Excerpt from Brad Tolinski's 'Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page': Recording 'Led Zeppelin'

Brad Tolinski, editorial director of Guitar World, Revolver and Guitar Aficionado magazines, has interviewed Jimmy Page more than any other journalist in the world.

Those interviews have led to his new book, Light & Shade: Conversations With Jimmy Page, which was published today, October 23, by Crown Publishing.

Light & Shade is drawn from the best of more than 50 hours worth of conversations that touch on everything from the music scene of the '60s; Page's early years as England's top session guitarist working with The Who, The Kinks and Eric Clapton; his time with The Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin and his post-Zep projects. The book provides readers with the most complete picture of the media-shy guitarist ever published.

Below is an excerpt from the book, where Page discusses the work that went into recording Led Zeppelin's self-titled 1969 debut album. For another excerpt that focuses on Page's time in The Yardbirds, check out the December 2012 issue of Guitar World. It's available on newsstands now and at the Guitar World Online Store.

[[ Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page is available now at the Guitar World Online Store, plus Amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, book stores and other retailers. ]]

“I WANTED ARTISTIC CONTROL IN A VISE GRIP…”

Page leaves the Yardbirds, forms Led Zeppelin and records their first two albums.

BRAD TOLINSKI: Right from the beginning, you were able to translate the extreme dynamism of Led Zeppelin’s live act into a dynamic studio recording: What was your secret?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

JIMMY PAGE: That is interesting, isn’t it? One usually thinks of a dynamic album being translated into a dynamic live performance, but in the early days, it was the other way around for us.

I think part of the key was that we miked John Bonham’s drums like a proper acoustic instrument in a good acoustic environment. The drums had to sound good because they were going to be the backbone of the band. So I worked hard on microphone placement. But then again, you see, when you have someone who is as powerful as John Bonham going for you, the battle is all but won.

So the way to capture a dynamic performance is, essentially, to capture the natural sound of the instruments.

PAGE: Sure. You shouldn’t really have to use EQ in the studio if the instruments sound good. It should all be done with microphones and microphone placement. The instruments that bleed into each other are what creates the ambience. Once you start cleaning everything up, you lose it. You lose that sort of halo that bleeding creates. Then if you eliminate the halo, you have to go back and put in some artificial reverb, which is never as good.

That’s particularly true of the blues. Playing the blues is not a cerebral experience. Its often said that musicians try to summon the spirit of the blues when they play. But how can that be done when there is no room, no space? And space is also essential if If you want to capture the mojo created by musicians playing together, live.

PAGE: And that’s probably the biggest difference between the music made in the Fifties and music made from the Seventies on—everything suddenly had to be cleaned up. You do that and you take that whole punch out of the track.

Along with that strong musical vision you had in those early days, you also took a unique approach to handling the business aspect of the band. By producing the first album and tour yourself, was it your intention to keep record company interference to a minimum and maximize the band’s artistic control?

PAGE: That’s true. I wanted artistic control in a vise grip, because I knew exactly what I wanted to do with the band. In fact, I financed and completely recorded the first album before going to Atlantic. It wasn’t your typical story where you get an advance to make an album—we arrived at Atlantic with tapes in hand. The other advantage to having such a clear vision of what I wanted the band to be was that it kept recording costs to a minimum. We recorded the whole first album in a matter of 30 hours. That’s the truth. I know, because I paid the bill. [laughs] But it wasn’t all that difficult because we were well rehearsed, having just finished a tour of Scandinavia, and I knew exactly what I wanted to do in every respect. I knew where all the guitars were going to go and how it was going to sound—everything.

The stereo mixes on the first two albums were very innovative. Was this planned before you entered the studio, as well?

PAGE: I wouldn’t go that far. Certainly, though, after the overdubs were completed I had an idea of the stereo picture and where the echo returns would be. For example, on “How Many More Times,” you’ll notice there are instances where the guitar is on one side and the echo return is on the other. Those things were my ideas. I would say the only real problem we had with the first album was leakage from the vocals. Robert’s voice was extremely powerful and, as a result, would get on some of the other tracks. But oddly, the leakage sounds intentional. I was very good at salvaging things that went wrong.

For example, the rhythm track in the beginning of “Celebration Day” [from Led Zeppelin III was completely wiped by an engineer. I forget what we were recording, but I was listening through the headphones and nothing was coming through. I started yelling, “What the hell is going on?” Then I noticed that the red recording light was on what used to be the drums. The engineer had accidentally recorded over Bonzo! And that is why you have that synthesizer drone from the end of “Friends” going into “Celebration Day,” until the rhythm track catches up. We put that on to compensate for the missing drum track. That’s called “salvaging.”

The idea of having a grand vision and sticking to it is more characteristic of the fine arts than of rock music. Did your having attended art school influence your thinking?

PAGE: No doubt about it. One thing I discovered was that most of the abstract painters that I admired were also very good technical draftsman. Each had spent long periods of time being an apprentice and learning the fundamentals of classical composition and painting before they went off to do their own thing.

This made an impact on me because I could see I was running on a parallel path with my music. Playing in my early bands, working as a studio musician, producing and going to art school was, in retrospect, my apprenticeship. I was learning and creating a solid foundation of ideas, but I wasn’t really playing music. Then I joined the Yardbirds, and suddenly—bang!—all that I had learned began to fall into place, and I was off and ready to do something interesting. I had a voracious appetite for this new feeling of confidence.

You’ve often described your music in terms of “light and shade,” which are definitions used in painting and photography rather than rock music.

PAGE: “Structure,” as well; architecture plays a part, too.

“Good Times Bad Times” kicks off Led Zeppelin. What do you remember about recording that particular track?

PAGE: The most stunning thing about that track, of course, is Bonzo’s amazing kick drum. It’s superhuman when you realize he was not playing with a double kick. That’s one kick drum! That’s when people started understanding what he was all about.

What did you use to overdrive the Leslie [a rotating speaker used primarily for organs] on the solo?

PAGE: [thinks hard] You know…I don’t remember what I used on “Good Times Bad Times.” But curiously, I do remember using the board to overdrive a Leslie cabinet for the main riff in “How Many More Times.” It doesn’t sound like a Leslie because I wasn’t employing the rotating speakers. Surprisingly, that sound has real weight. The guitar is going through the board, then through an amp that was driving the Leslie cabinet. It was a very successful experiment.

How did you develop the backward echo at the end of “You Shook Me”?

PAGE: When I was still in the Yardbirds, our producer, Mickie Most, would always try to get us to record all these horrible songs. During one session, we recorded “Ten Little Indians,” an extremely silly song that featured a truly awful brass arrangement. In fact, the whole track sounded terrible. In a desperate attempt to salvage it, I hit upon an idea. I said, “Look, turn the tape over and employ the echo for the brass on a spare track. Then turn it back over and we’ll get the echo preceding the signal.” The result was very interesting—it made the track sound like it was going backward.

Later, when we recorded “You Shook Me,” I told the engineer, Glyn Johns, that I wanted to use backward echo on the end. He said, “Jimmy, it can’t be done.” I said, “Yes, it can. I’ve already done it.” Then he began arguing, so I said, “Look, I’m the producer. I’m going to tell you what to do, and just do it.” So, he grudgingly did everything I told him to, and when we were finished he started refusing to push the fader up so we could hear the result. Finally, I had to scream, “Push the bloody fader up!” And, lo and behold, the effect worked perfectly. When Glyn heard the result, he looked bloody ill. He just couldn’t accept that someone knew something that he didn’t—especially a musician.

The funny thing is Glyn did the next Stones album, and what was on it? Backward echo! And I’m sure he took full credit for the effect.

When people talk about early Zeppelin, they tend to focus on the band’s heavier aspects. But your secret weapon was your ability to write great hooks. “Good Times Bad Times” has a classic pop hook. Did playing sessions in your pre-Yardbirds days hone your ability to write memorable parts?

PAGE: I would say so. I learned things even on my worst sessions—and believe me, I played on some horrendous things.

Did your friends ever tease you for playing jingles?

PAGE: I never told them what I was doing. I’ve got a lot of skeletons in my closet, I’ll tell ya!

How did “How Many More Times” evolve?

PAGE: That has the kitchen sink on it, doesn’t it? It was made up of little pieces I developed when I was with the Yardbirds, as were other numbers such as “Dazed and Confused.” It was played live in the studio with cues and nods.

John Bonham received songwriting credit for “How Many More Times.” What was his role?

PAGE: I initiated most of the changes and riffs, but if something was derived from the blues, I tried to split the credit between band members. [Robert Plant did not receive any songwriting credits on Led Zeppelin, as he was still under contract to CBS.] And that was fair, especially if any of the fellows had input on the arrangement.

You also used a violin bow on the stings of your guitar on that track.

PAGE: Yes, like I said, we used the kitchen sink. I think I did some good things with the bow on that track, but I really got much better with it later on. For example, I think there is some really serious bow playing on the live album [The Song Remains the Same]. I think some of the melodic lines are pretty incredible. I remember being really surprised with it when I heard it played back. I thought, Boy, that really was an innovation that meant something.

How did you come up with the idea of using a violin bow on an electric guitar?

PAGE: When I was a session musician, I would often play with string sections. For the most part, the string players would keep to themselves, except for a guy who one day asked me if I ever thought of playing my guitar with a bow. I said I didn’t think it would work because the bridge of the guitar isn’t arched like it is on a violin or cello. But he insisted that I give it a try, and he gave me his bow. And whatever squeaks I made sort of intrigued me. I didn’t really start developing the technique for quite some time later, but he was the guy that turned me onto the idea.

Your bow playing, especially on “Dazed and Confused,” is really enhanced by echo.

PAGE: It was actually reverb. We used those old EMT plate reverbs.

That’s a little surprising, because there are areas that sound like you’re using tape echo. In fact, Led Zeppelin was the first album that I can think of that employed such long echoes and delays.

PAGE; It’s a little difficult to remember, and I can’t tell you on exactly which tracks, but there was a lot of EMT plate reverb put on to tape and then delayed—machine delayed. You were only given so much time on those old spring reverbs.

Another interesting aspect of the first album is your use of the acoustic guitar, which was something that separated you from other guitar heroes of the day like Clapton or Hendrix.

PAGE: Our acoustic songs were designed to create dynamics both on the albums and in live performance. The harder songs wouldn’t have had as much impact without the softer ones. It was funny to us that everyone made such a big deal out of the fact that we used acoustic instruments on Led Zeppelin III, because they were there from the beginning.

The first album featured two folk-oriented songs, “Babe I’m Gonna Leave You” and “Black Mountain Side,” but the critics just never noticed. It makes you wonder. I think they just got completely absorbed in the second album, which was more high energy. But even the second album had its quiet moments in “Ramble On” and “Thank You.”

Our performance of “Babe I’m Gonna Leave” showed how original the band was. There weren’t many hard rock groups who would have the nerve to play a song originally recorded by [folk singer] Joan Baez!

Your arrangement of the traditional British folk song, “Black Mountain Side” was also an interesting choice. It was a tune recorded by revivalists like Anne Briggs and Bert Jansch, but you saw the potential as a rock song.

PAGE: As a musician, I’m only the product of my influences. The fact that I was listening to folk, classical and Indian music in addition to rock and blues was one thing that set me apart from so many other guitarists at the time.

How did the Indian and Middle Eastern elements heard on songs like “Black Mountain Side,” “White Summer, “Friends” and “Kashmir” take form?

PAGE: Eastern music was always appealed to me. I went to India after I came back from a tour with the Yardbirds in the late Sixties, just so I could hear the music firsthand.

Let’s put it this way—I had a sitar before George Harrison got his. I wouldn’t say I played it as well as he did, though; I think George used it well. The Beatles’ “Within You, Without You” is extremely tasteful. He spent a lot of time studying with [Indian musician] Ravi Shankar, and it showed. But I can remember going to see Ravi in concert very early on. To show you how far back it was, there were no young people in the audience at all, just a lot of older people from the Indian embassy. This girl I knew was a friend of his, and she took me to see him. She introduced us after the concert, and I explained that I had a sitar but I didn’t know how to tune it. He was very nice to me and wrote down the tuning on a piece of paper.

But it’s really hard for me to say exactly where I got my technique, because it’s a combination of a lot of things that were floating around. Sometimes I tell people it’s a product of my “C.I.A. connection”—which is shorthand for Celtic, Indian and Arabic music.

You recorded “Baby Come On Home” during the Led Zeppelin I sessions, but it didn’t see the light of day until 1993’s Boxed Set 2.

PAGE: I don’t think we finished it—the backing vocals weren’t very clever. And, at the time, we thought everything else was better. Simple as that really. But don’t get me wrong, the track is good and Plant’s singing is excellent. It’s just that we set such high standards for ourselves.

How did Atlantic react when you presented them with the first album?

PAGE; They were very keen to get me. I had already worked with one of their producers and visited their offices in America back in 1964, when I met [Atlantic executives] Jerry Wexler and Leiber and Stoller and so on. They were aware of my work with the Yardbirds because they were pretty hip people, so they were very interested. And I made it very clear to them that I wanted to be on Atlantic rather than their rock label, Atco, which had bands like Sonny and Cher and Cream. I didn’t want to be lumped in with those people—I wanted to be associated with something more classic. But to get back to your question: Atlantic’s reaction was very positive—I mean they signed us, didn’t they? And by the time they got the second album, they were ecstatic.

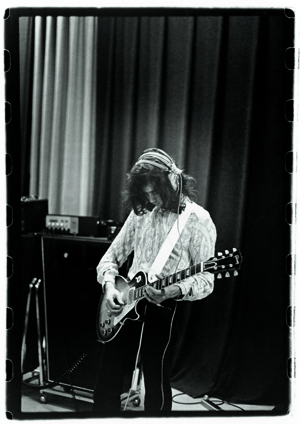

I was looking at some old photos of the band recently, and I noticed you were using an assortment of fairly bizarre amplifiers and guitars around the time of the first album. What were you using before you switched to the Marshall Super Lead/Les Paul combination that most people associate you with?

PAGE: It was basically whatever we could afford at that time. I didn’t really make any money when I was with the Yardbirds, so I was pretty broke in the beginning. I actually had to finance the first Zeppelin album with money I had saved as a session musician. What I had as equipment was very minimal. I had my Telecaster that Jeff Beck gave me, a Harmony acoustic, a bunch of Rickenbacker TransSonic cabinets left over from the Yardbirds, and a hodge-podge of amps—Vox and Hiwatts, mostly.

I also had a black Les Paul Custom with a tremolo arm that was stolen during the first 18 months of Zeppelin. It was lifted at the airport. We were on our way to Canada and, somewhere, there was a flight change and it disappeared. It never arrived at the other end.

What are you playing on the first album?

PAGE: Primarily the Telecaster.

That Tele sported quite a spectacular psychedelic custom paint job.

PAGE: I painted it myself. Everyone painted guitars back then.

[[ Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page is available now at the Guitar World Online Store, plus Amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, book stores and other retailers. ]]

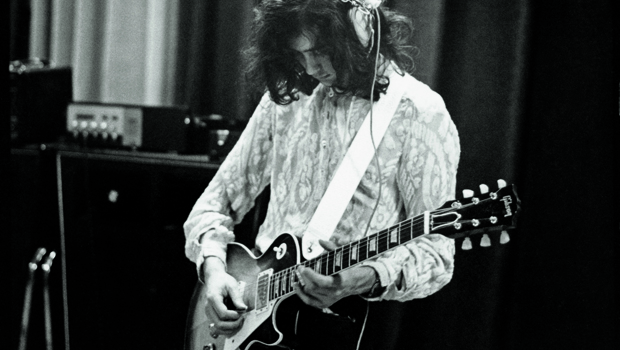

Photo: Chuck Boyd

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away Brad was the editor of Guitar World from 1990 to 2015. Since his departure he has authored Eruption: Conversations with Eddie Van Halen, Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page and Play it Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound & Revolution of the Electric Guitar, which was the inspiration for the Play It Loud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 2019.