Chris Robinson and Neal Casal Talk New Brotherhood Album, 'Barefoot in the Head'

“The real inspiration for this band is what I think of as roots music—which is everything: jazz, bluegrass, rock and roll, funk/soul/R&B, pop, country, blues, Appalachian folk. As a band, we all love all of these different kinds of music, so why wouldn’t we be inspired by everything from the Stanley Brothers to Lee Stevens’ first solo album to Weather Report, and beyond?”

Chris Robinson is discussing the inner workings of the Chris Robinson Brotherhood, the group he assembled in 2011 following his departure from the Black Crowes.

Robinson has been extremely busy—and incredibly prolific—with this current venture, comprised of guitarist Neal Casal (Ryan Adams, Hard Working Americans, Circles Around the Sun), former Black Crowes keyboardist Adam Mac-Dougall (Macy Gray, Ben Taylor Band), bassist Jeff Hill (Larry Campbell and Teresa Williams, Rufus Wainwright, Trey Anastasio) and drummer Tony Leone (Ollabelle, Levon Helm, Phil Lesh and Friends).

Though Robinson had stated that his initial intention with the CRB was to “have a local L.A. band, just play in California, and see where the music takes us,” he very quickly embarked on an ambitious North American tour while releasing four albums between 2012 and 2014, Big Moon Ritual and The Magic Door (2012), the live Betty’s S.F. Blends, Volume One (2013) and Phosphorescent Harvest (2014).

He has since released a fourth studio album, Any Way You Love, We Know How You Feel and an EP, If You Lived Here, You’d Be Home Now (both 2016), followed by the band’s latest collection of new material, Barefoot in the Head. Combined with two more live Betty’s Blends releases and 2014’s Try Rock ’n’ Roll EP, that’s an astonishing 10 albums in five years.

“We have the freedom to invent this band’s mythology, on the run, coming at it from outside the box,” says Robinson. “The seedling hatched seven years ago and it has progressed in a purely natural way, which is great. I’ve been through it the other way around, way back in my youth, but that doesn’t take away from the amazing respect I have and the unique opportunities I had while in the Black Crowes.”

Barefoot in the Head traverses the broad terrain of sounds and influences that comprise Chris Robinson’s musical creativity, from the Sly Stone funk/soul of “Behold the Seer,” the Bob Dylan/the Band vibe of “She Shares My Blankets,” the Beatles-esque twists heard on “If You Had a Heart to Break” and the heavier T. Rex/Mott the Hoople rock-type grind on “Hark the Herald Hermit Speaks.” The true magic of the band is that they find a way to infuse all of these disparate elements in a seamless, organic way.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Chris and Neal took some time out to discuss the band’s latest expansive and musically ambitious release, Barefoot in the Head.

Chris, how did you and Neal initially connect, and what makes him someone you want to have in your band?

CHRIS ROBINSON I met Neal in the early Nineties in the East Village in New York City at Three of Cups, an Italian restaurant/rock and roll bar. A few years later, I took the Beachwood Sparks on tour with the Black Crowes and Neal was in that band at the time, and that’s where our friendship started. There was also a moment when Neal was going to join the Crowes but Marc Ford ended up coming back into the band.

NEAL CASAL We both frequented Three of Cups but we were in different scenes. Chris was at the height of rock stardom then, and I was in a different crowd. But I was a big fan of the band, and we got to know each other some. He was evangelical about turning people onto good music, overturning stones and discovering old, unknown records and musical gems. He turned me on to [Scottish folk guitarist] Bert Jansch, John Renbourne, Terry Reid and The Incredible String Band. Back in the early Nineties, it was rare to hear someone speak authoritatively about these musicians and bands. His tastes run wide and deep, as do mine.

ROBINSON From the beginning, I could see that Neal and I like the same stuff and have similar tastes. When I asked him to join this band seven years ago, it just so happened that he wasn’t committed to anything, so it was fortuitous. My whole thing is that I don’t need a guitar player—I need a writing partner. We have that threefold now because Adam is active compositionally, too. I’m into nurturing the group aspect of this too; if someone has a part that’s better than the one we’ve got right now, have at it! I love that about this band.

Chris, does your experience with the Black Crowes inform your new music in any way?

ROBINSON The Black Crowes—in my view now as a 50-year-old “folk singer”—is that it was something that happened to me. At the start of the Crowes, we didn’t have a big local scene in Atlanta to be a part of. Luckily for us, [record company executive/producer] George Drakoulias saw us, and you put your coin in the slot—DING DING DING!!!—it comes up cherries and boom the race is on. It was a rocket ride that was unique but also scary when you are a kid in this adult world with people with money symbols in their eyes. You’re trying to have this soulful connection to the energy that you think is “rock and roll,” that you believe in. I just see it as a dedication to the muse.

CASAL As long as the quality is high, we are free to go anywhere we want, which is the best place for a band to be. We’re a hard-working bunch, all of us, with the same mindset, which is “the time is now!”

ROBINSON We don’t have any hit records to live up to, there’s no one pushing us in any direction that is not completely our own, our own personal and emotional content, so the idea is to take full advantage of it.

It sounds like you are free to follow your creativity wherever it may take you.

ROBINSON There’s no one there with expectations, so we are free to create and play music that we like, and that interests and excites us.

CASAL There’s no evil record company guy standing in the corner of the control room, saying, “Hey guys, do you really want to be, like, going in that direction?”

ROBINSON That’s like when Dave Chappell adopts an average older white guy’s voice—no one likes that guy! [laughs] I don’t care where you are from, that guy is not cool!

Isn’t that funny? We have removed ourselves from all of that, truly. We’ve all made great sacrifices to have this freedom: we sleep on the tour bus, we play five nights a week, three hours a night, two-hour soundchecks, average 115 shows a year, we work hard and we’re still not in a place where we are jetting over to the south of France whenevwer we can. We have to be pragmatic and realistic in our business model, and that has to be representative of the same attitude.

When did all of the material come together for Barefoot in the Head?

ROBINSON Leading up to the last record, Any Way You Love…, and the EP, If You Lived Here…, we had been working really hard for three years and we hadn’t been in the studio, so we had more of a budget to work with, plus an extra 10 days. When we finished those sessions a year ago in January, I came home and we had a little time between runs, so I just kept writing. I was in a great headspace.

You know, these times are filled with anxiety, uncertainty and the great toxic illusion of fear and ignorance surrounds us. So you have to be able to withstand that, fight the fear and focus on the things you can control. That’s where it all coalesces. When other things are in chaos, the “poetry” should be focused and expressive. If you can!

When we started this band, we were at a club somewhere in Kansas and I was setting up my rig, taking my amps out of the cases, and a kid said to me, “Why are you doing that?” thinking that I should have someone doing it for me. The Black Crowes drove around in a van for years before we got to travel on buses, and on private airplanes, and stay in the nicest hotels around the globe. Why wouldn’t I do this? The music doesn’t care.

No matter what I’ve been through, right or wrong—if I should have said something, or if I shouldn’t have said something—those things don’t matter. The music business is a system, the rules of the shit, right? If you stop your dedication to the muse, to art, to this life…it’s an archetypal thing that’s not just about rock and roll or musicians. But if it does become just a job, or something that you “learned,” then it isn’t alive anymore. And if it’s not alive, why am I dealing with this dead stuff?

In my 12 years of playing with Dickey Betts, he has always demonstrated that there is only one way to play music, which is to give all of yourself to the moment of creativity, and as a band we will find where we are going, together.

ROBINSON Yes, “I will be revealed!” The mystery is revealed at that point. Dickey Betts is one of the greatest guitarists in rock history, but to maintain that open spirit… Playing music is kind of like entering some crystal-lined cavern, but for some people, after a while it’s just like entering any old living room. Some of us have the same reverence every time it reveals itself, and you discover new chambers. I see music like that. You have to have that same mindset whether you are in a set composition or you are improvising. You should always have the same awe and wonder and magic about it.

Can you point to any specific instances when this became apparent to you?

ROBINSON Absolutely. I remember when we were recording the fourth Black Crowes album, Three Snakes and a Charm, I had this song called “Halfway to Everywhere” that was conceptually like a Sly and the Family Stone-Temptations-Parliament/Funkadelic tune with three different singers doing three different parts. I had my great friends Garry Shider from Funkadelic and Mudbone Cooper.

We were standing at the mic—and I was pretty “far out” with these guys by that point in the day, trying my best to keep up with the Funkadelic crew even though I was running hard myself—and it dawned on me that I had never sung with other experienced guys or producers like these guys; I was thrust into this “do it!” mentality. We were at a home studio in Georgia, and when I was on the mic with these guys, I was thinking of having grown up listening to them with Parliament/Funkadelic, like Garry and his cousin Glen Goins, who were the guys I was imitating as a kid, trying to find my voice. Being next to them and seeing how animated and visceral these guys were, I realized, Oh—there should be nothing restraining you! You have to dive in fearlessly, and we are drawn to that because it fits who we are.

When did you get started on the songs for this new record?

ROBINSON By the end of last summer, I was contemplating moving back over the hill to Stinson Beach and making the record, and I said to the guys, “Listen, I don’t want any of our road gear in the studio—no amps or anything that we used before on any recordings. Bring whatever you want, but not the same amps, guitars and effects.” Any stringed instrument, every stringed instrument!

CASAL That’s what led me to picking up the banjo, and Jeff [Hill] plays beautiful upright bass, and Tony [Leone] added great mandolin playing, too. We started flexing our muscles as a unit, and what’s so strong about this record is the ensemble playing. That’s what you can get when you go straight into the studio after an entire year on the road.

ROBINSON Having Jeff on the new record is a huge difference maker. We had a hired hand on the last few records, but Jeff is the guy in the band, with his own vision and imagination, and can play a lot of other instruments as well. Tony, our drummer, playing marimba was like, okay, where’d that come from? I’m down! It’s being open to the moment and free. It’s hippie baroque—that’s what I call it.

CASAL Jeff brings so much to the table, in terms of solidifying our lineup, our sound and our confidence. Chris was so excited by the lift that Jeff brought to the band that he wanted to get right back into the studio and capture that feeling.

ROBINSON The benefit with that is that you don’t get too far away from it. Some bands are not cut out for that kind of scheduling, but something that binds the guys in this band is that we’re all lifers: before the show, we’re immersed in music, listening and talking, then we play the show, then afterward we wind down, get back on the bus and it’s always music. We’ve got a turntable on the bus, and Neal, Adam and I are all record-buying swine!

How does this band differ from the Black Crowes?

ROBINSON You can’t compare; these are different times and I’m a different person too. The Black Crowes was a fire that everyone was throwing gasoline on all of the time, because that’s what kept it burning. In this situation, we’ve never had an argument, and everyone plays whatever they want to play. Each of these guys has been in a variety of different bands, too, and this is a musical utopia for all of us. This is all any of us really want—this kind of freedom. If you are not acting in a harmonious way to what is around you, then you are actually in the act of destroying it. We all have great respect for each other, and that is something that cannot be bought.

Let’s talk about the tunes, all of which were written specifically for this record, yes?

ROBINSON Yes. Usually, I have the verses and choruses and Neal will come in with the bridges. For “Blue Star Woman” and “Hark the Herald Hermit Speaks,” I wrote the whole thing. On the “smaller” songs, like “Glow” and “Dog Eat Sun,” they only have two parts to them, and we wanted to keep them simple.

How did the recording process take place?

CASAL Everyone lives at the studio while we are recording, and after you wake up and have your toast and tea, there’s nothing else to do but to make music. By 11 A.M. or so, we’re all on the floor, working. Living there in the same space, you get a three-hour jump on the day.

ROBINSON My house is just down the road. I’d drop my daughter off at school, head up to the studio, make a cup of tea and grab my acoustic, go outside and play, and pick something for us to start with that day. “Behold the Seer” is a perfect example, because I had the intro riff, plus the jam into the verse and that was it. Neal threw in the chorus, and then Adam added some different chords for him to solo over. And that was it, and I love it.

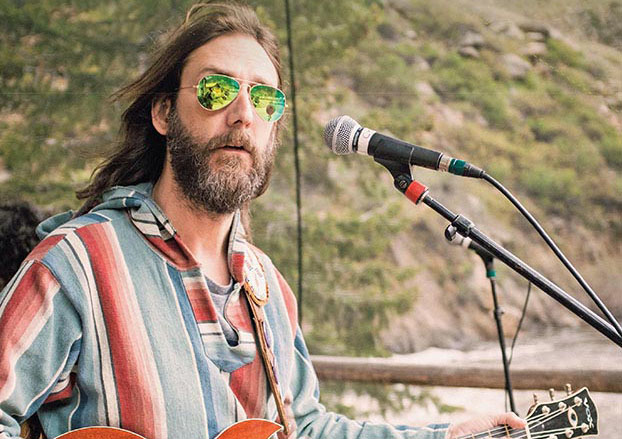

Above: Neal Casal with his Scott Walker Santa Cruz.

Were most to the tracks on each song cut live with everyone playing together? The feeling you get is one of listening to a band play live.

ROBINSON Completely. That’s what is has to be. I’ve heard it said 100 times: rock and roll is dead! They said it when I was a kid and they still say it now, but it’s not true, nor will it ever be true. There are still lots of people going to see Derek [Trucks] play every night, and to them this music is more alive than ever. And the same is true for Jimmy Herring with Widespread Panic and Trey Anastasio. Go to Amoeba Records in San Francisco and you have to wait in line to pay for your fucking shit, so don’t tell me it’s dead!

CASAL Chris has been in a very prolific place, in terms of lyrics and music, over the last two years.

ROBINSON My initial feeling was that it would be “sketchy” and loosey-goosey, but by the end of the very first tune, it had turned into something else. But we did end up with a very acoustic sound on the record, and Neal played so many different acoustic instruments. It was the first time he ever played banjo, on “High Is Not the Top,” with Tony on mandolin. “Glow” was recorded live with Alam Khan, Ali Akbar Khan’s son, on the sarod, whose playing is just phenomenal. I met Alam through Derek.

I’m an obsessive Indian classical music fan, and I thought he would be perfect for this song. It’s my attempt at something that’s a little more “English” and pastoral, like a John Martyn kind of flowing thing. That was one of the most special moments in the studio I have ever experienced.

I’m so glad to have a song like “Good to Know” on this record, that is keyboard driven and kind of lilt-y, a beautifully THC-driven meditation, and then also have “Blonde Light of Day.” All of this music was seen, and created, through the lenses of the guys in the band, so there are many views and many angles to the music. The music should be expressive—the stories we get to tell should take you to new and different places.

Guitar World Associate Editor Andy Aledort is recognized worldwide for his vast contributions to guitar instruction, via his many best-selling instructional DVDs, transcription books and online lessons. Andy is a regular contributor to Guitar World and Truefire, and has toured with Dickey Betts of the Allman Brothers, as well as participating in several Jimi Hendrix Tribute Tours.