Eric Clapton: The King and I

In 2004, Eric Clapton paid tribute to Robert Johnson with an album of the Delta King’s classic blues.

Back when he was a blues-obsessed teenager in England, something happened to Eric Clapton that caused him to fall down on his knees and ask the Lord above for mercy: he heard, for the first time, the music of Delta blues king Robert Johnson. Throughout his long and brilliant career, Clapton has often revisited that early encounter, likening it to “a religious experience” that “called to me in my confusion.” The depth and brutal honesty of Johnson’s music, he has said, “seemed to echo something that I had always felt.”

Not surprisingly, the emotions triggered in him by Johnson’s music also frightened Clapton a bit. “I could take the music only in small measures because it was so intense,” he recalls. Clapton immersed himself in the music but was also seduced by the Johnson mystique: the claim that he sold his soul to the devil in exchange for his musical prowess, the mysterious circumstances surrounding his death at the age of 27, and the lack, at the time, of even one photograph of the blues great. Clapton’s identification with Johnson was total, and not always benign: he admits, for instance, that he looked forward to dying in his late twenties.

Fortunately, as he battled and ultimately triumphed over his own well-publicized personal demons, Clapton came to focus more on the music than the mystique— on the Johnson who was “the best guitarist I ever heard,” the Johnson whose songs expressed “every angle of emotion.”

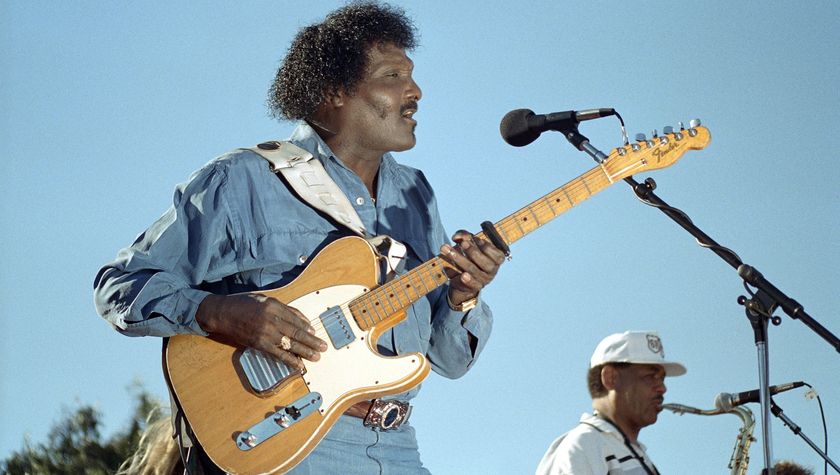

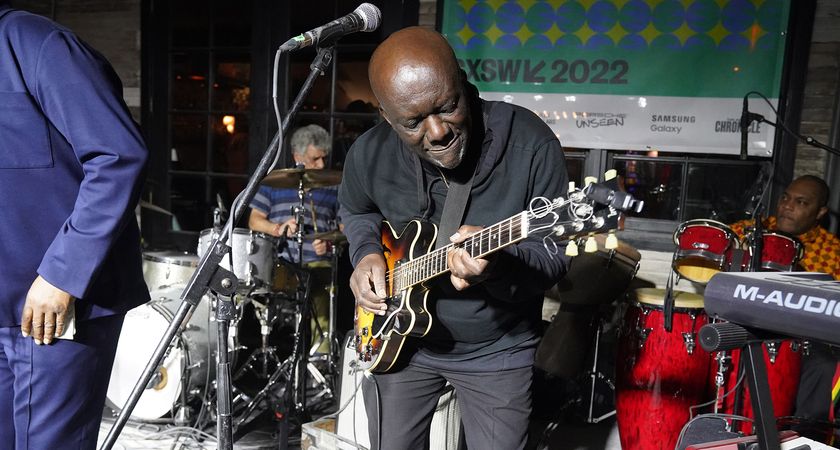

In 2004, Clapton at long last paid tribute to the great bluesman with the album Me and Mr. Johnson, an electric affair that featured brilliant guitar work by Clapton, his longtime collaborator Andy Fairweather-Low and Doyle Bramhall II. In the following interview, the Prince of the British Blues graciously consented to spin a verbal riff on the subject of his King.

GUITAR WORLD ACOUSTIC So you’ve finally taken the plunge and recorded an album of songs by Robert Johnson.

ERIC CLAPTON Yes. I realized that if I didn’t do it now I probably never would. What made it possible for me to do it in the first place was that I was no longer driven by any need to somehow match, or compete, with the originals. Also, the fact is that I’m very comfortable now in a way that I’d never been before. I think the primacy of my wife and children in my life had a lot to do with that.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

GWA It occurred to me that the very fact that the recordings on Me and Mr. Johnson differ so completely from Johnson’s own arrangements indicate a certain comfort level you had about the entire project.

CLAPTON That’s very true.

GWA I understand that your comfort in doing the material made it possible for you to record the material with a band. But why did you choose to not record any of the songs on Me and Mr. Johnson solo acoustic, just you and your guitar?

CLAPTON I actually tried to do “Terraplane Blues” solo acoustic, and it just sounded weak. There was no point in doing a second-rate version of a Robert Johnson song.

GWA When did you learn to play his music on the acoustic guitar?

CLAPTON To tell you the truth, I never really did; I have never actually sat down and played Robert Johnson unaccompanied. Even when I played “Malted Milk” on Unplugged, I did it as a duet with Andy Fairweather-Low. I can play pieces of Robert Johnson songs but not entire tunes note for note. I can play Big Bill Broonzy’s stuff, but there’s something very symmetrical about his music: once you learn the fingerpicking pattern, it’s easy. But Robert’s music is so asymmetrical, and there is always something new going on. I find it very difficult to play by myself.

GWA Johnson’s impact on you is well documented. I remember reading that as a young guitarist you often turned your back to your audiences when it came time to play a solo, and that this was associated with your obsession with Johnson.

CLAPTON I don’t know if this is true or not, but it was reported by Don Law, the man who recorded him, that prior to one of his sessions there were some Mexican musicians in the room with him. It seems he was unable to play in front of them; he had to turn and play to the corner of the room. When I read this I thought, That makes sense. How could he play in front of other people when he’s exposing his emotions so entirely?

GWA When you first discovered Robert Johnson, very little was known about him; he was a mysterious, romantic figure. Within the past three decades, however, two photos of Johnson were unearthed and blues scholars have learned much more about his life. Has that in some way diminished him in your eyes?

CLAPTON No, not at all. The music, which I digested and placed in a certain location a long, long time ago, is in a very safe place in my heart and mind. I could watch a documentary about his life with a great deal of interest, but it would have absolutely no effect on what I gathered from the music, then or now.

GWA Some revisionist blues historians have downplayed Johnson’s influence as a blues artist, maintaining that his importance was a creation of his later, white audience. Others point out that much of his material was actually derived from previous work by bluesmen like Son House, Lonnie Johnson and Kokomo Arnold. What’s your view?

CLAPTON I recently read Elijah Wald’s Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues, and he made what I thought were some pretty rash statements. One was that Robert could have been removed from the picture and nothing much would’ve been affected. I thought that was an extraordinarily hasty thing to say, and I’ll explain why: Before I heard Robert Johnson, I had already been exposed to a lot of rhythm and blues artists like Chuck Berry and Jimmy Reed. As soon as I heard Johnson play boogie on things like “When You Got a Good Friend” and “Rambling on My Mind,” I immediately understood where a lot of R&B grooves originated. No one else from that period—not Son House, not Charlie Patton, not Blind Lemon Jefferson— played anything like that. I think that was Robert Johnson’s invention, which is a considerable contribution to the blues, and it enabled me to make a direct connection from Robert Johnson to Jimmy Reed.

GWA I once read of a guitarist who described Johnson as a “one-man power trio” because of his penchant for simultaneously playing a bass line, a rhythm part on the middle strings and a lead riff on the treble strings, all while singing the song.

CLAPTON Yes, it was a natural thing for him to do, and I think that’s also his invention. You mention that while playing a line on the low strings he would simultaneously pick little reference notes on the high strings, something he does on “When You Got a Good Friend,” which we recorded on Me and Mr. Johnson. Well, Freddie King used to do that all the time, and I’ve heard countless electric guitar players do that. It was like Johnson was playing electric guitar before there were electric guitars; that’s the bizarre thing. And while I accept that he was a product of influences like Lonnie Johnson and Kokomo Arnold, I don’t think anyone summed up the whole Delta blues experience in the way—or had the impact—that he did.

GWA What would you say distinguishes Robert’s playing from that of his Delta bluesman peers?

CLAPTON He had finesse! I heard Johnson before I heard Son House and Charley Patton, and people kept telling me I had to check them out. When I did, my first reaction was, Whoa, these guys are kind of noisy; they’re kind of clanky! “Clumsy” is probably too harsh a word. But then I’d go back to Robert and think, There’s no comparison, this guy’s got finesse. His touch was extraordinary; it was so refined, which is amazing in light of the fact that he was simultaneously singing with such intensity.

GWA It must have been thrilling for you when, as a member of the Yardbirds, you played with Sonny Boy Williamson II, who reputedly knew Johnson quite well. Did you ever ask him about Robert?

CLAPTON No, partly because we became enemies on the first day we met. I went up to him and asked, “Isn’t your name really Rice Miller?” Of course, his name really was Rice Miller. I must’ve come off like some naïve blues collector. And our relationship never recovered after that. I think he thought I was making fun of him. Sonny Boy was a very difficult and strange man.

GWA Did you actually learn anything from this “difficult and strange” bluesman?

CLAPTON While we didn’t get along, he did make me realize how important it was to pay attention to detail in the blues. For example, the Yardbirds would be rehearsing with him, he would call out one of his songs—like “Nine Below Zero”—and we would start playing. Suddenly, he would stop and say, “That’s not how you play it.” And the other guys in the band would say, “What do you mean—it’s a blues, isn’t it?” But I had heard the record and knew that there was actually an intro, a motif, a balance of who played what, and that we weren’t playing those things correctly. I suddenly became aware through working with him that even though you had this general thing called “the blues,” each song had its own identity and had to be rehearsed and respected. We were very young and just didn’t know any better. The truth is he had every right to be upset. We were supposed to be playing his hit songs and we just didn’t learn them properly. I would not be very happy myself if I was playing with a bunch of musicians who didn’t bother to learn all the parts to my songs.

GWA Is there anything else about Robert or his music that you didn’t get in your youth but which you now understand?

CLAPTON God, you stumped me. I don’t think there’s anything I understand more about him now than I did then. I may be a little more comfortable playing his music now, because it’s very much part of who I am, but that’s about it. When I was a teenager, I could take the music only in very small measures because it was so intense. But do I grasp it any better? I’d have to say that I don’t: it’s as mysterious to me now as it ever was. I still don’t know how he did some of that stuff. Take “Kindhearted Woman Blues”: there’s an instance in one of the verses, on a IV chord, where he plays an odd single-note kind of accompaniment behind the vocal. I can’t do it—I can’t see how anybody could do it. [laughs]

GWA Once the greatest, always the greatest.

CLAPTON No question about it.

“I get asked, ‘What’s it like being a one-hit wonder?’ I say, ‘It’s better than being a no-hit wonder!’” The Vapors’ hit Turning Japanese was born at 4AM, but came to life when two guitarists were stuck into the same booth

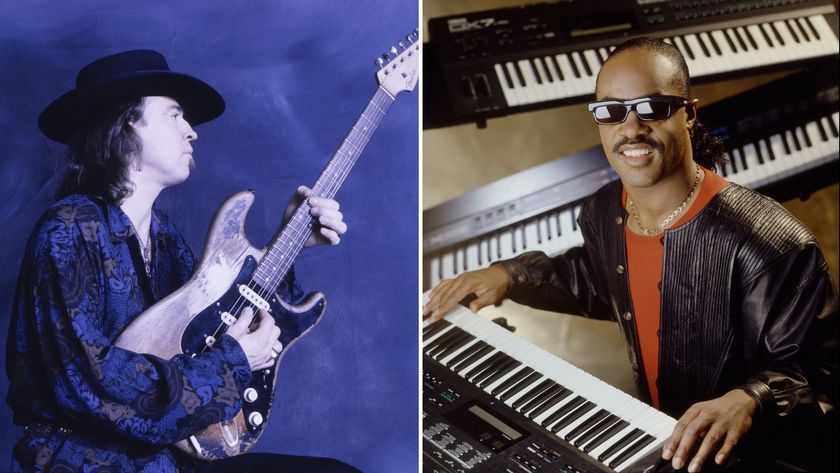

“Let's play... you start it off now, Stevie”: That time Stevie Wonder jammed with Stevie Ray Vaughan... and played SRV's number one Strat

![[L-R] George Harrison, Aashish Khan and John Barham collaborate in the studio](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/VANJajEM56nLiJATg4P5Po-840-80.jpg)