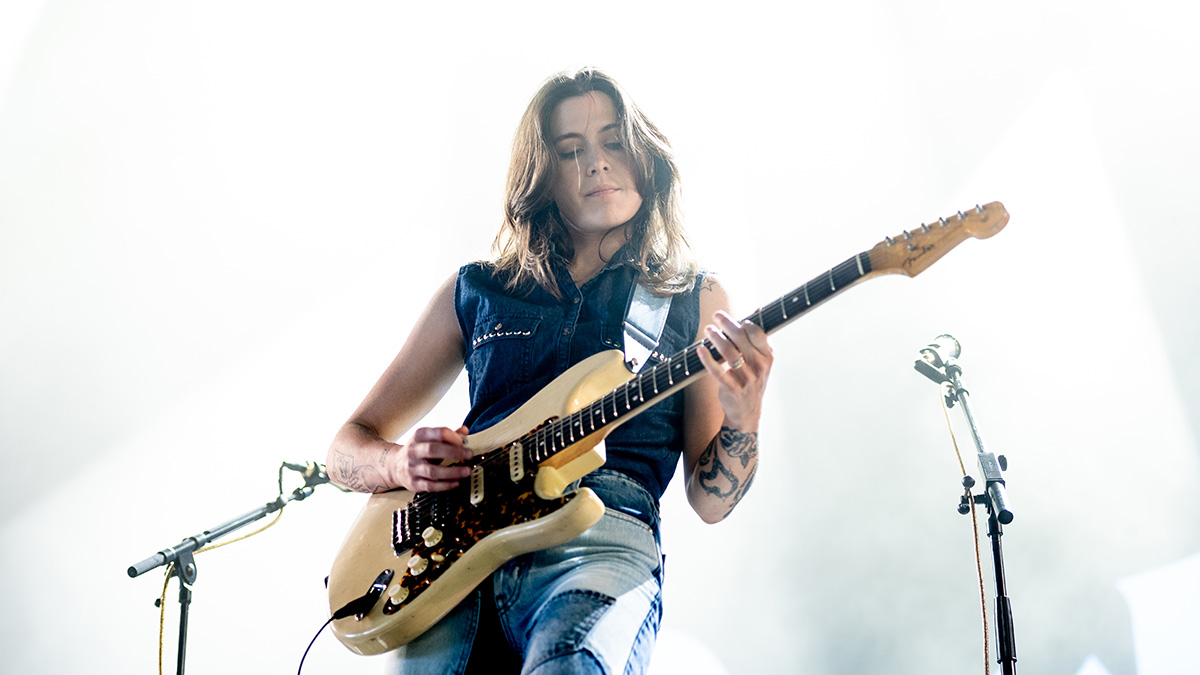

Doyle Bramhall II is speeding up the metabolism of his solo career. Fifteen years passed between his third and fourth solo albums, 2001’s Welcome and 2016’s Rich Man. Now, only two years later, Bramhall is back with Shades, an album that embraces a wide range of styles over the course of its 12 tracks, most of it centered around his stinging guitar leads and deep vocals.

“All of the bands I grew up loving — Jimi Hendrix, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Sly Stone, Eric Clapton, the Beatles — were so prolific,” Bramhall says. ”They’d tour constantly and somehow find a way to put out an album — or even two — per year. With this new album I wanted to get more into the flow of touring and putting out records consistently.”

It’s not like Bramhall was slacking during the long stretches between releases. He was fronting his own band and also working as a studio musician and/or sideman with the likes of Roger Waters, Gregg Allman, J.J. Cale, Elton John and Leon Russell. Most importantly, he’s been Eric Clapton’s valued collaborator and trusty guitar sidekick for most of the last decade, touring, recording, writing and even producing with Slowhand. He’s also written songs and produced music for Sheryl Crow and the Tedeschi Trucks Band, becoming a key member of the latter’s creative core.

Long before any of that, Bramhall was a fixture of the blues and blues rock world, born into the center of Austin’s nascent blues scene. His namesake father, who died in 2011, was Stevie Ray Vaughan’s best friend, occasional drummer, vocal inspiration and songwriting partner. Jimmie Vaughan was like an uncle to Bramhall II, and his professional performing career was launched when he joined Jimmie’s Fabulous Thunderbirds as an 18-year-old second guitarist.

Stevie Ray’s 1990 death sent Bramhall II spiraling into a dark place. “I had gotten sober and Stevie was very involved in that and in my continued sobriety,” says Bramhall. “When he died, I got very nihilistic.” Bramhall’s struggles continued through the formation, birth and early success of the Arc Angels, featuring him and Charlie Sexton fronting Vaughan’s Double Trouble rhythm section of Chris Layton and Tommy Shannon. The group broke up in 1993, and over the past 25 years, Bramhall II worked his way back into being a central figure in American roots and blues music.

On Shades, he sounds fully comfortable with himself. An array of special guests adds seasoning and variety while augmenting the strength of Bramhall’s songwriting. Clapton’s guitar lights up the slow-burning “Everything You Need,” while he duets with Norah Jones on the ballad “Searching for Love” and trades licks with Derek Trucks, backed by the Tedeschi Trucks Band, on Bob Dylan’s “Going, Going, Gone,” which he turns into a plaintive soul song.

“I wrote almost all of the material on Shades specifically for the album, and as I got into it, it seemed I was writing a lot of different styles of music,” Bramhall says. “That wasn’t a conscious decision but rather just that the songs that were coming out of me crossed different genres, and I’ve gotten better at going with the flow and following the music where it wants to lead me.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You’ve spent a lot of time, as a guitarist, backing other artists. Does that experience alter the way you approach your own music?

I try to always stay as open to learning as I can and to keep growing creatively. I think I learn the most when I’m in a supportive role, able to observe and be a good listener and accompanist. I’ve always been a good counter-puncher. Also, I’ve had the good fortune of playing with a lot of very gifted musicians and artists — even ones that were my idols growing up.

That started in Austin. Can you describe the musical impact Stevie Ray and Jimmie Vaughan had on you?

Jimmie and Stevie both impacted me in so many ways that shaped me as the guitar player and person I am today. They were my first and biggest influences — other than my father. Stevie always cared so much about what I was up to as a musician and about championing me. He would always ask me to show him my music and any songs I had written. He gave me the confidence to believe in myself and my music. He liked to get me on stage and say my name as often as possible, which was part of him taking me under the wings, and he suggested me to Jimmie as a second guitarist for the Fabulous Thunderbirds, which kicked off my touring career.

You grew up in the center of an incredible music scene. Did it always feel like a given that you’d be a musician?

No. Even though I was very musical from an early age and could play different instruments, I didn’t think seriously about being a musician until I was 14. Once I picked up the guitar there wasn’t a question in my mind. Music was it for me. Besides, I was sucking at algebra.

How much did you and your father play together?

When I was young we did a lot of playing and recording together. He would book sessions at studios for me when I was first starting out. I loved all the same music he loved and all the music he made. He was my favorite drummer and singer when I was growing up. I watched him play a million shows and sometimes he would take me on the road with him.

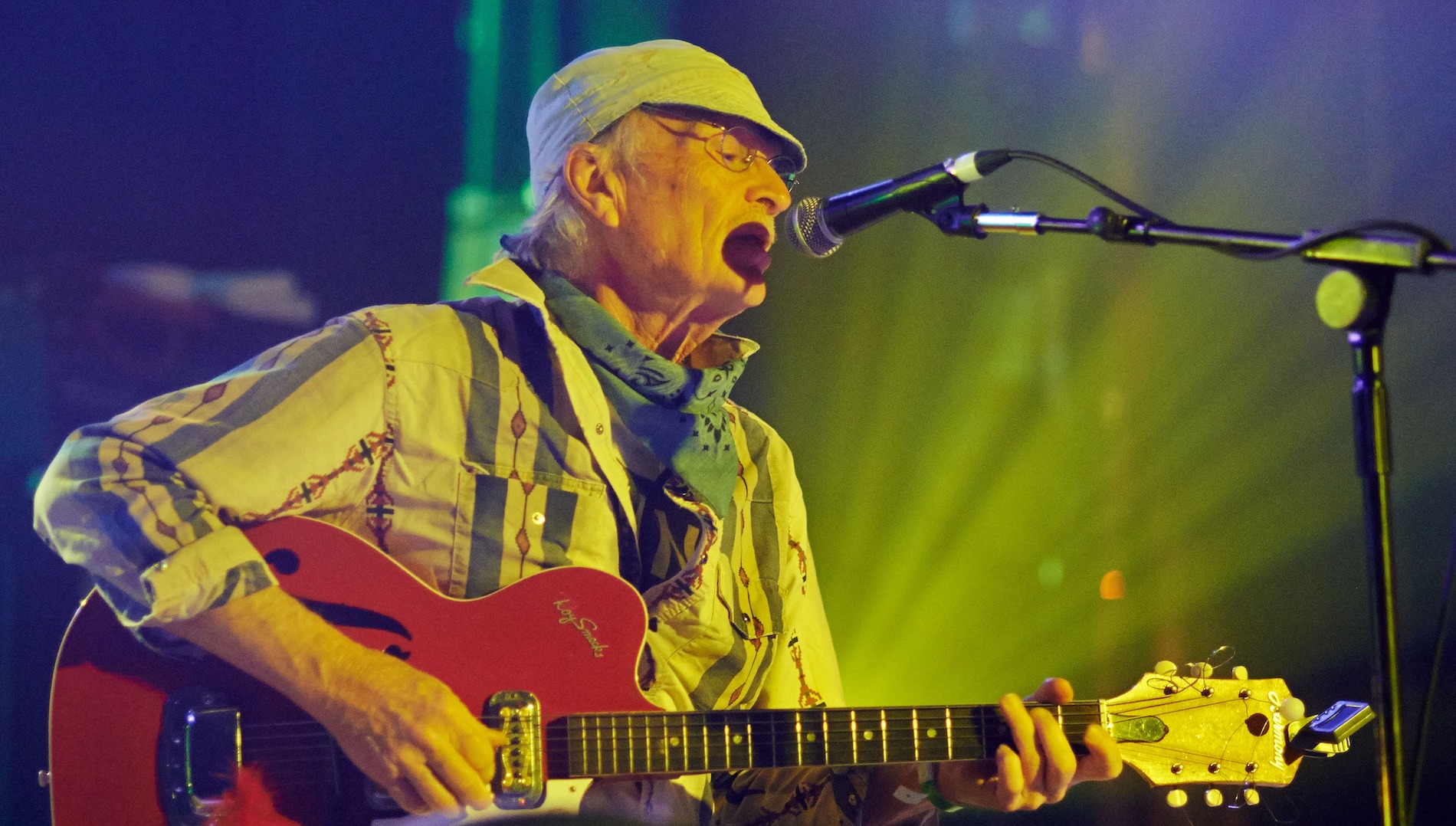

You’re back in Eric Clapton’s band for the limited shows he’s playing this year. How do you feel your time with Eric has influenced your own work?

I think just being in Eric’s presence a lot and watching how he’s very comfortable in his own skin — and always has been, as a performer, singer, guitar player and artist — has rubbed off on me and given me a sort of confidence. Just being near it is very powerful. He’s always known who he is, and he always values what I do, and my ideas, and encourages me as a solo artist and says he respects me as a songwriter. All of that has just given me faith in myself. I’ve always been introverted as a performer — unable to just let myself go and be unedited. I would always have to edit myself in some way, or try and be something, rather than just being in the moment with the music and feeling comfortable with it. It’s been hard to be okay with a bunch of people in the audience looking at me playing, but all of that has become easier and more natural from time spent with Eric and getting his approval. It’s really huge and hard to explain more precisely.

He plays on “Everything You Need.” Once Eric agreed to play on a song on your album, how did you decide this is the one it should be?

I just thought Eric would really like that song, knowing his taste and the things he’s into. I thought it might catch his attention. And it’s always nice to have somebody that is a guest on a song that you think they might relate to or enjoy rather than just getting them on something they have no connection to at all. It was just a guess that he would like the track, and he did. Then he was in the U.S., and I just drove out to where he was recording and spent the day with him. The track wasn’t even finished. I didn’t have lyrics for it. I just had the basic tracks: drums, bass and couple of guitars. Then I sang a melodic vocal idea, just so he’d know where to play, and all the gaps between that he could play in. And bam he played it, and it sounded great.

The Tedeschi Trucks Band play on the Bob Dylan song “Going, Going, Gone,” which Gregg Allman brought out of obscurity by including on his last album, 2017’s Southern Blood. What was it about that song that was attractive, and what made it seem like the right one to do with TTB?

I really had this shift in my life about seven years ago and ever since then I’ve been able to sort of trust what the universe puts in front of me, trust that if I go with something, one experience can then guide me to the next. I love that about music, and about life in general. The most magical experiences I’ve had in my life, musically and personally, have all come out of not knowing what was gonna happen and just putting myself out there and letting it be okay, even though uncharted territory can sometimes be a scary place.

And that’s what happened with “Going, Going, Gone” — one experience leading to the next. Gregg’s guitarist, Scott Sharrard, was putting together a tribute show to Gregg and the Allman Brothers Band and he asked me to do “Stormy Monday” and “Going, Going, Gone.” I don’t think I had ever played “Stormy Monday” beyond probably jamming along with the Bobby Bland version in my room when I was a kid, because every time somebody would pull it out at a blues gig I would usually leave, because it had just been done so much, and felt like a very stock thing to play. It didn’t feel unique enough, but we rehearsed and it felt great and when we did the songs live I really felt both of them and I just thought “Going, Going, Gone” had something special, an innate spirit to it, especially because Gregg recorded it right before he died. How heavy. And I played on one of Gregg’s albums (2011’s Low Country Blues) and was friends with him, and I really felt that.

And how and why did Tedeschi Trucks Band end up backing you on it?

While I was singing it live I was thinking about how it had a “Derek and Susan” quality to it, and in that very moment I thought, “Wow, it’d be great if I put this on my record with them backing me.” So I just called them and asked if I could come down and record the song with them. I was already working down there in their home studio quite a bit, doing overdubs for my album with their engineer Bobby Tis, and they generously agreed to play on that song. And it was basically a few takes and done. It was all live.

And they’ve started playing it now, which is amazing. It was a pretty obscure Dylan song nobody really knew, which made perfect sense for Gregg’s farewell album, which sort of put it back into the world.

Yeah. We should release it on both my record and TTB’s! Dylan songs are often like that, where there’s always a spirit, no matter who does it or how you do it. It always has this special life to it. It’s pretty incredible. When I was listening to the Gregg album, that song came on and I was like, “Wow, that’s such a great song. Who wrote it?” I looked it up and it’s like, “Bob Dylan, of course!” Man, Bob always wins.

You’ve done a lot of writing, producing, and performing with Derek and Susan. Can you discuss your relationship and collaborations a bit?

Spending time and making music with Derek and Susan is one of my greatest joys in life. It is really a gift to be able to make music with the people I love the most. I think our friendship spills into our collaborations and we make music from the purest place. Derek and Susan treat all the musicians they work with like family. There really isn’t a more nurturing environment for making music than theirs — and simply put, they are bad asses!

A simple question I’ve always wondered about: How did you come to play a right-handed guitar upside down? It’s common with older musicians but pretty unusual for someone our age. You could have gotten a lefty guitar!

It just felt comfortable to hold a righty guitar left handed and it never occurred to me to change the strings. I didn’t even know about that when I started out. It wasn’t until I went to take a proper lesson from a guitar teacher that I was told that I needed to string the guitar left handed or play right handed to be taught. I had already learned 100 songs or so that way and it sounded good to me so I walked out and never looked back!

Alan Paul is the author of three books, Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan, One Way Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as Managing Editor from 1991-96. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort.