Chelsea Wolfe: "Writing while I’m still in the dream world but my eyes are open - that’s always a strange place…"

The doom-folk mage reveals why she took an acoustic turn for new album Birth Of Violence - without ditching the pedals

“I’m always exploring contrasts,” says Chelsea Wolfe, talking to Guitar World about new album Birth Of Violence.

Her sixth full-length marks a departure from all the crackling electric guitar distortion of its predecessor, instead pursuing the warmer realms of atmospheric acoustics, building simple folk ideas into a magnificent oceanic reverie. And yet it still feels every bit as dark and unsettling as the music she’s become famous for…

“There’s a constant dichotomy within me,” muses Chelsea, when asked how she balances the aforementioned contrasts.

A song that the outside world might deem as very dark will still have a little bit of hope or light in there because it exists in all of us… or at least most of us!

“I prefer to explore dark and light at the same time. A song that the outside world might deem as very dark will still have a little bit of hope or light in there because it exists in all of us… or at least most of us! Maybe there are some people that completely dark.

“Generally though, we all have strengths and softness within us. This album was all about balancing those two sides as a woman navigating a world which wants woman to be all things at once. This music is about finding my own definition of that.”

So when exactly did you realize this would be more of an acoustic-based release?

“During [last record] Hiss Spun, which was very heavy, I started to feel mentally and spiritually depleted and exhausted. I couldn’t sleep a lot on the road, so I’d sneak onto the back of the bus, close the door and play my acoustic. It was my way of finding quiet and solace amongst all the chaos of being in constant motion.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“A song like The Mother Road, which opens the album, really encapsulated the spirit of all that. It’s also another name for Route 66, which is one of the main classic thoroughfares through America. You end up on it a lot as a musician and John Steinbeck coined it The Mother Road.

“It felt like a parallel vision of being on the road as well as a woman in today’s world. I had this need for something a bit more quiet and intimate, something that felt a bit more like home.

“Acoustic doesn’t mean just acoustic and vocals to me, it means creating textures with electrics, keyboards and more to create that’s set apart from the heavier rock records I do. Though, of course, there’s an acoustic guitar at the base of everything.”

The acoustics sound very warm - almost as if it’s all fingerpicking or thumb strumming…

“Yeah, I don’t think I used any pick in the end. At one point I thought I might, but I kinda stuck with my fingers and all the strumming was my thumb for sure. That led to getting all that warmth; I wanted to sound rhythmic without being in your face sonically.

I got this Taylor 416 late last year. I guess my way of bonding with it was making this record, so it’s on almost every song

“I got this Taylor 416 late last year. I guess my way of bonding with it was making this record, so it’s on almost every song. There’s also an old classical on one of the songs and a tiny bit of electric guitar here and there…”

And what kind of influences did this approach bring out of you?

“I would say, specifically for this record, it was stuff like Townes Van Zandt, Johnny Cash, Neil Young, Nico - she did an album at Reim’s Cathedral in 1974 where it just sounds like one mic in the middle of the room. It captured the essence of the space, which is important to me.

“It was a lot of old country Loretta Lynn as well as folk like Joni Mitchell, who I grew up on. My mom was always playing her music around the house. There are also little bits of David Bowie in there.

“On Ben [Chisholm]’s production side, there was a little bit of a Marilyn Manson Antichrist Superstar influence that crept in as well. But it’s mainly weirder influences - there’s this song There Stands The Glass by Webb Pierce, and for some reason that had a big influence.”

It must have felt like a return to roots to some extent, considering your family background?

“Yeah, I kinda thought of this album as my space western! My dad was a country musician, so I wanted to marry spacey atmospheric cinematic things into that. I think at the base of everything was the storytelling, which is the essence of folk music.

“There were vocals going through old ribbon mics modeled on the ones from the 1930s, with synthesizers from the 1970s and through this auditory lens of my bandmate Ben’s modern production. He really likes to re-amp things through different amps and pedals.

“It’s fun experimenting with all of that, as well as capturing the atmosphere of my physical surroundings. I’d leave the door open behind to catch some storms raging outside or the fireplace crackling inside. It felt important to create a blanket of atmosphere around the songs.”

So what kind of pedals were you re-amping into?

We used the Eventide Space pedal, a Death By Audio Dream Echo, the Chase Bliss Tonal Recall - that’s such a fun pedal to play with for atmospheric sounds

“On my last two records, there was always one pedal that became the centralized sound for my electric guitar. For Hiss Spun, it was the EarthQuaker Devices Acapulco Gold, which is great because it’s just one giant knob!

“For the new album, it was the Death By Audio Apocalypse, which has the real heavy fuzz. They’re pretty different in that sense, though as soon as I heard them I knew they’d become the sound of my next records and both have stayed onboard since, for sure. We used the Eventide Space pedal, a Death By Audio Dream Echo, the Chase Bliss Tonal Recall - that’s such a fun pedal to play with for atmospheric sounds.

“Beyond that, we used a Prophet synth and this really cool instrument called a Resonant Garden. A lot of the electronic beats came from Ben and I sampling that and then cutting it all up into patterned rhythmic beats. I used this vintage Gibson lapsteel that I picked up at Chicago Music Exchange a couple of years ago… there were a lot of different things for sure! Then, of course, there’s the pedalboard for my voice…”

And what kind of guitar effects did you find work best for your vocals?

I was singing in a lot of spaces, from tiny art galleries with a slap echo to big factories with a lot of reverb. I kind of found my voice that way

“My dad had given me this old digital delay and reverb, so I started singing through those and using a Boss Loop Station. More recently I’ve been playing with heavier reverbs like the EarthQuaker Afterneath.

“I went on a tour in Europe with a harp performer friend of mine - I was singing in a lot of spaces, from tiny art galleries with a slap echo to big factories with a lot of reverb. I kind of found my voice that way. When I got back from that tour, I wanted to recreate those kinds of spaces.”

You’ve generally favored semi-hollowbody electric guitars over the years…

“My Gibson 335s and Gretsch Broadkasters marry really well with these fuzz pedals; they still cut through even if everything’s being totally crushed sonically. I can still hear the tonality of the guitar and some of the high-end, even through the Fender Bassbreaker amp I’ve used for the past four years, which is obviously very bass-heavy.

“The Gibson and Gretsch have been my favorite electrics over the last few years. They gave me this sound I just hadn’t found in solidbody guitars, though I still play a few occasionally.”

Is there a favorite in your collection? Or perhaps a holy grail guitar that you’ve been saving up for…

“Fortunately, one of the ones I have is my absolute favorite. It’s a 1979 Gibson 335, black with a nice crackle finish. My friend Mike Sullivan from Russian Circles helped me find this perfect guitar that’s become one of my absolute number one over the years.

“I’m sure there’s some kind of holy grail out there… I haven’t been to a guitar store in a while. I feel like I have too many guitars already [laughs]. It’s hard to play all of them as it is!”

Do you tend to switch pickups out or do you keep everything original?

I have sleep paralysis and have written a lot about that. It’s the idea of reality and unreality, trying to figure out if you are dreaming or awake

“Generally I switch them out for Seymour Duncans, though that Gibson has the originals kept in. I live in a small town and found this really good guitar guy at the local music shop. He always swaps things out for me and generally it’s the ones that are way louder.”

As for writing, what are the more unusual methods you’ve used to find inspiration?

“I guess one of the weirder and more common places is that space in between sleeping and waking, because I have sleep paralysis and have written a lot about that. It’s the idea of reality and unreality, trying to figure out if you are dreaming or awake.

“Writing while I’m still in the dream world but my eyes are open - that’s always a strange place, but I do it a lot… especially for lyrics. I like the idea of making it feel like you’re in a dream or tripping out.”

That almost revisits what you were saying about dark and light…

“Exactly. Even going back to an old song like Halfsleeper from my first album, it’s a slow-motion portrait of a car accident. It’s pretty gritty in how it talks about body parts spread across asphalt, but it’s still done in a poetic way. Even if the idea is quite hideous and ugly, I try to bring a poetic sense to it.

“I think about it like a movie in my head. What would it look like if it was directed by some great cinematographer, trying to bring beauty into this ugly situation. I think that’s one of the songs that broke me open as an artist and helped me understand my vision as a writer.”

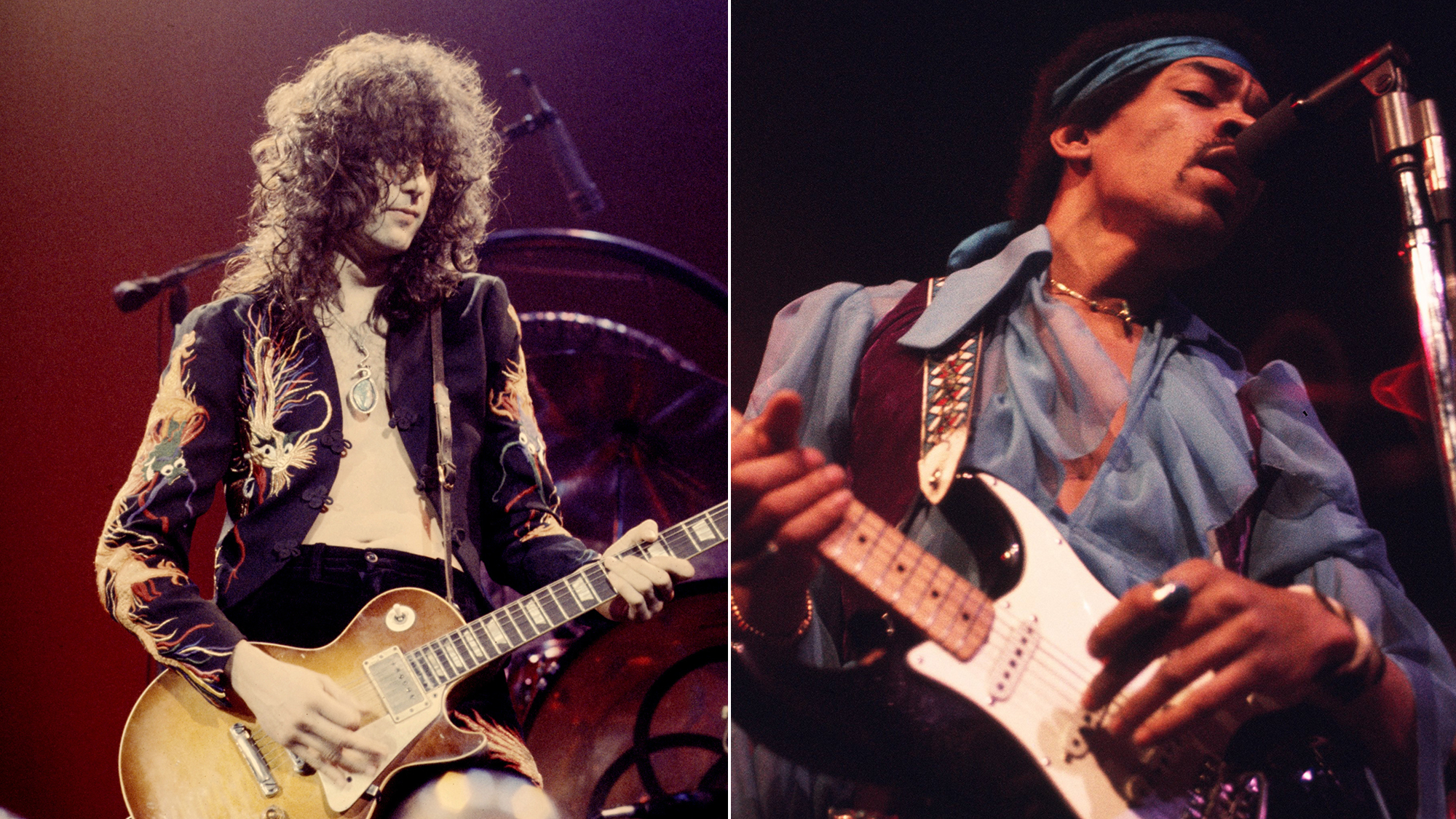

Amit has been writing for titles like Total Guitar, MusicRadar and Guitar World for over a decade and counts Richie Kotzen, Guthrie Govan and Jeff Beck among his primary influences as a guitar player. He's worked for magazines like Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Classic Rock, Prog, Record Collector, Planet Rock, Rhythm and Bass Player, as well as newspapers like Metro and The Independent, interviewing everyone from Ozzy Osbourne and Lemmy to Slash and Jimmy Page, and once even traded solos with a member of Slayer on a track released internationally. As a session guitarist, he's played alongside members of Judas Priest and Uriah Heep in London ensemble Metalworks, as well as handled lead guitars for legends like Glen Matlock (Sex Pistols, The Faces) and Stu Hamm (Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, G3).

Guitar World Discussion: Who is the most underrated guitar player of all time?

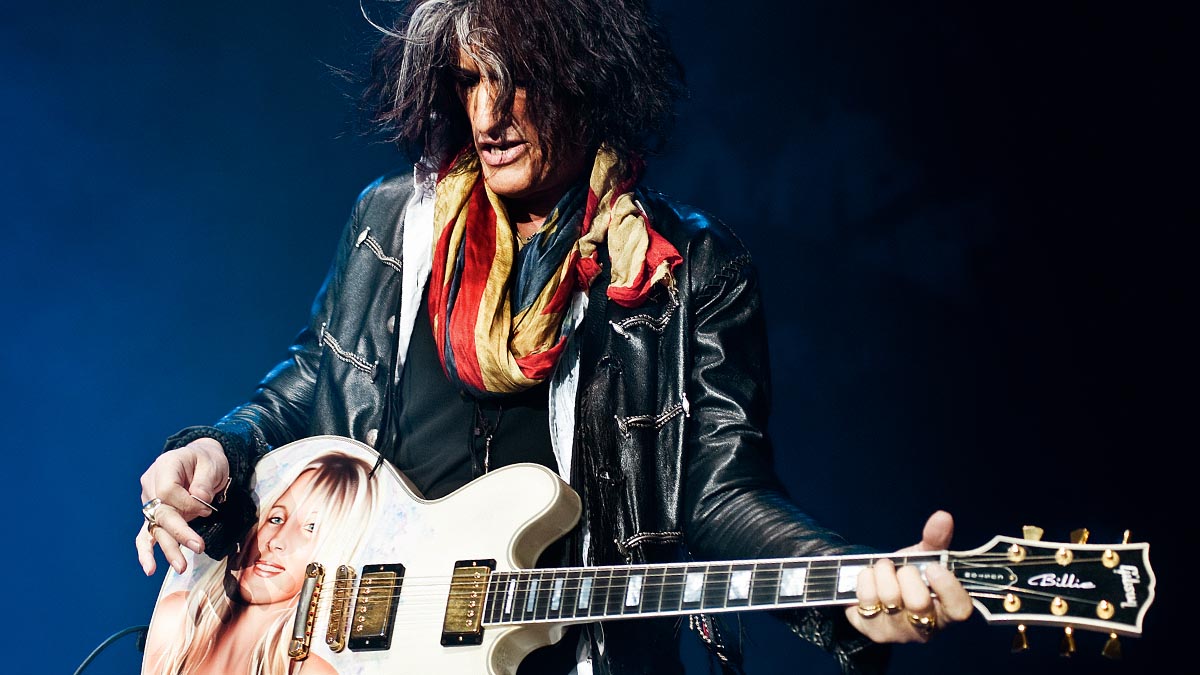

Ozzy Osbourne’s solo band has long been a proving ground for metal’s most outstanding players. From Randy Rhoads to Zakk Wylde, via Brad Gillis and Gus G, here are all the players – and nearly players – in the Osbourne saga