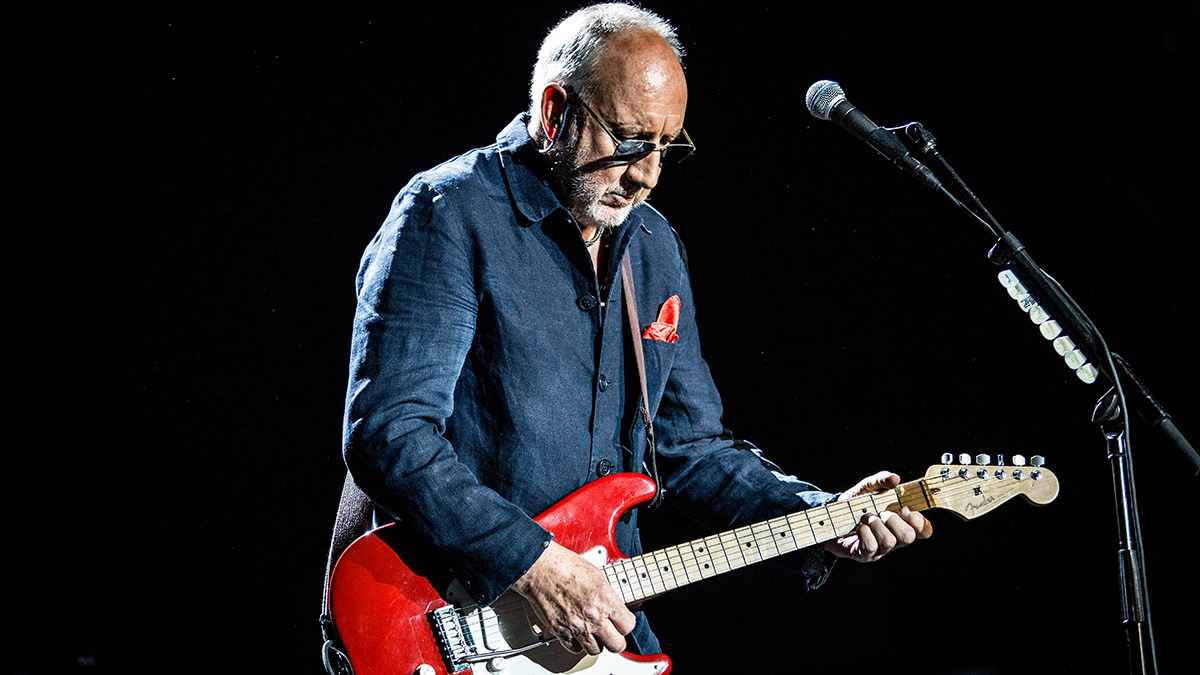

Deep Purple Bassist Roger Glover Talks Ritchie Blackmore, Playing with a Pick and Producing Judas Priest

He’s best known as the bass-playing rock of Deep Purple for nearly 50 years, and has produced albums for Judas Priest and others, but what Guitar World readers really want to know is…

The majority of bassists who came up during the seventies play with their fingers. why do you choose to play with a pick? —Jison Lee

When I pick up a bass and just mess around, I usually play with my fingers, but I’ve always played better with a pick. In terms of the high-speed accuracy, feel and attack needed to play Deep Purple’s music, I get more volume and power when I play with a pick. I’d never properly be able to play “Highway Star” with my fingers.

Ritchie Blackmore is known as being difficult to work with. Is this true, and how was your relationship with him during your years together in Deep Purple and Rainbow? —Kevin Majeski

Yes, he can be difficult to work with, but he is even more difficult to live with. Blackmore is a very unique character, and in the early days we had fantastic times and wrote great songs. He’s always been very edgy, cynical and did what he wanted. That can lead to problems, especially in a band situation. No one in Purple was in control—we were a band of five leaders—whereas Rainbow was his band, so he had the final say. I don’t want to emphasize Ritchie’s difficulties, because I’m proud as punch to have played with him.

What are your fondest memories of playing with [the late keyboardist] Jon Lord in Deep Purple? —Tom Kailua

How many do you want? We must’ve played a couple of thousand gigs, I suppose, and each was special. His lovely, uplifting personality came through when he played, and he never played to show off. Jon was one of the few keyboardists who could take his fingers off the keyboard for a while. When he played a solo, he’d let the organ breathe in between phrases, like a sax player might.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jon played the blues when he was young, and that gave him a solid foundation, because when he played hard in Deep Purple, he was able to match Blackmore’s massive guitar sound and transform the organ from a polite instrument and stand toe-to-toe with a guitarist as overpowering as Blackmore. Jon started abusing his instrument and sticking it through a Marshall instead of a Leslie to make it scream. Jon invented a keyboard style that was unique onto itself. We called it “rhythm organ.” Blackmore wasn’t keen on playing rhythm guitar, so Jon took that role, which in turn allowed Ritchie to play freely.

Do you think the manner in which your bass and Ian Paice’s drums steadily anchored the groove, while Ritchie Blackmore and Jon Lord traded off solos, working in tandem with Ian Gillan’s savage screams, helped lay down the groundwork for heavy metal in 1970 with Deep Purple in Rock? —John Lavara

I think so. In Rock was a groundbreaking album, and very heavy. It was my first studio album with the band. Before Gillan and I joined, Purple was more known for rearranging other people’s songs. The album prior to In Rock, Concerto for Band and Orchestra [1969], was Jon Lord’s baby. People were confused about what kind of band we were. Subsequently, Blackmore firmly stepped up and changed the band’s identity into a jamming, hard rocking force. According to the press, Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple stand out as the holy triumvirate of heavy rock. It’s not quite as simple as that, but I’ve heard it so many times I tend to believe it.

Why did you leave Deep Purple following 1973’s Who Do We Think We Are? —Bob Smith

In 1972, during the album’s recording, the relationships between band members, in particular Blackmore and Ian Gillan, had broken down. Ritchie started flexing his muscles more than ever, which didn’t go down well with the rest of the group. It got to a point where Blackmore and Gillan didn’t even speak. Touring became an issue; they met only onstage. Before long, Gillan resigned from the band. At that point, it was rumored that Blackmore and Ian Paice were going to leave as well, and they were going to form a trio. Deep Purple was at the height of its success and veering on splitting up! It didn’t make sense. The next thing I know, nobody was talking to me, so I knew something was up. Our manager told me that Blackmore would stay in the band only on the condition that I leave—I don’t know why; you’d have to ask Ritchie that—so I left and Blackmore carried on with Purple for another two albums. Years later, we all reunited in 1984 for Perfect Strangers.

Deep Purple’s 1972 album, Made in Japan, is recognized worldwide as one of the greatest live albums ever. Why do you think that album is still so revered even to this day? —Jim Lowry

When it was recorded, the band was at its peak musically and commercially. We were basking in our success. The arrangements of those songs had evolved since they were originally recorded, so they sounded fresh. It’s a totally honest live album with no overdubs. It had a wild freedom of expression and was a special moment in time.

“Smoke on the Water” is one of the most popular songs from the Seventies. You’ve played that song many hundreds of times onstage. Are you sick of playing it? —Ray Ronson

I never tire of it. I don’t listen to the song, but rather experience the crowd’s enthusiastic reaction to it. It’s a very simple and fun song to play. It’s a skeletal structure, which enables me to play different bass parts every night. I stand in awe and watch the audience’s joy, whether it’s youngsters who have never seen us in concert, or our older fans who have seen us many times.

How is it different playing with Steve Morse in comparison to Ritchie Blackmore? —Steve Wagner

[Chuckling] Ritchie would never guide me along the way, whereas Steve is an excellent teacher. Steve has awesome technique and dexterity. When he first joined the band we recorded Purpendicular [1996], which was a new beginning for the band in much the same way In Rock was 26 years earlier. When Steve asks me to play a difficult part, he helps me find the proper fingering that would work, and before long I’m playing it with ease.

You’ve produced Deep Purple and Rainbow albums and many albums by other artists. How did you first get into producing? —Evan Lerner

I’ve had knowledge of the recording studio long before I joined Purple. The best thing about producing is getting a good performance from someone. The first album I produced was Rupert Hine’s Pick Up a Bone [1971]. While I was busy touring with Purple in the early Seventies, one of our opening acts was Nazareth, and they asked me to produce their album Raza-manaz [1973]. It became a hit, and I was blown away. And since I was no longer in Purple at the time, because of dysfunction and disruption, I decided to become a record producer.

Over the years you’ve played with great drummers such as Ian Paice, Cozy Powell and Bobby Rondinelli. What’s different about each of their styles? —Derick Lutz

Prior to working with Paice, I’ve never really thought much about drums other than if they kept good time and if they sounded good. Paice opened my eyes to drums; he plays with an unbelievably fluid finesse, which comes from his teenage years playing big-band music. His playing has a jazz swing to it, so when he plays rock, it has subtle undertones of swing. Very few drummers play like him; most play like a drum machine. One of the first sessions we had, in 1969, Paice told me, “I don’t follow—I lead.” That comment put me in my place. So over our many years together, I just learned to tuck in with him, and it works.

Cozy, on the other hand, was a hard hitter who was macho looking and macho playing. It’s not that he couldn’t play gently, because he could. He was a lot better drummer than people gave him credit for, and he was a showman. Rondinelli, meanwhile, grew up later, so he started listening to rock when it was already established. Like many drummers of his era, he plays well, but his style is not as distinctive as Paice’s or Cozy’s. I’ve also worked with Simon Phillips, who is phenomenal. He played on my second solo album, Elements [1978], and I worked with him in the studio on a few of the albums that I produced.

Your production work on Judas Priest’s Sin After Sin is superb—the guitars and drums leap through the mix. How did you come to produce that album? —Bud Ripley

That album was a salvage job. To make a long story short, their record company wanted a name producer; but when I went to the group’s rehearsals, I had an uneasy feeling and felt I wasn’t wanted. The band told me they wanted to produce it themselves, so I said, “Okay.” A few weeks go by, and [guitarist] Glenn Tipton invited me to come down to the studio. He told me they weren’t happy with the tracks they recorded, and that they sacked their drummer. Glenn told me they had a session drummer coming in, Simon Phillips, who happened to be a friend of mine. So I listened to the tracks and suggested they should start afresh, and we cranked out the album in six days.

Rumor has it that deep purple may be retiring soon. is that true? —Steve Devin

Soon does not specify a time. I already retired when I was 19, when I used to mow lawns. Making music for the past 50 years has been my retirement. It keeps you young when you are doing what you crave. I don’t plan on stopping anytime soon, whenever soon will be.

“I was playing stuff I don’t think James Brown understood. He told me, ‘You have to play the one – you’re playing too much’”: Six years after he quit touring, Bootsy Collins reflects on James Brown and George Clinton, and what he gets out of playing today

“When I first heard his voice in my headphones, there was that moment of, ‘My God! I’m recording with David Bowie!’” Bassist Tim Lefebvre on the making of David Bowie's Lazarus

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)