The Beatles' Revolver: a comprehensive guide to the guitars and recording equipment the Fab Four used to make the landmark album

GW dissects the album that changed the band's musical trajectory, and that of pop music as a whole

The following feature on the Beatles' Revolver first appeared in the Holiday 2011 issue of Guitar World.

Revolver is the album that made the Beatles recording artists in the absolute sense of the term.

Their previous six albums had demonstrated John Lennon and Paul McCartney's increasingly ambitious songwriting skills and the group's competence with a range of musical styles. But the productions, while strong, were undistinguished. Apart from some reverb, compression and EQ, the instruments and vocals were recorded in a wholly representational manner.

But even as early as 1963, while recording With the Beatles, the group's members had begun asking why their instruments and voices couldn't sound like something... else.

"Can we have a compressor on this guitar?" George Harrison had asked Norman Smith during the recording of his song Don't Bother Me in September of that year. "We might try to get a sort of organ sound."

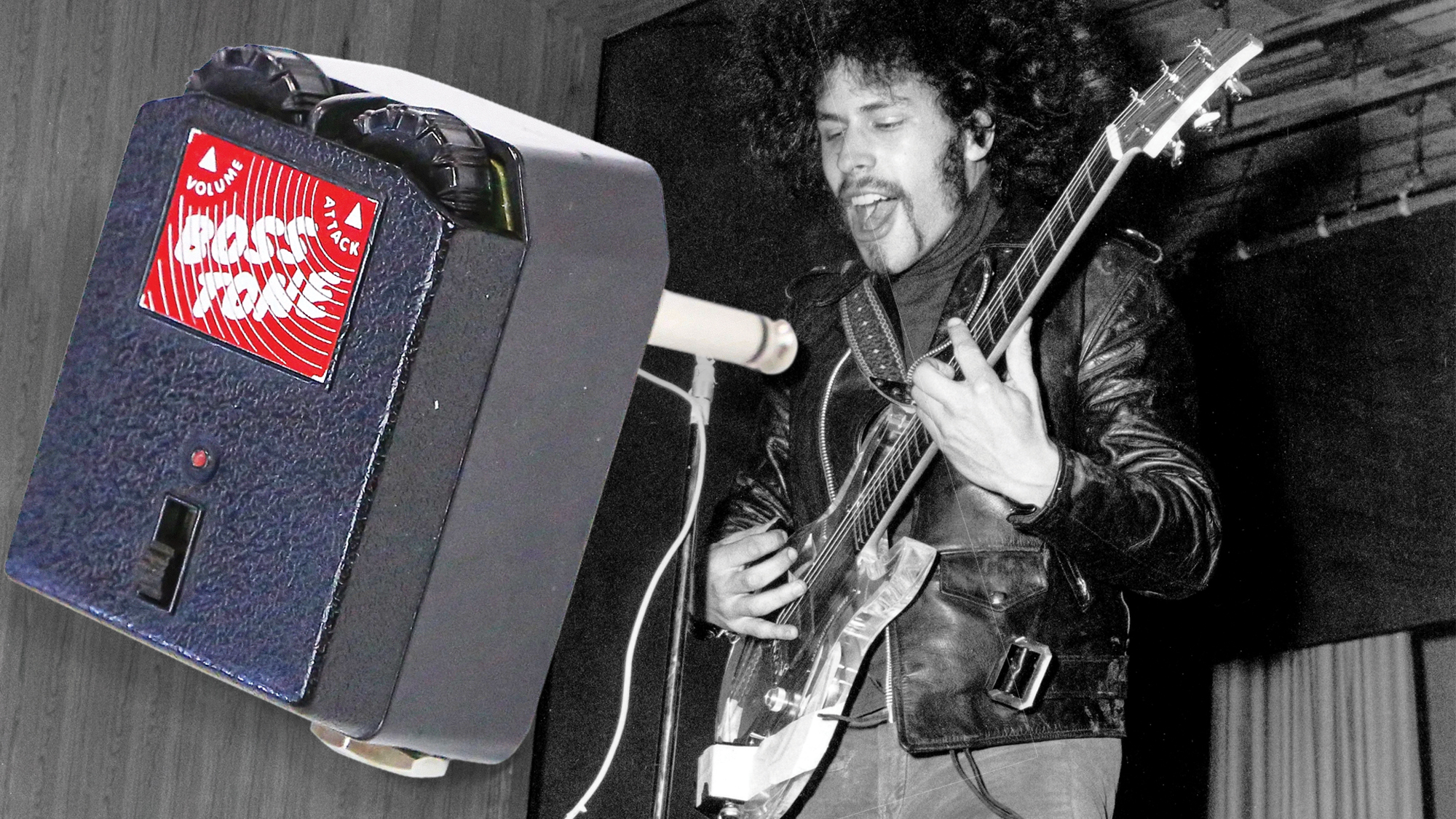

At the same session, Lennon had been voted down by George Martin when he plugged into a Gibson Maestro Fuzz-Tone. By 1966, no one, not even George Martin, could hold back the Beatles' musical ambitions. Not only was their music changing; their consciousness was expanding, courtesy of experimentation with pot and LSD. This synchronism would culminate, creatively, in Revolver, the only album the group released that year. But what an album it was.

From its inception, Revolver was designed to be an exploration of sound as it had never been heard before in pop music.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

And no one, apart from the Beatles themselves, was more instrumental to that end than 20-year-old Geoff Emerick, who engineered Revolver and created its many groundbreaking sounds. Emerick had served as tape operator on a number of Beatles sessions with Norman Smith, during which time he had become friendly with McCartney.

When Smith quit working with the group to become a record producer at the start of 1966, Emerick was asked to become the Beatles' engineer over some of his more qualified colleagues. "I suspect Paul had something to do with that," Emerick says. "We got along well, and I was young, so he knew I would be open to the kind of experimentation they wanted to do."

Though shy and quiet, Emerick was rebelliously disdainful of EMI's strict policies, which forbade microphones to be placed closer than 18 inches to drum kits and discouraged the overloading of audio signals to create distortion and "unnatural" sounds. On Revolver, Emerick systematically broke one rule after another in his efforts to give the Beatles the new and unusual sounds they demanded.

"I've always thought of sound as images rather than in strict technical terms," Emerick explains. "A lot of the sounds I heard in my head were dark, with more depth. And with Revolver, it was more about making things sound different, rather than real."

The new direction was evident from the very first track recorded: Tomorrow Never Knows. Titled simply Mark 1 at the time recording commenced on April 6, 1966, the song was written by Lennon, the product of his experience with LSD, which he'd taken the previous January.

Using lines from The Psychedelic Experience, an LSD manual based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, he wrote the song as a mantra composed of one repeating melody line over a driving bass and drum track. "It's only got the one chord, and the whole thing is meant to be like a drone," Lennon told Martin and Emerick.

Additionally, he explained, he wanted his voice to sound "like the Dalai Lama chanting from a mountaintop." Says Emerick, "I was thinking, Well, I've got an echo chamber and... that's all! I didn't know what I was going to do. And suddenly, there it was, staring me in the face!"

"It'' was the studio's Leslie rotary speaker cabinet, a standard piece of equipment for organs but one that had never been used for any other instrument or for voice.

As Lennon's voice came swirling through the Leslie, the assembled group listened in awe from the control room. "It's the Dalai Lennon!" exclaimed McCartney.

Emerick also showed his ingenuity in recording the song's drums to achieve the "thunderous" sound Lennon had requested. In addition to moving the mics right up to the drum heads (earning him an EMI reprimand for "microphone abuse"), Emerick applied a heavy dose of compression using a Fairchild 660 limiter to give the drums a very forward, "pumping'' sound.

"What on earth did you do to my drums?" Ringo Starr asked Emerick. "They sound fantastic!" (Emerick would go on to use close-miking elsewhere on the album, including for the horns on Good Day Sunshine and the strings on Eleanor Rigby.)

The day after Revolver's groundbreaking debut session, Tomorrow Never Knows was completed with another unusual technique: an overdubbing of tape loops assembled by McCartney, featuring distorted guitar and bass tones and sound effects. Tape loops had long been used in composition by avant-garde composers, but for the pop music world, it was entirely new.

For all of Emerick's sonic trickery, one of his greatest achievements on Revolver was his work on the Beatles' guitar tones. Over the past year the group had been unhappy with their guitar sounds, especially with the lack of presence.

For Revolver, they had some new and powerful amps to work in their favor, including a cream-colored Fender Bassman (intended for McCartney but appropriated by Harrison), two new blackface Fender Showmans with 1x15 cabs, and 120-watt Vox 7120 guitar amps.

New guitars for the sessions included Harrison's recently acquired 1964 Gibson SG Standard, his main guitar for Revolver, and Lennon and Harrison's sunburst Epiphone Casinos, a model that McCartney had owned for some time and also used on Revolver (Harrison's and McCartney's models had vibratos; Lennon's had a trapeze tailpiece).

Lennon also used a Gretsch 6120 during the recording of Paperback Writer on April 3, and he and Harrison might have used their Sonic Blue Fender Stratocasters, acquired in 1965 during the making of Help! McCartney, for his part, relied on his Rickenbacker 4001S bass, which he had received in the summer of 1965.

But Revolver's guitar sounds aren't simply a product of the Beatles' gear. Again, it's down to Emerick's touch with, once again, the Fairchild 660 limiter.

"It added a lot of presence," Emerick says. "Even if you just plug it in and use its circuitry – it sounds like the best tube amp ever."

To record Revolver's guitars, Emerick used his beloved Neumann U47 tube mics. These, however, he kept well away from the speakers, "normally about a foot, 18 inches away." This, he says, is where the magic arrived. "That's where it sounded good."

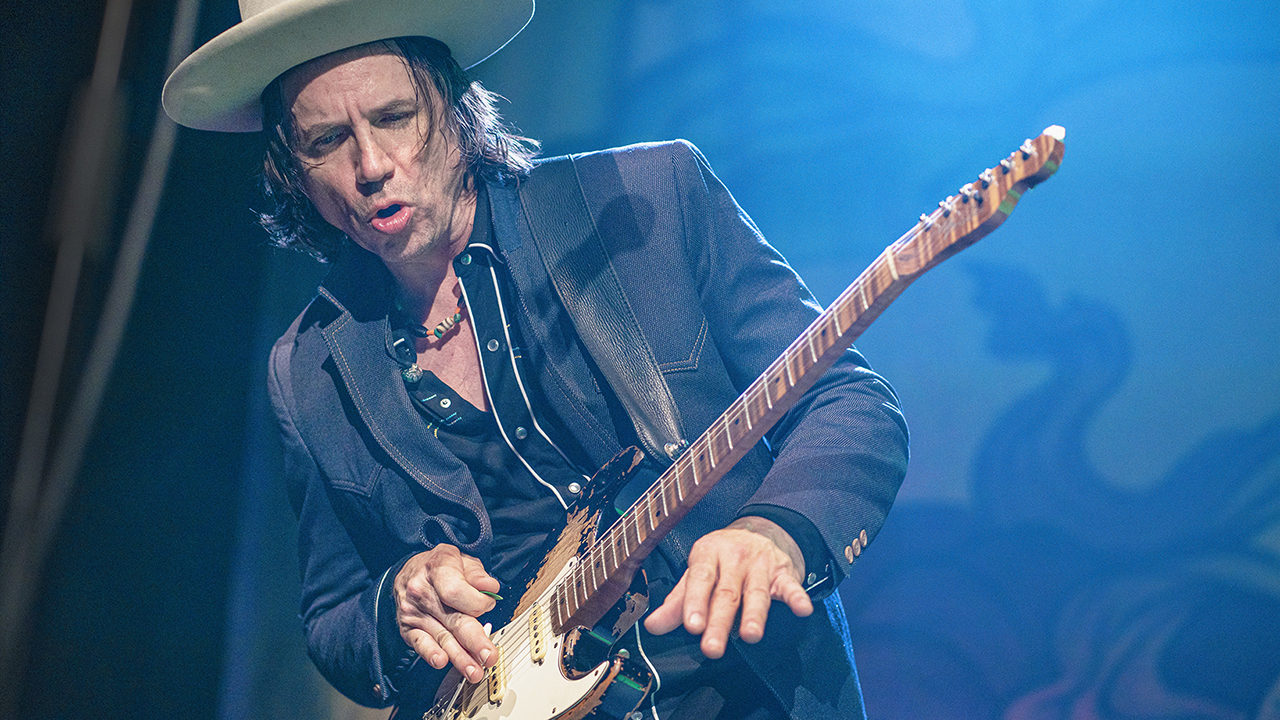

The payoff of his efforts can be heard all over Revolver tracks like And Your Bird Can Sing, She Said She Said and, especially, Taxman. The Harrison-penned track was considered so strong that it was chosen to lead off the album – though it was McCartney, not Harrison, who handled lead guitar duties on the song.

McCartney also joined Harrison to record the stunning dual-guitar lead work on Lennon's And Your Bird Can Sing.

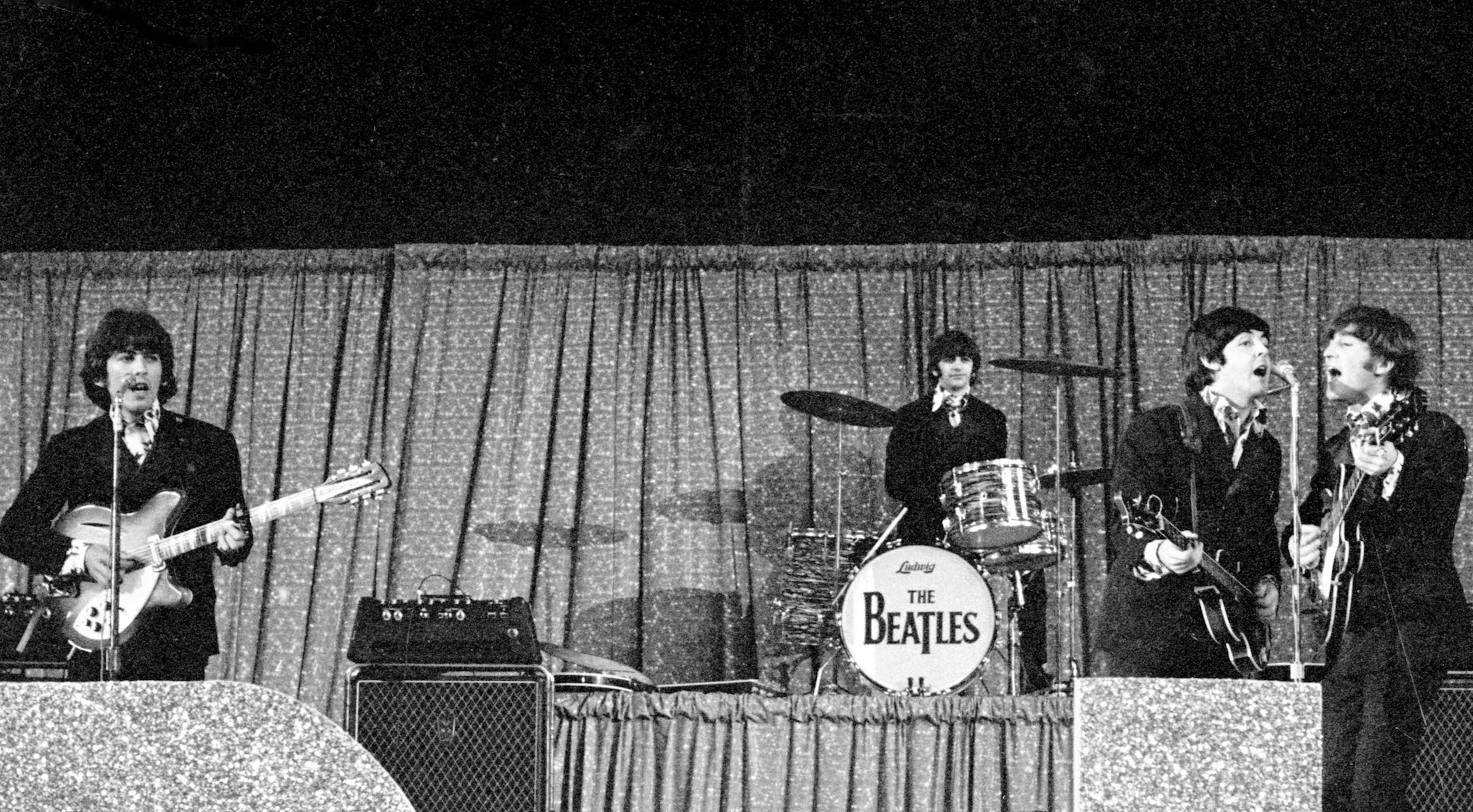

Twin-guitar leads, Leslie-phased vocals, tape loops, strings and horns... It's no wonder that when, upon completing Revolver, the Beatles undertook what would be their final commercial tour – from August 12 to 29, 1966 – the set list featured not a single song from the album. Nearly everything on it would have been impossible for them pull off as a four-piece.

In almost every respect, Revolver represented a departure from the band's teenybopper past and, simultaneously, a signpost to the Beatles' psychedelic future.

It was but a test run for the album that followed: their 1967 milestone, Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of Guitar Player magazine, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.

![The Grateful Dead: Pigpen [left] and Jerry Garcia in action at Santa Clara County Fairgrounds in San Jose, May 18, 1968.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/SiXNMdzjN4PJYWg6TaRqwg.jpg)