Foo Fighters Dave Grohl, Chris Shiflett and Pat Smear Talk New Album, 'Concrete and Gold'

It’s just after nine a.m. in Los Angeles when Guitar World catches up with Dave Grohl, who has already been moving at full speed for hours. “Dude, lemme tell you,” he says with mock exasperation. “My morning starts…at night. Like, it’s already the afternoon for me!”

Grohl’s get-up-and-go attitude likely can be attributed, at least in part, to the fact that he lives in a house crammed full with a wife and three daughters—“I usually wake up around 4:30 or something like that,” he reports, “and I get a good hour, hour-and-a-half to myself before my house explodes into a tornado of activity.”

But it’s also just the 48-year-old’s naturally energized demeanor.

To that end, the Foo Fighters—whose last album, 2014’s Sonic Highways, was a transcontinental endeavor that was paired with an eight-part HBO docuseries—recently finished up work on their ninth full-length, Concrete and Gold, and just returned from a slew of overseas shows where they headlined arenas, stadiums and festivals from Reykjavik to Roskilde.

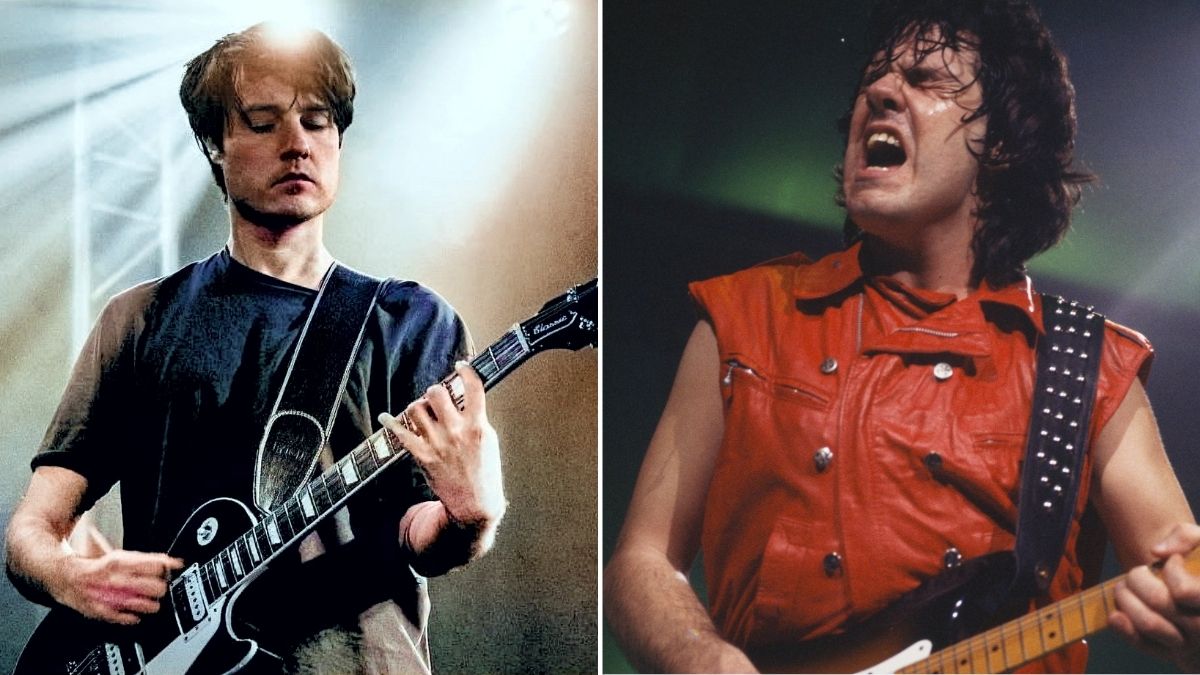

Furthermore, they’re about to embark on a U.S. tour that kicks off in San Bernardino in grand fashion with Cal Jam 17, a 12-hour “rock superfest” that is Grohl’s reimagining of the legendary 1974 festival of the same name.

In place of the original’s lineup of Black Sabbath, Deep Purple and the Eagles, Grohl has put together a bill that includes, among others, Queens of the Stone Age, Cage the Elephant, Royal Blood and, of course, his own band.

After that, the Foo Fighters will continue on, crisscrossing the globe on their own full-scale headlining tour over the course of the next year or two.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Needless to say, this would constitute a pretty full plate of activity for any band—much less one, that, for all intents and purposes, is supposed to be on a break.

“I know, right?” Foo Fighters guitarist Chris Shiflett says about the November 2015 announcement wherein Grohl, in an open letter to fans, opined that he and his bandmates “could use a nice wander through the woods right about now,” hinting at a hiatus that was later confirmed by various members. “Like, what the fuck happened?” Shiflett asks. “I was on vacation.”

He laughs, then continues. “But the truth is, I never really put too much faith in the whole ‘hiatus’ thing, because, you know, in this band it’s usually shorter than is stated.

But we wrapped up touring for the last record, with Dave with his leg broken and everything [in 2015, Grohl fell off a stage during a performance in Gothenburg, Sweden, resulting in his finishing the tour with his leg in a cast, and singing and playing while seated in a self-designed throne], and it was a little before Thanksgiving 2015. And at that time Dave was talking about wanting to take two years off. That was sort of the stated goal. “Which,” he points out, “I never really believed…”

As it turns out, Shiflett had good reason to doubt Grohl’s intentions. According to Pat Smear, the former Germs and Nirvana guitarist who comprises the final third of the Foos' three-ax attack, “The last time we were going on a long break, Dave started making [the 2013 documentary film] Sound City. And we were like, ‘What about us, man? We wanna do it too!” So we ended up making that album [Sound City: Real to Reel] and touring for that. That’s how Foo Fighters breaks go.”

That said, the band members, who also include bassist Nate Mendel, drummer Taylor Hawkins and keyboardist Rami Jaffee, did get a bit of time off. They spent the holidays and early part of 2016 at home, and Hawkins and Shiflett even managed to squeeze out solo albums (KOTA and West Coast Town, respectively). But soon enough, Grohl came calling. “The beginning of the summer of 2016 was the first sort of text from Dave implying things were gonna pick back up soon,” Shiflett recalls.

In Grohl’s defense, initially he didn’t know how soon “soon” would be.

“At the end of the last tour [for Sonic Highways] everyone was completely exhausted—mentally, physically, emotionally,” he explains.

“We were like a rag that got squeezed dry. It was time to stop, and we knew it. We finished the tour, I still wasn’t walking 100 percent yet after breaking my leg, we had recorded the Saint Cecilia EP just as kind of a thank-you to the fans…and then we got home. And it’s weird when you come home from that much touring and that much traveling and that much performing. You’re dropped silent onto your back porch with this big question mark, like, ‘Okay, who am I? What am I doing here?’ It’s strange. It can turn into that Apocalypse Now scene with the mirror and the bloody hand if you’re not careful, you know?”

Indeed, Grohl soon began to get restless. “About once a month I would walk up into my home studio and look at the guitar and look at the drum set and then turn off the lights and walk out,” he recounts.

“And then a month later I’d look at the guitar, look at the drum set, maybe sit down in front of the drums for 15 minutes, and then turn out the light and walk out. A month after that, I’d started setting up microphones. Six months went by, and I just hit this vein where riffs and melodies started coming out. So I would record demos by myself and then send them to the guys and say, ‘Hey, what do you think? Is this cool?’ And after maybe 15 or 16 of them I realized that, if we wanted to, we could walk into the studio and make the record.”

Initially, the band reconvened at keyboardist Jaffee’s studio to work on music, but it wasn’t until they paired up with producer Greg Kurstin and entered East-West Studios in Hollywood that Concrete and Gold really took shape. The Foos have worked with a variety of producers over the years, including Gil Norton (Pixies, Echo and the Bunnymen) and Butch Vig, whose relationship with Grohl extends back to Nirvana’s Nevermind.

But they’ve never worked with someone like Kurstin, a songwriter and multi-instrumentalist who, in addition to forming one half of the indiepop duo The Bird and the Bee, has crafted studio productions for the likes of Adele and Sia, among others.

It was an unlikely pairing, to be sure—a fact that wasn’t lost on Grohl’s bandmates. “One day, Dave said, ‘Hey, I invited Greg down to come see what we do,’ ” Smear recalls. As for whether Smear was familiar with Kurstin’s résumé? “Yeah, Dave probably mentioned it before he came down,” he says, then laughs. “Which was confusing.”

But, Smear continues, “then Greg came to the studio and I realized, Oh, you’re like us! You were some punk rock kid who played in weirdo bands, and somewhere along the line you happened to do that thing that now everyone knows you for. So Greg may have veered off into other directions like jazz and pop and stuff, but I got it. And we immediately got along.”

For Grohl, there was intentionality in pursuing Kurstin, who has a particular talent for crafting lush—and often left-of-center—harmonies, melodies and instrumental arrangements. “I think we all knew from the way Dave was talking even in the early stages that, sonically, musically, he wanted to do something different this time,” Shiflett says.

“I don’t know if it was super clear what that ultimately was going to mean, but certainly a very big part of that would be his decision to bring in Greg Kurstin. Because we had a guy in the studio producing us who brought something very different from what is normally a Foo Fighters record. And I think that, through Greg, Dave was able to realize things…there are things on this record that Dave has talked about wanting to do for a long time. We just never did ’em. But Greg was able to facilitate some of that stuff.”

Explains Grohl, “Greg and I, we’d hung out for years, but I didn’t imagine that he would ever make a Foo Fighters record. At the same time, I always imagined, what if he did? I knew that he would be able to stretch us in those directions—melodically and sonically, and also in terms of production and composition—farther than we’ve ever gone. Because he’s a fucking genius. And I do not say that lightly. I’ve met a lot of brilliant musicians, and Greg Kurstin, without a doubt, is the most brilliant musician I’ve ever met in my entire life. And I knew that we were about to make an album that was gonna push out in a direction we’ve always wanted to go, but never fully explored.”

The result is an album that, at its core, at least, still sounds like a Foo Fighters album, chock full of explosive, smack-you-in-the-face riffs, whisper-to-a-scream dynamic shifts, massive, stadium-shaking choruses and insanely catchy hooks and melodies. From the shapeshifting first single, “Run,” to the lurching, punkish “La Dee Da,” the anthemic “The Line” (Shiflett: “that’s the sound that made me fall in love with this band”) to the Beatles-esque acoustic fingerpicker “Happy Ever After (Zero Hour),” Concrete and Gold boasts some of the Foos' strongest work together.

But there is also a depth of sound and instrumentation previously unheard from the band. Whether it’s the bloated distorto-bass that powers “La Dee Da,” the swirling miasma of background vocals that lifts the chorus of the otherwise cock-rocking “Make It Right,” or the lush, practically monolithic wall of sound that fortifies the title track (“the heaviest and most beautiful thing we’ve ever written,” says Grohl), virtually every song on Concrete and Gold offers up a twist on the characteristic Foo Fighters sound, and often in a way that requires repeated listens to fully absorb.

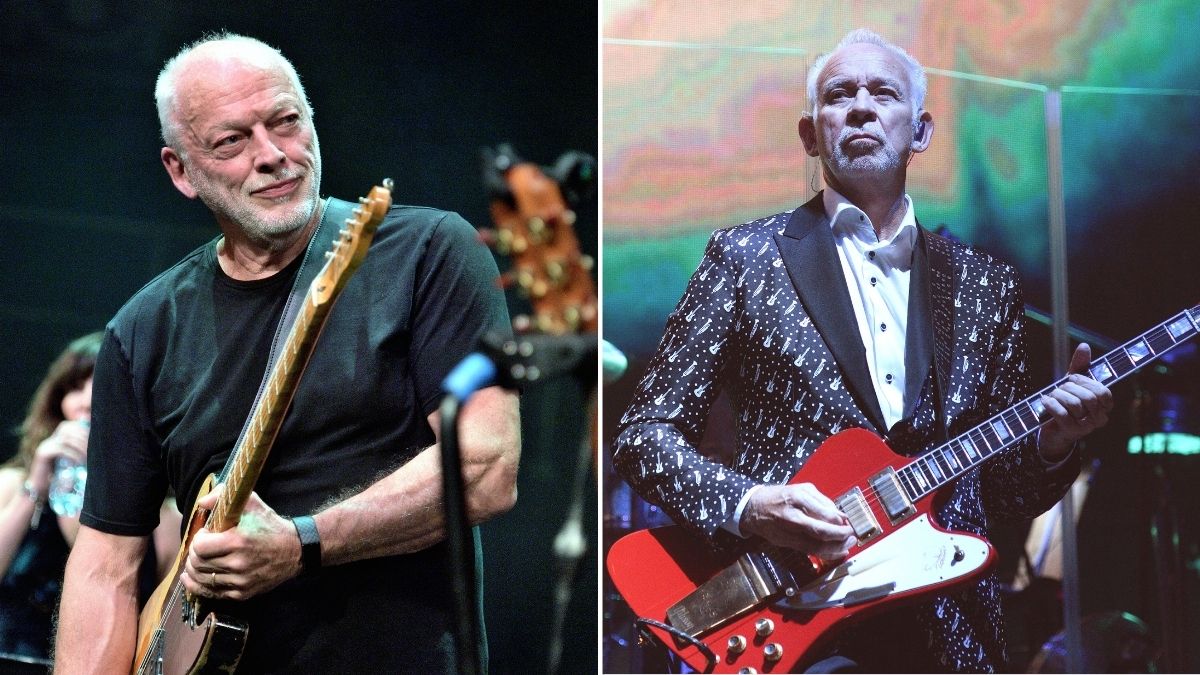

Grohl with his custom Gibson Trini Lopez guitar, also known as the DG-335 (photo: Jen Rosenstein)

“A lot of the harmony stuff, the countermelodies, a lot of that was Greg and Dave working that out. And Taylor, too,” Shiflett says. “And Greg was really instrumental in things like the orchestrated layers of vocals. We’ve never had, like, three- and four-part harmonies on our records before. So he definitely brought something new.”

Perhaps the finest example of the sonic fruits of the collaboration between Kurstin and the band is a song called “The Sky Is a Neighborhood,” arguably Concrete and Gold’s centerpiece. Built on a spare, almost bluesy framework, the track is centered around Grohl’s anguished vocal, which is then fortified with all manner of instrumental ear candy to create a kaleidoscopic sonic picture. Says Shiflett, “There’s super-arranged strings, keyboards, all these harmonies and different guitar things going on.” Adds Grohl, “There’s no way we would’ve done that song without Greg.”

Interestingly, for all its production, “The Sky Is a Neighborhood,” Grohl says, actually came together pretty quickly, and somewhat at the last minute. “It was the last song we recorded. We had finished the record and we had two weeks off before we were supposed to mix. I went down to Hawaii, and I came back and I said to everybody, ‘I think I’ve got one more in me.’ Because I always feel like I have one more in me. You know, ‘Everlong’ was that one more song. ‘The Pretender’ was that one more song. So I wrote that song and I came back and we recorded it really quickly. And, I mean, the bare bones of the song are really simple. Taylor and I recorded the drums and guitar live in maybe two takes. And then we just started piling stuff onto it.”

“It was sort of a free-for-all because it was so fast,” Smear adds. “Like, ‘Come up with something, we’re recording. Go do it!’ ”

Grohl continues, “After listening to it, I said to Greg, ‘I feel like this bridge could have some sort of string section.’ And Greg said, ‘Okay, give me 15 minutes. I’ll write something up.’ And so I walked out of the room. I came back and he goes, ‘Check this out…’ He hit play, and he had done a keyboard string section demo. And I laughed so fucking hard because it was what I’ve always wanted to do. It was perfect.”

In addition to stepping outside of their comfort zone with Kurstin, the band also changed things up when it came to gear.

“The way Greg records, we knew there was this opportunity to branch out and get some different sounds,” Grohl says. “So one of the ideas before we even went in to make the record was that we’d use equipment that we don’t normally use. There were a few times where I used my number one [Gibson] Trini [Lopez] and Fender Tone-Master amps, but typically for the more jangly stuff we would lean toward a vintage Gibson or Tele. And we were literally grabbing old P.A. systems and keyboard amps and things that were just on the verge of exploding and piling them up. We were throwing stuff together to try to find the coolest sounds we could.”

“Dave said, ‘Just don’t bring your normal gear. Bring something different,’ ” Shiflett recalls.

“So everybody showed up with their wacky stuff that they don’t normally play. And that was kind of the spirit of the record. For me, I normally do a lot of Les Paul through a Friedman. I don’t think I played that at all. It was all guitars with P-90s, little combo amps, shit like that. I got a hand-wired Vox AC15 right when we were doing the demos, and that was kind of the magic amp for me throughout this thing. I had my little Fifties tweed [Fender] Champ. I had a bitchin’ tweed Vibrolux, and I’m sure there was a Deluxe Reverb, maybe a Super Reverb. Then I have a ’68 non-reverse [Gibson] Firebird that I played probably on most of the record. That was kind of my go-to guitar. I also played my signature [Fender Tele Deluxe] model when I needed something with a little more crunch, and I had a couple Teles and a 12-string Rickenbacker that I put on some stuff as well.”

Adds Smear, “I brought in some Les Pauls and other big, cumbersome weird guitars. And I fell in love. Like, ‘I get it! These are great guitars!’ And then for my amp I was using this weird combo that Dave’s guitar tech came up with, which was basically an old Seventies vocal mixing board that you might have in your rehearsal place, and that we ran into an old transistor bass head. And that became my sound for most of the record, along with some other things, like an Orange, which I had never used before.”

Effects-wise, Shiflett says that “There’s a lot of warbly things like phasers and flangers, an [Electro-Harmonix] Memory Man, that kind of stuff. And there’s some fuzz—I think I used that Jack White pedal, the Bumble Buzz, and there’s a [JHS Pedals] Muffuletta on ‘The Sky Is a Neighborhood.’ ” Smear also reports that Kurstin often took the reins when it came to manipulating guitar sounds. “Greg loves effects,” he says. “And sometimes while you were tracking he’d be playing an effect. Just turning knobs and things.” Smear laughs. “And I’m watching him like, ‘Oh, he’s playing, too!’ ”

Outside of Kurstin and the band members, Concrete and Gold also features a slew of guest musicians, from Boyz II Men’s Shawn Stockman, who, after meeting Grohl in the EastWest parking lot, laid down a ridiculously massive stack of backing vocals on the chorus of the title track, to Kills frontwoman Alison Mosshart to jazz saxophonist Dave Koz. Pop icon Justin Timberlake makes an appearance as well, though even his star power is eclipsed by another guest, Paul McCartney, who contributed, of all things, a rock-solid drum track to the Taylor Hawkins–sung “Sunday Rain.”

“I think it was Dave’s idea to have him play drums,” Shiflett says of McCartney. “And he’s solid. You know, it’s a very different approach to Taylor or Dave. Those guys are very modern, and Paul’s got that old school thing, where he’s not killing the drums. It’s a very different, loosey-goosey kind of feel. And the coolest thing about it was that afterward he just wanted to hang out. It turned into an hour of just kind of noodling around with Paul McCartney. Which blew my mind.”

“He’s exactly how you’d hope he’d be,” Smear adds of McCartney. “He just loves music and loves to play. He came in, never even heard the song before, didn’t know it at all. He did, like, two takes. And then we just jammed. So that was a good day.”

Overall, Grohl says, “With this record, we just had time. We had space.” Due to the fact that the general public believed the Foo Fighters to be on a hiatus, he continues, “We didn’t tell anybody that we were even making a record. So we had no deadline, you know? We had no pressure. And because of that there was a lot more freedom to try different things.” At this point, of course, that has all changed. “Once we go in and we make the record, it’s like starting up a fucking steamroller,” Grohl says. “Once it starts, it doesn’t stop.”

And it all started pretty quickly once the sessions for Concrete and Gold wrapped. Following the recording, the band almost immediately began rolling out new songs onstage. Says Smear with a laugh, “We actually started rehearsing for the tour, and all we did was play the new songs. And on like the second-to-last day someone said, ‘Hey, we should probably go over the old songs, too!’ ”

As for whether they believe there’s been a big change in sound and feel from those old songs to the new ones?

“I wouldn’t say [the shift] is, like, gigantic,” Shiflett says. “It’s more like a natural progression. And probably a lot of that is just, like, as the years go by, everybody gets more comfortable doing their thing. I also know Dave always likes to change it up and keep things moving and do things a little different from record to record. It doesn’t hurt to have that spirit in there.”

“At the very least, I know that we couldn’t have made this record 20 years ago,” Grohl says.

“There’s a freedom in this band now that feels like a weight lifted off our backs, because we know exactly who we are. I remember when we came back from this last break and did our first show, at the BottleRock Festival [in Napa Valley, California], everybody was a little nervous because we weren’t in the mindset of going out and bringing the party to 40,000 people. Right before we went out, we were standing on the side of the stage with our instruments strapped on. And I looked at everybody and I was like, “Hey!” They looked at me and I said, ‘We’re the Foo Fighters, goddammit!’ And then we just laughed. Because you know, to us, we know exactly what that means.”

Grohl continues. “So I just feel like there’s a bit more of a relaxed confidence that comes with age. I mean, I never thought that I’d be doing this past 30 years old. And that was a long fucking time ago! But when I walk backstage now and see the fresh faces of all the new bands, and I’m the guy with fucking grey hair in my beard, I feel kinda proud. Proud that we’re still here. And I also don’t think that we could have made an album like Concrete and Gold without a little bit of grey hair thrown in there, you know what I mean? Because each album is like a rung on a ladder. And you just keep climbing.”

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.