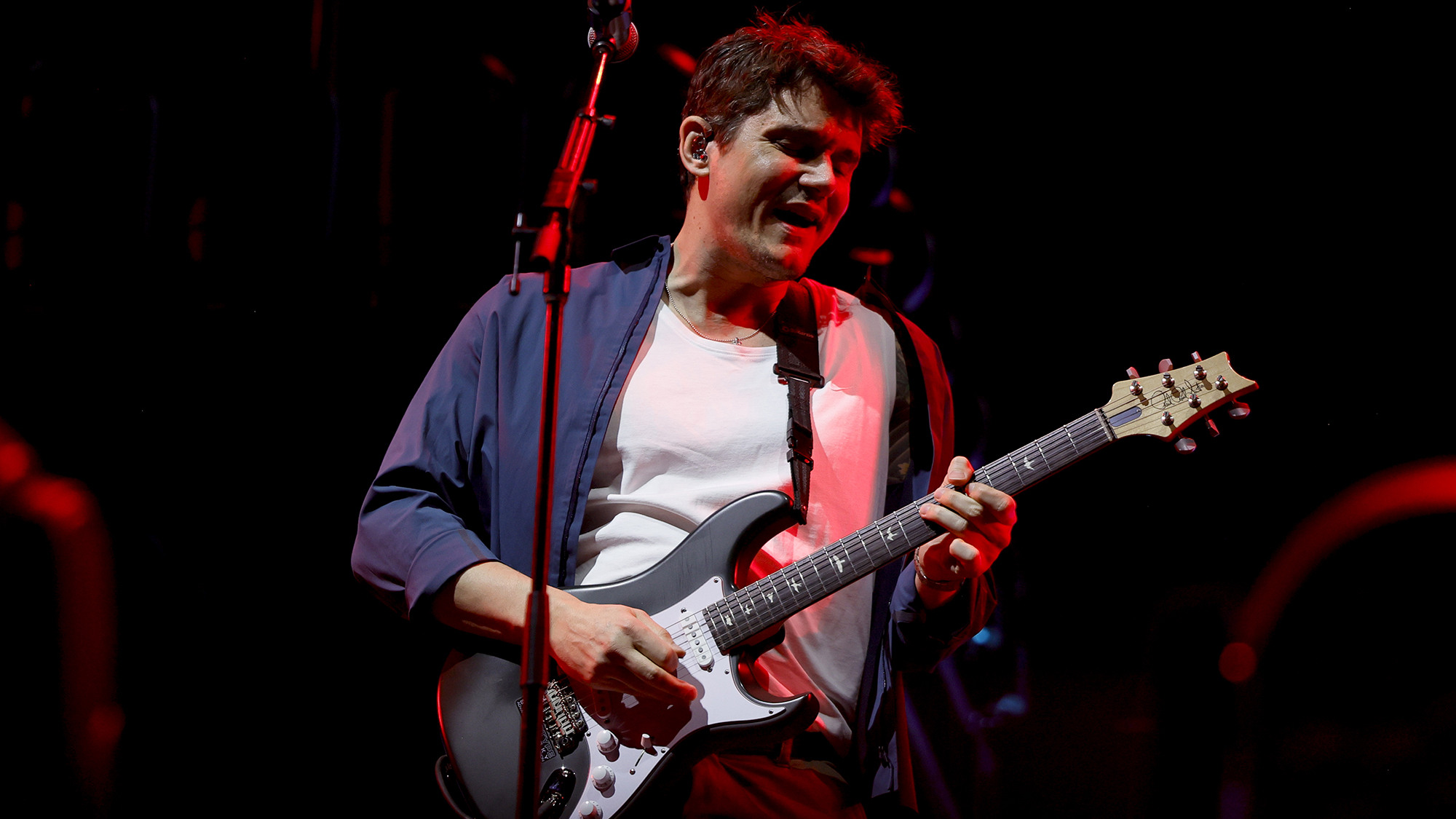

Electric Cowboy: Brad Paisley

The inspiration for the title of Brad Paisley’s latest album Wheelhouse came from the phrase “in your wheelhouse,” which is a reference to the baseball term for the strike zone’s sweet spot, where a batter can comfortably hit a ball with maximum power and precision. However, “wheelhouse” also refers to a rotating track switching platform in a rail yard that enables the movement of a train engine to tracks going in various directions. Each of these definitions apply to Paisley’s new album, as he delivers the fine-crafted, home-run hit country tunes that have made him one of country’s biggest stars over the past decade as well as a few unexpected curveballs that will take his fans by surprise.

With Wheelhouse, Paisley is entering a significant new chapter in his career, which from the beginning never really followed the typical Nashville formula. In the tradition of Merle Haggard and the Strangers or Buck Owens and the Buckaroos, Paisley has always recorded with the same band that he tours with—an uncommon practice these days when most artists record with Nashville’s deep well of studio musicians. This time, Paisley pushed the envelope even further by producing the album himself and recording it in a studio he built in a farmhouse a short walk down the hill from his home located in an idyllic, remote countryside setting outside of Nashville.

Like the rail yard wheelhouse, the album takes listeners in many different directions. There’s the soaring melody of the first single, “Southern Comfort Zone,” followed by progressive bluegrass overtones of “Beat This Summer” and “Outstanding in Our Field,” a stomping rocker certain to become country’s summer party anthem of 2013. “Pressin’ on a Bruise” delivers a taste of Waylon Jennings’ phase-shifted Tele twang, while “I Can’t Change the World” pairs a sweet ballad with Radiohead-style dub delay feedback. Comedic relief comes from the songs “Karate,” “Death of a Married Man” (featuring Monty Python’s Eric Idle) and “Death of a Single Man,” contrasted by the serious message of “Accidental Racist” with its guest rap by LL Cool J.

The one common string throughout the entire album is Paisley’s tasteful guitar playing, which could be considered his sweet spot power-hitter comfort zone. As the album’s producer, Paisley was unleashed from any reins that might have previously held his guitar playing back, but wisely, he didn’t overindulge. Every song and solo has its fair share of “how did he do that?” moments, but he offers just enough to please guitar geeks without alienating his less instrumentally inclined listeners.

As Paisley gives a tour of the studio, pointing out his pair of Trainwreck amps (a Liverpool “Hattie Mae” and a Rocket “Marcy”), discussing his preference for Mogami cable and waxing poetic about his Catalinbread Montavillian Echo pedal, he reveals how his passion for the guitar still remains his driving force. As we settle down to talk, he picks up his trademark 1968 Fender Telecaster, featuring a glowing, aged paisley finish, and plays passages from the album, using his guitar as much as his words to explain what he wants to say. While much of Paisley’s fame stems from his talents as a singer, perhaps his most eloquent musical statements, particularly on Wheelhouse, are his guitar solos, whether it’s the moody introspection of “I Can’t Change the World” or the bursting-at-the-seams exhilaration of “Runaway Train.”

- Country music’s history is filled with dozens, perhaps even hundreds, of incredible guitarists who all placed their own unique stamp on the genre, but these days guitarists who carry on that tradition like Paisley rarely break through to the mainstream. His continued and growing success gives hope to aspiring guitarists—not just country players but from all styles of music—that the days when every great band had a great guitarist that plays great solos may return.

- And even if those days may be gone for good, it’s reassuring to know that Paisley still will be cranking out solos and licks that push the boundaries of great playing a little further and keep us all reaching for new ideas and inspiration.

What made you decide to become a guitar player?

My grandpa used to sit in a chair and play every day. He was a big fan of instrumental music, so I grew up listening vicariously to Chet Atkins and Les Paul. Most kids my age had never heard of them. He really liked country music and listened to a lot of Buck Owens and Johnny Cash. My grandpa was opinionated. He didn’t like certain kinds of music, especially if it didn’t have interesting playing in it. He wasn’t a fan of easy listening, and really, neither am I. I like songs that make you think, or songs that have incredible playing in them. It has to have great lyrics or playing—at least one of those two. He probably was the biggest musical influence in my life. One day he placed a guitar in my hands and said, ‘This will always be something you can use as an escape, a crutch, or to keep from being lonely.’ He was right.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What else inspired you then?

I was lucky that I came from an area that was big on music. In Wheeling, West Virginia, we had the Wheeling Jamboree, which was an old, well-known hotbed of music, although it’s not as influential or popular as it used to be. When I was growing up it was still a regular radio show on the weekends, a lot like the Opry. It’s even similar in age: it started in 1933, while the Opry began in 1925. If the Jamboree had come first, I might not have needed to move. I would have grown up in the right place. There were great players there, a thriving club scene, and festivals that you could play. It would be things like Charlie Daniels one weekend, George Jones the next, Little Jimmy Dickens, Steve Wariner, Vince Gill—all these great country artists would come through town. At that point country artists weren’t playing in arenas, other than Kenny Rogers, Alabama, and George Strait. Everybody else would play the Capitol Music Hall, which is where I also played as a regular from about the time I was 13. The capacity is about 2,500 seats.

Did you listen to other types of music beyond country?

I grew up during the Eighties when, for better or worse, most bands were centered around the guitarist. Every band had at least one household name guitarist, like Eddie, Nuno, C.C., Richie, Jimmy Page or Joe Perry. Every band had a great guitarist, and every guitarist had his moment to show off in every song, many times shamelessly, with no regard to subtlety, which I loved. I’ve gotten criticism on my records for throwing notes into songs, but that’s what I like. In each song you’ve got to blast listeners with something that’s hard to figure out. That’s what keeps it interesting for me. To this day when I go out on tour I don’t get bored playing my hits because I still have those moments where I can improvise.

The Eighties was also a good time for country. You had artists like Ricky Skaggs with Ray Flacke playing the Tele, Dwight Yoakam with Pete Anderson, and the Desert Rose Band with John Jorgenson, who became my favorite guitarist of all time. There was some great musicianship back then. People had unique styles and sounds. Even the female artists had their own thing going on. Mary Chapin Carpenter did some great stuff with her producer, John Jennings, on guitar, like “Down at the Twist and Shout” and “How Do.” Also, there was a lot of live music on TV. You could watch the Nashville Network and see bands on Nashville Now or New Country. Austin City Limits was in its prime. You had live performances all the time on The Tonight Show. It was easy to see someone play on TV.

I also hear a little bit of jazz in your playing.

Jazz is really important to country guitar. Country is jazz on the back pickup. When you switch your Tele from the neck pickup to the bridge and play the same lick, it’s instantly twang. Players here in town like Redd Volkaert, Johnny Hiland and Brent Mason really opened my eyes. They showed me that you can be a total monster. My main influence in my hometown was a guy named Hank Goddard, who was called Hank because he was so similar to Hank Garland. He was my main lead player and teacher for my first 10 years as a player. He taught me how to play “Birth of the Blues” and “Cannonball Rag” and how to solo over changes. At 12 years old, I was soloing over progressions like I-VI major-II major-IV. It wasn’t pentatonic scales over I-IV-V 12-bar blues. Instantly you have to figure out which scales and modes fit with that and figure out how to get around the neck without being stumped. It was such an interesting challenge to solo over jazz changes, and it was important for me to learn how to do that. I didn’t feel that I would be worth anything as a player until I knew my way around some jazz stuff. I’m not so sure players still feel that way today.

Most of the early, great country guitarists like Hank Garland and Jimmy Bryant loved to play jazz.

There isn’t a single jazz guitarist out there who isn’t blown away by Garland’s Jazz Winds in a New Direction. He could go toe-to-toe with anyone. That’s the thing about this town: we’ve always had players who are on the same level as the best players anywhere. Nashville is still about the most vibrant music scene in the world. If you don’t like what you’re hearing, just seek out something different, because it’s here. If you don’t like modern music you can go to the Station Inn and check out the Time Jumpers with Vince Gill, or go to a songwriter night at the Bluebird Café and hear what people are writing before it’s produced. Nashville is great that way.

This album’s title, Wheelhouse, refers to a comfort zone, and the first single is even called “Southern Comfort Zone,” but you really went beyond your own comfort zone on the record. This is almost like a concept album that takes you on a journey.

More than any other album I’ve ever made, this album really works beginning to end. There aren’t any lulls. You don’t find yourself wishing that this song came first or that another song was somewhere else. It goes through a journey of fun moments, dark moments. It’s serious, then wacky, but the humor comes at the right times. This is how I want people to hear the songs.

You also incorporated very traditional country instruments—banjo, fiddle, mandolin, pedal steel and so on—but not in a traditional way.

The goal with this album was to step outside the comfort zone with those instruments. I wonder what my grandpa would think of this record, especially when LL Cool J comes in or when Mat Kearney starts rapping in the middle of what feels like a Waylon tune. I’m a big fan of a lot of music that doesn’t use instruments like banjo, mandolin or pedal steel. I love the Killers, Coldplay and A Silent Film, even though I miss hearing guitar solos in their music. I love Muse. I love the sense of melodic abandon in all of those bands. Even though those bands don’t use traditional country instruments, that doesn’t mean that I couldn’t imitate some of that.

How did you personally step outside your comfort zone?

I’ve never produced before, so that was a little nerve wracking at first. It’s one thing to say I’m going to produce a record and then attempt to duplicate what I’ve always done when I worked with my buddy Frank Rogers on every other album of mine. The whole point of me producing this record was to do something different than what Frank does. Good or bad, it was going to be different. I wasn’t going to do what I’m used to doing, and I also wasn’t going to do what I’ve watched someone else do very well. I had to do it in a way I’ve never seen somebody else do. That was an eye opener. I didn’t know the first thing about Pro Tools when I started working on the record, but now I can’t get my hands off of it. A lot of the plug-ins that you hear on the record were all my ideas. It was fun to learn how to do that by necessity. All of us had to step up. We had never been left alone to do what we wanted to do before. For me as a guitar player, I wanted to make an album where the guitar was a large part of it, but I didn’t want this to be my “guitar” album.

You had already done that with Play, anyway.

That’s right. I didn’t want to worry about how I was going to make the guitar fit in. I wanted this to be a band in a house. I’m just one of seven players in the band. Now, guitar does get first dibs when it comes to a solo, because I’m going to be the one presenting it when we play onstage. But when it’s better for a fiddle or steel to say something in the song, I wanted to make sure that I didn’t overlook that. There’s a temptation when you’re your own producer and also a lead guitar player, but the next thing you know, every song is guitar oriented, and that only appeals to people like you and me.

There’s a lot of great feedback squall from delay effects on “I Can’t Change the World,” which is something most producers hate.

This producer doesn’t hate that. I played my black ’57 Strat and 1938 Martin D-28 on that, but the feedback parts were done with a steel guitar and an electric mandolin. There were actually two tracks of steel on that song. One is playing a melodic lead line and the other is all noise. There is no actual guitar feeding back on that song. What sounds like a synth underneath everything is a banjo through the SoundToys Crystallizer plug-in set to infinite repeats. That was an accident. I never heard anything like that before, so I decided to keep it.

There are also no background vocals on that song. Instead, I used the SoundToys EchoBoy plug-in for Pro Tools, which became the secondary vocalist. When I first recorded the song, I didn’t have the verses written yet. What’s great about having your own studio is you can cut something before you’re sure what it’s going to be. Initially, I cut a first verse and a chorus, but I wasn’t sure what the second chorus and bridge were going to be yet; I just left room for a solo and a bridge. I slapped that delay on the chorus the first time that I heard it, because I wanted to go from intimate to large. The delay effect became as much a part of the song as any instrument, and I didn’t change the delay at all after that. It stayed exactly the same from then through the mixing. It was magic.

On the instrumental track with the name written in Japanese characters (“幽 女”) that I have no idea how to pronounce, each instrument plays only a few bars before the next instrument takes over.

We’re never going to write the name in English. It’s always going to be Japanese. There are various translations of that—if you Google it you’ll find a bunch of different things—but I don’t want people to know exactly what those characters mean, although in Japan they know what that is. It’s basically this mythological figure that the Japanese have written folklore about, this woman who seeks revenge as a ghost on the man who did her wrong. I had heard about her, so I decided to do a song about her.

I wanted the main melody to sound Japanese or Asian, but it also had to lead into “Karate” and set it up. I couldn’t come out of a song like “I Can’t Change the World” and then go directly into “Karate.” I had to set the stage for something wacky. I also wanted the instrumental to be less than two minutes long. I didn’t want four minutes of us being overindulgent and just wailing. We each play a little. There are all kinds of things in there—even a fiddle played through a Trainwreck amp. Gary Hooker played the tic-tac six-string bass part. It’s fun to play something that short. Just when it gets to the point where the listener who is not you or me has had enough of the shotgun blast in the face with instruments being nuts, it’s time for another song.

You had a lot of equipment destroyed in the flood that hit Nashville in 2010. What new gear discoveries have you made?

This was the first album I’ve made since the flood. The 1957 Fender Electric Mandolin became my go-to instrument when I was looking for a unique sound. That through the Trainwreck Liverpool and Catalinbread Montavillian Echo was bizarre. It was like The Edge with twang. I played more Strat than I usually do. The black ’57 Strat, which is a hardtail, is on several songs. On “Those Crazy Christians” I used my blue Strat, which has a whammy bar, to get a Jeff Beck vibe on the song. My 1960 Gibson ES-330 is on a lot of songs, including the lead on “Death of a Single Man.” Most of the time it’s in the background, but I also used it through my Trainwreck Rocket for the solo on “Tin Can on a String” and for the blues solo on “Accidental Racist.” I love its P90 pickups, which are more me than the humbuckers on an ES-335. I used the Tele more for things where I needed my typical guitar voice that people are used to. One new thing I attempted to do was playing slide, which I’ve never done on a record before. I can’t wait for some kid in Nebraska to figure out what I did on “Beat This Summer.”

Did you use the G-bender with the slide?

That’s it. I played some slide on “The Mona Lisa” as well.

Most guitarists use B-benders. Why do you prefer the G-bender?

Because most guitarists are already using B-benders. [Diamond Rio guitarist] Jimmy Olander was probably my biggest influence on that. He has both, but he uses the G-bender more than the B-bender. I asked him about that when I first met him, and he recommended that I get the G-bender. He said it just sounds more natural.

It definitely works better if you want to sound like an actual pedal steel.

I agree. A B-bender has a very distinctive sound that is awesome, but it says B-bender guitar the minute I hear one. Most of my live guitars have G-benders in them. I don’t know whether a G-bender allows you to do a whole lot more than what you can already do with your finger, but it’s neat to use it when you’re out of ideas. That’s why I used it with the slide on “Beat This Summer,” which feels like a song by the Eagles. I thought, What would Don Felder do? What would be my version of that? You can’t really tell what I’m doing on the record, but I know that as soon as I play it on television that kids will be ordering their slides and G-benders.

The album has a lot of humorous moments, but it’s balanced out by some very serious moments as well, sometimes within the same song like “Those Crazy Christians,” where you talk about Christians going to Applebee’s at the end of one verse, but at the start of the next verse they’re going to Haiti.

That was another genre-bending moment for me. It feels like a contemporary song. It has a drum loop that we built using one mic on the drums and crushing the hell out of it. Then he plays over the top of it. The piano has a life of its own. Kendal [Marcy] was just playing away, and I put the EchoBoy plug in on it, which completely changed the part. It’s like when you put a delay on your guitar. The notes started to sing. Then I played those Jeff Beck whammy bar parts on the Strat through the Trainwreck Liverpool.

The lyrics are from the point of view of a guy who is baffled by why these people do these things—both extremely good and extremely puzzling. My wife just got back from Haiti, and I’m going this weekend, and it’s hard to fathom why someone would leave their comfortable existence to go there and help people find clean water and do mission work. The guy in the song isn’t really likable, and he sounds confused. I’m playing a character when I sing that. We all have our skeptical sides, but I’m not the guy waking up cranky on a Sunday morning. I’m only cranky on Sunday if NASCAR isn’t on. I consider that the gospel song on this album. I’ve cut gospel songs before, like “How Great Thou Art” and “In the Garden” but I think that “Those Crazy Christians” makes an even better case. I’ve had an agnostic friend sit on that couch and crack up and say, That is my song, and I’ve had two missionary friends who sit there and stand up at the end and say, That is my song. That’s the best feeling in the world. I’m a big Mark Twain fan. One of my favorite quotes from his is, “If Jesus Christ were alive today, one of the things that he would not be is a Christian.” [laughs] It’s to fun to question things from a healthy perspective and make people explore.

The album covers a lot of ground, both musically and lyrically.

I looked at the various stages that most of us will go through in life, especially when it comes to relationships. There’s a life-and-death metaphor that plays out throughout the entire record. You have everything from “I Can’t Change the World,” where you feel like you can’t control the larger things in life, to “Harvey Bodine” and “Death of a Single Man.” In “Tin Can on a String,” you can hear an actual human heartbeat. It’s like that moment where something hits you so heavily that the only thing you can hear is your heart. Then there’s “Officially Alive” which asks what does it actually mean to live? You’ve got the debate on when does life begin. Is it at conception? In my opinion it happens the first time your heart gets broken. [laughs]

But seriously, when are you really alive? Is it when you’re playing it safe or when you’re not? I feel like it’s when you are so deeply in love with someone or something. It can be the minute when you discover the guitar. For me, my life began at eight. My life as I know it began on a Christmas morning when my grandfather said, “I want you to have this,” and he gave me his old Silvertone guitar. Fast forward from that moment through the girl that I married, the house that I live in, the farmhouse studio we’re in right now, the friends that I associate with. Every one of those people and things are products of that one moment. My life began when I got my first guitar.

Chris is the co-author of Eruption - Conversations with Eddie Van Halen. He is a 40-year music industry veteran who started at Boardwalk Entertainment (Joan Jett, Night Ranger) and Roland US before becoming a guitar journalist in 1991. He has interviewed more than 600 artists, written more than 1,400 product reviews and contributed to Jeff Beck’s Beck 01: Hot Rods and Rock & Roll and Eric Clapton’s Six String Stories.

“I use a spark plug to play slide. It's a trick Lowell George showed me. It gets incredible sustain – metal on metal”: In the face of sexist skepticism, Fanny's June Millington carved a unique six-string path, and inspired countless players in the process

“There’d been three-minute solos, which were just ridiculous – and knackering to play live!” Stoner-doom merchants Sergeant Thunderhoof may have toned down the self-indulgence, but their 10-minute epics still get medieval on your eardrums

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)