“I just remember her playing with a pick. I didn't care how she played, as long as she played the notes right”: Brian Wilson left his mark on the bass world through studio musicians, especially Carol Kaye, who he requested play his basslines note-for-note

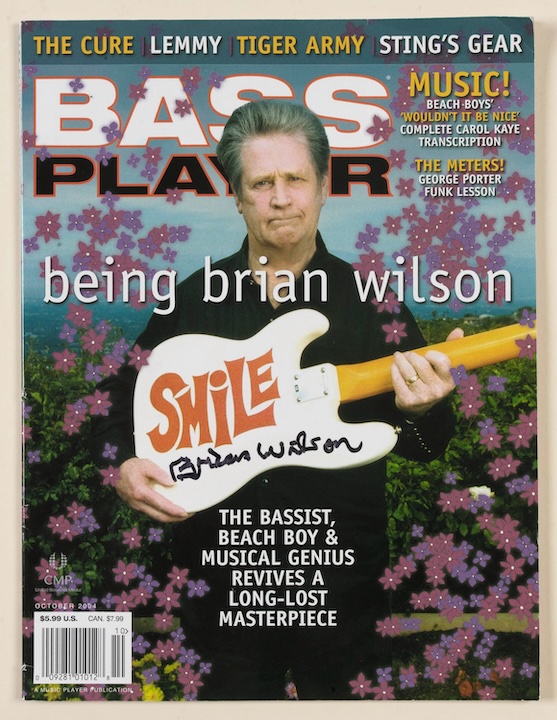

In a rare interview, The Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson reflected on bass playing, studio craft and his 2004 masterpiece, Smile

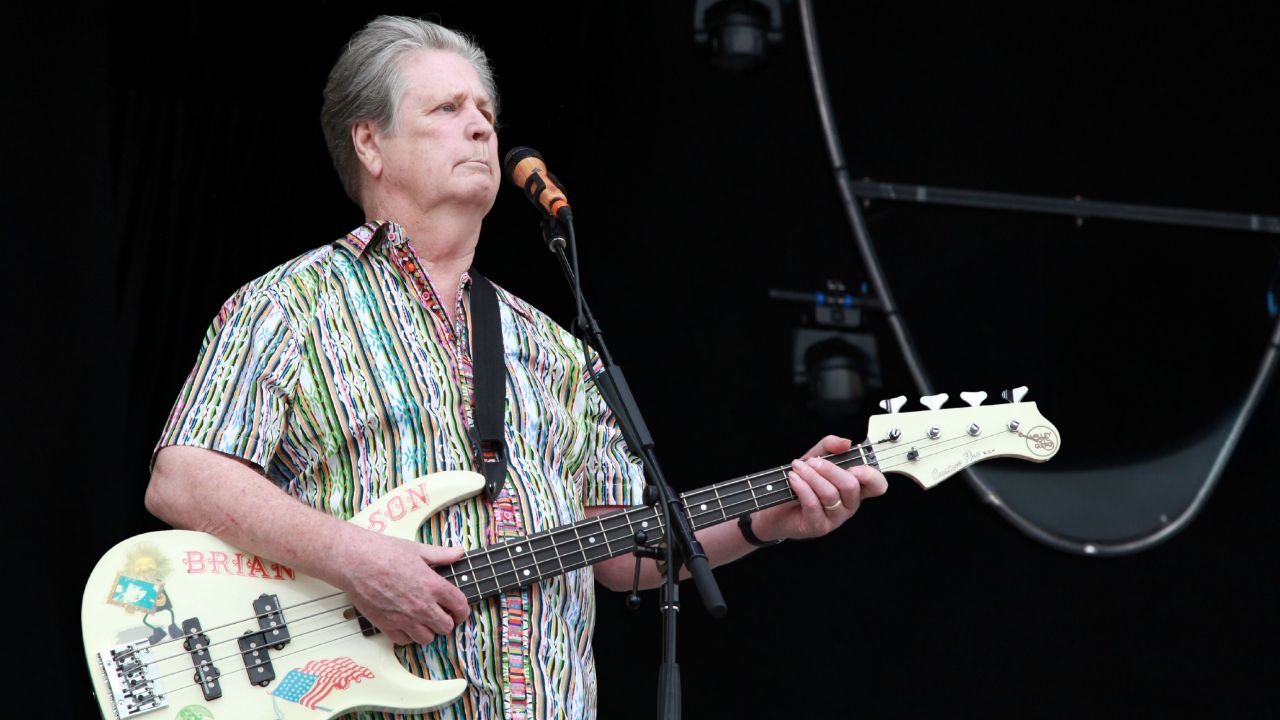

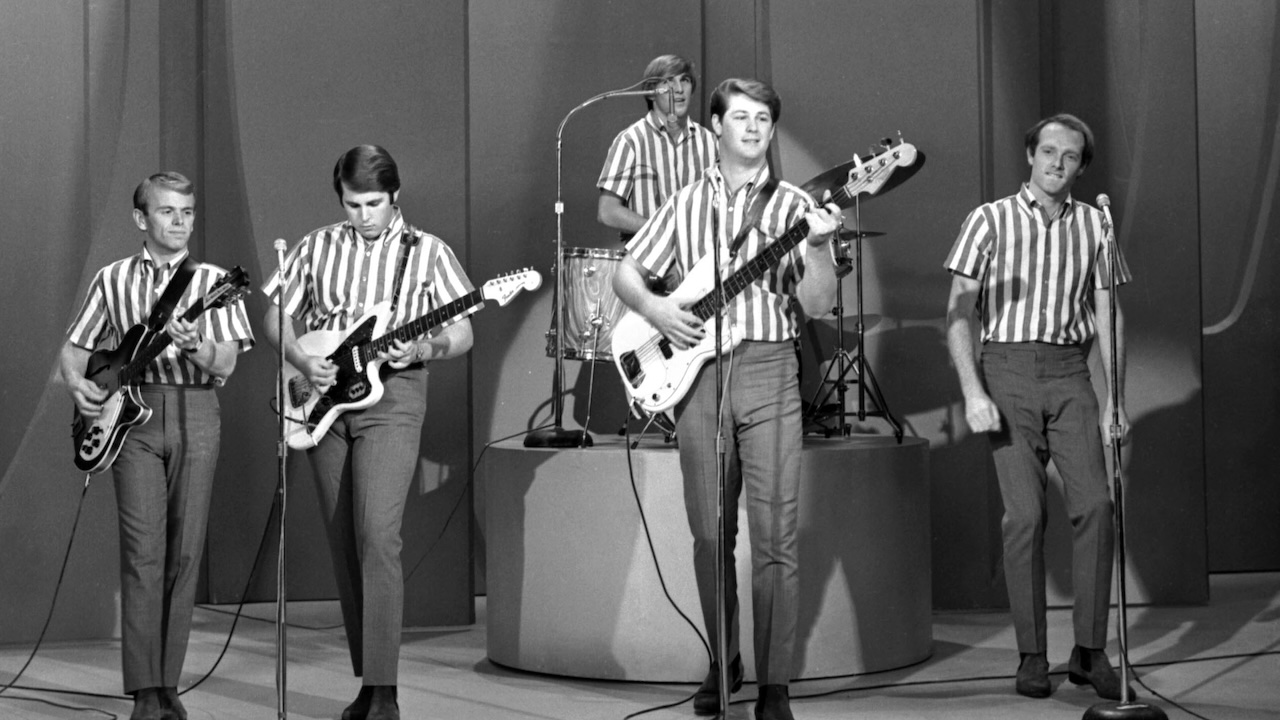

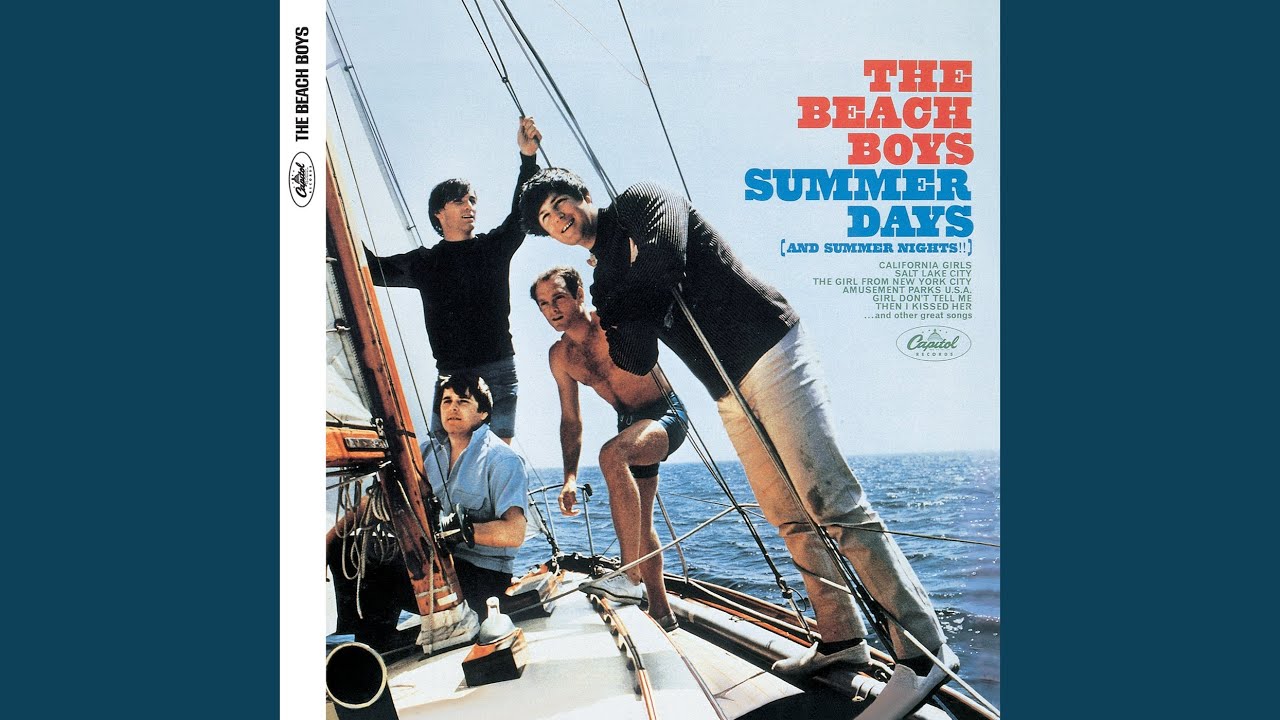

Like Paul McCartney and Sting, Brian Wilson is one of rock ’n’ roll’s most important figures who just happens to play bass. The Beach Boys mastermind and studio savant held down the low-end in the group’s early years – and while he didn’t exactly reinvent the way the instrument is played, later on he left his mark on the bass legacy through session musicians, most notably Carol Kaye.

Back in June 2004 Wilson put out his third solo album, Gettin' In Over My Head, which features guest performances by McCartney, Elton John, and Eric Clapton. Most important by far, though, was the release of Smile, the studio tour-de-force that he began recording in 1966.

Smile was to be the Great American LP, a through-composed follow-up to the Beach Boys' 1966 masterpiece, Pet Sounds – but Wilson scrapped the project shortly before its completion, when personal demons began to catch up with him. Some 60 years later, he decided it was time to dig out the tapes.

"Smile is an attempt to make people happy, the way the Beatles made people happy with their music," Wilson told Bass Player. "It was time for me to put out something really great."

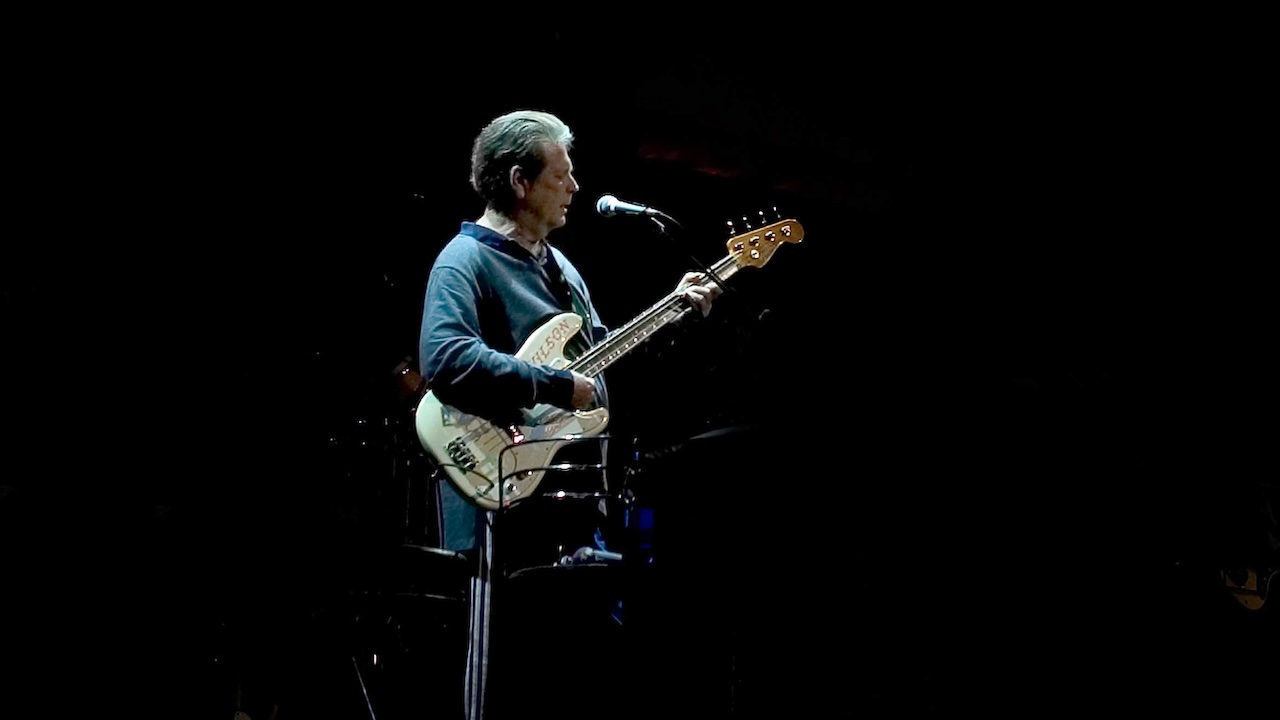

Wilson is one of the most difficult interviews in the music business. Not for the usual reasons, that he's egomaniacal or cruel with journalists; he is neither. Rather, it's basically impossible to form a freewheeling connection with him.

Wilson has endured what no human being should: severe child abuse (which left him deaf in one ear), decades of depression and other mental illnesses, and layer upon layer of unorthodox psychological and pharmacological treatments.

The result is a man who's noticeably uncomfortable simply existing whether he's answering questions, sipping a soda, or as I learned, even working in the studio.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Part of it may be that Wilson simply cannot imagine what it's like to be normal – to not be a musical super-genius. When asked how he comes up with those complex, contrapuntal vocal arrangements, for example, his response is typical: “I just do it. I just do it. Yeah.”

The following interview from the Bass Player archives took place in 2004.

Why did Smile sit in the can for so long?

“I thought the music and Van Dyke Parks' lyrics were too advanced for people. So we waited until 2004 to put it out. It has some really nice backup voices, which my band and I all did together.”

On the recording, are we hearing the musicians from the original sessions, or more recent performances?

“Both. I have my own band now, so we used some of the original tapes and we made some new tapes. We originally wrote and recorded two movements for Smile, and in 2004 we wrote a third movement.”

Are you the sole producer?

“I produced it, but I got some help from Darian Sahanaja.

You're known for your work with session players such as Carol Kaye. When did you first start working with session musicians?

"Around 1965. Carol was my first bassist. Then there was Ray Pohlman, and Lyle Ritz played standup bass. I had the whole crew.”

Do you have any specific memories of your first session with Carol?

“No. I just remember her playing with a pick. She was the main bassist on California Girls, which was one of the first sessions I did with her. She did a great job – she did it real good.”

Did you prefer any one bassist's playing over another's – for example, did you prefer Carol's tone, or the way she attacked the notes?

“I didn't care how she played, as long as she played the notes right. That's all I cared about. But obviously, there's a different tone from a pick player versus a fingerstyle player, for example.”

How much direction did you give Carol?

“I wrote out the notes for her to play, and she played 'em. I said, ‘Please play note-for-note,' and she did exactly what I wanted her to do.

“Sometimes I'd make mistakes on my notes, so I would walk out of the booth and tell the musicians, ‘You're playing this wrong – please play it this way,' and they would make changes to their music.”

Did you ask all of your session musicians to play note-for-note?

“Yes, I was very critical of all the musicians. I'd tell them, ‘Please play what is written.’”

In the studio during the '60s, how hands-on were you with mixing?

“My engineer and I worked the board together on mixing and recording and setting levels. It was a happy time.”

Do you still work the console in the studio?

“No, I let the engineer do most of the balancing now, because he knows what he's doing. I'm a little uncomfortable getting my hands in there.”

That's interesting, considering that you're such a master of the studio environment.

“I just get very nervous in the studio. I really do. I get nervous.”

How do you get over that?

“I don't – until we start playing. I say to myself, ‘You can do it, you can do it.’ But I'm over it by the time we start playing. My bandmates support me very much. When I get real scared, they help me out a lot.”

How did you come to play the bass with the Beach Boys?

“I started out as the band's bass player in 1961, The first time I played a bass guitar was in 1961. My brother Carl taught me how to play it.”

What were your first impressions of it?

“I liked it! I played with a pick, but I didn’t like playing with a pick, so I started playing downward plucks with just my thumb. It was easier for me to play with the thumb.”

What was the first bass you owned?

“It was a white Fender Precision.”

Do you remember anything about the first amp that you had onstage?

“It was a Fender combo amp, about two feet wide. I just plugged straight into it.”

When you first started playing, not surprisingly, your basslines were fairly conventional.

“I was playing tonic notes more than 3rds. As I produced records, I started having bassists play 3rds. Carol Kaye would play 3rds instead of tonics. We'd switch around – a 3rd to a 5th and back to a tonic.”

Did you find yourself getting ideas for basslines by listening to other bassists?

“Motown taught me a little about bass playing, and Phil Spector's records taught me about bass, too.”

How did Phil Spector's records influence you?

“I learned how to put two basses together and mix them into one sound – a standup and a Fender bass. I figured it out by listening – I could hear that they were mixed together.”

When did you first meet Paul McCartney?

“I met him in 1967 in the studio, and I met him again in 1978. He and Linda McCartney came to my house. Then I met him again in 2000, and in 2004 I asked him to come to the studio to record on Gettin' In Over My Head. It was a pretty big thrill. He sang on A Friend Like You and played guitar on the intro.”

You're able to come up with amazing vocal harmonies. How much of that process is internal, and how much requires putting pen to music paper?

“It's about half and half. It starts internal and then becomes external.”

Is it true that you can hear six-part harmonies in your head?

“Oh, yeah – I can do that. After I hear them, I go in and do them. Of course, I can't sing all of the parts at once, so I have to do them one by one. I start with the high note, and then I go all the way down to the bass note.”

Where did you learn about music theory – things like 3rds and octaves?

“An uncle of mine taught me all of that. He just demonstrated on piano what to do, and I did it. I did it real good.”

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“One of the guys said, ‘Joni, there’s this weird bass player in Florida, you’d probably like him’”: How Joni Mitchell formed an unlikely partnership with Jaco Pastorius

“I said, ‘If I could have it my way it would sound like this,’ and I pulled the bass guitar out of the mix”: Why Prince removed the bassline from When Doves Cry

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)