“I had doubts about the Red Special – I knew it sounded different from what everybody else was using, from a Strat and a Gibson. But hearing it back was thrilling”: Brian May on reworking Queen’s regal debut, bad reviews, and Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Magic”

As the new Queen I boxset drags once lost songs into the daylight, May tells us about poverty, parental disapproval, the Red Special’s first runout – and the perils of playing through Jimi’s Marshall stack

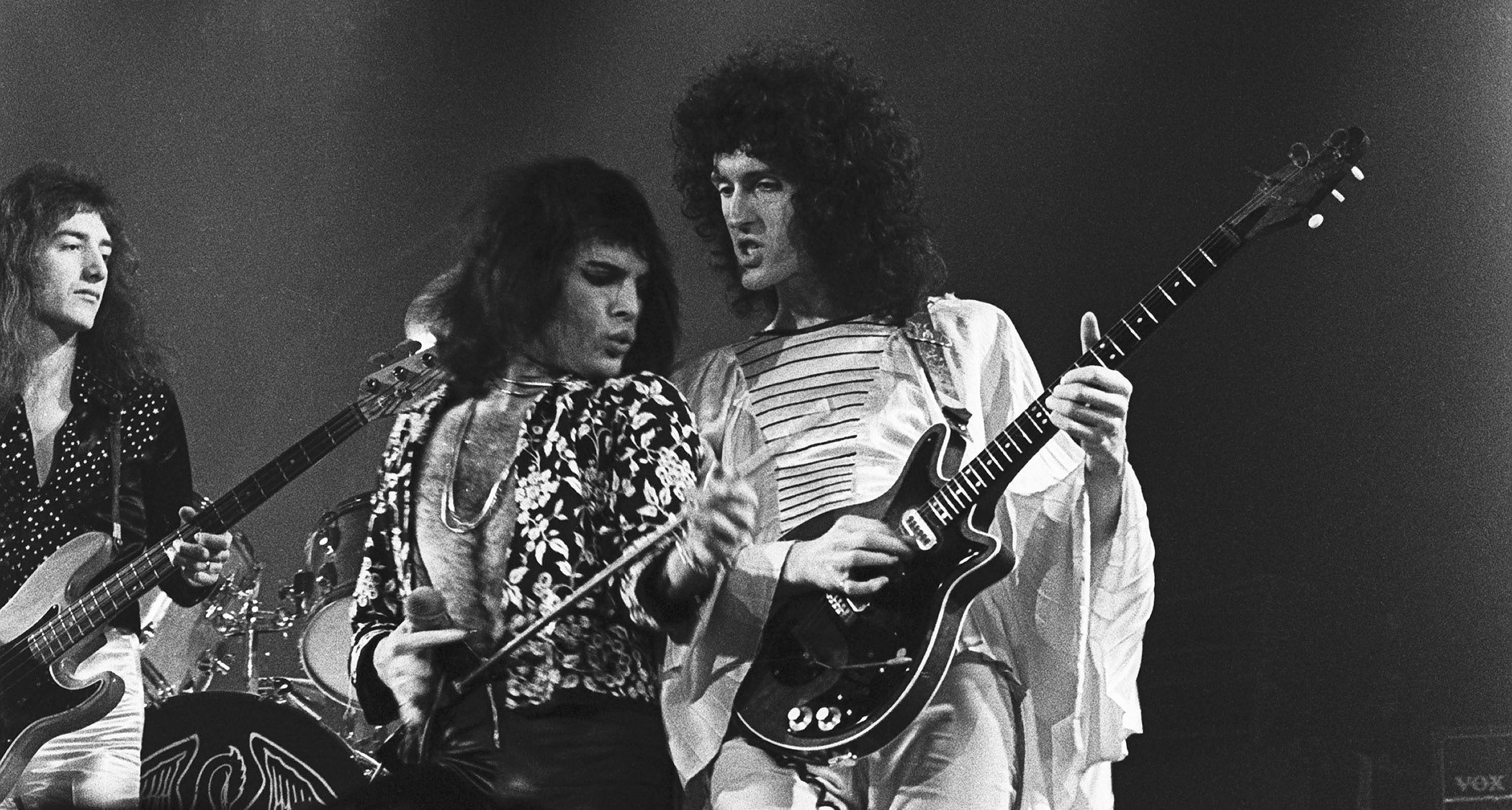

Half a century later, when discussing the road to Queen’s self-titled 1973 debut album with Brian May, it’s necessary to suspend your disbelief. Imagine, if you can, a time when the classic line-up of May, Freddie Mercury, John Deacon and Roger Taylor were not multi-platinum national treasures.

A time, in fact, when they were penniless nobodies, typically found bottom of the bill at a sweatbox club, being ushered from record label offices or facing tough questions from parents convinced these four bright boys were burning their futures for an impossible dream.

Appearing on our Zoom call in a halo of grey curls, May can smile about it now, knowing what lay ahead. In spring ’72, the band cut their first chink in the industry’s formerly impenetrable armour as they were granted nocturnal recording sessions at the famed Trident Studios.

And with precisely nothing to lose, the music flooded out, with the visceral gallop of Keep Yourself Alive leading them across the gamut of soul-metal (Doing Alright), proto-prog (My Fairy King), acoustic percussive tapping (The Night Comes Down), even flashes of flamenco (Great King Rat).

The first Queen record is a head-scratcher, though. Selling modestly on release, for 51 years, it has been the closest thing this all-conquering band had to a curio, its tracklisting unfamiliar to fans who know every note of, say, A Night At The Opera or The Works.

In that same period, the band, too, had an uneasy relationship with their opening gambit, frustrated by the album’s dry, distant sound. It’s a thorn plucked in style, however, by the new Queen I boxset: a paving slab-sized vinyl/CD package whose remastered and expanded treatment finally reveals these songs as sunken treasures to rank among the band’s very best.

If there is one final, jarring aspect of discussing May’s distant youth, it is the 77-year-old’s recent brush with mortality. In late August of 2024, the guitarist was set to conduct this interview when he suffered a minor stroke that left him temporarily unable to use his left arm.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

With customary kindness, May rescheduled when his health mercifully returned, and our first question had to be how this great friend of the magazine is bearing up.

Your stroke must have been frightening. Did you wonder whether you’d play guitar again – or was that the least of your worries at the time?

“It went through my mind. When I suddenly couldn’t control this left arm, it was quite scary. I had no idea what was going on. I phoned my doctor and she said, ‘Okay, I think you’re having a minor stroke. Dial 999, get in the ambulance and I’ll see you there.’

“But even at the worst time, although I couldn’t control where the arm was, I could control my fingers. So I thought, ‘I’m probably not really in danger.’ I’m all right now. I’m just taking it slow.”

The first Queen album is largely a story of struggle, isn’t it?

“It was very tough. And I sometimes wonder if that helped to shape us because everything was a fight. It was a fight to get into a studio. It was a fight to get our own way – and we didn’t, entirely, because we were just boys and everyone else was more powerful. It was a fight to get it released – and then it got completely slaughtered by the music press.

“But later I learned we weren’t the only people being hit by those destructive arrows. In fact, that’s one thing that cheered me up. I remember they gave Led Zeppelin a bad review, and I just thought, ‘Well, Jesus Christ, if they don’t understand that [throws up his hands]…’”

Likewise, every label rejected your demo recorded at De Lane Lea Studios?

“Nobody bit. Not one record company wanted it. Some of them said, ‘Come back in a few years, we’ll talk to you then.’ Again, it strengthens your resolve. You look inside yourself and you think, ‘No, actually, I do believe in this.’ Very early on, as soon as we had John, we really felt we had the power.”

Perhaps it’s no surprise your father didn’t approve of your musical career. But could he really complain, given that he helped you build the Red Special?

“Well, you wouldn’t think he could complain – but he did! He liked helping me with my hobby, but when the hobby became my career, he was very unhappy. I think he also felt he’d sacrificed a lot of his own life to enable me to take my education so far.

“Me giving that up was the worst thing he could imagine. So it was hard for him. It took a long time to sort that out. It only got sorted when I flew him to Madison Square Garden on Concorde, sat him down and said, ‘Okay dad, what do you think?’ A great moment. I think we all need that approval from our parents, don’t we?”

The early ’70s was the golden era of blues-rock. And Queen were definitely not that.

“There were a lot of people staring at their feet on stage. I don’t know if that made it easier or harder to break through. We just knew what we wanted to be. It was very arrogant of us, but we had big dreams.

“We wanted to give people the experience we’d felt watching The Who at Regent Street Polytechnic. They were an hour late, and when they finally got on stage, it was like an earthquake.

“We wanted to give people that same intake of breath. The sound, the lights, the performance, the clothing, the drama – give them everything we had. And, yes, it was very different from the mood of the day. It also wasn’t glam-rock. That was going on at the same time and it’s very much about the glitter or whatever. Which we weren’t.”

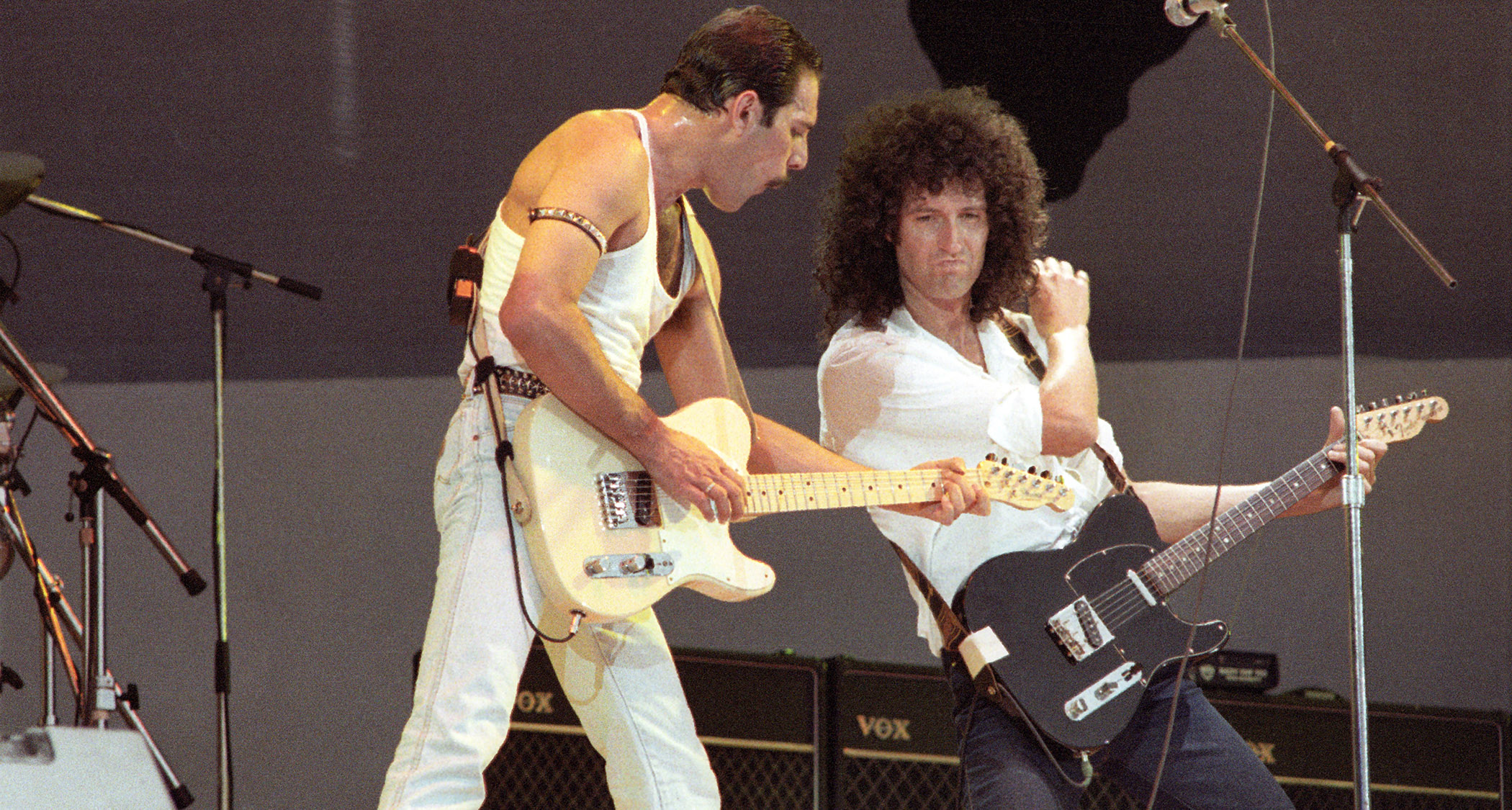

As a live band, could you have competed with Black Sabbath or Led Zeppelin?

“Well, we had to. There’s videos from the early days and I think we were pretty good. Very early on, we arrived at this view that being a live act was not the same as the studio. Actually, it was simpler because there’s only four of us on stage and no overdubs. It took me a long time to feel confident about being the only guitar on stage.

“I always felt like I needed a rhythm guitar. But, gradually, I got into this habit of playing lead and rhythm at the same time – and I realised that nobody noticed the lack of it. So we had enough. You could fashion that live performance to make people feel they’d heard an orchestra.”

It was while recording Queen’s demo that you first tracked a three-part solo. How did that feel?

I realised it would be possible to build up whole panoramas of orchestral sounds but with guitars. So I had this vision that the solo for Keep Yourself Alive could be this three-part sequence

“Amazing. That was in my head long before I could actually make it happen. It goes right back to hearing Jeff Beck on Hi Ho Silver Lining, where he double-tracks his lead. I never asked him about it, but he goes into a two-part harmony – probably accidentally – halfway through. And I realised it would be possible to build up whole panoramas of orchestral sounds but with guitars. So I had this vision that the solo for Keep Yourself Alive could be this three-part sequence. But to actually make it happen was a great moment.

“Okay, there was one predecessor, when I did a two-part harmony on Earth, a single we did as Smile. But the three-part harmony is the big deal. Because things suddenly get colourful if you use three parts in creative ways.

“Not just parallel 3rds and 5ths, which is an easy trap to fall into; I never wanted to do that. I always wanted the tensions and colours of dissonance and counterpoint. Everything that an orchestral arranger needs to know, you have to get in your head if you’re going to do something that endures.”

Eventually, the sessions proper began at Trident. How was the atmosphere?

I’m surprised, looking back, how complete I was. I don’t think I can play that much better now than I could then

“We were pretty jolly. This was an amazing opportunity, and we were all leaving our supposed careers behind. In a sense, we were aware we were leaving our families and friends behind as well. Because once you put a foot on that road, it takes you a long way from everything you know. But we had each other and our belief that we were doing something special that nobody else could do. We had that insane optimism.

“Through the years, there’s been times when there was tension from trying to paint on the same canvas. You’re feeling sidelined, your baby is being neglected or whatever. But in the case of the first album, that hasn’t happened yet. We’re just thrilled to be there.

“So on the ‘Sessions’ CD in this boxset, you hear snatches of us baiting each other, having a laugh. But you can also tell we’re serious about what we’re doing. We get frustrated when it’s not right, when we can’t get the blend or things aren’t in time. Making that album was an amazing exploratory process. It’s like giving a sculptor his first bit of clay and saying, ‘Here you go.’”

Could you immediately relax as a studio player or did that take time?

“There’s a definite learning process. I remember finding that with the backing tracks you could immerse yourself and let go fairly quickly. Overdubbing is actually harder to keep the spontaneity. Because you’re standing there with your headphones on. Your guitar is revved up. And you’re waiting for your moment.

“It feels unnatural. But I got into this little trick where I fooled myself into thinking I was playing live, and when the moment hit, I was on stage and there were people out there watching.”

How would you describe yourself as a guitarist back then?

“I’m surprised, looking back, how complete I was. I don’t think I can play that much better now than I could then. It had all happened in the teenage years. It’s quite a hothouse, where I came from. Richmond and Twickenham is where The Yardbirds and Rolling Stones came from.

“I had lots of mates to play with and there was fierce competition. You know, ‘Have you heard this latest solo? How did Hank Marvin do that? Can you do that?’ So I learned quickly, and maybe you do when you’ve got that amount of passion and hunger in your body.”

Would you play anything differently if you were tracking that debut album now?

“Actually, no. We’re rebuilding the sound on the boxset. But we didn’t feel the urge to change any of the performances. It would be different, but it wouldn’t necessarily be better. I honestly wouldn’t change a note – and we didn’t.”

That was the first run-out for your homemade Red Special. Wasn’t there pressure to use a standard production model?

“Not at the time. I remember, much later, when we did Crazy Little Thing Called Love, I said, ‘I want a James Burton atmosphere on the solo, so I’m going to make my guitar sound like a Telecaster.’ And the producer, Reinhold Mack, who’s a dour old sod, said, ‘Well, why don’t you just play one?’ But that’s probably the only time in my whole career when I’ve given way.

“The Red Special held up surprisingly well. I did have doubts in the early days because I knew it sounded different from what everybody else was using. It was different from a Strat: it’s warmer. It’s different from a Gibson: it’s got more top-end. It’s got a very wide sound.

“But hearing it back through the speakers was thrilling. Everyone had told us, ‘Nah, it’s never going to work.’ But hearing that stuff coming back, we thought, ‘We can conquer the world.’ We weren’t a modest lot [laughs]. But that self-belief has to be there. It has to be the source of your power.”

“You know, the Red Special was designed to make that kind of noise. We wanted it to sing. We wanted it to feed back. That’s why it’s got the acoustic pockets in the body. I still don’t know if it was all thanks to our design or luck, but it just made that sound. Still does.”

Were the other elements of your classic rig – the AC30 and Dallas Rangemaster treble booster – already in place?

“Yes. That was there from the moment I saw Rory Gallagher and managed to stay behind at The Marquee when everyone had gone home. I asked him, ‘Rory, how do you get that sound?’ And he said, ‘Well, it’s easy, I have the AC30 and this little box, and I turn it up and it sings for me.’

“The next day, I went to a guitar shop and found two secondhand AC30s for £30 each. I found a treble booster. And that did it. I plugged in with my guitar, turned all the way up and it just melted my stomach. That’s my sound. And it’s different from Rory’s. His is much more bright.”

You came up in the era of the Marshall amp stack. Did that never call to you?

Jimi came on stage, plugged into that same amp – and it sounded like cataclysm. I think he had some kind of voodoo magic, but he made that amp sound like an orchestra

“It did – but it was a false call! I remember, we played one show at Olympia. Top of the bill was Jimi Hendrix and everybody essentially played through the same gear. So I plugged into a Marshall stack with my guitar and treble booster. Turned it all the way up – and it sounded so awful. I could hardly play. I didn’t know what to do.

“It sounded like an angry wasp. It didn’t have any depth or articulation, I couldn’t play chords. It was a really hard experience for me.

“After we’d played, I stayed behind backstage and I looked through between the amps as Jimi came on stage, plugged into that same amp – and it sounded like cataclysm.

“I think he had some kind of voodoo magic, but he made that amp sound like an orchestra. And for me, it just didn’t work. So I never got on with Marshalls. I knew Jim Marshall and got on with him very well, but I could never quite tell him, ‘Sorry, I can’t quite get to grips with your amps…’”

How did Roy Thomas Baker record your guitars?

Roy was under pressure to get that ‘Trident sound’, which was very clean, guitars all tight – and it wasn’t what we wanted

“Roy was a brilliant technician, but his head was in a completely different place from us. He’d been recording things like Get It On, when he’d plugged Marc Bolan’s guitar directly into the desk. So it had no ambience whatsoever. You have no natural amp sound, no compression or smooth distortion. All you have is the direct sound of the guitar, and if you turn it up a lot, it distorts the electronics in the desk – which is a nasty sound, I would say.

“So this was the complete opposite of the way I wanted my guitar to be recorded. I wanted it to have the sound of the amp and the room. So we had a bit of a fight. To be fair, Roy and I had a long relationship where we evolved really good ways of recording guitars.

“But in those days, it was such a rush. And Roy was under pressure to get that ‘Trident sound’, which was very clean, guitars all tight – and it wasn’t what we wanted, but that’s what we got because of pressure from above. The Sheffield brothers [Norman and Barry] wanted it to sound like an album that had the signature sound of Trident Studios. And we wanted to sound like Queen.”

What are your own favourite guitar moments?

“I love My Fairy King. We were experimenting with backwards stuff and I used to get the guys to turn the tape over and give me a cassette I could take home, so I was ready when we came into the studio.

“Keep Yourself Alive was supposed to be ironic, a reaction to the idea that life was just about keeping yourself alive. But I discovered it’s hard to be ironic in a rock song. It came out sounding jolly. And in the end I didn’t fight it because people got a lift from it, so why not?

“That riff goes all the way back. I remember playing it on acoustic at parties, late at night, when people are sitting around. And I remember being surprised that people were impressed because I was a loner and didn’t very often play to people. I remember everyone surrounding me going, ‘Wow, we’ve never seen that before.’”

What’s happening at the start of The Night Comes Down?

“That was played on a very unorthodox guitar. It’s a little acoustic that had belonged to my best friend at school, Dave Dilloway, who drilled holes all over it to put pickups on. So it looked a mess. I put my own bridge on and made it lower and lower until eventually the strings were buzzing on the frets.

“But I thought, ‘Well, I actually like this, it sounds like a sitar.’ So I designed the bridge with all sorts of junk, like needles and pins, to make each string buzz. It’s a guitar that no-one else would take seriously, but it made that particular noise on The Night Comes Down. I’m tapping it and making it buzz, and John is playing in unison with me. When it comes to the chorus, that’s me doing Mantovani’s strings with guitars.”

Big rockstars always say the most exciting moment is that first breakthrough. Is that how Queen I felt?

“Yes. And thanks for calling me a big rockstar. I’m still a kid! I haven’t changed since those days. But it’s a good question. And the moment we felt it was that first Imperial College gig after the album was released. I’d been on the entertainments committee at Imperial College. We booked Hendrix to play in that big Union Hall, and I remember thinking, if we ever did anything like that, it would be incredible.

“Three years later, we’d booked it out, and from being a band that everybody walked past, suddenly we had an audience who actually wanted to hear what we did. Instead of people who grudgingly listened but really they’d rather hear us play covers – they were shouting out for our songs. That was an extraordinary moment. I remember that thought in my head: ‘There is a boulder rolling here…’”

- Queen I is out now via EMI.

Henry Yates is a freelance journalist who has written about music for titles including The Guardian, Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a talking head on Times Radio and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl and many more. As a guitarist with three decades' experience, he mostly plays a Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“Even the thought that Clapton might have seen a few seconds of my video feels surreal. But I’m truly honored”: Eric Clapton names Japanese neo-soul guitarist as one to watch

“You better be ready to prove it’s something you can do”: Giacomo Turra got exposed – but real guitar virtuosos are being wrongly accused of fakery, too