery, they also incorporated elements of pop, blues, jazz and even blasts of proto-punk into their songs (check out frenetic, piano-driven corker Baby Ice Dog, co-written by Lanier’s then girlfriend, Patti Smith, on 1973’s Tyranny and Mutation).

Recently, the band issued what could be their final studio album, Ghost Stories, a collection of archival material recorded between 1978 and 1983 (with the exception of a 2016 version of the Beatles’ If I Fell), and Roeser also has released nostalgic solo track, End of Every Song, which features Albert Bouchard on drums.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“My friend Bear McCreary did the orchestration. He’s a big Hollywood guy and has scored big TV shows and films,” Roeser says. “I got Bob Clearmountain to mix it, and he was brilliant. I never had the chance to work with him in the past, and I wish I did.”

Of the original band, Roeser and Bloom are the only two members who remain in the current BÖC incarnation (which also features multi-instrumentalist Richie Castellano, bassist Danny Miranda and drummer Jules Radino). The group continues to tour, though Roeser admits they don’t maintain the same backbreaking schedule as they once did.

“As long as we feel good and sound good, we’ll keep playing,” he says. “It’s a different group, but the current guys have been in the band longer than the original guys. And we still have the same vocalists, so that’s something. We’re taking some commitments for 2025, but there’s no promises for the future.”

He shrugs matter-of-factly. “We’re getting old, like all the other classic rockers.”

Going back to when you started playing, who were your main guitar influences?

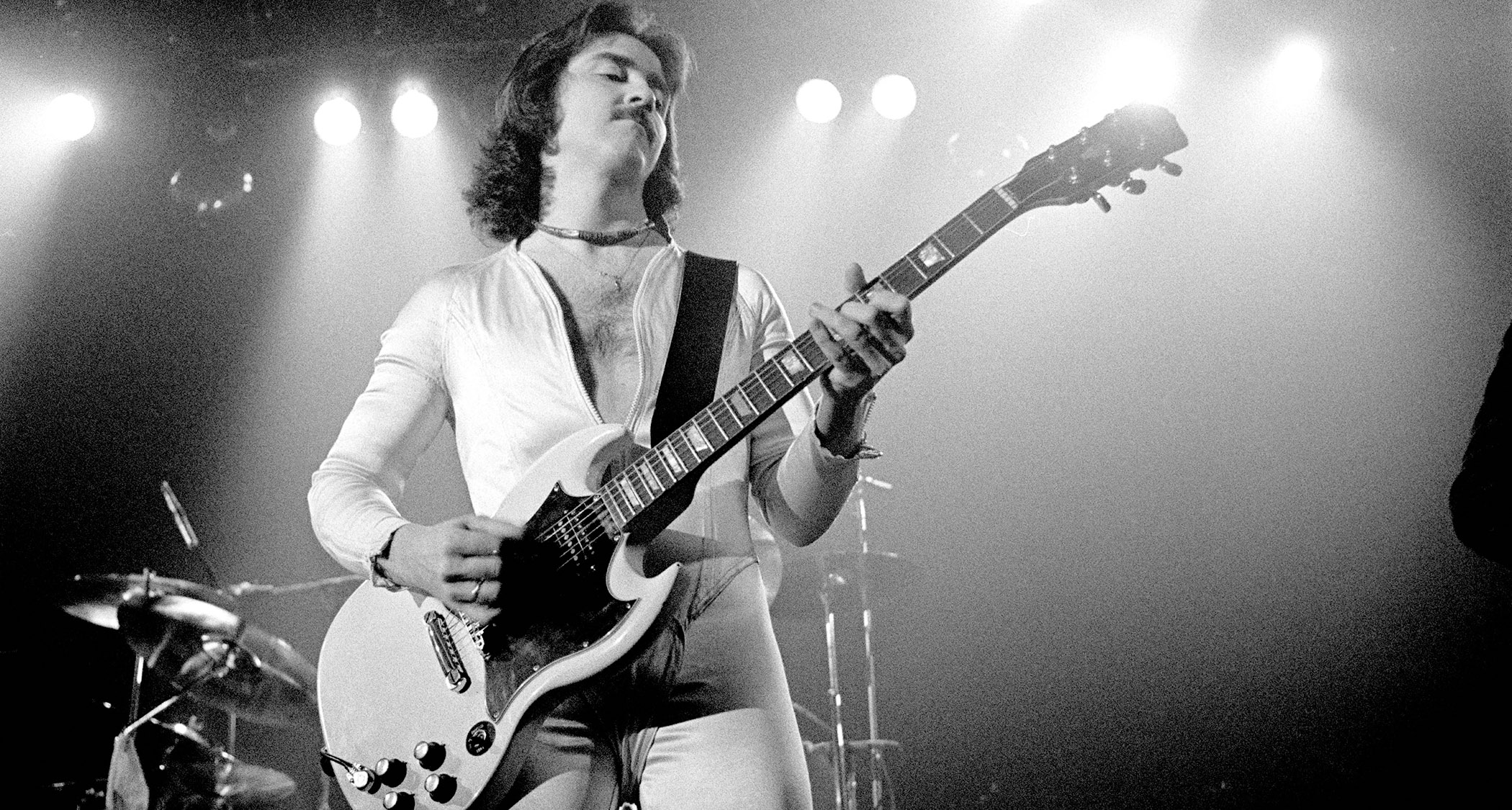

I was also into Robby Krieger and Carlos Santana. I played an SG in those days because of a lot of those guys

“I grew up with a crystal radio and caught the tail end of the doo-wop era and the beginning of rock ’n’ roll – Elvis and then into the Beatles and the whole British Invasion thing. Then came Hendrix and Cream and all the San Francisco psychedelic bands.

“I loved Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck. Ritchie Blackmore was a big one, and so was Jerry Garcia. I was also into Robby Krieger and Carlos Santana. I played an SG in those days because of a lot of those guys.

“Oh, but you know, another big influence was Danny Kalb from the Blues Project. In my college band, which Albert Bouchard was in, we played a lot of Blues Project covers. I had to woodshed to play Danny Kalb’s licks. He was kind of a fiery, showy, fast guitar player. I got my core technique from copying his stuff.”

Were you a natural on the guitar, or did you struggle with it?

“I was willing to put the time in. I started out on accordion when I was nine, but that felt pretty square. Then I took drum lessons and played in my high school band.

Sandy could have been an artist, but he really couldn’t sing, and he couldn’t play an instrument. But he was brilliant in terms of understanding what a song was

“Eventually, I went to guitar. My brother got a Stella acoustic for Christmas, and I played that – just started figuring things out. I got the Mel Bay chord book and learned what I needed – the seventh chords, the tonic chords, major and minor. I didn’t get too deep into the jazz chords.”

Very early on, when the band was still called Soft White Underbelly and played around Stony Brook University (in Suffolk County, New York), you hooked up with Sandy Pearlman. That really gave you a leg up on all the other bands in the area.

“That’s right. Sandy Pearlman was a rock critic for Crawdaddy magazine, and he was being courted by record companies. He approached the labels – ‘I got this band here. Can we make a demo?’ We went right into the recording studios.

“We were never really a club band before then. We got signed to Elektra early on and did some recording, but we never had a release because we fell out with the label due to Sandy’s personality.”

What was Sandy’s role as a manager? Did he help to shape your music, or was he more of an impresario?

“Sandy could have been an artist, but he really couldn’t sing, and he couldn’t play an instrument. But he was brilliant in terms of understanding what a song was. As a critic of music, he was really good. We all sort of learned as we went along.

“He recognized my talent as a player and really got me motivated to try music professionally. I probably wouldn’t have done it on my own if I hadn’t met him. I owe him my career in a big way.”

Were you on board with Sandy selling you as “America’s answer to Black Sabbath”?

“That was a promo angle, but it wasn’t a guiding principle of Blue Öyster Cult at all. Still, it was pretty cool to say. There was no American Black Sabbath, so it kind of framed what Sandy intended for the audience. In reality, we were a lot more eclectic and all over the place stylistically. But Sabbath was great. We were huge fans.”

The band was a slow builder and amassed its audience over the course of several albums. That kind of thing wouldn’t happen nowadays.

“No, not at all. Hats off to Columbia Records, because they signed us to a seven-record deal, and they were willing to roll the dice again and again. We worked hard on the road, and our album sales increased incrementally.

“We weren’t a pop act. We didn’t have a hit single until (Don’t Fear) the Reaper on our fourth record. But we didn’t mind the slow build. We were having fun and going to different places around the country and around the world. As long as we were always on the rise, it was fine.”

You must have played on some crazy bills. In the early and mid ’70s, there would be shows with three and four bands from completely different genres.

“Absolutely. We headlined a lot of shows with bands that went on to be headliners themselves. Those were great times. Bill Graham used to book shows like that where you had bands of multiple genres all playing the same night.”

What was that like for you guys to be on the same bill as, say, a folk act?

“It was great – the crowd would be into us. In fact, I would be embarrassed if our crowd gave another act a bunch of crap. We played with the Raspberries once, and our crowd wasn’t picking up on what they were doing. I thought the Raspberries were really good.”

You played a Gibson SG quite a bit back then. What kinds of amps did you pair it with?

“We got Marshalls when those amps started to happen after Jimi Hendrix and Cream. And, of course, the only way to get the tone out of a Marshall was to turn it up. It was kind of funny; I was this short guy playing through a full stack, and the speakers were about five feet from my head. It’s a miracle I can hear anything.”

How did the band’s three-guitar lineup evolve? And who came up with Eric Bloom being credited with “stun guitar”?

“That came about because the three of us – me, Eric and Allen – played guitar, so we arranged our tunes for three players. Eric liked to step on a fuzz pedal for a lot of his parts, so we ended up calling it ‘stun guitar.’ We didn’t really put a lot of thought into it in terms of intention. It’s just what we did.”

I imagine, however, you had to work out the parts so nobody was stepping on somebody else’s toes.

“Yeah, of course you had to do that. You sort of learned about arrangements and stuff and how to make a song sound as good as you wanted it. It was trial and error.”

Okay – Reaper. The riff is iconic. Is that how it all started?

I think everybody thought Reaper was a good song... I thought, especially when the band recorded it, that it would be a strong FM cut

“Absolutely. The riff came first. I wrote it using a TEAC 340S [reel-to-reel recorder], which was breakthrough technology for musicians at the time. Nowadays, you can overdub as much as you want on a laptop, but back then you couldn’t do it outside of a recording studio.

“I was noodling around, and the riff just occurred to me. I recorded it and immediately began working on the song that became Reaper.

“The first two lines of the lyrics sprang into my head, too. After that, it was about six weeks of getting the story together, working on the bridge and the conclusion of the arrangement. I made a demo, which is pretty much the way the band recorded it. They put some muscle and finesse into it, but it basically stayed the same.”

I talk to musicians all the time who say, “I never thought such and such song would be a hit.” Did you think you had something with Reaper?

“I think everybody thought it was a good song. Sandy Pearlman was pretty convinced it was going to go somewhere, and I thought, especially when the band recorded it, that it would be a strong FM cut. I didn’t know it was going to cross over to AM, which was pop radio.”

Once you had a hit song, did the label pressure you to come up with another?

“The pressure was applied equally, but a lot of it was internal. When you have a hit, you want another one, and everybody expects another one. We thought, ‘Okay, we’re here now, and we’re going to follow this up and do whatever.’

“Burnin’ for You was a hit, and Godzilla was something of a hit, but the kinds of songs that carry the day, we didn’t have ’em one after another.”

From what I gather, you weren’t bothered by the now-famous Saturday Night Live skit that lampooned BÖC cutting Reaper.

“No, not at all. Frankly, we never took ourselves too seriously as artists. I mean, we liked to be appreciated, but we did a lot of stuff for the humor of it. Take a band like the Tubes – they would’ve been a lot bigger if people appreciated their humor. And, of course, we all thought Spinal Tap was hilarious.

“When we did the Hear ’n Aid recording session with Ronnie James Dio, the Spinal Tap guys were there. I heard a couple of artists grumbling, and I thought, ‘Really?’”

Is there any one BÖC album that you feel epitomizes the band’s sound?

I’m a pop guy at heart. I wrote a lot of stuff that wouldn’t go on the band’s records

“Hard to say. I think fans and critics would probably pick our first three records, and probably our third [1974’s Secret Treaties] would be their favorite. But then you’ve got Agents of Fortune and Spectres, and there are the records Martin Birch produced – Cultösaurus Erectus and Fire of Unknown Origin.

“They all represent sections of our career. To pick one really depends on which song you like or what period you want to go with. I don’t really have a favorite.”

You’ve issued only one solo album – 1982’s Flat Out. Most of the material was songs the band deemed too “poppy.”

“That’s true. I’m a pop guy at heart. I wrote a lot of stuff that wouldn’t go on the band’s records. Burnin’ for You was supposed to be on my solo record – that was the plan – but Sandy Pearlman convinced me to have the band do it. And that made sense since it would have been bigger with the band playing it than if it wound up on a Buck Dharma record.”

Are you still playing that Steinberger “CheeseBerger” guitar?

“I am. I went to a NAMM Show in ’85 and came across Steinbergers for the first time. I’d seen other sort of jazzy players with them, but this was the first time I played one myself. I developed a relationship with the company and got a bunch of their guitars.

“The CheeseBerger was made after Gibson bought Steinberger, and they moved the factory from Newburgh, New York, to Nashville. I’ve had the CheeseBerger for 30 years now, and I still play it.”

What’s the secret to that guitar?

“I really like the neck. The guitar is very durable as far as touring goes. It doesn’t warp, nor does it take a lot of maintenance. It just works. I like the EMG pickups, even though they don’t have a strong personality. They’re sort of neutral, which allows you to shape what the guitar sounds like. I just like it.”

- Ghost Stories is out now via Frontiers.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“There’d been three-minute solos, which were just ridiculous – and knackering to play live!” Stoner-doom merchants Sergeant Thunderhoof may have toned down the self-indulgence, but their 10-minute epics still get medieval on your eardrums

“There’s a slight latency in there. You can’t be super-accurate”: Yngwie Malmsteen names the guitar picks that don’t work for shred

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)