“I’ve never played a barre chord in my life. I hate them. You don’t need more than two or three notes to express a chord”: Andy Summers on his “abstracted instrumental” collabs with Robert Fripp, his dream pedalboard, and what he learned from Béla Bartók

It was the ’80s and Andy Summers was living the dream as guitar culture grew, and his side-project with King Crimson's mad-genius Fripp gave him the opportunity to work his art-house cinema influences into music

With their fourth album, 1981’s Ghost in the Machine, British new wave rockers the Police had laid the groundwork for their eventual domination of the global music scene, one that would see the group secure their status as the biggest band on the planet with 1983’s Synchronicity.

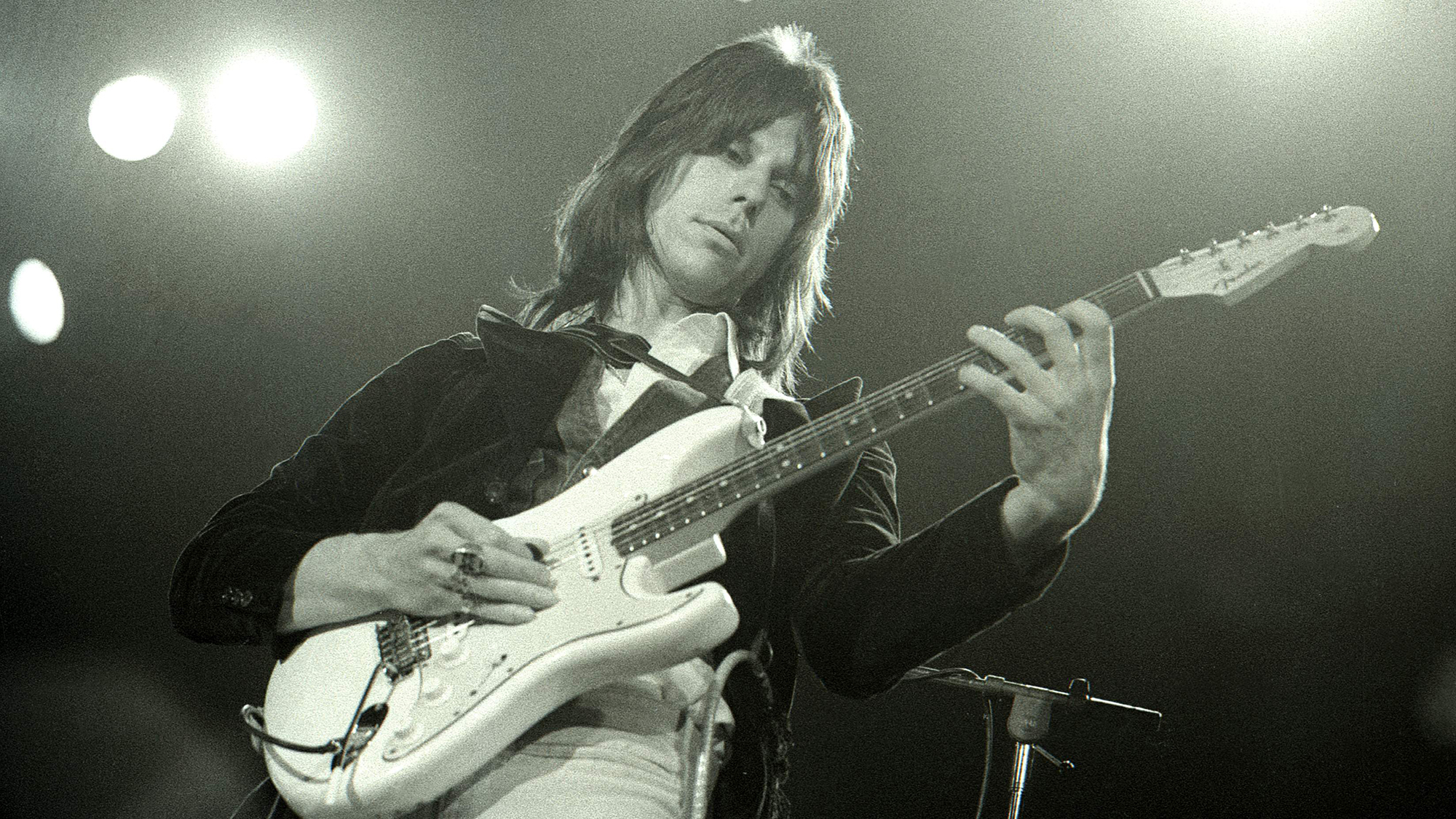

Inside the platinum-haired trio’s musical bubble, though, Andy Summers, their Tele-wielding guitarist, had a yearning to establish an identity in his own right outside of the confines of the Police.

“Establishing an identity was exactly what I was wanting to do,” Summers says today. “I’m not an insecure individual, but as you can imagine, we were so swamped by all the Police stuff – 24/7, year in, year out – that I sort of felt like I had to step outside of that for a minute and just do something with somebody else.”

Summers would team with King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp to record the first of two instrumental albums, beginning with 1982’s I Advance Masked. Experimental in spirit, I Advance Masked saw both guitarists exploring musical terrain in a free-form, improvisational approach with Summers fully embracing the incoming innovative technology of guitar synths.

The pair’s second and last outing together, 1984’s Bewitched, continued on this experimental route but was a lot more structured, concise and accessible, with Summers taking on a greater creative role with the album’s overall sonic palette.

“Making those albums with Fripp was kind of like a therapy thing for myself,” Summers says. “I mean, it was challenging to make those records, but they both came out pretty well, and I Advance Masked made it to Number 60 on the Billboard album chart, so that was kind of pleasing.”

You started using the new technology of guitar synths with the Police, particularly on 1980’s Don’t Stand So Close to Me. But you took a much heavier experimental approach on your two albums with Robert Fripp. Why is that?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“It was more instrumental, and I felt that because we were not playing behind a singer, we didn’t necessarily have to follow any type of song forms, so we pushed it all out a bit. And Robert was up for that, as he’s more in that direction anyway, so it was very natural to do that.

“As we weren’t trying to make pop songs, I began experimenting musically with a Roland MSQ-700 sequencer, a Roland TR-727 drum machine, a Yamaha DX7 synth and a Roland JP-6 [Jupiter 6] synth.”

I Advance Masked was free-form and unstructured in its compositional approach, especially compared to Bewitched, which adhered to a more structured form.

“Yes, but I can’t remember a lot of it off the top of my head, except that I ended up finishing it off on my own because Robert had to leave. Because of that, I had to produce it and do it all, too.”

I always had an ear open to new sounds, and to what was possible, when things like the Roland guitar synth turned up, I was into it right away

There’s one track on Bewitched – What Kind of Man Reads Playboy – where you seem to perfectly distill the state of the electric guitar in the mid ’80s.

“I was definitely living a full life and very prominently in the public sphere, if you like, of electric guitarists. I was enjoying it. I had my fantastic Pete Cornish pedalboard; I had all the devices, and we were very into it at that point.

“Everybody was into their pedals and stuff and was very into making new sounds. Pete Cornish was the sort of leading guru in making these beautiful pedalboards where he’d take all the shells off the pedals and all the electronics and put them together to hook it all up into this pedalboard.

“That was a major thing for me because I’d gone from the early days with the Police with, like, one MXR Phase 90 taped to the floor with a bit of Scotch tape to finally getting the very deluxe and the most desirable pedalboard of the time.”

Was the Pete Cornish pedalboard integral to your sound palette for the sessions?

“Absolutely – it was really important. It contained a couple of fuzz boxes, an envelope filter, some sort of reverb, an MXR Phase 90, a Roland chorus and an Echoplex for tape delay. I used it for about five years. Because I always had an ear open to new sounds, and to what was possible, when things like the Roland guitar synth turned up, I was into it right away.”

What guitar and amps did you use on the albums you did with Fripp?

“The main guitar on both was a 1961 Fender Telecaster through a single-speaker Mesa/Boogie. I also used a Guitarman electric 12-string, a Martin D-28, a Dobro and a National steel-string.”

Part of your signature style is the use of add9 chords with no major or minor third, which brings a kind of neutrality to the music.

“And very purposely so. I mean, a lot of things influence one in life, and you can point it back to where it came from, as I often cite Béla Bartók. I had studied Bartók at college, so it was sort of already in my bag, where you could express chords without using the minor or major third, but instead use the added second or the ninth.

“And this became very much a part of the style I used in the Police. I’ve never played a barre chord in my life. I hate them. You don’t need more than two or three notes to express a chord.”

Did your passion for photography directly influence your improvisational approach to the guitar on I Advance Masked and Bewitched?

When I was about 15 or 16, I was an obsessive guitarist. I lived for the guitar, then I went to see all these art-house films in my hometown. All those great European art directors made a big emotional impact on me

“By the time we recorded those records, I was way into photography; I was photographing all the time. It really started for me in 1979 when I was in New York and surrounded by photographers, and I started to get interested in it, but I think there’s an earlier seed to it. When I was about 15 or 16, I was an obsessive guitarist.

“I lived for the guitar, then I went to see all these art-house films in my hometown. These were all black-and-white films made by François Truffaut, Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman and so forth. All those great European art directors made a big emotional impact on me. So I think the emergence of this sort of lush photography – that’s where it really came from for me.

“I know at the time I was so knocked out by all these films that I thought I wanted to be a film director, but I was just too sort of caught up in the guitar. But later it sort of resurfaced for me in New York City, where I went and got a Nikon and started studying pictures and getting tips from other photographers. I got completely into it.”

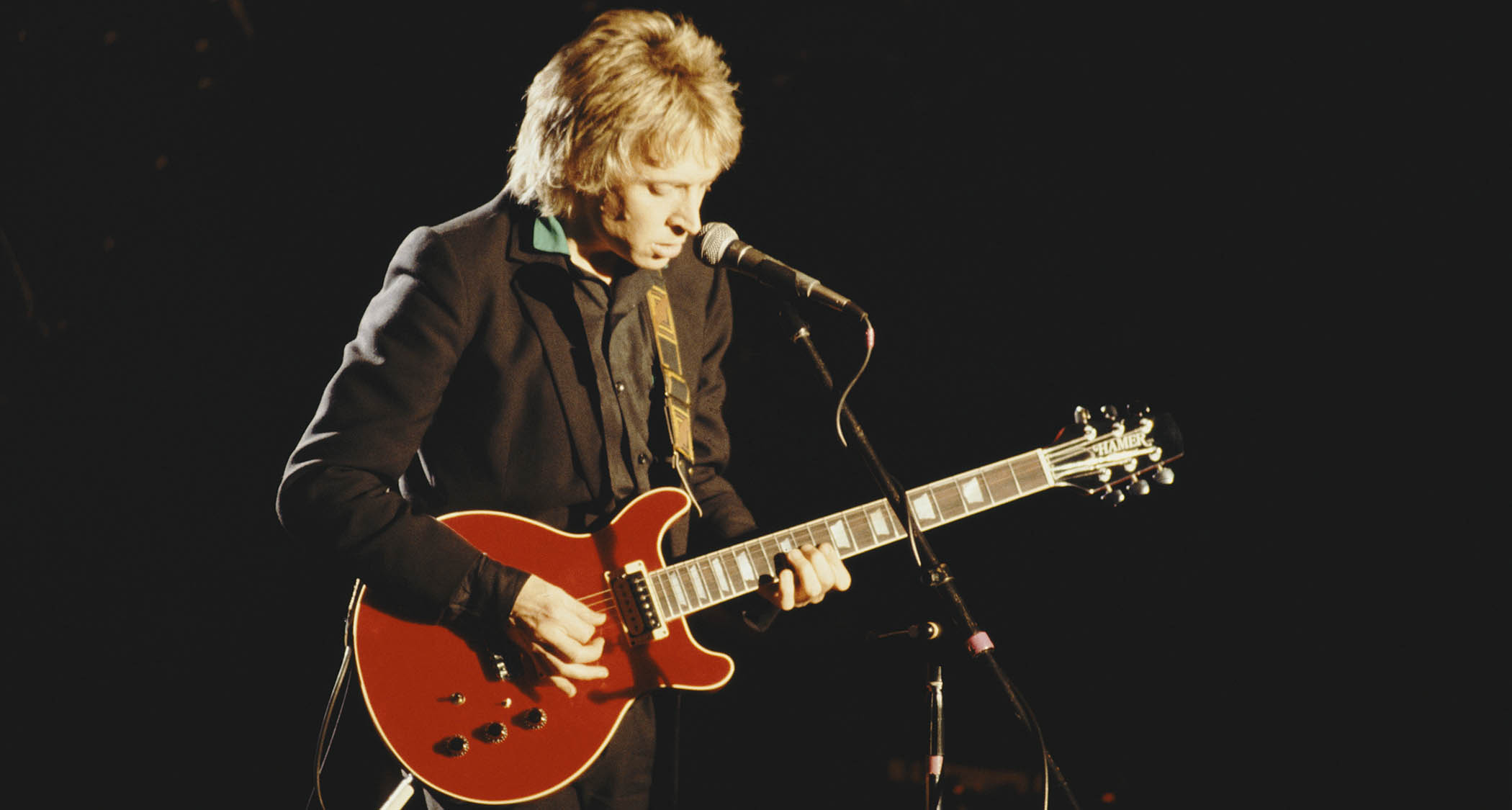

At the time of the Fripp collaborations, instrumental guitar music was starting to become a commercially viable option for labels who were happy to provide big budgets for it.

“Yeah, and it was wide open as everybody was trying to push the envelope with guitar sounds and styles. You had players like Joe Satriani and Steve Vai who were more in the rock vein and really hitting that guitar style that became extremely popular.

“On the other end, you had players like Adrian Belew who was more radical and sort of experimental. And that sort of made my style quite apparent with the way I approached music with the Police.

“The records I made with Fripp were a pretty kind of advanced style of guitar playing at the time, in that they were drawing from all sorts of sources. In other words, it was abstracted instrumental music.”

Joe Matera is an Australian guitarist and music journalist who has spent the past two decades interviewing a who's who of the rock and metal world and written for Guitar World, Total Guitar, Rolling Stone, Goldmine, Sound On Sound, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer and many others. He is also a recording and performing musician and solo artist who has toured Europe on a regular basis and released several well-received albums including instrumental guitar rock outings through various European labels. Roxy Music's Phil Manzanera has called him, "... a great guitarist who knows what an electric guitar should sound like and plays a fluid pleasing style of rock." He's the author of Backstage Pass: The Grit and the Glamour.