Eric Clapton Talks Gear, Robert Johnson and New Album, 'I Still Do'

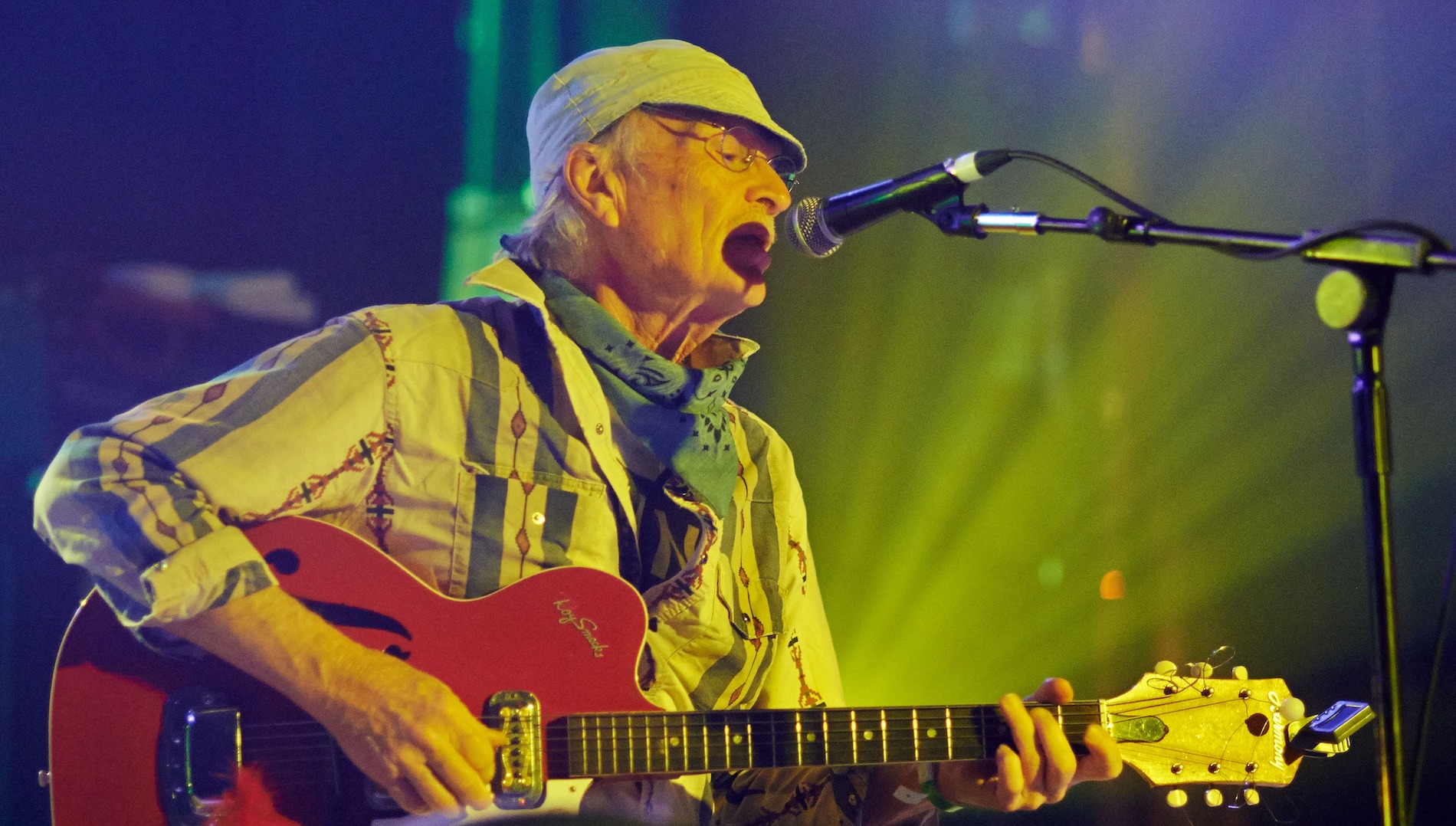

When last we heard from Eric Clapton, he was dropping hints about retiring, alluding to a time in the not-too-distant future when he might claim his gold watch and lay down his guitar for good.

Now, nearly two years later, the 71-year-old guitar legend has released a studio album with a promising, first-person title: I Still Do.

Is it a reassuring note to fans, something along the lines of “Calm down, gang—I’m still here”?

Given the exuberance with which Clapton speaks about the record, not to mention its strong performances, punchy mix and intriguing material, including his first-ever studio recording of Robert Johnson’s eerie “Stones in My Passway” and two “new” JJ Cale compositions, we’re gonna take that as a yes.

Like his last two studio releases, 2013’s Old Sock and 2014’s The Breeze: An Appreciation of JJ Cale, I Still Do finds Clapton in a reflective mood, looking back at the artists and songs that inspired him as a young man, connecting with old friends—including producer Glyn Johns—and honoring sepia-toned family memories. And it all starts with the title.

“I Still Do is a tribute, a quote from my aunt, who passed away the year before last,” Clapton tells us. “When I went to see her, I said, ‘I want to thank you for being who you were and looking after me when I was a little boy—and a difficult little boy.’ She said, ‘Well, I liked you and I still do.’ I thought, That's it.”

I Still Do also finds Clapton getting a bit cheeky with his liner notes. When the album was initially announced in February, fans were quick to notice that one “Angelo Mysterioso” was credited with vocals and guitar on “I Will Be There.” Noting the name’s similarity to “L’Angelo Misterioso,” the pseudonym George Harrison famously used when he co-wrote and played guitar on Cream’s “Badge” in 1969, the media rode with it, announcing that Harrison—who died in 2001—somehow appeared on I Still Do. Clapton’s camp added to the mystery when they posted a Facebook item denying that Harrison was involved—and then quickly pulled the post.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Let’s just say one of the things Clapton can still do is keep a secret.

You haven’t worked with Glyn Johns since your two late-Seventies studio albums, Slowhand and Backless. What brings him back into the fold?

I had just read his autobiography [2014’s Sound Man: A Life Recording Hits with The Rolling Stones, The Who, Led Zeppelin, The Eagles, Eric Clapton, The Faces…], where he had mentioned me and said he hoped we were still friends. And I thought, I should give him a call. So we met up in 2014. We were just having dinner, reminiscing, since I hadn’t seen him in a very long time. And then he suggested we find some time to play together again—and that was that. It was just a conversation, and I think we both checked a little bit later to see if it was genuine. Bit by bit, it became more and more of a serious endeavor. And then in October of last year we went into the studio and started working without really having too much of a road map.

Here’s a three-part Glyn Johns question: What is he like to work with? What does he bring to a project? Has he changed much since the late Seventies?

Not essentially, no. He's calmed down a bit. He’s very forthright. He doesn't waste time or words getting to the point. If he thinks you're on to something, he's very enthusiastic and encouraging. If he thinks you're going in the wrong direction, he'll try and shut it down. He's good to work with in that respect. And I like people who are direct, people who know what they’re listening to. He has a musical background, he’s a musician and had a small career a long time ago, so he knows what he's talking about. Ultimately for me, he's one of the best guys I've ever seen on the board. He can get very quickly to the right sound, the right balance, if you have quite a few instruments. He can mix that really quickly and get it sounding good.

Speaking of names from the past, I Still Do features drummer Henry Spinetti and keyboardist Chris Stainton, guys whose names started appearing in your liner notes more than 30 years ago. Your last album, [2014’s] The Breeze: An Appreciation of JJ Cale, featured drummer Jamie Oldaker and guitarist Albert Lee, two more former Eric Clapton band members from decades past. What is it about working with old friends that you enjoy most? Is it just fun to look backward sometimes?

I think it’s the familiarity of walking in a path that they know. A well-worn relationship is stable, reassuring. There's a lot left unsaid that way. I think starting up with someone fresh, I'd have to be sure we were on the same page, and sometimes it's difficult to get a really direct reading on that. These guys are experienced, and we've been there before. The guys that played on this last album, I can just walk in the room. We don't rehearse; it's almost unnecessary to do anything. We can just play an evening of songs without really having any direction. That's just having a history together.

Which brings me to a mysterious credit on the new album. “Angelo Mysterioso” sings and plays acoustic guitar on “I Will Be There.” The pseudonym is very similar to the name George Harrison used on Cream’s “Badge.” There was some speculation that you’d found an unfinished song featuring Harrison; however, I've heard the new album three times now, and I know that's not George. Who is it?

No, It's not George. Well, the thing is, the person wishes to remain anonymous. So we came to that arrangement, and we both thought it was the best idea, for one reason or another. And I can't even tell you that much. I’m sworn to secrecy, and I hope he is too. But I quite liked it. I heard there were rumors about it being George, and I thought that was great because it's nice that people know about that story. That's what we used to do a lot, and I still like to do that now. I've been that “angel” sometimes. George was, and now there's someone else. So I can't say who it is, but I like the speculation.

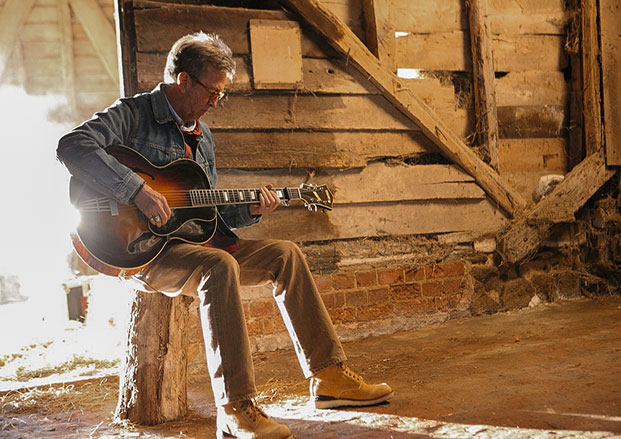

If you can’t name guitarists, let’s discuss guitars. What gear did you use on the album? Anything new?

Well, there's always something new. New stuff comes in from [amp builder] Alexander Dumble. We have a dialogue now, which is stronger than it's ever been. He tells me what he's up to and he's helped me out with a few things. I've given him amps to restore, so I used a restored Fender Vibrolux that he looked at and did a little modification on.

Also a Fender Bandmaster, which is kind of my constant amp right now. It's an interesting amp because it's quite big sounding, but you could use it moderately at the same time, so it's very adaptable. And if I want to go down in size, the Vibrolux is the one I’ll use. The guitars on the album were a Strat with modifications—my signature guitar that's got a compressor in it. Plus a 1960 ES-335. It's a beautiful, very rich-sounding guitar. I used that when I was playing slide because it can sustain really well. I used a Les Paul as well, but mainly those were the two electrics. And I used a couple of different Martins.

The new album is pretty diverse, but my favorite of the bunch is your version of JJ Cale’s “Somebody's Knocking.” I know you’ve played it live in the past, but Cale never officially recorded it. How did you come across it?

It's an interesting story. When I went to his funeral [Cale died July 26, 2013], I met with Christine, his wife, and we talked about what was left, in terms of songs. I asked her, you know, maybe prematurely. But I was very curious to know if there was a legacy. And she said, "Oh, there's some stuff. I'll make you some CDs.”

She gave me two CDs a couple of days later with about 20 songs on each, so I had those locked up in a safe. [laughs] They’re so precious to me. They're unreleased JJ demos, and some of them are really, really out there; others are the kind of thing you'd expect from JJ, but that's one of the songs, “Somebody's Knocking.” His version is totally different; it's very quiet and subtle. We tried to do it that way, but I can't get the energy, so we started doing it more like Albert King, or like a blues/R&B thing—really old school. That gives it the character, I think. We play that as an opening song a lot when I'm on stage, because it's just easy, which is the whole thing about JJ's legacy.

Your Strat tone really stands out on that track. It’s unique from the rest of the album; it reminds me of your trebly yet “scooped”-sounding 1970 tone that’s all over your first solo album [1970’s Eric Clapton], which includes your cover of Cale’s “After Midnight.”

Yeah, and it has a lot to do with that Bandmaster I'm playing through, and having everything wound up—the guitar pretty loud and the amp almost full. Sometimes I think it might be the way it was room-mic’d more than I normally would have it. So there'd be drums going in there too, you know. It makes the guitar sound different. So, if you’d put the mic right onto the amp for that track, it wouldn't have sounded like that, but I think the fact that the sound was swirling around the room gives it some of that character.

Is "Can't Let You Do It" another of the “legacy” Cale songs?

Yes, that was another one of these unreleased songs from the CDs his wife gave me. His version of that song is undoable. The other one, “Somebody’s Knockin’,” I think we actually improved on it. I hope Christine forgives me, but I think we kind of did it, in a way, better. But as for “Can’t Let You Do It,” his version is undoable. It’s like trying to do “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” or any James Brown song—and thinking you can improve it. There are certain people that have it down where it cannot be; you cannot impersonate it, you cannot improve on it.

You also cover Leroy Carr’s “Alabama Woman Blues,” which you’ve played in concert in the past. Around 12 years ago, you listed it as one of your 10 favorite songs of all time. What do you find so alluring about it—or at least about Carr’s original recording of it?

I think it was where it hit me in my own life. It was one of the first songs I heard as a teenager, not really knowing anything about Leroy Carr. But there’s something about the sadness of that song. There's a certain atmosphere to his recording. Something about it is so poignant, moving, simple and sad. My version is much more out there and upbeat, but you really should listen to Leroy Carr’s version.

At the other end of the spectrum, the album features a cover of Bob Dylan’s “I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine” from 1967’s John Wesley Harding. The accordion is so prominent that it reminds me of a long-lost track by The Band, another of your major influences. Was that intentional?

It’s funny—that wasn’t deliberate. We did that very quickly. I invited Dirk Powell, the accordion player, to come over and play with the pianist, Walt Richman. Walt comes from Tulsa and Dirk comes from Louisiana, and they’d never met. I just wanted them to play together in the room with me. That song is very significant for me.

It's another one of those things, sort of where I was in my life when I heard that Dylan album. All the songs on that album had a profound effect on me. It’s something about what he was doing with his life at that time and the way his musical taste was changing. I really was in total admiration because of the way he recorded it; it sounded like he walked into the room, started singing and everyone climbed on board. I wanted to have that atmosphere. So it wasn't deliberate. We weren't trying to mimic The Band, because I wouldn't know how to do that. I really wanted to pay tribute to Bob. He’s a big hero of mine.

And then there’s Robert Johnson’s “Stones in My Passway.” Although you’ve never officially recorded it until now, you played a solo-guitar version of the song on the Sessions for Robert J DVD in 2004. Around that time, you said it was a very difficult song to play because there’s a melody that’s happening beneath the vocal melody.

Yes, there’s a passage. If we talk about it in terms of a 12-bar blues, it’s in the second section. The first section is the A section; when you get to the B section, and you move up to the IV chord, there’s a phrase he plays underneath his vocal that I can’t do. I can’t sing it and play that phrase, and I will never do it, I don’t think. I think I’ve tried all my life to figure out how to do that—because the time signature of the singing is one way and the playing is another. They’re syncopated in very different ways. So it's always needed to be an ensemble piece. We did it well, but I'm still... Glyn would tell you I'm still not satisfied. I still think we could do it better. [laughs] You'll be hearing that again.

Which explains the approach you took on this new version of the song, where the entire band imitates, in a way, Johnson’s guitar—or acts as an extension of your guitar—just as they did on several tracks on 2004’s Me and Mr. Johnson. Also, “Stones in My Passway” is one of at least three songs on the album that originated in the Thirties. Is that something you planned?

I’m not sure. I think it’s because they were important to the people I was learning music from, which was my family. My grandmother, my mother and my uncle were very, very influential to me. They would sing all day long. They’d be buying records and listening to stuff, and a lot of it was early jazz and swing.

Paul Whiteman, Stan Kenton, the Dorsey brothers and a lot of those bands had singers, you know, like Frank Sinatra or Doris Day or Peggy Lee. So I heard all that stuff when I was knee-high. By the time I got to be 9, 10, 11, when I was starting to hear blues, I was already well-versed in popular music of the Thirties and Forties. I kind of knew it, especially Fats Waller. I was hearing black and white music—without knowing what was black or white—in my home, from my family. So these songs, there's a deep kind of a reservoir of that stuff that I’m still tapping into. I know Rod Stewart’s been doing that for a while. I just chuck a couple in every now and then. But there's some great stuff back there.

One of the Thirties songs on the new album is Al Hoffman’s “Little Man You’ve Had a Busy Day.” Does the song have any special significance?

Yep. My grandmother used to sing it to me as a lullaby. I know a lot of people I've talked to here in England about that, and they say they’ve never heard that song before. It’s difficult to find a decent version. I think Paul Robeson did a version and Bert Ambrose—the dance band leader—did a version. There are some really scaly ol' versions knocking around. I have it being sung by my grandmother a capella, which was fine for me. But I've always wanted to put that out there and give it back.

I've always kind of felt as though the yin and yang of your influences are Robert Johnson and JJ Cale. This album really seems to meld those two things pretty cleverly, as if you’ve found a natural way to combine them. It's a breezy form of music that's rooted in blues.

That's nice to hear, because that's how it kind of feels. I found a group of guys where we don’t need to talk; we can just play. I mean, there’s two groups. There’s a group of guys in America that I play with and a group of guys in England, so it’s as comfortable as it can be. They know what I want to do, and they know that, for me, it's about those two; Robert Johnson and JJ Cale is it. What more do you need, really? There's a lot of other stuff in between, like Muddy Waters, Little Walter and Howlin' Wolf. And there's the dance band legacy, with those beautifully crafted songs that still haunt me—and there will always be room for them. But I think you got it right.

There’s a lot of slide guitar on this album. Besides Robert Johnson, who were—or are—your slide influences?

Well, there are two other guys. There’s Elmore James; there’s something about his vibrato that I’m absolutely riveted by. He plays it so beautifully. The other guy is a Texan musician called Hop Wilson who played on records and in the clubs around Forth Worth in the Sixties and Seventies, I think. He played on a lap steel, so he played liked Robert Randolph, except he wasn’t “church,” he was blues, and I think he was unique in that respect. He plays some awkward tuning, I’m told; I think Jimmie Vaughan knows the tuning. It sounds to me like an open G or an open A, which leads me to play some of his phrases. I recommend you check him out. [Check out Wilson’s Houston Ghetto Blues on iTunes—Ed.]

There’s some talk that we’re primed for another blues comeback in the very near future. What are your thoughts on that?

Well, there's a guy called Blake Mills out there who's dabbling in all kinds of stuff. He is, for me, the premier musician in that field right now. He doesn't play blues for a living; he does a bit of film work and has made a couple of albums. But he's one of the finest slide players I've ever heard. It’s nice to know that someone is still moving in that direction.

What inspires you in 2016?

That guy! He's the guy. Just before we started talking, I went searching on iTunes to find stuff by him. He had an album out in 2014 called Heigh Ho, and now I’m getting a craving for some more, so I just found some film music by him. He's very inspiring for me. Gary Clark Jr. is also incredibly inspiring because he does what I’d like to do live without any effort at all.

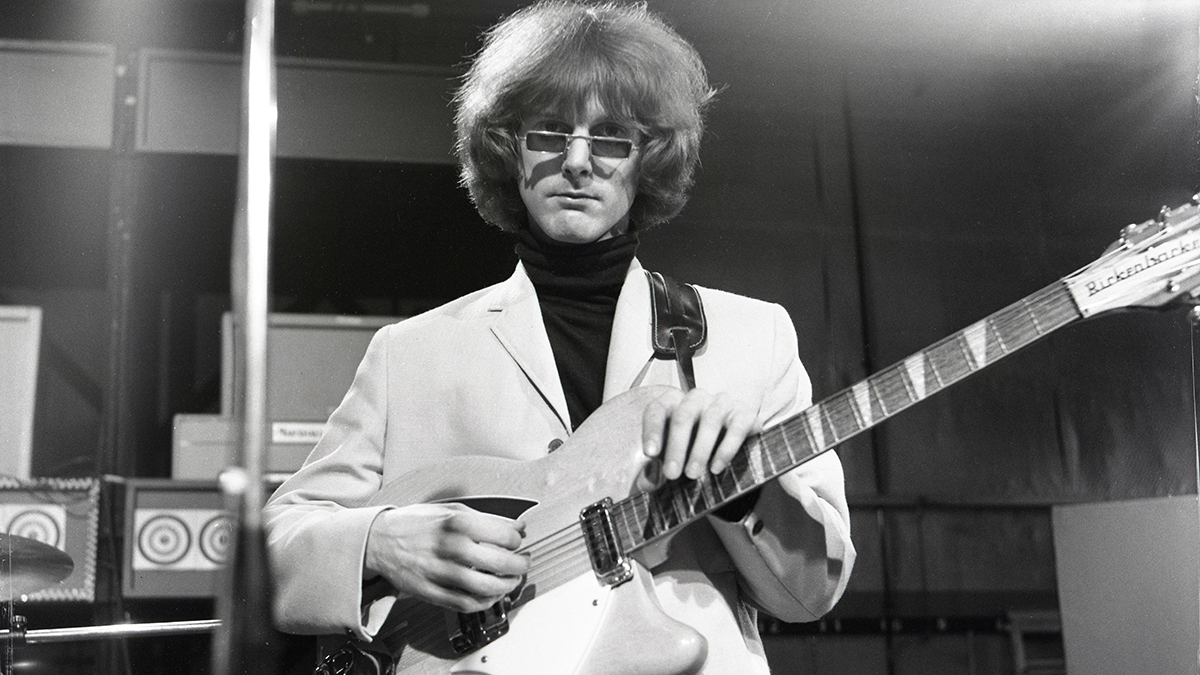

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton by John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, your first and only album as a member of that band. What do you think has made it such a classic?

I think what makes it so special is that it’s a recording of a band at work. We went into the studio and just played our set. There were no frills, no production value or anything. We just asked the recording guy to put the mics in the middle of the room and leave it to us. It was very refreshing, not because of what I did, but because there really wasn’t a producer. Mike Vernon was in the room, ostensibly producing, but he just let us do what we were gonna do.

Damian is Editor-in-Chief of Guitar World magazine. In past lives, he was GW’s managing editor and online managing editor. He's written liner notes for major-label releases, including Stevie Ray Vaughan's 'The Complete Epic Recordings Collection' (Sony Legacy) and has interviewed everyone from Yngwie Malmsteen to Kevin Bacon (with a few memorable Eric Clapton chats thrown into the mix). Damian, a former member of Brooklyn's The Gas House Gorillas, was the sole guitarist in Mister Neutron, a trio that toured the U.S. and released three albums. He now plays in two NYC-area bands.