“Freddie King would ask me why I never tried using thumbpicks... I really like digging in with my fingers”: He replaced Jimi Hendrix in Little Richard's band, was idolized by Stevie Ray Vaughan, and is one of the most underrated Tele slingers of all time

Extracting inimitable, stinging tone from his Tele with just his fingers, Albert Collins carved a hugely influential sonic path for himself, though he's still often left out of discussions of the greatest blues guitarists of all time

It's a sweaty, booty-shakin', chick-chasin', money-wastin' Saturday night at Tramps, a Manhattan R&B/zydeco club that comes about as close to a down-home N'awlins/Houston juke joint as New York gets.

No pretensions here. These thirty something yupsters are throwing down heartily after a hard day's work on Wall Street. Power ties are removed, and correct blazers are peeled and draped around chairs as patrons knock down shots of tequila and bottles of Corona before heading for the dance floor.

It's all about letting loose, blowing off steam, getting wild and crazy. And there is no better band to fan the flames of this party than Albert Collins and the Icebreakers.

The band kicks it off. Behind the drums, Sokol Richardson, the big, bad-looking dude with the clean head and cool hat, thumps out a shuffle that this crowd can't resist. Johnny B. Gayden, an Icebreaker from way back, jumps on that groove and grins knowingly as he locks in tight with the bass drum.

The pulse causes certain inebriated patrons to lose what's left of their inhibitions. A few are clapping on 1-and-3, but that's cool – this ain't nothin' but a party and no one cares if you act the fool.

Second guitarist Debbie Davies is feeling the groove. A slick player with some serious blues chops of her own, she's comping funky 7th chords and laughing loudly as the giddy dancers fall all over themselves.

Next to her is a formidable line of funky hornpower, courtesy of New York's own Uptown Horns – Bob Funk on 'bone, Paul Litteral on trumpet, Crispin Cioe on alto sax, and the mysterious man in the shades, Arno Hecht, on tenor sax.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Alongside these hardest-working-men-in-showbusiness is Icebreaker Chuck Williams, whose special gift is an ability to play two horns simultaneously, a la Rahsaan Roland Kirk. Then, off on the other far side of the stage, lurking behind some keyboards, is Eddie Harsch, laying down a velvety B-3 cushion that fattens the groove as it soothes the soul.

When this band kicks in (along with the tequila), you know you've been kicked. Steamrolled, is more like it.

Finally, after three pulse-quickening warmup numbers, emcee Williams grabs the mic and takes the excitement level up a notch: “Ladies and gentlemen, get ready for the man... The Master of the Telecaster... The Houston Twister... The Razor Blade... The Iceman himself... ALBERT COLLINS!”

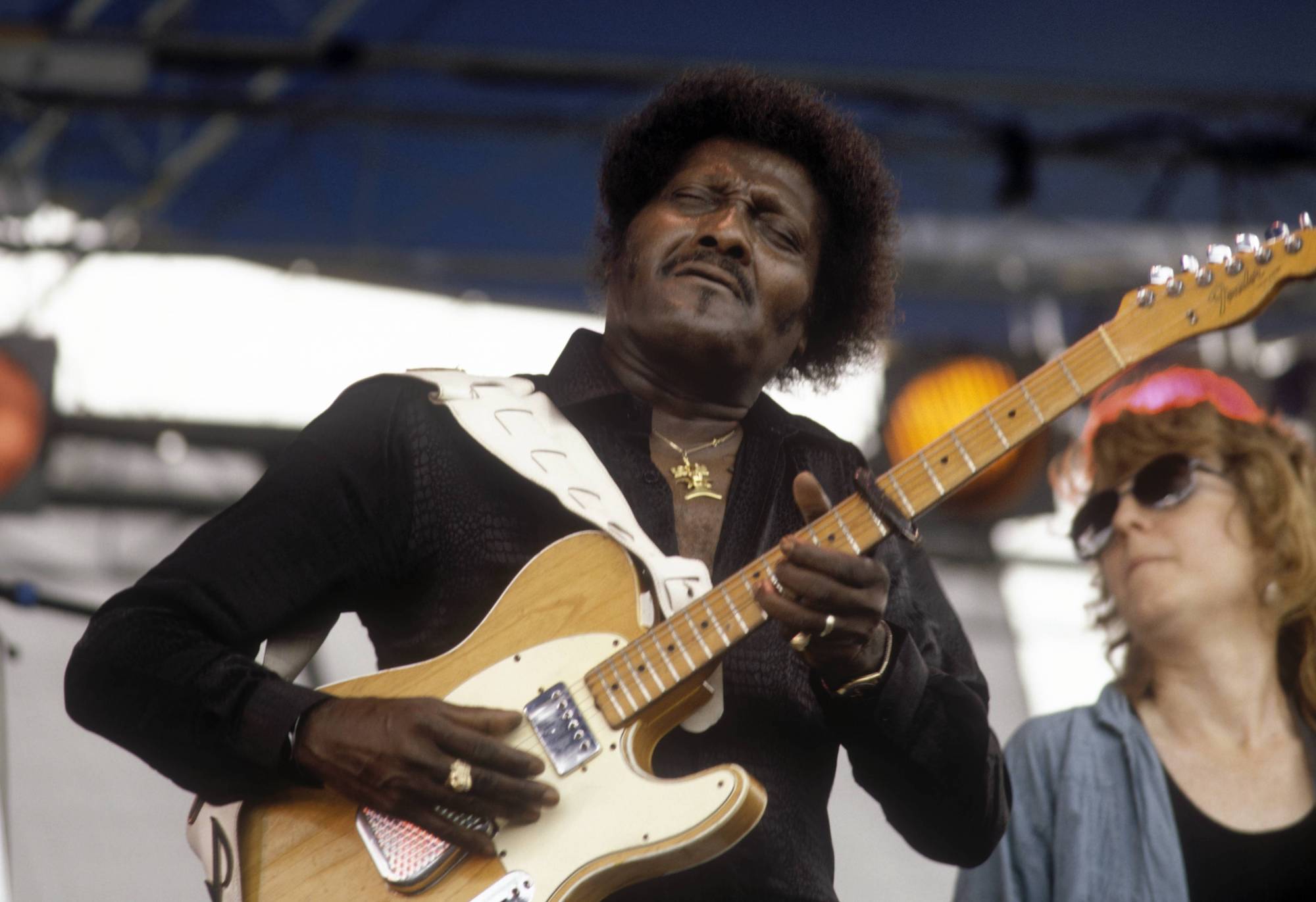

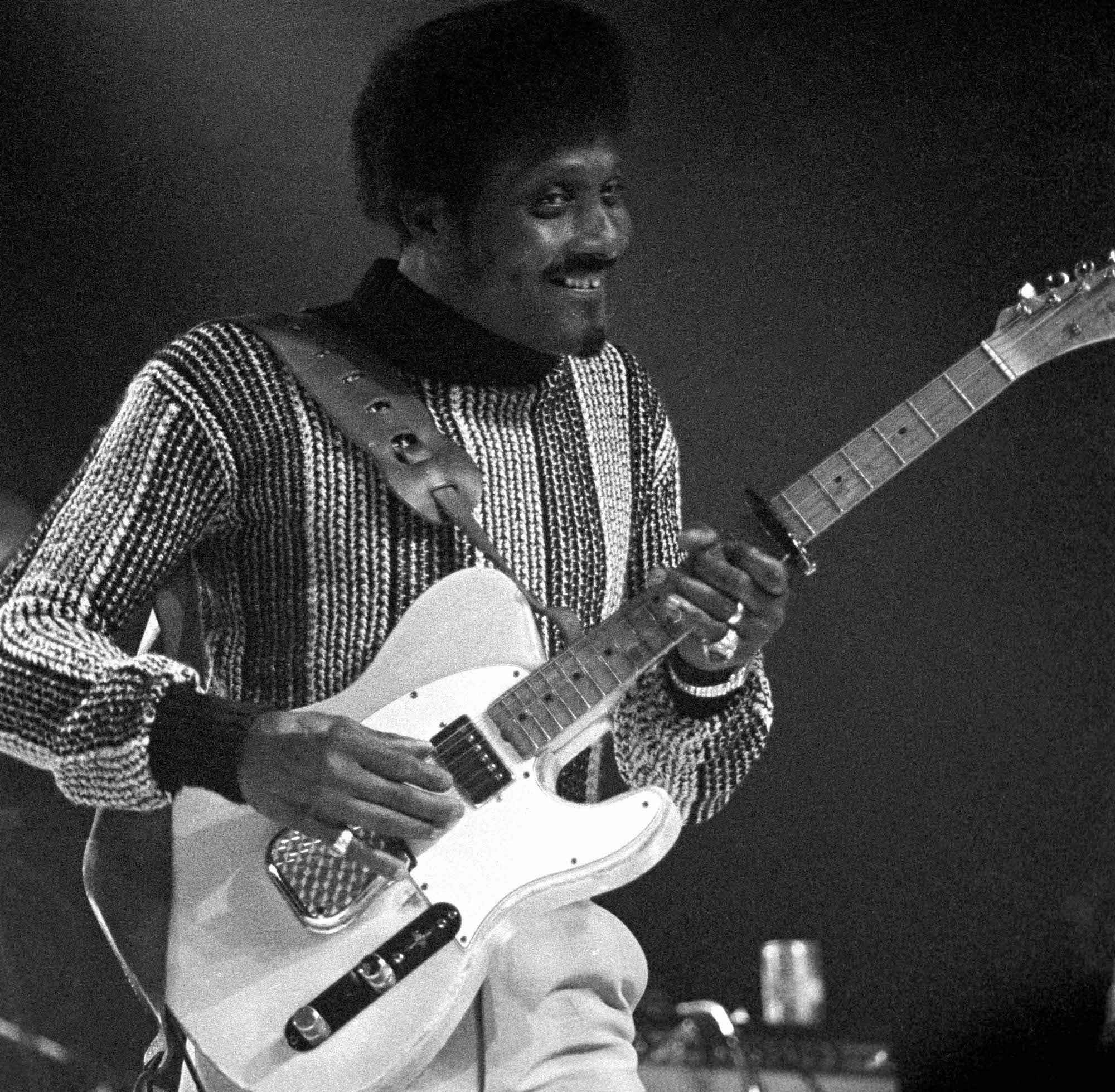

Lean and young-looking for his 58 years, he strides onto the stage with his blonde '61 Tele slung, gunslinger-style, across his right shoulder. He plugs into the Fender Twin, cranks everything up to 10, catches the groove and digs in.

The sound leaps from the house PA and shoots up your spine. That tone! There is simply nothing else like it on the planet. One note and it's all over. Killer, killer tone.

Now Albert is prowling the stage, mock scowling at the crowd. It's his “game face,” the same kind of bad-ass look Ali used to flash at Joe Frazier during weigh-ins.

He stalks, pauses, glares at the crowd as if to say, “Take this,” then cuts loose with that piercing icepick tone. Several guitar players in the house nearly drop to their knees, wincing in mock agony at the sheer intensity of Albert's onslaught.

The dancers laugh and spin on the dance floor. They don't know from guitar technique or chops or speed licks, but they do know a good groove when they feel one.

Now Albert grabs the mic and addresses the pent-up house: “This here's my first million seller... and I still ain't been paid yet!” He digs into Frosty, the funky instrumental he cut back in 1962 for a tiny Texas label, HallWay. That 45 did, in fact, sell a million and has since become Albert's signature song.

A catchy funk-shuffle in the vein of his other early Sixties hits, like Sno-Cone, Icy Blue, Frost Bite, and Thaw Out (all of which can be heard on the fine compilation album, The Cool Sound Of Albert Collins, released a few years ago on the West German Crosscut label), it caters to the dancing fools as it thrills the aspiring guitarists in the house.

The party continues as Albert sings the hilarious (and appropriate) I Ain't Drunk (I'm Just Drinkin'). And when the band eases into a molasses-slow blues, the revelers emit an empathetic sigh as Albert lets his Tele do the talking.

Downstairs in the Tramps musicians' lounge, following an energized set that sent everyone home tingling, Albert welcomes the well-wishers flooding into his dressing room.

Propped in a corner nearby is his notorious axe, the same one he's been playing steadily, ten months a year, since 1969.

A capo is secured in place at the seventh fret; occasionally, he'll move it up to the tenth fret. He doesn't really need the whole neck. This ain't fusion music. No scales, arpeggios, and octave leaps are required for earthy material like Too Many Dirty Dishes, A Good Fool Is Hard To Find, or Lights Are On But Nobody's Home.

After this gig, Albert and the band will be heading to Europe for a tour and recording session. The big news is that, after seven albums, he's left Alligator Records. He's been signed by Virgin UK and stands to become the biggest star in their roster for Point Blank, a new blues subsidiary label that will also feature the fresh sounds of The Kinsey Report and a new blues discovery out of Detroit, Larry McRae.

Something is definitely in the air, and Albert is at its forefront. There's a new blues boom happening. And as was the case 20 years ago, it appears to be generated from the UK.

Twenty years ago, young blues-loving Brits like John Mayall, Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Peter Green were spreading the news about blues. By covering tunes by Howlin' Wolf, Muddy Waters, and John Lee Hooker, they got a generation of Yanks to look in their own backyards for genuine blues treasures. Stateside, young guitar stars like Johnny Winter and Michael Bloomfield were also trumpeting the cause of blues titans like B.B. King, Buddy Guy, and Otis Rush.

One name that seems to have gotten left by the wayside in that first blues renaissance, a generation ago, is Albert Collins. But what goes around comes around, and 1990 promises to be his biggest year ever.

Earlier this year, Albert made a guest appearance on Jack Bruce's fine Epic album, A Question Of Time, doing his icepick thing on a cover of Willie Dixon's Blues You Can't Lose.

A few months later, he made a cameo on Gary Moore's Charisma album, Still Got The Blues, going toe-to-toe with the Irish axe slinger on a killing rendition of Johnny Guitar Watson's Too Tired. And now comes the big Virgin/Point Blank debut, featuring the same smoking band that worked the crowd at Tramps that hot Saturday night.

At press time, the album (due out in September) was as yet unnamed, though Albert is leaning towards Freezer Burn. The Master of the Telecaster has high hopes for this one.

“Yeah, man,” he laughs. “I hope it goes over big, I really do, man. It's about time.”

Albert certainly merits the status accorded, say, B. B. King. He's been at it a long time now, but it's only been within the past few years that he's made any kind of commercial inroads in terms of high-visibility and recognition.

There was the Grammy Award in 1987 for Showdown! (Alligator), his blues summit meeting with Robert Cray and fellow Houstonite Johnny “Clyde” Copeland. There was his 1985 TV appearance at the monumental Live Aid concert in Philadelphia, where he jammed alongside George Thorogood before a worldwide viewing audience estimated at 1.8 billion.

He followed that up with a guest spot on David Bowie's Underground single from the soundtrack of the fantasy film Labyrinth, and a scene-stealing cameo appearance in the film, Adventures in Babysitting .

Few connoisseurs of higher culture will ever forget the Seagram's Wine Cooler commercial in which Bruce Willis struts into a bar, a girl on each arm, as Albert does his thing on stage. Yeah, the Iceman's getting hip to marketing.

Born in the tiny Texas town of Leona (population 165) on Oct. 1, 1932, Albert and his family moved to the big city of Houston when he was nine. There he grew up in the city's Third Ward area with fellow future guitarists Johnny Copeland and Johnny Guitar Watson.

Though Albert started out by taking piano lessons, he eventually got turned onto guitar by his cousin Willow Young, who presented him with an Alamo acoustic and a smattering of lessons.

“As soon as he gave me that guitar and showed me a few chords, man, I forgot all about piano,” Albert recalls.

His cousin was playing with an open tuning at the time. “I just got that tuning and I ran with it.”

I used to see Freddie King around Texas and he'd ask me why I never tried using thumbpicks, but I just couldn't play with one

Over the years, he has alternated between E-minor and D-minor tuning. That, plus the capo at the seventh fret and his viciously percussive, fingers-on-strings, right-hand attack, gives Albert a distinctive sound that is instantly recognizable and virtually impossible to copy.

“When I started out playing, I tried to have my own sound,” he explains. “I used to hear B.B. and T-Bone Walker and Guitar Slim and them guys, and I always thought I'd avoid that sound and go after my own style. The minor tuning helped. So did the capo, which I started using after I met up with Gatemouth (Brown). He was a pretty big influence on me back then.

“Gate was kind of a big star back in the Fifties, so he wasn't never around that much. But when I did see him, we'd always have a little talk about music and playing.

“As a matter of fact, I was playing an Epiphone hollow box for a while until I first saw Gate playing a Fender Esquire. So I went out and bought me an Esquire in 1952. I had that for a while and later on I got me a Telecaster, which I've played ever since.”

Another big influence on Albert in his formative years was his other cousin, famed Delta master Lightnin' Hopkins.

“He was kin to me on my mother's side,” Collins says. “I'd been around him since I was a little kid. He used to come to my mother's house and we'd go over to their house for dinner sometimes. So I got a chance to watch him up close and ask him questions. And he'd play the Juneteenth Festival every year. I'd always be around when he was playing. He was one of my first influences.”

The first song Albert learned on acoustic was John Lee Hooker's Boogie Chillen'. As he progressed from acoustic to hollowbody to the Fender Esquire, he began developing his patented icepick sound, playing with flesh-on-steel rather than with picks.

“I tried using picks two or three times, man. I just don't like picks. I used to see Freddie King around Texas and he'd ask me why I never tried using thumbpicks, but I just couldn't play with one. Picks will make you fast, though. But I really like digging in with my fingers.”

Albert began his professional career in 1950, when he formed his first band, Albert Collins and the Rhythm Rockers, an eight-piece group that played around the Houston club circuit.

“I was really into the big band sound then,” he recalls. “Stuff like Jimmie Lunceford and Tommy Dorsey, you know, with all the horns. And, of course, we were also drawing on cats like T-Bone and Wynonie Harris for this band.”

The alto player in the Rhythm Rockers, Henry Hayes, was a schooled jazz musician who offered young Albert several tips on the rudiments of jazz.

“Actually, there was a time when I was trying to play jazz,” he says of the period he spent in Kansas City around 1966.

“I got kinda confused about what I wanted to do. I started wantin' to play like Grant Green and Kenny Burrell and them cats. I played there with an organist by the name of Lawrence Wright, and was listening a lot to cats like McGriff and George Benson and Wes Montgomery.

“I actually met Wes before he died. So I was going through this jazz phase there in Kansas City, but I finally decided it didn't fit me, that I should stick with the blues.”

Albert cut his first single back in 1958 for the Houston-based Kangaroo label, co-owned by his alto player, Henry Hayes.

That 45, The Freeze (backed with Collins Shuffle), set the tone for a series of funk-blues instrumentals to follow. That tune brought Collins some local notoriety, and he was soon sharing bills with his idols, Gatemouth, T-Bone, and Guitar Slim.

Two years later, he cut the funky DeFrost (backed with Albert's Alley) for Hall-Way Records, a small blues and rock and roll label based in Beaumont, Texas.

Albert recalls two local youngsters hanging around the studio during his recording session there.

“Johnny Winter and Janis Joplin were there,” he says. “Johnny must've been 16 years old and his brother Edgar was just a little kid then. And Janis wasn't singing then but she really dug the music.”

Another youngster Albert met back then was a slim teenager by the name of Jimi Hendrix.

“I first met him when he was 17 years old. A few years later I took his place in Little Richard's band. Yeah, Jimi was playing blues back then. Blues and R&B. This was before he got psychedelic, ya understand.”

All during the Sixties, while he continued to cut sides for small Texas labels like Great Scott, Brylen, and TFC, Albert maintained a day gig in Houston.

At various times he worked as a delivery man for a paint company, a truck driver for a furniture company, and a tractor driver on a ranch. His situation took a radical change in 1968 when Bob Hite, a noted blues archivist and lead singer with Canned Heat, travelled to the Ponderosa Club in the rough Third Ward area to catch Albert's act.

Knocked out by Albert's killing tones and unbridled conviction (not to mention his crowd-pleasing tactic of leaping into his audiences and beyond to the parking lots with a 100-foot cord, a little trick he picked up from seeing saxophonist Big Jay McNeely strolling through the audience with his horn back in 1953), Hite took Albert to California, where Eli Bird immediately signed him to Imperial Records.

Albert soon became an attraction at hotspots like the Fillmore and Matrix in San Francisco, and the Ash Grove in Los Angeles. The blues boom was in full swing on the West Coast, and Albert was right on the scene.

“Yeah, man, that's when I started meeting people like Frank Zappa and Bill Graham, Duane Allman and Grand Funk Railroad. There was a lot of jamming going on then.

“I hung out with Jimi and his Experience band. I played with him at festivals and we were getting ready to do a little tour together. But just after we talked about it, he died.”

Albert recorded three albums for Imperial (the best material from that period has been collected on the 1986 Charly compilation, Ice Cold Blues) before switching to the Denver-based Tumbleweed label run by Eagles producer Bill Szymczyk, who recruited Joe Walsh to produce one of Albert's singles for the label.

There followed a severe recording dry spell for Albert, though he continued to work hard on the road, traveling up and down the West Coast club circuit and appearing at all the major blues festivals around the country.

During this period, Albert toured alone, picking up top-flight accompanists like the Fabulous Thunderbirds and the Robert Cray Band from gig to gig. He also found time to cut guitar tracks behind Ike & Tina Turner on The Hunter (Blue Thumb), though his work went uncredited.

Phase Two in his career began in 1977, when blues hound Dick Shurman brought him to the attention of Chicago's Alligator Records, which in 1978 released the great Ice Pickin'.

Albert continued to prosper on Alligator through the Eighties, cutting such exemplary albums as 1980's Frostbite, 1981's Frozen Alive!, 1983's Don't Lose Your Cool, 1984's Live In Japan, 1986's Grammy-winning Showdown!, and the brilliant 1987 swan song on Alligator, Cold Snap, which reunited Albert with his boyhood idol, organist Jimmy McGriff.

“Man, I used to wanna be just like McGriff,” he says. “There was a time when I even bought me an organ. And what happened was, I got it stolen from me out on the highway one night, so I never tried to mess around with no organ no more.”

Luckily, since losing his organ, Albert has been attacking his Tele with a vengeance, curling toes and tingling spines from Houston to Holland and Oklahoma to Osaka. And now, with Virgin/Point Blank gearing up for a big push, the Iceman is poised on the brink of Phase Three of his long and illustrious career. His plans for the upcoming Virgin/Point Blank debut?

“Well, it's still blues but it's kinda more funk blues. It's a little bit more updated, you know. Closer to what James Brown was doing. Ain't too fast and ain't too slow. And I'm using a couple of girl singers on some of the tracks. I always liked girl singers.”

Will his guitar tone change at all?

“No, man. That's my sound. That hasn't changed too much over the years. I still try to keep my sound, to let people know that this is Albert Collins, you know?”

One note and there's absolutely no doubt. Whether it's a David Bowie cut, a Jack Bruce album, a Gary Moore project, a John Zorn project (check out his sizzling guitar work on the 14-minute Two Lane Highway from the 1988 Elektra/Nonesuch album, Spillane) or a Seagram's Wine Cooler commercial, there's no mistaking the touch of the Master.

This feature originally appeared in the September 1990 issue of Guitar World.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.