Eric Clapton's 10 Best Guitar Moments

There was a time when the name Eric Clapton meant one thing and one thing only: guitar god.

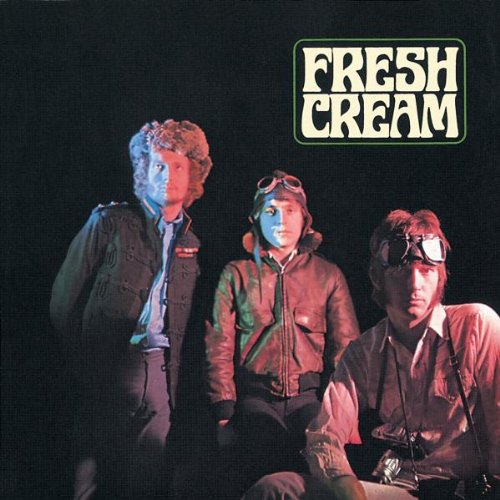

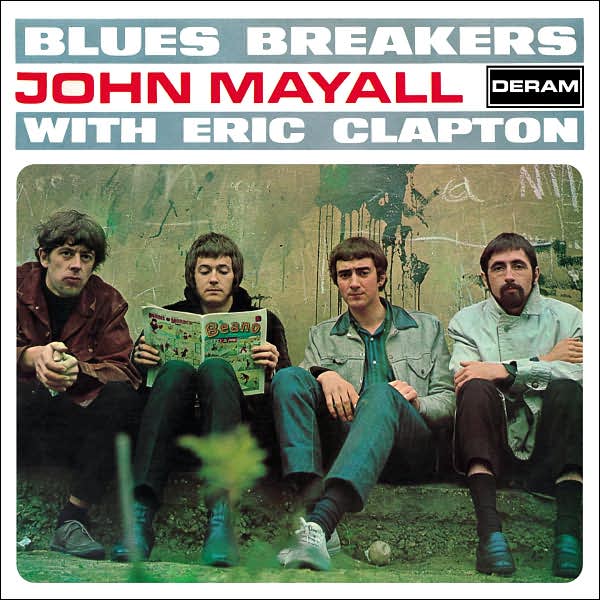

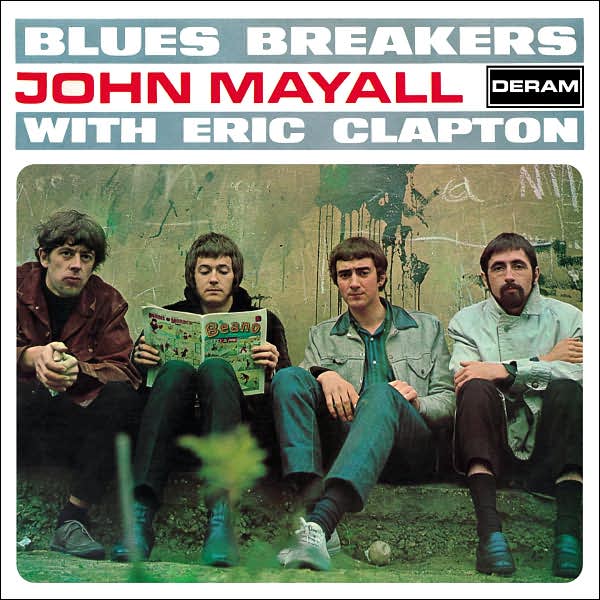

His six-string exploits with the Yardbirds, followed by a pair of mind-blowing 1966 albums—Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton and Fresh Cream—briefly put the passionate young Clapton atop the U.K.’s, if not the world’s, guitar hierarchy.

By the late Sixties, he was sharing the spotlight with such rock deities as Jimi Hendrix, Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck. Significantly perhaps, it was around this time that Clapton began incrementally distancing himself from the flashy, lengthy solos of his wild youth, as he segued from Cream to Blind Faith, and then from Derek and the Dominos to a successful solo career. He eventually fell under the mellow spell of J.J. Cale and the Band, put more emphasis on singing and songwriting, and dabbled in country rock, reggae, acoustic music and ultra-slick pop tunes.

Today, Clapton enjoys an enviable spot as one of the most respected elder statesmen in rock and blues. And although he happily handed over the guitar-god mantle decades ago, he’s not averse to melting a few faces when the opportunity arises. Guitar World looks back at Clapton’s 50-plus-year career and pinpoints what we consider to be the 10 greatest guitar moments—thus far. Our list digs deep into his six-string artistry, putting the emphasis on the playing and not necessarily the hits.

We hope you enjoy this guide to Clapton’s cream of the crop. If you'd like to delve a lot deeper into this subject, we recommend E.C. Listening: Eric Clapton's 50 Greatest Guitar Moments. Enjoy!

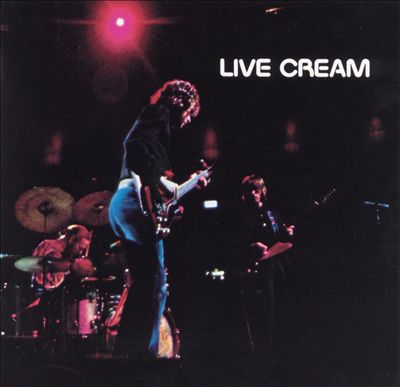

10. "Sleepy Time Time" Cream—Live Cream (1968)

Cream’s initial inspiration grew from their dedication to a trailblazing, group-improvisational reinvention of blues forms, including Willie Dixon’s “Spoonful” and Skip James’ “I’m So Glad.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

This track, which they originally cut in the studio for their late-1966 debut, Fresh Cream, offers bassist Jack Bruce’s singularly twisted view of a swinging 12/8 “modern” blues in a more condensed but no less cutting-edge form, as compared to the 15-plus-minute jams that highlighted Cream’s performances. Live Cream combines four tracks recorded March 7–10, 1968, in San Francisco at the Fillmore West and Winterland Ballroom, plus one studio outtake, “Lawdy Mama.”

Cream played a staggering 200 shows in 1967 and, after just two weeks off, resumed an equally grueling schedule from the very start of 1968. This LP captures them during their 223rd to 226th performances in just 14 months, so it’s no wonder they achieve the purely magical in-sync group improvisation displayed on this track and in evidence throughout this album. Playing through a pair of 100-watt Marshall stacks (using the 1960A and 1960B “tall” 4x12 bottom cabinets), Clapton produced a massive sound.

There is debate over which guitar he used on specific live recordings, as he alternately played his 1964 “The Fool” Gibson SG, 1964 Firebird I and 1963 ES-335 during this period, though some photos from the 1968 tour show him with a Les Paul. Clapton’s soloing here evokes the influence of B.B. King as he moves deftly between phrases based on C minor pentatonic (C Eb F G Bb) and C major pentatonic (C D E G A). His lightning-fast hammer-pulls and heavenly “floating” vibrato illustrate why the 23-year-old Clapton was called God during this period.

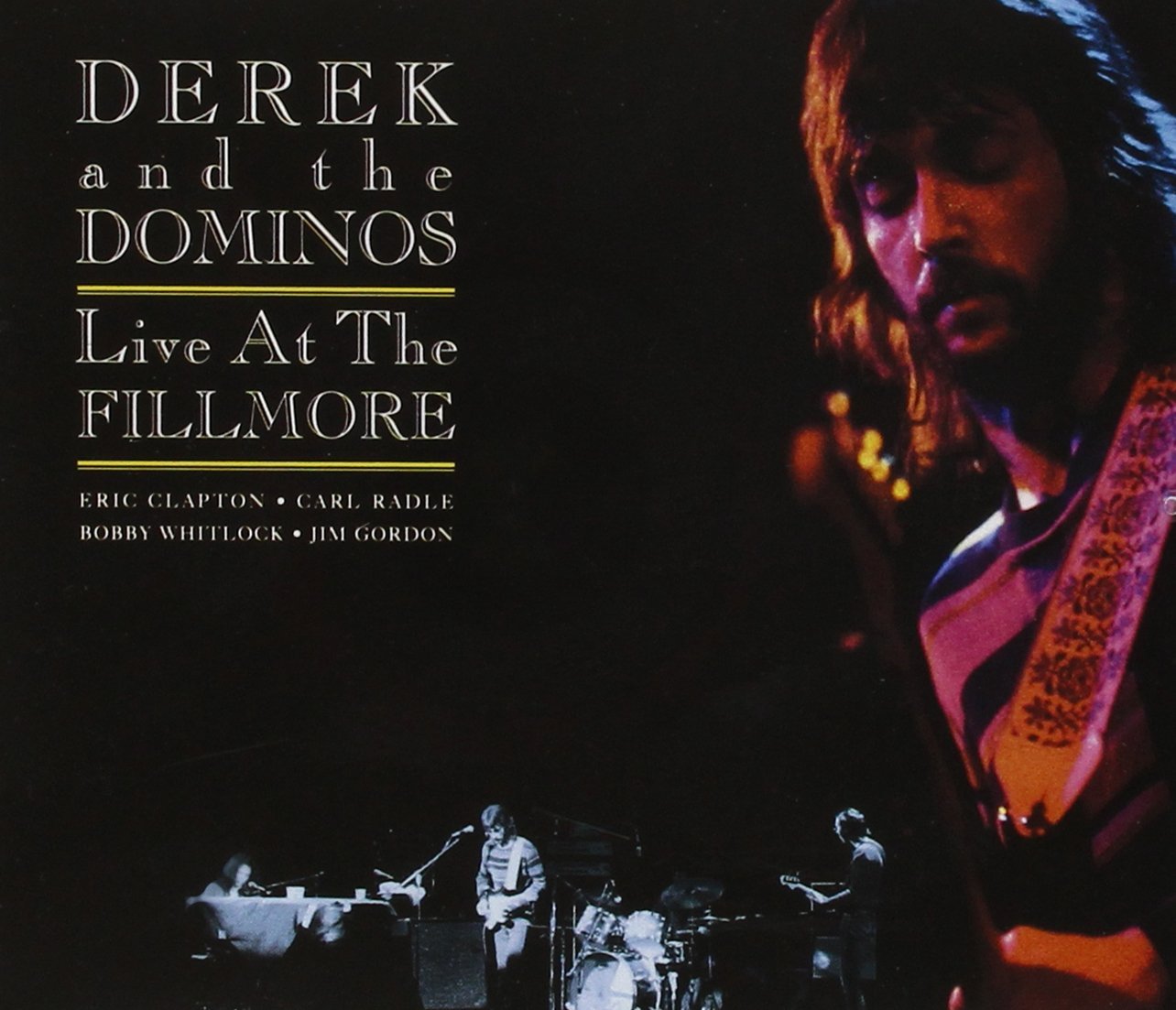

09. "Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad?" Derek and the Dominos—Live at the Fillmore (1994)

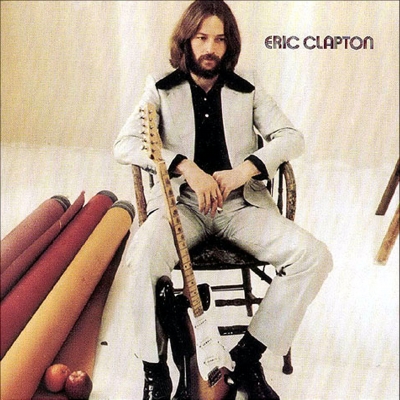

In 1969, following the implosion of Cream and the short-lived Blind Faith, Clapton found himself at a career crossroads. Disillusioned and directionless, he joined the powerhouse husband/wife-led Delaney & Bonnie and Friends as a sideman, and by that summer he appropriated Delaney Bramlett (with his entire band in tow) to produce his first solo release, Eric Clapton.

Three musicians from this lineup—bassist Carl Radle, keyboardist and singer Bobby Whitlock and drummer Jim Gordon—formed the nucleus of Clapton’s next band, Derek and the Dominos, who recorded the seminal Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs in the summer of 1970 and toured as a four-piece through August. The Dominos’ live shows were filled with long jams, and at nearly 15 minutes, “Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad?” was one of the longest, opening with an extended wah-infused funk workout. With stellar high-harmony vocals added by Whitlock, this four-piece emits a huge sound. Clapton’s first solo has all the fire, fury and melodicism of his greatest playing, his 1956 “Brownie” Stratocaster screaming pure virtuosity and conviction.

The second half of the song is a seven-plus-minuteD major jam during which the 25-year-old guitarist displays inspired chordal and single-line inventiveness.

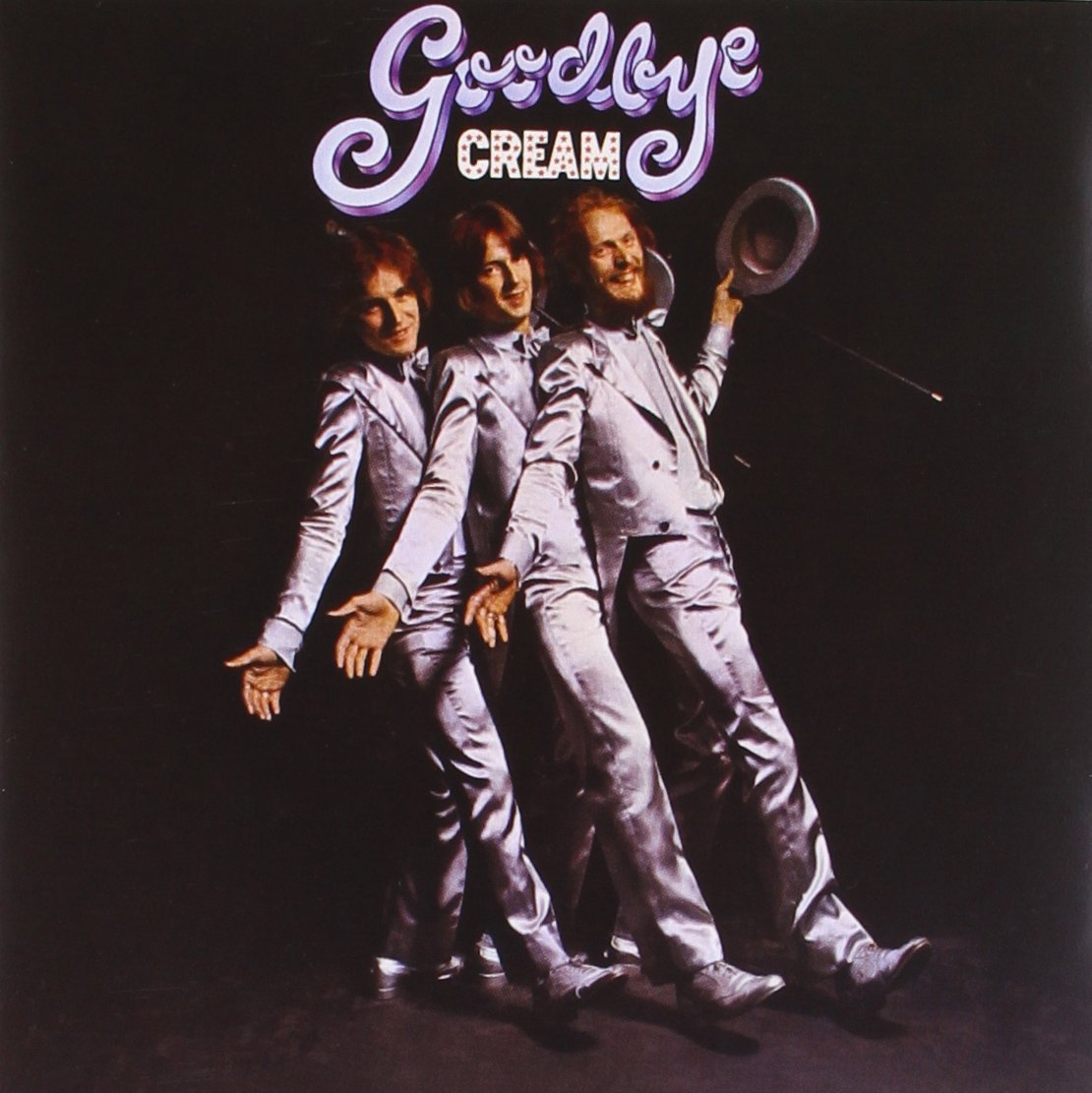

08. "Badge" Cream—Goodbye (1969)

Much like “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” Cream’s “Badge” is the result of a strong and ultimately long-lasting friendship between Clapton and the Beatles’ George Harrison.

When Cream decided to call it quits in late 1968, each member of the band, including Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker, was required to come up with a new song for the group’s final album, Goodbye, the remainder of which would be filled with live cuts. Clapton called on Harrison for assistance.

“I was writing the words down, and when we came to the middle bit, I wrote ‘Bridge,’ ” Harrison said. “And from where [Eric] was sitting, opposite me, he looked and said, ‘What’s that—Badge?’ ” Clapton wound up calling the song “Badge” because it made him laugh. For the session, which took place only a month after “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” Harrison played rhythm guitar. Clapton, playing a shimmering, Beatles-inspired arpeggio riff through a Leslie rotary-speaker cabinet, enters the song at 1:06 and plays the rest of the way through. His guitar solo was overdubbed later.

The brilliant solo, which lasts a cozy 33 seconds, is a prime example of a “composition within a composition.” It finds Clapton sending his considerable blues chops through a pop-rock funnel, something he’d do on and off for the next 46-plus years.

07. "Spoonful" Cream—Fresh Cream (1966)

Just as “Crossroads” introduced a new generation of music fans to the mystique of Robert Johnson, Cream’s “Spoonful” brought extra exposure to Willie Dixon, who wrote the song, and Howlin’ Wolf, who originally recorded it in 1960.

And while Howlin’ Wolf’s stark-and-dark version is haunting in its own right, Cream’s take on the song—driven by Clapton’s guitar and Jack Bruce’s heavy bass—moves it several steps further along. Clapton’s solo, which starts at 2:23, seems almost playful at first, as if he’s toying with the listener, but at 2:46, things take a sudden and profound turn toward the dramatic. He plays a series of notes—virtual howls and moans—high on the neck, punctuating them with several perfectly timed cracks at his low E string.

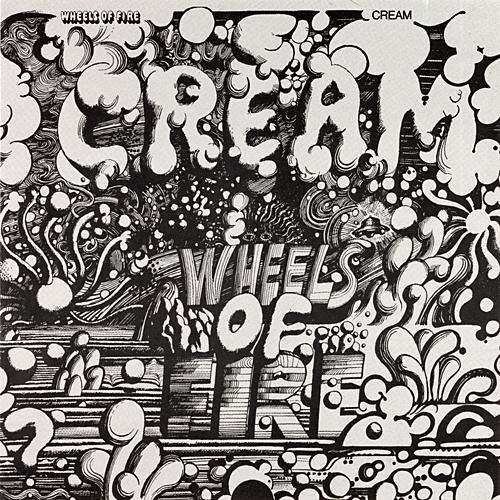

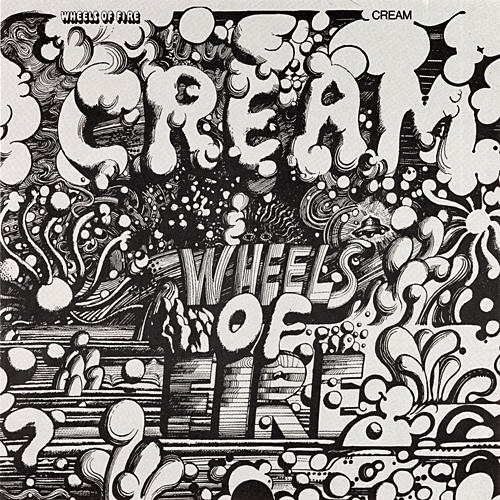

At 3:31, he launches into a completely new melody, taking Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker along for the ride. Clapton’s tone on the track, a unique dense, reverb-drenched sound that only a Gibson humbucker could produce, stands alone in Cream’s canon and in Clapton’s entire discography. At Cream’s live shows, “Spoonful,” like several other songs, gave the band members plenty of room to stretch out, as can be heard on the sensational, nearly 17-minute-long version on Cream’s Wheels of Fire.

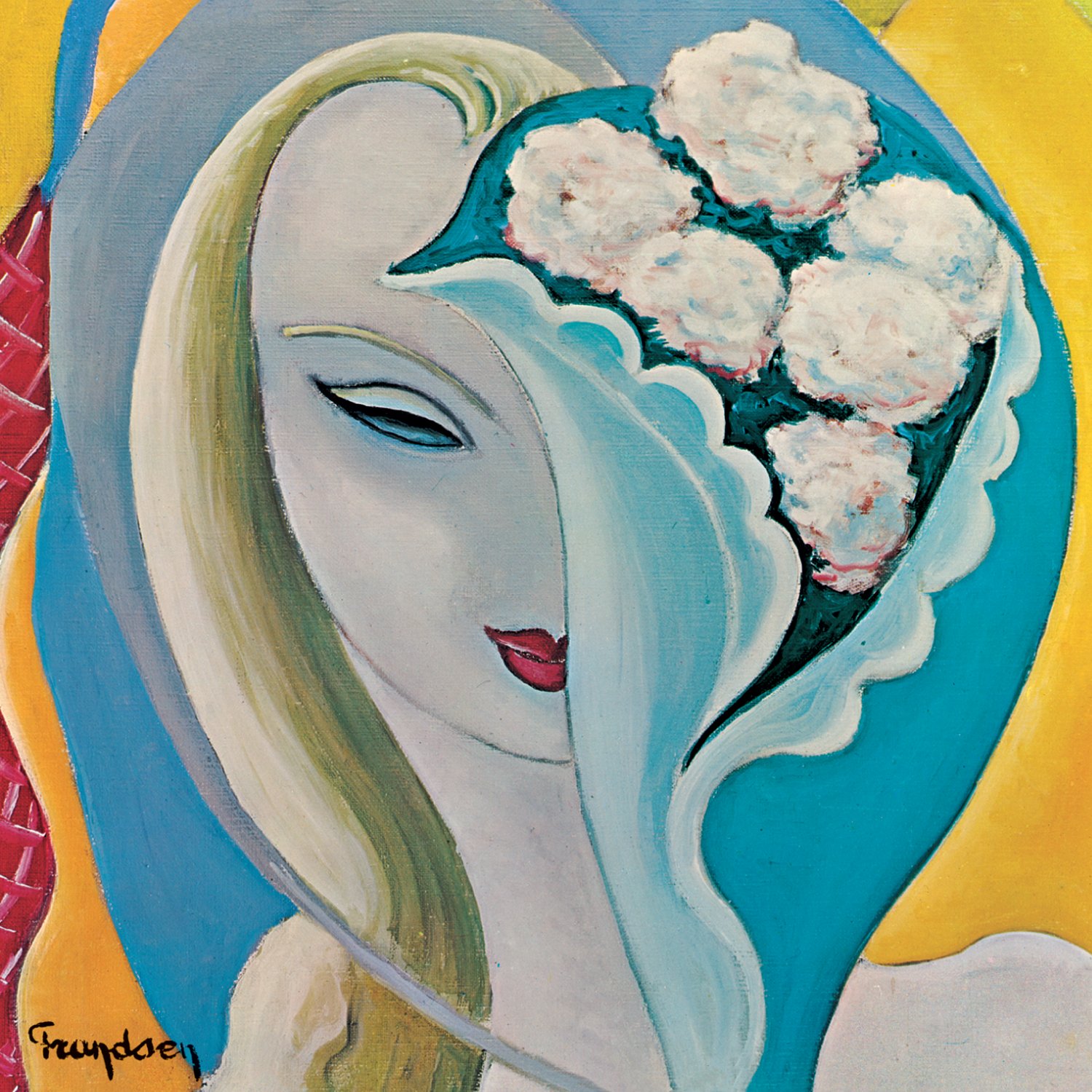

06. "Layla" Derek and the Dominos—Layla (1970)

Having played with several of the most influential bands of the Sixties, Clapton launched the Seventies with a new group of his own devising, Derek and the Dominos.

He wrote this tune—the title track of their debut album—to express his unrequited love for Pattie Boyd, who was George Harrison’s wife at the time but would leave Harrison for Clapton later in the Seventies. The song’s killer main riff was something Clapton cooked up with legendary guitarist Duane Allman, who guested on the Derek and the Dominos sessions at the suggestion of producer Tom Dowd. The unusual half-step downward modulation from the D minor main riff/chorus key signature to the verses, which are in D flat minor, enhances the despairing mood of Clapton’s lovelorn lyric.

There’s a deep sense of musical telepathy in the way his bluesy Strat lines interweave with Allman’s eerily spectral slide guitar improvisations during the song’s extended solo over the main riff structure. This gives way to the track’s stately piano-driven coda, penned by Dominos drummer Jim Gordon and affording Allman and Clapton even more real estate over which to stretch out.

05. "Let It Rain" Eric Clapton—Eric Clapton (1970)

This tastefully arranged song from Clapton’s debut solo album begins with the guitarist overdubbing a sweet-sounding mini choir of three harmony-lead guitars with perfectly synchronized finger slides and vibratos.

Together they create the effect of one instrument playing a melody harmonized in triads, but with the brightness and clarity that can only be achieved by three separate single-note lines, or “voices.” Clapton recorded this song on Brownie, his Fender Stratocaster, using its bright single-coil bridge pickup for his lead parts to achieve a brilliant tone and crystal-clear note definition. Clapton’s solo over the song’s outro features his signature polished finger vibrato and use of parallel major and minor pentatonic scales (both in the key of A in this case).

He begins by riding out on the high A root note on the high E string’s 17th fret with alternate-picked 16th notes. Clapton then proceeds to travel down the string through the A Mixolydian mode (A B C# D E F# G)—a distinctly different approach to position playing—before gravitating toward A major pentatonic box shapes, using multiple hammer-ons and pull-offs to create a succession of repetition licks with syncopated “threes on fours” rhythmic phrasing that creates an almost banjo-like country feel. While Clapton’s lead tone here is markedly brighter than what he used earlier in his career, his unique style, as determined by his phrasing, string bending and vibrato, remains his signature.

04. "Steppin’ Out" John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers—Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton

“Steppin’ Out” is one of Clapton’s best-known Bluesbreakers tracks, and with good reason.

Along with “Hideaway,” it delivers the heftiest dose of Clapton’s solid, mind-blowing tone and ferocious playing. This upbeat, straightforward blues instrumental in G finds him borrowing bits and pieces from Memphis Slim’s original 1959 version. Clapton (along with John Mayall on keyboards) plays the figure from Slim’s piano intro and then references the track’s tenor sax solo. At the 54-second mark, he incorporates an ingenious “scraping” technique from the original guitar solo, which was played by Matt “Guitar” Murphy, who would go on to join the Blues Brothers Band in the late Seventies. But there’s a lot more going on here.

Clapton incorporates some serious finger vibrato on the 12th fret of the G string—which only adds to the sustain produced by his overdriven Marshall amp—and he uses finger slides as he shifts between several positions of the G minor pentatonic scale. The well-paced solo ends with Clapton, much like his idols B.B. King and Buddy Guy, bending high on the neck before returning to the intro figure.

It’s worth noting that he recorded other versions of “Steppin’ Out” with his short-lived 1966 supergroup the Powerhouse and with Cream, including the knockout 14-minute version on Live Cream Volume II.

03. "White Room" Cream—Wheels of Fire (1968)

Penned by Cream bassist Jack Bruce and Swinging London poet Pete Brown, “White Room” provided a suitably glorious opening track for Cream’s third album, 1968’s Wheels of Fire.

From the first notes of the song’s 5/4 bolero intro, it’s clear that this is a landmark recording. Clapton’s mysteriously evocative layered guitar textures set a mood of high drama before the main 4/4 groove kicks in with an irresistible invitation to some serious hippie-era proto-head banging. The descending D minor verse progression is reminiscent of Cream’s earlier epic track “Tales of Brave Ulysses,” which is said to have been based on the chord pattern in the Lovin’ Spoonful’s 1966 hit “Summer in the City.”

“White Room” contains some of Clapton’s finest wah-pedal artistry. He employs the device to create fluttery, aquatic magic in the choruses and to answer Bruce’s verse vocal lines with incandescent leads that match the fevered intensity of Brown’s lyrical imagery. Breaking with the time-honored tradition of putting a guitar solo in the middle of a song, “White Room” waits for the outro fade to unleash the full fury of Clapton’s slashing, psychedelic blues-wah frenzy. Clearly, they saved the best for last.

02. "Have You Heard" John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers—Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton (1966)

Quite frankly, if Clapton’s “Have You Heard” guitar solo doesn’t cause heart palpitations, shortness of breath or at least a mild case of goose bumps, you might want to seek medical help.

The dramatic, 73-second pentatonic masterpiece is hands down the most frenetic, passionate solo of the guitarist’s 51-year career. The solo, which bursts out of the starting gate at the 3:25 mark, strings together a series of spectacularly intense, incendiary bends, hammer-ons, strategically timed position shifts, and slides. Clapton caps it off with a bevy of climactic high notes, an earmark of his solos on Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton.

All of it is delivered via his groundbreaking new sound, a solid, sustained, overdriven tone that he forged by plugging a 1960 Gibson Les Paul Standard into a 42-watt Marshall 2x12 combo and cranking it up to ear-splitting levels.

On the album, Clapton burns and bedazzles like a futuristic amalgam of his many influences, including Freddie King, Otis Rush, Hubert Sumlin and Buddy Guy. Amazingly, Clapton was only 21 (about to turn 22) when Blues Breakers was recorded in March 1966. Even if he had simply vanished or faded away after the release of the album that summer (much like his stolen and still-missing 1960 Gibson Les Paul Standard), he still would have earned a respected place in the annals of electric blues guitar.

01. "Crossroads"Cream—Wheels of Fire (1968)

“Crossroads” has long been regarded as Eric Clapton’s most inspired and well-crafted lead guitar performance, and with good reason.

This live, highly reworked cover of Robert Johnson’s “Cross Road Blues” features him and band mates Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker performing some intense—and extended—interactive jamming on a 12-bar blues in A, set to an uptempo, double-time groove with a driving even-, or “straight-,” eighths feel. The high point comes during the arrangement’s second, prolonged guitar solo, when the group engages in a rhythmically dense improvisation that represents the exhilarating apex of blues-rock freeform jamming.

Conjuring a killer creamy tone with his 1964 Gibson SG Standard and stacks of 100-watt Marshall amps, Clapton exploits the rig’s available sustain, using his signature vocal-like finger vibrato technique to make his guitar sing. Particularly noteworthy is Clapton’s consistently wide and impeccably intonated bend vibratos (bent notes that are then shaken), especially during his upper-register second solo, which he plays mainly in the 17th-position A minor pentatonic (A C D E G) “box” pattern.

He combines notes from this scale with those from the parallel A major pentatonic (A B C# E F#) to create varying hues of melodic “light and shade,” more so during his first solo, and seamlessly shifts/drifts from one position to the next by using legato finger slides. The result is a performance that ably supports the then-popular declaration that Clapton is God. “Crossroads” maybe a song about striking a deal with the Devil, but this recording shows Clapton in supreme command of his divine powers.

“I suppose I felt that I deserved it for the amount of seriousness that I’d put into it. My head was huge!” “Clapton is God” graffiti made him a guitar legend when he was barely 20 – he says he was far from uncomfortable with the adulation at the time

“I was in a frenzy about it being trapped and burnt up. I knew I'd never be able to replace it”: After being pulled from the wreckage of a car crash, John Sykes ran back to his burning vehicle to save his beloved '76 Les Paul