The Doors: Blues Travelers

When their psychedelic-rock excursion finally ran out of gas, the Doors got their music back on track with the blues-influenced Morrison Hotel. On the 40th anniversary of the classic rock milestone, guitarist Robby Krieger tells the story behind its creation.

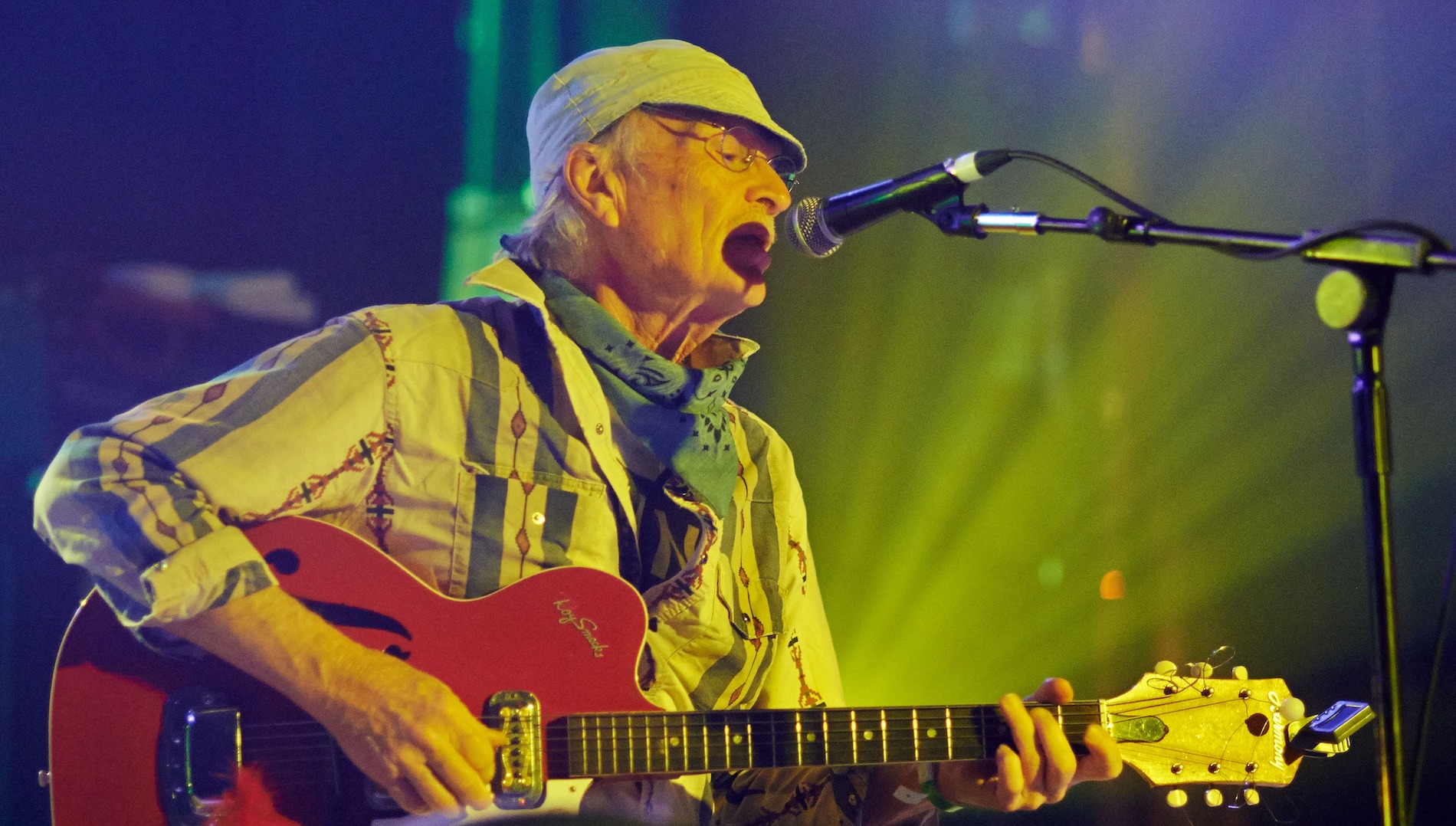

Robby Krieger had already made four albums with the Doors by the time the group got together in November 1969 to cut Morrison Hotel. Over the course of those earlier records, Krieger had demonstrated his talent for flamenco-style guitarwork, exotic leads and avant-garde psychedelic-rock workouts. But he’d never really had a chance to properly show off his blues chops as so many other electric guitar greats of the period had. That changed with Morrison Hotel.

“I never even considered myself a rocking guitar player,” says Krieger, who had been playing electric guitar for only six months when he joined singer Jim Morrison, keyboardist Ray Manzarek and drummer John Densmore to form the Doors, in 1965. He’d started out as an acoustic player. “I first learned flamenco and then a lot of folk and folk blues,” Krieger says. “That’s why I played with my fingers and just adapted it to what we were doing. I really learned to play as a member of the Doors. I just tried to sound like myself and play something that would complement Jim’s singing.”

With Morrison Hotel, though, Krieger came into his own. Not only is the guitar more to the fore than on previous Doors releases but he attacks his solos with newfound intensity on tracks like “Roadhouse Blues” and “Land Ho!” The album was transformative both for Krieger and for the Doors. With it, the San Francisco–based psychedelic rock group recast itself as a down-and-dirty blues-rock quartet.

Emerging from San Francisco’s vibrant psychedelic rock scene in 1966, the Doors had quickly become one of the biggest-selling practitioners of the genre, with hits like “Light My Fire,” “Hello, I Love You” and “People Are Strange.” Krieger’s sinewy guitar playing, Manzarek’s classical-influenced electronic organ and harpsichord work, and Densmore’s jazzy drumming provided a trippy and exotic musical bed onto which Morrison could lay his sonorous vocals and work his shamanistic persona. The resulting sound was fresh and wholly original.

But by the time they released 1969’s The Soft Parade, the Doors were clearly running out of ideas. Though the album downplayed the group’s stronger psychedelic tendencies, the four-part title track was a rambling journey through disparate musical styles, and the brass and string arrangements throughout the album did little to lift what was—with the exception of the radio hit “Touch Me”— mostly weak material. Moreover, the album’s progressive musical pretensions were hopelessly out of date at a time when acts like Jimi Hendrix, the Rolling Stones and the newly formed Led Zeppelin were cutting a path back to blues-based music.

It was clear that the Doors needed to find a new direction. They did it by stripping away their sonic excesses and indulging themselves in blues-based rock. The result was an album that blew away all expectations: Morrison Hotel. “Roadhouse Blues,” the album’s raunchy, harmonica-driven opening track, sets the tone for what follows, as the group works its way through funk workouts like “Peace Frog” and the driving blues rock of “Queen of the Highway.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Whereas Manzarek had traditionally handled bass duties in the past with a keyboard bass, for Morrison Hotel the Doors decided to work with a real bassist to give the music a truer blues feel. To that end, they recruited blues-rock guitarist Lonnie Mack, who had a hit with the instrumental “Wham!” in 1963, to play bass on “Roadhouse Blues” and “Maggie M’Gill,” while Ray Neapolitan handled bass for “Peace Frog” and “Ship of Fools.” In addition, the Lovin’ Spoonful’s John Sebastian contributed harmonica work under the alias of G. Puglese on “Roadhouse Blues.”

Released in February 1970, Morrison Hotel reestablished the Doors as a vital group for their times. Even though the album generated no singles, it sold well, reaching Number Four in the U.S. The album also proved to be a crucial setup for the Doors’ next album (and last with Jim Morrison), L.A. Woman, on which they would dig even deeper into the blues, with more commercially successful results.

Krieger has spent the ensuing decades working at his craft, something that is abundantly clear on his new solo CD, Singularity, where he displays sharpened flamenco licks and a technically adept, jazz-fusion virtuosity. His expanded repertoire of techniques is also on display in his continuing work with Manzarek. The two have been playing together regularly since 2001, when they reformed as the Doors of the 21st Century. A subsequent lawsuit by Densmore forced them to drop the use of the Doors name, but they continue to perform as Manzarek-Krieger.

By any name, the music of the Doors remains relevant decades after it was recorded. Krieger believes that is especially true of Morrison Hotel. “I feel like Morrison Hotel has really stood the test of time,” he says. “For us, it was going back to basics and just having fun. And I think you can still hear that 40 years later.”

GUITAR WORLDMorrison Hotel represented a back-to-basics approach for the Doors after all the orchestrations of The Soft Parade. It seems that a lot of bands were doing similar things in 1970. Was there something in the air?

KRIEGER I think what happened is the Beatles had done Sgt. Pepper’s in 1967, and everybody felt like they had to do that, too. Then everyone said, “What are we doing? Let’s get back to basics.” That’s certainly how we felt, and I really feel like that was the feeling in the air. That’s what caused so many of us to become more grandiose and experimental between 1967 and 1969, and afterward to scale back and go back to our roots.

GW The standout track on Morrison Hotel is “Roadhouse Blues.” Were the blues the “roots” you’re referring to?

KRIEGER Yeah, I loved the blues, and so did Jim, who was really getting deeply into it at that point. He was also going down to the Whisky [A Go Go] or the Troubadour and jumping onstage with whoever was performing. He just loved Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters. So did I, but what pissed me off is Jim would never bother to learn all the words from the blues songs. He’d do one verse, then go off and do his own stuff, which sometimes was better. But that could also be really frustrating.

GW Was everyone in the band on the same page when it came to the blues?

KRIEGER No! John hated playing the blues. [laughs] Being the drummer or bass player in a blues band can be boring, because you have to play the same thing over and over. John wanted to play some things that were not just a regular blues, so a lot of our blues had something different going on. And I loved the way he played the blues.

GW In a way, his dislike of playing the blues made you a better blues band.

KRIEGER Exactly. [laughs] That is true even on “Roadhouse,” which is as basic as you can get. What John plays there is really cool. It’s a total two-beat backbeat thing, which is especially evident on the chorus. It’s the type of thing that you don’t hear anymore, but which John picked up from listening to some real old blues. It’s the kind of little, subtle thing that has gotten lost, and it was so old even then that it sounded new.

GW I would contend that more than John’s drumming makes “Roadhouse Blues” a standout track.

KRIEGER [laughs] Oh yeah. It is one of my personal favorites. I was always proud of that song, because as simple as it is, it’s not just another blues. That one little lick makes it a song, and I think that sums up the genius of the Doors. I think that song stands up really well as an example of what made us a great band. And the session was really cool—one of my fondest memories of the band. We cut the tune live, with John Sebastian playing harp and Lonnie Mack playing bass. He came up with that fantastic bass line.

GW Mack was a guitar legend. How did he come to play bass for the Doors?

KRIEGER He was working in the studio after quitting the music business to sell bibles. Someone found out and told him to go to Elektra and ask for a job. I loved his stuff and was amazed that he had quit playing and tickled that he was around, so it was a natural to ask him to play on something. He was a nice guy. He always used to get mad because I would call him a “bass player,” and he would say, “I’m not a bass player. I’m a gee-tar player.”

GW For the fourth disc of The Doors: Box Set [1997], you, Ray and John chose your five favorite songs. One of your selections was Morrison Hotel’s “Peace Frog.” What makes that song so special for you?

KRIEGER I had written the music to that without any lyrics. I was trying to cop a James Brown feel. I kind of messed up on it, but it came out sounding really cool. I wrote the music, including those breaks, in their most basic forms, and then it was given the Doors treatment by the three of us and Ray Neapolitan, who was playing bass. Jim couldn’t figure out words for it, and I didn’t have any, so we just cut it as an instrumental track. Later, he got out his notebook and he and [producer] Paul Rothchild found this poem called “Abortion Story,” which had all the stuff about blood in the streets. Then the two of them came up with a vocal line to fit the music. That was extremely unusual, because usually we wouldn’t record something until he knew what he was going to sing on it. And the lyrics usually came with the music, not in two separate packages. I actually always thought the fit here was a little uncomfortable, but it’s still one my favorites.

GW Your solo on there has a really cool and very different sound. What were you playing through?

KRIEGER It was a Fender Twin Reverb played real loud, and the echo was done with tape delay.

GW The album took its name from a real hotel in L.A. There is also the famous picture on the album of the Doors hanging out at the Hard Rock Cafe [a Los Angeles bar from which the popular restaurant chain later took its name]. How did you find these places?

KRIEGER Ray found the hotel, which was a skid-row flophouse, while driving around downtown Los Angeles. It seemed a natural place to do a photo shoot, given its name, so we went there with [photographer] Henry Diltz. We were already recording the album, and once we took that picture, the album had a name. While we were there doing the shoot, someone in the group stumbled onto the Hard Rock Cafe, a wino bar. We stopped in to have a beer and take some more pictures. Those places were both in the heart of wino country.

Jim loved it down there. He loved talking to those guys. There was one guy who claimed that if you gave him 50 cents, he could whistle louder than anything you’ve ever heard because Jesus would whistle through him. And it was incredibly loud.

GW By the time you cut Morrison Hotel, Jim had already been arrested in Miami and was facing obscenity charges and possible jail time [over the Doors’ controversial performance at the Dinner Key Auditorium in Miami, on March 1, 1969]. Did you all feel worried and desperate about the future of the band?

KRIEGER No more worried and desperate than on the other albums. [laughs] We were always kind of on edge. We couldn’t get gigs anywhere and had just come off The Soft Parade, where everyone had knocked us for overproducing—and some of us kind of agreed with the criticism. So I think we were just having fun getting back to the basics and playing music together. And when it came out and got great press, that felt great.

GW You obviously have a real fondness for John’s drumming and a tremendous history together. Has it been hard to be split up by a lawsuit?

KRIEGER Yes, it is difficult. I think John kind of painted himself into a corner. He said he didn’t want to play with anyone unless Eddie Vedder was singing. We want John to play, and I know the fans want him to play and… It’s just frustrating. There are a lot of issues that need to be worked out there. This happens with a lot of groups, where one guy doesn’t want to play and the others want to use the band’s name, and it ends up in court, which is really stupid. The only thing that happens is the lawyers make a lot of money.

GW So where does it stand now? Can you pick up the phone and call him and discuss other things, or is it too far gone?

KRIEGER It’s tough, man. It’s really tough. I really believe that we’ll get back together at some point, but we haven’t actually talked since the lawsuit was filed, to be honest. We send emails and stuff, and we do get together for Doors business. It could have been worse, because we can still collaborate on business deals and Doors issues and keep some cool stuff coming out, which is good.

GW You’re still playing Doors material with Ray. Does it feel very different playing with him than any other keyboard player?

KRIEGER Yes, it does. I’ve had many different keyboard guys over the years, and it’s pretty tough to find the right guy to play Doors music. It’s just as tough for me as finding the right singer. I want them to play the right notes when we play Doors songs, but it’s impossible to duplicate Ray’s sound.

GW I don’t believe it’s as hard as finding a singer who can nail Jim Morrison without going over the top. Have you had trouble with guys who think they need to behave like Jim—drinking to excess, being unreliable and so on?

KRIEGER Oh, yeah. And, you know, we already lived through that once, and the last thing we want is to deal with it again. It’s true that finding a singer to sing Doors songs is probably the toughest thing. And our fans can be picky in unpredictable ways. We were working with [the Cult’s] Ian Astbury, who kind of looked like Jim and tried to act like Jim. He had a great voice, which wasn’t really like Jim’s voice, but it worked because he brought his own thing to it. I thought it sounded great, but a lot of people didn’t like that he tried to look like Jim. You can’t please everyone, but when Ian went back to play with the Cult, we had Brett Scallions from Fuel come in. He looked nothing like Jim and acted nothing like him. But he sounded good, and we got fewer complaints.

Now we have Miljenko Matijević, who came from Steelheart. The guy doesn’t look like Jim or try to act like him in any way. His stage thing is more metal, I guess. But he nails the vocals incredibly well—he has, like, a six-octave range—and so far we’ve had a great response. People really dig him. So we’re going to keep going out there and having fun with the music of the Doors.

“The main acoustic is a $100 Fender – the strings were super-old and dusty. We hate new strings!” Meet Great Grandpa, the unpredictable indie rockers making epic anthems with cheap acoustics – and recording guitars like a Queens of the Stone Age drummer

“You can almost hear the music in your head when looking at these photos”: How legendary photographer Jim Marshall captured the essence of the Grateful Dead and documented the rise of the ultimate jam band