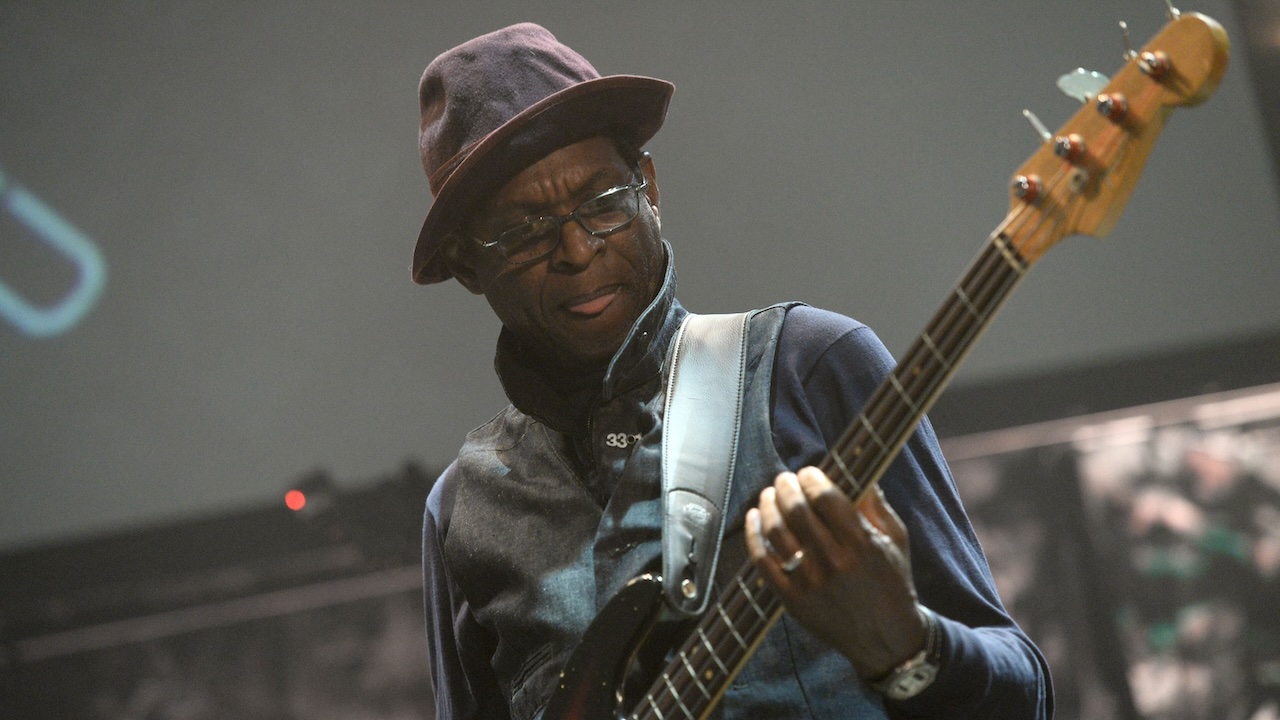

“Was that open-string a mistake or pure brilliance? Who cares? It’s a masterpiece”: Did bass maestro Willie Weeks miss a note on this Donny Hathaway classic?

Willie Weeks is best known for his storied bass solo on Hathaway’s 1972 Live album, but the disc also features what may be his baddest bassline

On the hallowed list of essential bass guitar albums, Donny Hathaway, Live stands shoulder to shoulder with seminal Motown and Beatles sides. Although the incomparable career of bassist Willie Weeks has since taken him to all the major studio cities and concert venues with artists like Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, John Mayer, and Eric Clapton.

The Hathaway experience was so intense for the then-25-year-old Weeks, that he took a year off when he couldn't find a follow-up musical setting as rewarding.

Live is perhaps best known for Weeks's storied solo on Voices Inside (Everything Is Everything) and for a version of Marvin Gaye’s What's Going On favored by club musicians to this day, but the disc also features what may well be his overall baddest bass track: Little Ghetto Boy.

Co-written by Hathaway collaborators Ed Howard and percussionist Earl DeRouen, the song has been covered by Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg, and Norwegian soul singer Noora Noor. Another longtime fan with a deep groove perspective on the track is Austin bassist Roscoe Beck.

“As with a James Jamerson bassline, when you look at a transcription you're dumbfounded,” Beck told Bass Player.

“Willie’s creating a lot of notes and playing figures constantly through the changes. But ignore the dots on the page and what you hear is a part that's swinging and rock solid.”

The song begins in breakdown mode, with minimal percussion and Weeks issuing whole-notes. Bar 4's unison figure ushers in the first verse. With the repeat of the unison figure down an octave at 00:32, the full band is in for the remainder of the verse.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“By bar 14 it's clear that the feel between Willie and Fred White's kick drum is eighth-notes on one and three. Willie also applies chromaticism in the walk-ups, the first nod to his two main bass influences, Jamerson and Ray Brown.”

For the first chorus Weeks moves into classic Jamerson mode, dancing around the root-5th-octave shape.

“White loosens up a bit by abandoning his kick on the downbeat of three in favor of the ‘and’ of three. We also have to marvel at the first of four glorious section-ending two-bar fills, and how bluesy his bass sound is. Willie used his 62 Fender Precision with flat-wounds through an Ampeg SVT.”

Moving to the second verse, Weeks continues with Jamerson-esque syncopations, ghost-notes, and judicious use of open strings (listen to the low E's jump out at 01:11, and dig how he breathes Hathaway's passing chord at 01:22).

“At chorus two White holds the kick drum steady, but Willie is coming into his own groove, almost completely abandoning the original eighth-notes on one and three for a freer, dotted eighth approach. At 01:46, he runs up the neck and gives us hair-raising bass fill number two, coming within two frets of exhausting the P-Bass's upper range.”

Weeks continues his dotted-eighth feel during the keyboard solo. His bass fill at 02:09 is reminiscent not only of his first fill, but of the motif he introduces at the 09:53 mark of his Everything Is Everything solo.

The third and final verse, and subsequent chorus, find Weeks in full swing, adding motion with bold bar-end-ing 16th-note fills, and making an interesting climb at 02:42.

Weeks's third bass fill, at 02:53, is the track's oddest moment: the sudden open G on the ‘and’ of one. Is this a punch from another take? The time shifts ever so slightly, and Live was compiled from shows at the Bitter End in New York and the Troubadour in L.A. Is it an open-string-ringing mistake by Weeks while reaching up the neck? If so, why does Hathaway play a G13 on his keyboard?

“That grabs my ear by the lobes every time. And it seems to get hipper with each listen,” concludes Beck.

“Was it a mistake or pure brilliance? Who cares? This is bass tone to die for! Groove, taste, swing, and innovation: it’s a masterpiece of live bass playing from a musician who remains as vital as ever.”

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.

“I asked him to get me four bass strings because I only had a $29 guitar from Sears”: Bootsy Collins is one of the all-time bass greats, but he started out on guitar. Here’s the sole reason why he switched

“I got that bass for $50 off this coke dealer. I don’t know what Jaco did to it, but he totally messed up the insides!” How Cro-Mags’ Harley Flanagan went from buying a Jaco Pastorius bass on the street to fronting one of hardcore’s most influential bands

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)