“Bluegrass and thrash are nearly the same – fast, precise, aggressive, melodic, with songs about death, destruction and doom”: Meet The Native Howl, the thrashgrass pioneers running Taylor acoustics through Mesa/Boogie stacks

The Native Howl’s Alex Holycross turned himself around after a suicide attempt, and focused on merging bluegrass with thrash – and spreading the word about giving and getting help when it’s needed

This article is part of Guitar World's series of interviews and features with artists addressing and raising awareness around themes of mental health, particularly as they relate to musicians.

The Native Howl have always had two goals: retain full control of their art, and create music as a means of expression and healing for themselves and their audiences.

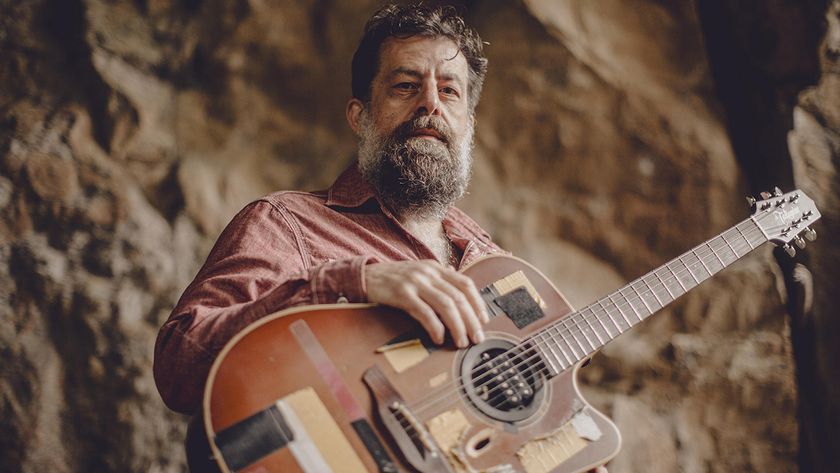

The band define themselves as “thrash grass” – a fast-and-furious blend of thrash metal and bluegrass. Over they years they’ve recorded, produced and released material independently, tracking at vocalist/guitarist/bouzouki player Alex Holycross’ Clean As Dirt Studios in Leonard, Michigan.

For over a decade they’ve been touring the U.S. on their own and as support for the likes of GWAR, Black Label Society, Airbourne and Corrosion of Conformity. They’re closing 2024 with Struggle Jennings and Clutch.

“This isn't a band as much as it is a family that plays music together,” says Holycross of his colleagues Jake Sawicki (banjo/vocals/harmonica), Mark “Chan” Chandler (bass/vocals) and Zach Bolling (drums/percussion). “I've known these guys for over half my life. We’ve done things our way – built our own studio and learned how to do everything ourselves – because we wanted the autonomy.”

As a result of Covid in 2020, The Native Howl, like many similar bands, were struggling. “We couldn’t function as before,” says Holycross. “We needed backup, resources, help. We needed business partners and mutually beneficial relationships.”

They auditioned for Season 1 of television reality series No Cover. Selected as one of 25 contestants from thousands of applicants, they spent two weeks in Los Angeles, made it to the finals, and won the contest and a recording contract with Sumerian Records. Their latest album Sons Of Destruction was recorded at Dave Grohl’s Studio 606 with acclaimed producer Jay Ruston.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Holycross credits No Cover with “saving the band and saving my life” – when the show came into his life he was six months sober from alcohol, after years of self-medicating his depression. Two weeks shy of his 18th birthday he lost his father to suicide. Other traumas led to him staging his own attempt.

Today, grit, therapy, music, and the support of his bandmates and friends see him through, along with the determination to use his platform for outreach and mental health awareness.

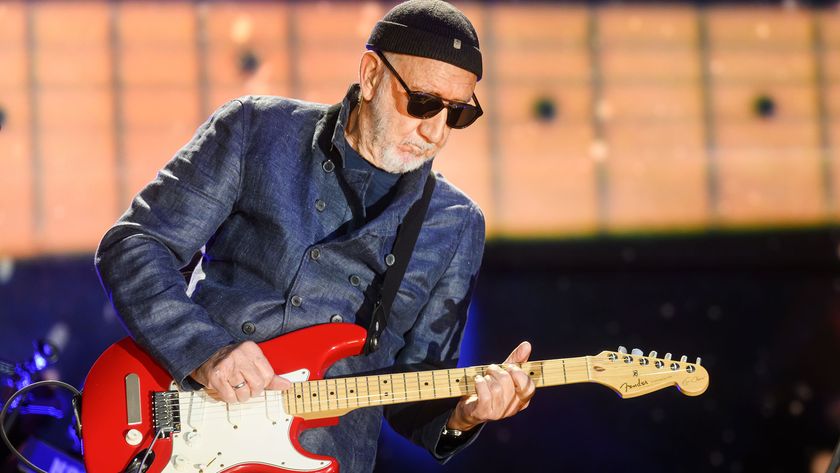

Nothing says “thrashgrass” like a Taylor T5z into a Mesa/Boogie Triple Rectifier.

“It's quite the sight seeing an acoustic guitar going through a full stack. It took a long time to figure out a rig that would work with this crazy idea of ours.

“It’s as if the T5z Custom and Pro were divinely designed by my guitar sponsor, Taylor Guitars, for this combination of thrash and bluegrass. Much of it is comprised of acoustic ‘cross strumming,’ a much more aggressive style of chopping chords.

“The linchpin is the T5z’s pickup switch, which allows me to toggle to a humbucker from the acoustic pickup when we go into our heavy riffs. I hit my AB switch from my Mesa Rosette to my Triple Rectifier, scream insanely into the microphone, and then we’ve arrived at the thrash part of the equation.”

How did the equation develop?

“Our band is unique in that a lot of our music is Chan holding the bluegrass element down, and switching between what we call the ‘root-fifth hop’ of bluegrass and virtuoso bass solos. Combined with Jake’s highly innovative banjo style, we’re locked in.

I realized bluegrass and thrash are nearly the same – aggressive, melodic, with songs about death and doom

“We know what every person is playing at all times. That gives Zach, Chan and Jake carte blanche to be free and create the wildest, most beautiful sounds I’ve ever heard.”

Were your roots always in bluegrass and metal?

“I was a thrash metal kid, but in 2014 I went to the Wheatland bluegrass festival in Michigan. I had limited experience with bluegrass music or the culture around it, but I realized bluegrass and thrash are nearly the same – fast, precise, aggressive, melodic, with songs about death, destruction and doom.

“I was motivated to write the fastest, meanest thing I could think of. That became our first Billboard hit, Thunderhead, and that’s how thrashgrass began.”

Sons of Destruction captures your live energy in a studio setting.

“We attempt to do things as live as possible. We’re very strict during writing and rehearsals, so that by the time we record the songs have become second nature. It is organic because of all the front-loaded work we’ve put in. We play the songs a million times, go back and forth on riff composition and vocal harmony, so when we get to the final sessions, it’s just that: live.”

You once said that if you could have five minutes with James Hetfield and Chris Cornell, you’d thank them for “instilling in me the ability to transform pain into art.”

“And now, especially, Maynard James Keenan. Their music saved my life. Pain and darkness consume me – as they do many of us – and I shed that darkness by writing songs. That’s how I let it go. That’s what I write about because that’s what I know.

“But much more importantly, it’s for people who feel pain and sadness, to let them know that their struggle is not theirs alone. If only one person hears a song that’s filled with these difficult topics and it stops them from doing something irreversible then everything we’ve done is worth it.

“Making music isn’t about money and all that insane rockstar shit. That’s nice, sure; but music is really about connecting with and helping people. That’s the goal. That’s why we’re here.”

You’re four years sober from alcohol. What are you comfortable sharing about your recovery?

“I drank to numb my pain, to quiet the nagging, lying voice in my head that told me I couldn’t overcome my past, that I couldn’t make it through what I’d been through. I never drank to the point of hurting anyone. I never drank and drove. I didn’t drink for fun or to celebrate anything. I drank to stop the hurt.

You have to quit drinking, figure out why you were drinking, and fix that. It’s hard work

“It started when I was 15, just having beers on the weekends. It wasn’t daily until I was 28; and for two years, from 28 to 30, there was not one day that I didn’t drink. I was such a pro at it that I never blacked out. I knew exactly how much to drink every night to numb the pain, but not to where I couldn’t function.

“I knew I had to quit, and I quit on my own. But I realized I was still distraught, and drinking wasn’t the disease – it was a symptom of the disease. I went to therapy. You have to quit drinking, figure out why you were drinking, and fix that. It’s hard work. But the most powerful thing you can do is accept your weakness and face it head-on, with the tools and help you need.”

Mental health challenges are at crisis level, yet we continue to deem these topics – particularly suicide – as inappropriate for discussion.

“It’s like a cultural faux pas. We step back; yet if you don’t talk about it, how do you fix it? But you can’t bring it up, because everyone gets uncomfortable. There has to be an open dialogue, so people can feel comfortable and safe enough to talk about it and know they’re not the only ones.

“There is no darker topic than suicide. It’s considered taboo because people who haven’t been through this hell don’t know how to comfort others in their darkest hours. We need to drop the stigma so that people know how to help adults, and most importantly kids, who struggle with this.

“We need to connect. People need to be educated on the mindset of those who suffer. There needs to be discussion about how to help people, and how to get people the help they need.”

Where are you in your healing?

“I’m okay. I had ideation on and off for years and I drank to numb that, amongst other sadness and trauma. I attempted once, and I thank God that I stopped myself and I’m still here and able to have this conversation about it.

“Through extensive therapy, the support of friends and family, and the grace of God, I’m still alive and still fighting. I’m here and blessed to play music with my brothers for a living.

“That’s why I’m so passionate about it, and why I talk and sing about the struggle of existence, of fighting off these bad thoughts. People keep their mouths shut and tragedies happen. We should be able to speak about these things. It behooves us to create an open dialogue and encourage people to take care of themselves and others.”

Mental health resources

Alison Richter is a seasoned journalist who interviews musicians, producers, engineers, and other industry professionals, and covers mental health issues for GuitarWorld.com. Writing credits include a wide range of publications, including GuitarWorld.com, MusicRadar.com, Bass Player, TNAG Connoisseur, Reverb, Music Industry News, Acoustic, Drummer, Guitar.com, Gearphoria, She Shreds, Guitar Girl, and Collectible Guitar.

“You got it!” Rare footage of Andy Summers teaching John Mayer how to play Message in a Bottle surfaces online

“I was very inspired by my Ibanez sister and the way she approaches her songwriting and her chords”: Nita Strauss reveals how Yvette Young inspired one of her favorite riffs she’s ever written